Sardis

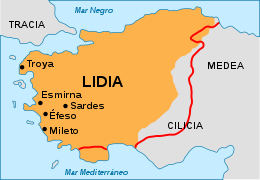

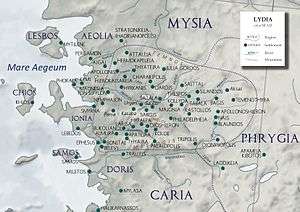

Sardis (/ˈsɑːrdɪs/) or Sardes (/ˈsɑːrdiːz/; Lydian: 𐤮𐤱𐤠𐤭𐤣 Sfard; Ancient Greek: Σάρδεις Sardeis; Old Persian: Sparda; Biblical Hebrew: ספרד Sfarad) was an ancient city at the location of modern Sart (Sartmahmut before 19 October 2005), near Salihli, in Turkey's Manisa Province. Sardis was the capital of the ancient kingdom of Lydia,[1] one of the important cities of the Persian Empire, the seat of a Seleucid Satrap, the seat of a proconsul under the Roman Empire, and the metropolis of the province Lydia in later Roman and Byzantine times. As one of the seven churches of Asia, it was addressed by John, the author of the Book of Revelation in the New Testament,[2] in terms which seem to imply that its church members did not finish what they started, that they were about image and not substance.[3] Its importance was due first to its military strength, secondly to its situation on an important highway leading from the interior to the Aegean coast, and thirdly to its commanding the wide and fertile plain of the Hermus.

Σάρδεις (in Greek) | |

.jpg) The Greek gymnasium of Sardis | |

Shown within Turkey | |

| Alternative name | Sardes |

|---|---|

| Location | Sart, Manisa Province, Turkey |

| Region | Lydia |

| Coordinates | 38°29′18″N 28°02′25″E |

| Type | Settlement |

| History | |

| Abandoned | Around 1402 AD |

| Cultures | Greek, Lydian, Persian, Roman |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 1910–1914, 1922, 1958–present |

| Archaeologists | Howard Crosby Butler, G.M.A. Hanfmann, Crawford H. Greenewalt, jr., Nicholas Cahill |

| Condition | Ruined |

| Ownership | Public |

| Public access | Yes |

| Website | Archaeological Exploration of Sardis |

Geography

Sardis was situated in the middle of Hermus valley, at the foot of Mount Tmolus, a steep and lofty spur which formed the citadel. It was about 4 kilometres (2.5 mi) south of the Hermus. Today, the site is located by the present day village of Sart, near Salihli in the Manisa province of Turkey, close to the Ankara - İzmir highway (approximately 72 kilometres (45 mi) from İzmir). The part of remains including the bath-gymnasium complex, synagogue and Byzantine shops is open to visitors year-round.

History

.jpg)

Foundation stories

The Greek historian and father of history, Herodotus, notes that the city was founded by the sons of Hercules, the Heraclides. According to Herodotus, the Heraclides ruled for five hundred and five years beginning with Agron, 1220 BC, and ending with Candaules, 716 BC. They were followed by the Mermnades, which began with Gyges, 716 BC, and ended with Croesus, 546 BC.[4] The earliest reference to Sardis is in The Persians of Aeschylus (472 BC); in the Iliad, the name “Hyde” seems to be given to the city of the Maeonian (i.e. Lydian) chiefs and in later times Hyde was said to be the older name of Sardis, or the name of its citadel.

It is, however, more probable that Sardis was not the original capital of the Maeonians, but that it became so amid the changes which produced the powerful Lydian empire of the 8th century BC.

Target of conquest

The city was captured by the Cimmerians in the 7th century BC, by the Persians in the 6th, by the Athenians in the 5th, and by Antiochus III the Great at the end of the 3rd century BC.

In the Persian era, Sardis was conquered by Cyrus the Great and formed the end station for the Persian Royal Road which began in Persepolis, capital of Persia. Sardis was the site of the most important Persian satrapy.[5]

During the Ionian Revolt, the Athenians burnt down the city. Sardis remained under Persian domination until it surrendered to Alexander the Great in 334 BC.

Reliable gold coins

The early Lydian kingdom was very advanced in the industrial arts and Sardis was the chief seat of its manufactures. The most important of these trades was the manufacture and dyeing of delicate woolen stuffs and carpets. The stream Pactolus which flowed through the market-place "carried golden sands" in early antiquity, which was in reality gold dust out of Mount Tmolus. It was during the reign of King Croesus that the metallurgists of Sardis discovered the secret of separating gold from silver, thereby producing both metals of a purity never known before.[6]

This was an economic revolution, for while gold nuggets panned or mined were used as currency, their purity was always suspect and a hindrance to trade. Such nuggets or coinage were naturally occurring alloys of gold and silver known as electrum and one could never know how much of it was gold and how much was silver. Sardis now could mint nearly pure silver and gold coins, the value of which could be – and was – trusted throughout the known world. This revolution made Sardis rich and Croesus' name synonymous with wealth itself. For this reason, Sardis is famed in history as the place where modern currency was invented.

Desolation in 17 AD earthquake

%2C_Turkey_(31358519643).jpg)

.jpg)

Disaster came to the great city under the reign of the emperor Tiberius, when in 17 AD, Sardis was destroyed by an earthquake, but it was rebuilt with the help of ten million sesterces from the Emperor and exempted from paying taxes for five years.[7] It was one of the great cities of western Asia Minor until the later Byzantine period.

Later, trade and the organization of commerce continued to be sources of great wealth. After Constantinople became the capital of the East, a new road system grew up connecting the provinces with the capital. Sardis then lay rather apart from the great lines of communication and lost some of its importance. It still, however, retained its titular supremacy and continued to be the seat of the metropolitan bishop of the province of Lydia, formed in 295 AD. It was enumerated as third, after Ephesus and Smyrna, in the list of cities of the Thracesion thema given by Constantine Porphyrogenitus in the 10th century. However, over the next four centuries it was in the shadow of the provinces of Magnesia-upon-Sipylum and Philadelphia, which retained their importance in the region.

Decline and fall in the second millennium, AD

After 1071, the Hermus valley began to suffer from the inroads of the Seljuk Turks but the Byzantine general John Doukas reconquered the city in 1097. The successes of the general Philokales in 1118 relieved the district from later Turkish pressure and the ability of the Comneni dynasty together with the gradual decay of the Seljuk Sultanate of Rum meant that it remained under Byzantine dominion. When Constantinople was taken by the Venetians and Franks in 1204 Sardis came under the rule of the Byzantine Empire of Nicea.

However once the Byzantines retook Constantinople in 1261, Sardis with the entire Asia Minor was neglected and the region eventually fell under the control of Ghazi (Ghazw) emirs. The Cayster valleys and a fort on the citadel of Sardis was handed over to them by treaty in 1306. The city continued its decline until its capture (and probable destruction) by the Turco-Mongol warlord Timur in 1402.

Archaeological expeditions

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Current laws governing archaeological expeditions in Turkey ensure that all artifacts remain in Turkey. Some of the important finds from the site of Sardis are housed in the Archaeological Museum of Manisa, including Late Roman mosaics and sculpture, a helmet from the mid-6th century BCE, and pottery from various periods.

Roman antiquities

By the 19th century, Sardis was in ruins, showing construction chiefly of the Roman period. Early excavators included the British explorer George Dennis, who uncovered an enormous marble head of Faustina the Elder, wife of the Roman Emperor Antoninus Pius. Found in the precinct of the Temple of Artemis, it probably formed part of a pair of colossal statues devoted to the Imperial couple. The 1.76 metre high head is now kept at the British Museum.[8]

The first large-scale archaeological expedition in Sardis was directed by a Princeton University team led by Howard Crosby Butler between years 1910–1914, unearthing a temple to Artemis, and more than a thousand Lydian tombs. The excavation campaign was halted by World War I, followed by the Turkish War of Independence, though it briefly resumed in 1922. Some surviving artifacts from the Butler excavation were added to the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

Sardis synagogue

The Hebrew place-name Sepharad may have meant Sardis.

A new expedition known as the Archaeological Exploration of Sardis was founded in 1958 by G.M.A. Hanfmann, professor in the Department of Fine Arts at Harvard University, and by Henry Detweiler, dean of the Architecture School at Cornell University. Hanfmann excavated widely in the city and the region, excavating and restoring the major Roman bath-gymnasium complex, the synagogue, late Roman houses and shops, a Lydian industrial area for processing electrum into pure gold and silver, Lydian occupation areas, and tumulus tombs at Bin Tepe.[9]

From 1976 until 2007, the excavation was directed by Crawford H. Greenewalt, Jr., professor in the Department of Classics at the University of California, Berkeley.[10] Since 2008, the excavation has been under the directorship of Nicholas Cahill, professor at the University of Wisconsin–Madison.[11]

Since 1958, both Harvard and Cornell Universities have sponsored annual archeological expeditions to Sardis. These excavations unearthed perhaps the most impressive synagogue in the western diaspora yet discovered from antiquity, yielding over eighty Greek and seven Hebrew inscriptions as well as numerous mosaic floors. (For evidence in the east, see Dura Europos in Syria.) The discovery of the Sardis synagogue has reversed previous assumptions about Judaism in the later Roman empire. Along with the discovery of the godfearers / theosebeis inscription from Aphrodisias, it provides indisputable evidence for the continued presence of Jewish communities in Asia Minor and their integration into general Roman life at a time when many scholars previously assumed that Christianity had eclipsed Judaism.

The synagogue was a section of a large bath-gymnasium complex, that was in use for about 450–500 years. In the late 4th or 5th century, part of the bath-gymnasium complex was changed into a synagogue.

See also

- Cities of the ancient Near East

- List of synagogues in Turkey

References

- Rhodes, P.J. A History of the Classical Greek World 478-323 BC. 2nd edition. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2010, p. 6.

- Revelation 3:1-6

- revelation 3:2

- Cockayne, O. (1844). "On the Lydian Dynasty which preceded the Mermnadæ". Proceedings of the Philological Society. 1 (24): 274.

- Raditsa 1983, p. 105.

- Ramage, A.; Craddock, P. (2001). "King Croesus' Gold: Excavations at Sardis and the history of gold refining". Archaeological Exploration of Sardis.

- Tacitus, The Annals 2.47

- "Research collection online". British Museum.

- Hanfmann, George M.A., Et al. 1983. Sardis from Prehistoric to Roman Times: Results of the Archaeological Exploration of Sardis 1958–1975, Harvard University Press.

- Cahill, Nicholas D., ed. 2008. "Love for Lydia. A Sardis Anniversary Volume Presented to Crawford H. Greenewalt, jr.", Archaeological Exploration of Sardis.

- "Archaeological Exploration of Sardis, Harvard Art Museums". Retrieved January 9, 2013.

Sources

- Raditsa, Leo (1983). "Iranians in Asia Minor". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). The Cambridge History of Iran, Vol. 3 (1): The Seleucid, Parthian and Sasanian periods. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1139054942.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Elderkin, G. W. "The Name of Sardis." Classical Philology 35, no. 1 (1940): 54-56. Accessed July 11, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/264594.

- Hanfmann, George M. A. "EXCAVATIONS AT SARDIS." Scientific American 204, no. 6 (1961): 124-38. Accessed July 11, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/24937494.

- HANFMANN, GEORGE M. A., and A. H. DETWEILER. "Sardis Through the Ages." Archaeology 19, no. 2 (1966): 90-97. Accessed July 11, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/41670460.

- George M. A. Hanfmann. "Archeological Explorations of Sardis." Bulletin of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences 27, no. 2 (1973): 13-26. Accessed July 11, 2020. doi:10.2307/3823622.

- Hanfmann, George M.A., Et al. 1983. Sardis from Prehistoric to Roman Times: Results of the Archaeological Exploration of Sardis 1958–1975, Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-78925-3

- HANFMANN, G. M. A. "The Sacrilege Inscription: The Ethnic, Linguistic, Social and Religious Situation at Sardis at the End of the Persian Era." Bulletin of the Asia Institute, New Series, 1 (1987): 1-8. Accessed July 11, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/24048256.

- Greenewalt, Crawford H., Marcus L. Rautman, and Nicholas D. Cahill. "The Sardis Campaign of 1985." Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research. Supplementary Studies, no. 25 (1988): 55-92. Accessed July 11, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/20066668.

- Ramage, Andrew. "EARLY IRON AGE SARDIS AND ITS NEIGHBOURS." In Anatolian Iron Ages 3: The Proceedings of the Third Anatolian Iron Ages Colloquium Held at Van, 6-12 August 1990, edited by Çilingiroğlu A. and French D.H., 163-72. London: British Institute at Ankara, 1994. Accessed July 11, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/10.18866/j.ctt1pc5gxc.26.

- Ramage, Nancy H. "PACTOLUS CLIFF: AN IRON AGE SITE AT SARDIS AND ITS POTTERY." In Anatolian Iron Ages 3: The Proceedings of the Third Anatolian Iron Ages Colloquium Held at Van, 6-12 August 1990, edited by Çilingiroğlu A. and French D.H., 173-84. London: British Institute at Ankara, 1994. Accessed July 11, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/10.18866/j.ctt1pc5gxc.27.

- Greenwalt, Crawford H. "Sardis in the Age of Xenophon". In: Pallas, 43/1995. Dans les pas des dix-mille, sous la direction de Pierre Briant. pp. 125-145. [DOI: https://doi.org/10.3406/palla.1995.1367]; www.persee.fr/doc/palla_0031-0387_1995_num_43_1_1367

- Gadbery, Laura M. "Archaeological Exploration of Sardis." Harvard University Art Museums Bulletin 4, no. 3 (1996): 49-53. Accessed July 11, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/4301536.

- Mitten, David Gordon. "Lydian Sardis and the Region of Colchis: Three Aspects". In: Sur les traces des Argonautes. Actes du 6e symposium de Vani (Colchide), 22-29 septembre 1990. Besançon : Université de Franche-Comté, 1996. pp. 129-140. (Annales littéraires de l'Université de Besançon, 613) [www.persee.fr/doc/ista_0000-0000_1996_act_613_1_1486]

- Cahill, Nicholas D., ed. 2008. "Love for Lydia. A Sardis Anniversary Volume Presented to Crawford H. Greenewalt, jr.", Archaeological Exploration of Sardis. ISBN 9780674031951.

- Payne, Annick, and Jorit Wintjes. "Sardis and the Archaeology of Lydia." In Lords of Asia Minor: An Introduction to the Lydians, 47-62. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, 2016. Accessed July 11, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctvc5pfx2.7.

- Berlin, Andrea M., and Paul J. Kosmin, eds. Spear-Won Land: Sardis from the King's Peace to the Peace of Apamea. Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press, 2019. Accessed July 11, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctvj7wnr9.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sardis. |

- The Archaeological Exploration of Sardis

- The Archaeological Exploration of Sardis, of the Harvard University Art Museums

- The Search for Sardis, history of the archaeological excavations in Sardis, in the Harvard Magazine

- Sardis, at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

- Sardis Turkey, a comprehensive photographic tour of the site

- The Princeton Encyclopedia of Classical Sites - Sardis

- Livius.org: Sardes - pictures