Self-healing hydrogels

Self-healing hydrogels are a specialized type of polymer hydrogel. A hydrogel is a macromolecular polymer gel constructed of a network of crosslinked polymer chains. Hydrogels are synthesized from hydrophilic monomers by either chain or step growth, along with a functional crosslinker to promote network formation. A net-like structure along with void imperfections enhance the hydrogel's ability to absorb large amounts of water via hydrogen bonding. As a result, hydrogels, self-healing alike, develop characteristic firm yet elastic mechanical properties. Self-healing refers to the spontaneous formation of new bonds when old bonds are broken within a material. The structure of the hydrogel along with electrostatic attraction forces drive new bond formation through reconstructive covalent dangling side chain or non-covalent hydrogen bonding. These flesh-like properties have motivated the research and development of self-healing hydrogels in fields such as reconstructive tissue engineering as scaffolding, as well as use in passive and preventive applications.[1]

| Polymer science |

|---|

|

|

Properties

|

|

|

Classification

|

|

Applications

|

Synthesis

A variety of different polymerization methods may be utilized for the synthesis of the polymer chains that make up hydrogels. Their properties depend to an important extent on how these chains are crosslinked.

Crosslinking

Crosslinking is the process of joining two or more polymer chains. Both chemical and physical crosslinking exists. In addition, both natural polymers such as proteins or synthetic polymers with a high affinity for water may be used as starting materials when selecting a hydrogel.[2] Different crosslinking methods can be implemented for the design of a hydrogel. By definition, a crosslinked polymer gel is a macromolecule that solvent will not dissolve. Due to the polymeric domains created by crosslinking in the gel microstructure, hydrogels are not homogenous within the selected solvent system. The following sections summarize the chemical and physical methods by which hydrogels are crosslinked.[2]

Chemical crosslinking

Method | Process |

Radical polymerization | Radical polymerization is a method of chain growth polymerization. Chain-growth polymerization is one of the most common methods for synthesizing hydrogels. Both free-radical polymerization, and more recently, controlled-radical polymerization have been utilized for the preparation of self healing hydrogels. Free radical polymerization consists of initiation, propagation, and termination. After initiation, a free radical active site is generated which adds monomers in a chain link-like fashion. A typical free-radical polymerization showing the formation of a poly(N-isopropyl acrylamide) hydrogel.

Other chain growth methods include anionic and cationic polymerization. Both anionic and cationic methods suffer from extreme sensitivity toward aqueous environments and therefore, are not used in the synthesis of polymeric hydrogels. |

Addition and Condensation Polymerization | Polymer chains may be crosslinked in the presence of water to form a hydrogel. Water occupies voids in the network, giving the hydrogel its characteristic surface properties |

Gamma and Electron Beam Polymerization | High energy electromagnetic irradiation can crosslink water-soluble monomer or polymer chain ends without the addition of a crosslinker. During irradiation, using a gamma or electron beam, aqueous solutions of monomers are polymerized to form a hydrogel. Gamma and electron beam polymerizations parallel the initiation, propagation, and termination model held in free radical polymerization. In this process, hydroxyl radicals are formed and initiate free radical polymerization among the vinyl monomers which propagate in a rapid chain addition fashion.[2] The hydrogel is finally formed once the network reaches the critical gelation point. This process has an advantage over other crosslinking methods since it can be performed at room temperature and in physiological pH without using toxic and hard to remove crosslinking agents |

Physical crosslinking

Method | Process |

Ionic interactions | Using ionic interactions, the process can be performed under mild conditions, at room temperature and physiological pH. It also does not necessarily need the presence of ionic groups in the polymer for the hydrogel to form. The use of metallic ions yield stronger hydrogel.[2] |

Crystallization | |

Stereocomplex Formation | For stereocomplex formation, a hydrogel is formed through crosslinking that is formed between lactic acid oligomers of opposite chirality.[2] |

Hydrophobized polysaccharides | Examples of polysaccharides reported in literature used for the preparation of physically crosslinked hydrogels by hydrophobic modification are chitosan, dextran, pullulan and carboxymethyl curdlan.[2] The hydrophobic interactions results in the polymer to swell and uptake water that forms the hydrogel. |

Protein interaction | Protein engineering has made it possible for engineers to prepare a sequential block copolymers that contains repetition of silk-like and elastine-like blocks called ProLastins.[2] These ProLastins are fluid solutions in water that can undergo a transformation from solution to gel under physiological conditions because of the crystallization of the silk-like domains.[2] |

Hydrogen bonds | Poly Acrylic Acid (PAA) and Poly Methacrylic Acid (PMA) form complexes with Poly Ethylene Glycol (PEG) from the hydrogen bonds between the oxygen of the PEG and carboxylic group of PMA.[2] This interaction allows for the complex to absorb liquids and swell at low pH which transforms the system into a gel. |

Interface chemistry of self-healing hydrogels

Hydrogen bonding

Hydrogen bonding is a strong intermolecular force that forms a special type of dipole-dipole attraction.[4] Hydrogen bonds form when a hydrogen atom bonded to a strongly electronegative atom is around another electronegative atom with a lone pair of electrons.[5] Hydrogen bonds are stronger than normal dipole-dipole interactions and dispersion forces but they remain weaker than covalent and ionic bonds. In hydrogels, structure and stability of water molecules are highly affected by the bonds. The polar groups in the polymer strongly bind water molecules and form hydrogen bonds which also cause hydrophobic effects to occur.[6] These hydrophobic effects can be exploited to design chemically crosslinked hydrogels that exhibit self healing abilities. The hydrophobic effects combined with the hydrophilic effects within the hydrogel structure can be balanced through dangling side chains that mediates the hydrogen bonding that occurs between two separate hydrogel pieces or across a ruptured hydrogel.

Dangling side chain

A dangling side chain is a hydrocarbon chain side chains that branch off of the backbone of the polymer. Attached to the side chain are polar functional groups. The side chains "dangle" across the surface of the hydrogel, allowing it to interact with other functional groups and form new bonds.[7] The ideal side chain would be long and flexible so it could reach across the surface to react, but short enough to minimize steric hindrance and collapse from the hydrophobic effect.[7] The side chains need to keep both the hydrophobic and hydrophilic effects in balance. In a study performed by the University of California San Diego to compare healing ability, hydrogels of varying side chain lengths with similar crosslinking contents were compared and the results showed that healing ability of the hydrogels depends nonmonotonically on the side chain length.[7] With shorter side chain lengths, there is limited reach of the carboxyl group which decreases the mediation of the hydrogen bonds across the interface. As the chain increases in length, the reach of the carboxyl group becomes more flexible and the hydrogen bonds can mediated. However, when a side chain length is too long, the interruption between the interaction of the carboxyl and amide groups that help to mediate the hydrogen bonds. It can also accumulate and collapse the hydrogel and prevent the healing from occurring.

Surfactant effects

Most self-healing hydrogels rely on electrostatic attraction to spontaneously create new bonds.[5][6][7] The electrostatic attraction can be masked using protonation of the polar functional groups. When the pH is raised the polar functional groups become deprotonated, freeing the polar functional group to react. Since the hydrogels rely on electrostatic attraction for self-healing, the process can be affected by electrostatic screening. The effects of a change in salinity can be modeled using the Gouy-Chapman-Stern theory Double Layer .

- : Zeta Potential

- : Salinity of solution

- : Distance between molecules, if the polar functional group is one molecule and an ion in solution is the other.

To calculate the Gouy-Chapmanm potential, the salinity factor must be calculated. The expression given for the salinity factor is as follows:

- : Charge of ion

- : 1.6 * 10^{-19} C

- : Number of ions per cubic meter

- : Dielectric constant of solvent

- : 8.85 * 10^{-12} C^2/(J*m), the permittivity of free space

- : 1.38 * 10^{-23} m^2 kg/(s^2), Boltzmann Constant

- : Temperature in kelvins

These effects become important when considering the application of self-healing hydrogels to the medical field. They will be affected by the pH and salinity of blood.

These effects also come into play during synthesis when trying to add large hydrophobes to a hydrophilic polymer backbone. A research group from the Istanbul Technical University has shown that large hydrophobes can be added by adding an electrolyte in a sufficient amount. During synthesis, the hydrophobes were held in micelles before attaching to the polymer backbone.[8] By increasing the salinity of the solution, the micelles were able to grow and encompass more hydrophobes. If there are more hydrophobes in a micelle, then the solubility of the hydrophobe increases. The increase in the solubility lead to an increase in the formation of hydrogels with large hydrophobes.[8]

Physical properties

Surface properties

Surface tension and energy

The surface tension (γ) of a material is directly related to its intramolecular and intermolecular forces. The stronger the force, the greater the surface tension. This can be modeled by an equation:

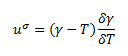

Where ΔvapU is the energy of vaporization, NA is Avogadro's number, and a2 is the surface area per molecule. This equation also implies that the energy of vaporization affects surface tension. It is known that the stronger the force, the higher the energy of vaporization. Surface tension can then be used to calculate surface energy (uσ). An equation describing this property is:

Where T is temperature and the system is at constant pressure and area. Specifically for hydrogels, the free surface energy can be predicted using the Flory–Huggins free energy function for the hydrogels.[9]

For hydrogels, surface tension plays a role in several additional characteristics including swelling ratio and stabilization.

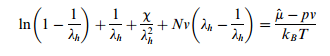

Swelling

Hydrogels have the remarkable ability to swell in water and aqueous solvents. During the process of swelling surface instability can occur. This instability depends on the thickness of the hydrogel layers and the surface tension.[9] A higher surface tension stabilizes the flat surface of the hydrogel, which is the outer-most layer. The swelling ratio of the flat layer can be calculated using the following equation derived from the Flory–Huggins theory of free surface energy in hydrogels:

Where λh is the swelling ratio, μ is the chemical potential, p is pressure, kB is Boltzmann's constant, and χ and Nv are unitless hydrogel constants. As swelling increases, mechanical properties generally suffer.

Surface deformation

The surface deformation of hydrogels is important because it can result in self-induced cracking. Each hydrogel has a characteristic wavelength of instability (λ) that depends on elastocapillary length. This length is calculated by dividing the surface tension (γ) by the elasticity (μ) of the hydrogel. The greater the wavelength of instability, the greater the elastocapillary length of instability, which makes a material more prone to cracking.[10] The characteristic wavelength of instability can be modeled by:

Where H is the thickness of the hydrogel.

Critical solution temperature

Some hydrogels are able to respond to stimuli and their surrounding environments. Examples of these stimuli include light, temperature, pH, and electrical fields. Hydrogels that are temperature sensitive are known as thermogels. Thermo-responsive hydrogels undergo reversible, thermally induced phase transition upon reaching either the upper or lower critical solution temperature. By definition, a crosslinked polymer gel is a macromolecule that cannot dissolve. Due to the polymeric domains created by crosslinking, in the gel microstructure, hydrogels are not homogenous within the solvent system in which they are placed into. Swelling of the network, however, does occur in the presence of a proper solvent. Voids in the microstructure of the gel where crosslinking agent or monomer has aggregated during polymerization can cause solvent to diffuse into or out of the hydrogel. The microstructure of hydrogel therefore are not constant, and imperfections occur where water from outside of the gel can accumulate these voids. This process is temperature dependent, and solvent behavior depends on whether the solvent-gel system has reached, or surpassed, the critical solution temperature (LCST). The LCST defines a boundary between which a gel or polymer chain will separate solvent into one or two phases. The spinodial and binodial regions of a polymer-solvent phase diagram represent the energetic favorability of the hydrogel becoming miscible in solution or separating into two phases.

Applications

Medical Uses

Self-healing hydrogels encompass a wide range of applications. With a high biocompatibility, hydrogels are useful for a number of medical applications. Areas where active research is currently being conducted include:

Tissue Engineering and Regeneration

Polymer scaffolds

Hydrogels are created from crosslinked polymers that are water-insoluble. Polymer hydrogels absorb significant amounts of aqueous solutions, and therefore have a high water content. This high water content makes hydrogel more similar to living body tissues than any other material for tissue regeneration.[12] Additionally, polymer scaffolds using self-healing hydrogels are structurally similar to the extracellular matrices of many of the tissues. Scaffolds act as three-dimensional artificial templates in which the tissue targeted for reconstruction is cultured to grow onto. The high porosity of hydrogels allows for the diffusion of cells during migration, as well as the transfer of nutrients and waste products away from cellular membranes. Scaffolds are subject to harsh processing conditions during tissue culturing.[13] These include mechanical stimulation to promote cellular growth, a process which places stress on the scaffold structure. This stress may lead to localized rupturing of the scaffold which is detrimental to the reconstruction process.[14] In a self-healing hydrogel scaffold, ruptured scaffolds have the ability for localized self-repair of their damaged three-dimensional structure.[15]

Current research is exploring the effectiveness of using various types of hydrogel scaffolds for tissue engineering and regeneration including synthetic hydrogels, biological hydrogels, and biohybrid hydrogels.

In 2019, researchers Biplab Sarkar and Vivek Kumar of the New Jersey Institute of Technology developed a self-assembling peptide hydrogel that has proven successful in increasing blood vessel regrowth and neuron survival in rats affected by Traumatic Brain Injuries (TBI).[16] By adapting the hydrogel to closely resemble brain tissue and injecting it into the injured areas of the brain, the researchers’ studies have shown improved mobility and cognition after only a week of treatment. If trials continued to prove successful, this peptide hydrogel may be approved for human trials and eventual widespread use in the medical community as a treatment for TBIs. This hydrogel also has the potential to be adapted to other forms of tissue in the human body, and promote regeneration and recovery from other injuries.

Synthetic Hydrogels

- Polyethylene glycol (PEG) hydrogels

- Poly (2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate) (PHEMA) hydrogels

Polyethylene glycol(PEG) polymers are synthetic materials that can be crosslinked to form hydrogels. PEG hydrogels are not toxic to the body, do not elicit an immune response, and have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for clinical use. The surfaces of PEG polymers are easily modified with peptide sequences that can attract cells for adhesion and could therefore be used for tissue regeneration.[17]

Poly (2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate) (PHEMA) hydrogels can be combined with rosette nanotubes (RNTs). RNTs can emulate skin structures such as collagen and keratin and self-assemble when injected into the body. This type of hydrogel is being explored for use in skin regeneration and has shown promising results such as fibroblast and keratinocyte proliferation. Both of these cell types are crucial for the production of skin components.[18]

Biological Hydrogels

Biological hydrogels are derived from preexisting components of body tissues such as collagen, hyaluronic acid (HA), or fibrin. Collagen, HA, and fibrin are components that occur naturally in the extracellular matrix of mammals. Collagen is the main structural component in tissues and it already contains cell-signaling domains that can promote cell growth. In order to mechanically enhance collagen into a hydrogel, it must be chemically crosslinked, crosslinked using UV light or temperature, or mixed with other polymers. Collagen hydrogels would be nontoxic and biocompatible.[17]

Hybrid Hydrogels

Hybrid hydrogels combine synthetic and biological materials and take advantage of the best properties of each. Synthetic polymers are easily customizable and can be tailored for specific functions such as biocompatibility. Biological polymers such as peptides also have adventitious properties such as specificity of binding and high affinity for certain cells and molecules. A hybrid of these two polymer types allows for the creation of hydrogels with novel properties. An example of a hybrid hydrogel would include a synthetically created polymer with several peptide domains.[19]

Integrated fiber nanostructures

Peptide-based self-healing hydrogels may be selectively grown onto nanofiber material which can then incorporated into the desired reconstructive tissue target.[20] The hydrogel framework is then chemically modified to promote cell adhesion to the nanofiber peptide scaffold. Because the growth of the extracellular matrix scaffold is pH dependent, the materials selected must be factored for pH response when selecting the scaffolding material.

Drug Delivery

The swelling and bioadhesion of hydrogels can be controlled based on the fluid environment they are introduced to in the body.[12] These properties make them excellent for use as controlled drug delivery devices. Where the hydrogel adheres in the body will be determined by its chemistry and reactions with the surrounding tissues. If introduced by mouth, the hydrogel could adhere to anywhere in the gastrointestinal tract including the mouth, the stomach, the small intestine, or the colon. Adhesion in a specifically targeted region will cause for a localized drug delivery and an increased concentration of the drug taken up by the tissues.[12]

Smart hydrogels in drug delivery

Smart hydrogels are sensitive to stimuli such as changes in temperature or pH. Changes in the environment alter the swelling properties of the hydrogels and can cause them to increase or decrease the release of the drug impregnated into the fibers.[12] An example of this would be hydrogels that release insulin in the presence of high glucose levels in the bloodstream.[21] These glucose sensitive hydrogels are modified with the enzyme glucose oxidase. In the presence of glucose, the glucose oxidase will catalyze a reaction that ends in increased levels of H+. These H+ ions raise the pH of the surrounding environment and could therefore cause a change in a smart hydrogel that would initiate the release of insulin.

Other uses

Although research is currently focusing on the bioengineering aspect of self-healing hydrogels, several non-medical applications do exist, including:

- pH meters

- Sealants for acid leaks

pH Meter

Dangling type side chain self-healing hydrogels are activated by changes in the relative acidity of solution they are in. Depending on user specified application, side chains may be selectively used in self-healing hydrogels as pH indicators. If a specified functional group chain end with a low pKa, such as a carboxylic acid, is subject to a neutral pH conditions, water will deprotonate the acidic chain end, activating the chain ends. Crosslinking or what is known as self-healing will begin, causing two or more separated hydrogels to fuse into one.

Sealant

Research into the use self-healing hydrogels has revealed an effective method for mitigating acid spills through the ability to selectively crosslink under acidic conditions. In a testing done by the University of California San Diego, various surfaces were coated with self healing hydrogels and then mechanically damaged with 300 micrometer wide cracks with the coatings healing the crack within seconds upon exposure of low pH buffers.[7] The hydrogels also can adhere to various plastics due to hydrophobic interactions. Both findings suggest the use of these hydrogels as a sealant for vessels containing corrosive acids. No commercial applications currently exist for implementation of this technology.

Derivatives

Drying of hydrogels under controlled circumstances may yield xerogels and aerogels. A xerogel is a solid that retains significant porosity (15-50%) with a very small pore size (1–10 nm). In an aerogel, the porosity is somewhat higher and the pores are more than an order of magnitude larger, resulting in an ultra-low-density material with a low thermal conductivity and an almost translucent, smoke-like appearance.

See also

- Self healing material

- Biopolymer

- Tissue engineering

- Biosensor

- Supramolecular chemistry

- Gel

- Hydrogel

- Surface chemistry

References

- Talebian, Sepehr; Mehrali, Mehdi; Taebnia, Nayere; Pennisi, Cristian Pablo; Kadumudi, Firoz Babu; Foroughi, Javad; Hasany, Masoud; Nikkhah, Mehdi; Akbari, Mohsen; Orive, Gorka; Dolatshahi‐Pirouz, Alireza (14 June 2019). "Self‐Healing Hydrogels: The Next Paradigm Shift in Tissue Engineering?". Advanced Science. 6 (16): 1801664. doi:10.1002/advs.201801664. PMC 6702654. PMID 31453048.

- Hennink, W.E., van Nostrum, C.F. (2002) Advanced Drug Deliveries Review 54: 13-36.Abstract

- Yokoyama, F.; Masada, I.; Shimamura, K.; Ikawa, T.; Monobe, K. (1986). "Morphology and structure of highly elastic poly(vinyl alcohol) hydrogel prepared by repeated freezing-and-melting". Colloid Polym. Sci. 264 (7): 595–601. doi:10.1007/BF01412597.

- Talebian, Sepehr; Mehrali, Mehdi; Taebnia, Nayere; Pennisi, Cristian Pablo; Kadumudi, Firoz Babu; Foroughi, Javad; Hasany, Masoud; Nikkhah, Mehdi; Akbari, Mohsen; Orive, Gorka; Dolatshahi‐Pirouz, Alireza (14 June 2019). "Self‐Healing Hydrogels: The Next Paradigm Shift in Tissue Engineering?". Advanced Science. 6 (16): 1801664. doi:10.1002/advs.201801664. PMC 6702654. PMID 31453048.

- "Hydrogen Bonding". Chemistry LibreTexts. 2 October 2013.

- Tanaka, Hideki; Tamai, Yoshinori; Nakanishi, Koichiro (1996). "Molecular Dynamics Study of Polymer−Water Interaction in Hydrogels. 2. Hydrogen-Bond Dynamics". Macromolecules. 29 (21): 6761–6769. Bibcode:1996MaMol..29.6761T. doi:10.1021/ma960961r.

- Phadke, Ameya; Zhang, Chao; Arman, Bedri; Hsu, Cheng-Chih; Mashelkar, Raghunath A.; Lele, Ashish K.; Tauber, Michael J.; Arya, Gaurav; Varghese, Shyni (29 February 2012). "Rapid self-healing hydrogels". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. doi:10.1073/pnas.1201122109.

- Tuncaboylu, Deniz C.; Melahat Sahin; Aslihan Argun; Wilhelm Oppermann; Oguz Okay (6 February 2012). "Dynamics and Large Strain Behavior of Self-Healing Hydrogels with and without Surfactants". Macromolecules. 45 (4): 1991–2000. Bibcode:2012MaMol..45.1991T. doi:10.1021/ma202672y.

- Kang, Min K.; Huang, Rui (2010). "Effect of surface tension on swell-induced surface instability of substrate-confined hydrogel layers". Soft Matter. 6 (22): 5736–5742. Bibcode:2010SMat....6.5736K. doi:10.1039/c0sm00335b.

- Aditi Chakrabarti and Manoj K. Chaudhury (2013). "Direct Measurement of the Surface Tension of a Soft Elastic Hydrogel: Exploration of Elastocapillary Instability in Adhesion". Langmuir. 29 (23): 6926–6935. arXiv:1401.7215. doi:10.1021/la401115j. PMID 23659361.

- Gibas, Iwona; Janik, Helena (7 October 2010). "REVIEW: SYNTHETIC POLYMER HYDROGELS FOR BIOMEDICAL APPLICATIONS" (PDF). Chemistry and Chemical Technologies. 4 (4): 297–304.

- Vadithya, Ashok (2012). "As A Review on Hydrogels as Drug Delivery in the Pharmaceutical Field". International Journal of Pharmaceutical and Chemical Sciences.

- Schmedlen, Rachael H; Kristyn Masters (8 November 2002). "Photocrosslinkable polyvinyl alcohol hydrogels that can be modified with cell adhesion peptides for use in tissue engineering". Biomaterials. 23 (22): 4325–4332. doi:10.1016/s0142-9612(02)00177-1. PMID 12219822.

- Stosich, Michael H; Eduardo Moioli (24 October 2009). "Bioengineering strategies to generate vascularized soft tissue grafts with sustained shape". Methods. 47 (2): 116–121. doi:10.1016/j.ymeth.2008.10.013. PMC 4035046. PMID 18952179.

- Brochu, Alic H; Stephen Craig (9 December 2010). "Self-healing biomaterials". Biomaterials. 96 (2): 492–506. doi:10.1002/jbm.a.32987. PMC 4547467. PMID 21171168.

- "Peptide hydrogels could help heal traumatic brain injuries". ScienceDaily.

- Peppas, Nicholas (2006). "Hydrogels in Biology and Medicine: From Molecular Principles to Bionanotechnology". Advanced Materials. 18 (11): 1345–1360. doi:10.1002/adma.200501612.

- Chaudhury, Koel; Kandasamy, Jayaprakash; Kumar H S, Vishu; RoyChoudhury, Sourav (September 2014). "Regenerative nanomedicine: current perspectives and future directions". International Journal of Nanomedicine: 4153. doi:10.2147/IJN.S45332. PMC 4159316. PMID 25214780.

- Kopeček, Jindřich; Yang, Jiyuan (March 2009). "Peptide-directed self-assembly of hydrogels". Acta Biomaterialia. 5 (3): 805–816. doi:10.1016/j.actbio.2008.10.001. PMC 2677391. PMID 18952513.

- Zhou, Mi H; Andrew Smith (6 May 2009). "Self-assembled peptide-based hydrogels as scaffolds for anchorage-dependent cells". Biomaterials. 30 (13): 2523–2530. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.01.010. PMID 19201459.

- Roy, Ipsita (December 2003). "Smart Polymeric Materials: Emerging Biochemical Applications". Chemistry and Biology. 10 (12): 1161–1171. doi:10.1016/j.chembiol.2003.12.004. PMID 14700624.

Further reading

- Ma, Xiaotang; Agas, Agnieszka; Siddiqui, Zain; Kim, KaKyung; Iglesias-Montoro, Patricia; Kalluru, Jagathi; Kumar, Vivek; Haorah, James (March 2020). "Angiogenic peptide hydrogels for treatment of traumatic brain injury". Bioactive Materials. 5 (1): 124–132. doi:10.1016/j.bioactmat.2020.01.005.