Sandgate Castle

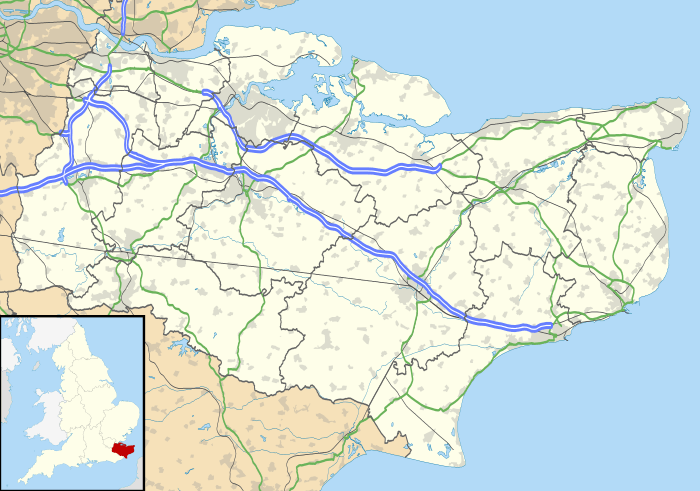

Sandgate Castle is an artillery fort originally constructed by Henry VIII in Sandgate in Kent, between 1539 and 1540. It formed part of the King's Device programme to protect England against invasion from France and the Holy Roman Empire, and defended vulnerable point along the coast. It comprised a central stone keep, with three towers and a gatehouse. It could hold four tiers of artillery, and was fitted with a total of 142 firing points for cannon and handguns.

| Sandgate Castle | |

|---|---|

| Sandgate, England | |

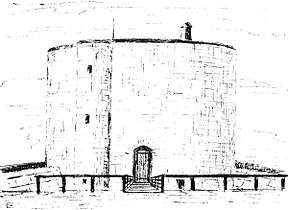

Castle seen from the beach | |

Sandgate Castle | |

| Coordinates | 51.073444°N 1.148889°E |

| Type | Device Fort |

| Site information | |

| Owner | Private |

| Open to the public | No |

| Condition | Restored |

| Site history | |

| Built | 1539–40 |

| Events | English Civil War Napoleonic Wars |

Sandgate was taken by Parliament in 1642 at the start of the first English Civil War, and was seized by Royalist rebels in the second civil war of 1648. The castle was extensively redesigned between 1805 and 1808 during the Napoleonic Wars. The height of the castle was significantly reduced and the keep was turned into a Martello tower; when the work was completed, it was armed with ten 24-pounder (11 kg) guns and could hold a garrison of 40 men.

The castle had begun to suffer damage from the sea by the early 17th century, and by the middle of the 19th century, the receding coastline had reached the edge of the castle walls. The high costs of repair contributed to the government's decision to sell the site off in 1888. It was initially bought by a railway company and then passed into private ownership.

Coastal erosion continued and by the 1950s, the southern part of the castle had been destroyed by the sea. The remaining castle was restored between 1975 and 1979 by Peter and Barbara McGregor, who turned the keep into a private residence. In the 21st century, Sandgate remains in private ownership, and is protected under UK law as a grade I listed building.

History

16th century

Sandgate Castle was built as a consequence of international tensions between England, France and the Holy Roman Empire in the final years of the reign of King Henry VIII. Traditionally the Crown had left coastal defences to the local lords and communities, only taking a modest role in building and maintaining fortifications, and while France and the Empire remained in conflict with one another, maritime raids were common but an actual invasion of England seemed unlikely.[1] Modest defences, based around simple blockhouses and towers, existed in the south-west and along the Sussex coast, with a few more impressive works in the north of England, but in general the fortifications were very limited in scale.[2]

In 1533, Henry broke with Pope Paul III in order to annul the long-standing marriage to his wife, Catherine of Aragon and remarry.[3] Catherine was the aunt of Charles V, the Holy Roman Emperor, and he took the annulment as a personal insult.[4] This resulted in France and the Empire declaring an alliance against Henry in 1538, and the Pope encouraging the two countries to attack England.[5] An invasion of England appeared certain.[6] In response, Henry issued an order, called a "device", in 1539, giving instructions for the "defence of the realm in time of invasion" and the construction of forts along the English coastline.[7]

Sandgate was intended to defend a vulnerable point along the Kent cliffs, just west of Folkestone, where an enemy force could potentially land and make their way easily further inland.[8] Sandgate's construction was supervised by the Moravian engineer Stefan von Haschenperg, and Thomas Cockys and Richard Keys acted as commissioners for the project.[9] In the initial stages of the work in 1539, a team of 237 men were employed, with masons, quarrymen, limeburners and wood fellers preparing the site; the masons were drawn from as far away as Somerset and Gloucestershire.[10] By the summer, over 500 were at work, including labourers, bricklayers, carpenters and sawyers.[11] After a pause during the winter months, work picked up again in the summer of the next year, with 630 working on the castle that July.[11]

The castle's foundations rested on the underlying shingle of the beach.[12] The walls were made from Kentish ragstone, mostly roughly laid, with some work using finer ashlar, with Caen stone used in the detailing.[12] Most of the ragstone was collected from the local beaches, where there were suitable outcrops to the west and east of the site.[13] 459 tons of Caen stone was recycled from the priories of Christ Church and Horton, which had recently been dissolved by Henry.[13] In total, 147,000 bricks were used, produced at 13 different brickyards, and 44,000 tiles, mostly manufactured in Wye, along with 1,829 loads of lime, 110 tons of coal and 979 tons of timber.[14] The total cost of the project came to £5,584.[15][lower-alpha 1]

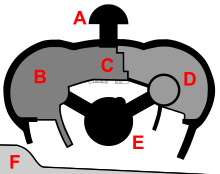

At the centre of the new castle was a circular keep, with three ovoid towers and bastions around it on the northwest, northeast and south sides, and a gatehouse to the north.[17] These were surrounded by two curtain walls, forming a triangular inner and outer ward.[18] Covered stone passageways, three storeys high, linked the towers, the keep and the gatehouse.[19] The outer ward was grassed over, with a stone cesspool by the side of the north-east tower, linked by sewers to the inside of the castle.[20] The castle was entered through a doorway in the rear of the gatehouse, originally called the "Half Moon", linked by a stairway in the covered passageway to the keep.[21] There were four tiers of guns in the finished castle, from the ground level up to the roof of the keep, and a total of 142 firing points for cannon and handguns; their design closely resembling those at nearby Walmer and Deal castles.[22]

Sandgate was completed by the autumn of 1540; Henry may have come to the castle when he was visiting Folkestone in May 1542.[23] Elizabeth I visited the fortification in 1573, and also used it to imprison the courtier Thomas Keyes for a period, after he married Lady Mary Grey against the Queen's wishes.[24] In 1593, the castle was reported to be equipped with seven artillery pieces - one culverin, two demi-culverins, three sakers and one minion - along with muskets, bows and arrows.[25]

17th–18th centuries

In 1609, the garrison comprised a captain and his lieutenant, five soldiers, two porters and ten gunners.[26] The mortar used in the castle was particularly poor, and had begun to seriously decay by 1616.[27] A survey that year showed the castle to be substantially dilapidated, with the cost of the proposed repairs estimated at £260, and noted that a 100 feet (30 m) gun platform for ten weapons had been built along the southern walls to replace the original southern battery.[28] A 1623 report echoed the same problems, noting that the sea had caused a third of the southern wall to collapse; the necessary repairs, including strengthening the walls, were projected at £560.[29][lower-alpha 1]

Four years later, amid fears of war with France and Spain, the castle's captain, Richard Chalcroft, reported that the fortification was in such a poor condition that "neither habitable or defensible against any assault, nor any way fit to command the roads".[30] An inspection team observed that it was straightforward to climb over the castle's ruined walls and rotten timbers, and that as a result its artillery had been dismounted and placed along the beach instead.[30] The castle was probably not repaired, however, until after 1638.[31]

Sandgate Castle was seized in 1642 by Parliamentary forces at the start of the first English Civil War between the supporters of King Charles I and Parliament, although its captain, Richard Hippesley, remained in post.[32] The war ended in 1646 but, after the few years of unsteady peace, the Second Civil War broke out in 1648. The Parliamentary navy was based in Kent, protected by the other Henrician castles of Walmer, Deal and Sandown, but by May a Royalist insurrection was under way across the county, and the fleet joined the rebellion.[33] Sandgate and its sister castles were occupied by the Royalists.[34] Parliament defeated the wider insurgency at the Battle of Maidstone at the start of June, however, and then sent a force under the command of Colonel Rich to deal with the Kentish castles.[35] Sandgate was still occupied by the Royalists that August, when Rich sent forces to prevent its garrison intervening to disrupt his assault on Deal and Sandown, but was recaptured soon after.[36]

During the interregnum, Hippesley initially continued as captain of Sandgate, until he was replaced in 1653, resulting in complaints from him that he had been unfairly treated and that he was owed money by Parliament.[37] During this period the garrison was increased to include a governor, two corporals, twenty soldiers and three gunners.[26] When Charles II was restored to the throne in 1660, Sandgate and the other Device Forts initially remained at the heart of the south coast defences, but by now their design was antiquated.[38] The garrison was cut back to its pre-war levels, and then reduced further in 1682 to only ten men.[25] Sandgate had fallen into a poor condition, and £200 was assigned in 1663 for the repair of the castle, to be met partially from the proceeds of lands around Sandgate confiscated from former supporters of Parliament.[39][lower-alpha 1]

19th century

Sandgate Castle was still in use during the Napoleonic Wars at the start of the 19th century, but was heavily rebuilt. Brigadier-General William Twiss surveyed the south coast in 1804, and proposed building a series of 58 new defensive towers along it, as part of which he proposed converted Sandgate into a "secure sea battery".[40] After some opposition, and many delays within the War Office, the work on the castle finally began in 1805.[41]

The project lowered the height of the castle considerably, destroying much of the fortification in the process.[22] The upper storeys of the keep, the towers, the covered passageways and the gatehouse were all demolished, along with some of the buildings in the inner ward.[42] The resulting rubble was used to backfill the outer ward, raising its height and effectively turning the inner ward into a dry moat.[42] The inner curtain wall was reduced to one storey in height, and the outer curtain wall was refaced.[43] An esplanade and wall-walk were built around the remaining outer walls, which supported at least eight gun emplacements.[44]

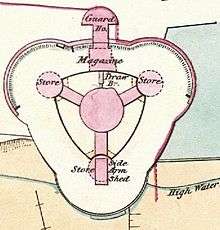

The circular keep was turned into a Martello tower, a type of Napoleonic artillery fortification.[22] It was now only two storeys tall, although remaining original interior walls and doorways largely survived untouched.[45] It was accessed on the first floor via an unusual sliding drawbridge, which was supported on rails and could retract into the floor, and the different storeys were linked by a spiral staircase.[46] The ground floor of the keep included a brick-built magazine, and the roof, supported by a central pillar running up through the building, held a single, large gun emplacement.[47]

The north-east and north-west towers, now only one-storey tall, were covered with turf, turning the rear of the outer ward into a flat, grassed esplanade.[48] The southern tower was reduced in height to two storeys, but remained in use as a gun platform.[49] The covered corridors between the keep and the towers were now one-storey high as well, linking to the buried towers in the north-east and north-west bastions.[50] The upper storeys of the gatehouse were rebuilt, although the ground floor remained in its 16th-century condition.[51]

The modified castle was completed by 1808, and held eight 24-pounder (11 kg) guns along the outer wall, a gun on the roof of the southern bastion, and another on top of the keep itself.[52] The new castle could hold a garrison of 40 men.[52]

In 1859, the castle was re-equipped with heavier artillery, a combination of 32-pounder (15 kg) and 68-pounder (31 kg) guns.[53] A new magazine was constructed, comprising a large, brick-built building divided into three rooms for storing gunpowder, specially designed to keep the powder dry.[54] The exterior gun emplacements were also redesigned, reusing the 1806 foundations; the two surviving emplacements, in the north-east and north-west bastions, date from 1859.[44]

Coastal erosion remained a problem. By the middle of the century, the tides had reached the southern edge of the castle, and an 1866 report stated that the walls had been undermined by the sea.[55] Despite protective piles being driven around the castle, it was badly affected by flooding in 1875 and 1878, creating serious fissures in the stonework.[56] The high costs of maintaining the property, combined with its dwindling utility, encouraged the government to sell the castle to the South Eastern Railway company in 1888, who intended to turn it into a railway station.[56] It was then sold to private owners and a small museum was created in the castle, which was sometimes opened to the public for an entry price of one penny.[57][lower-alpha 2]

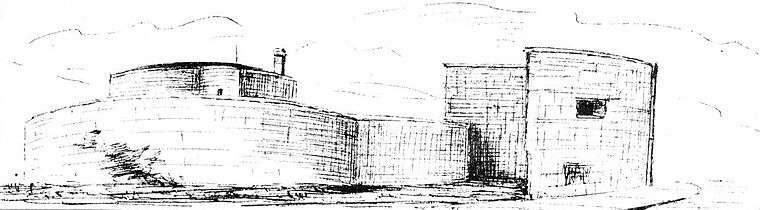

Sketches of Sandgate Castle in 1893 by E. Kennett, from the north-east...

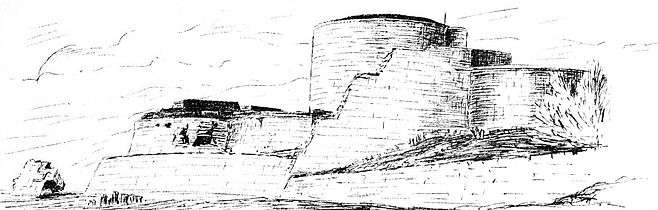

Sketches of Sandgate Castle in 1893 by E. Kennett, from the north-east... ...and the south-east

...and the south-east The main doorway into the gatehouse...

The main doorway into the gatehouse... ...and interior...

...and interior... and the keep.

and the keep.

20th–21st centuries

The receding coast line continued to threaten Sandgate Castle, and severe storms in 1927 and 1950 undermined large parts of the castle.[59] By the time that a new seawall was built in the early 1950s, the southern third of the castle had been entirely destroyed.[59]

In 1975, Peter and Barbara McGregor began to restore the ruins of the castle, with the support of the Department of the Environment, Kent County Council and the British Army.[60] As part of the project, archaeological investigations were carried out between 1975 and 1979 by Edward Harris.[60]

The part of the 1806 esplanade around the northeast bastion was excavated, revealing the lower 16th-century stonework of the tower and the east side of the 1859 magazine, and a retaining wall was built to support the newly exposed walls.[61] This created two levels in the outer bailey: a higher level on the western side, which still covered the northwest tower, and a lower one on the eastern.[61] The keep was turned into a private residence, with a new sun room built on top of the gun platform.[62]

In 2000, Lord Geoffrey Boot and his wife acquired the castle, which is now used by Boot's company, AMT South Eastern Ltd.[63]

The castle is protected under UK law as a grade I listed building.[64] The two 16th-century ledger books from the original construction, written by the project clerk Thomas Busshe, survive in the British Library.[65] They are 350 pages long, and form what the historian Peter Harrington has described as the "most complete building account of any Tudor fortification".[66]

See also

Notes

- Comparing early modern costs and prices with those of the modern period is challenging. £5,584 in 1540 could be equivalent to between £3.1 and £1,500 million in 2014, depending on the price comparison used. £260 in 1616 could equate to between £44,000 and £13.6 million; £560 in 123 to between £93,000 and £27.7 million; and £200 in 1663 to between £26,800 and £6 million. For comparison, the total royal expenditure on all the Device Forts across England between 1539 and 1547 came to £376,500, with St Mawes, for example, costing £5,018.[16]

- One penny in 1900 would be equivalent to £0.48 in 2014.[58]

References

- Thompson 1987, p. 111; Hale 1983, p. 63

- King 1991, pp. 176–177

- Morley 1976, p. 7

- Hale 1983, p. 63; Harrington 2007, p. 5

- Morley 1976, p. 7; Hale 1983, pp. 63–64

- Hale 1983, p. 66; Harrington 2007, p. 6

- Harrington 2007, p. 11; Walton 2010, p. 70

- Harris 1980, pp. 54–55; Rutton 1893, p. 229

- Walton 2010, p. 71; Harrington 2007, p. 18

- Saunders 1989, p. 46; Rutton 1893, p. 235

- Saunders 1989, p. 46

- Harris 1980, p. 81

- Rutton 1893, pp. 234–235; Harris 1980, p. 55

- Rutton 1893, pp. 235–237; Darvill & McWhirr 1984, p. 250

- Harrington 2007, p. 8

- Biddle et al. 2001, p. 12; Lawrence H. Officer; Samuel H. Williamson (2014), "Five Ways to Compute the Relative Value of a UK Pound Amount, 1270 to Present", MeasuringWorth, retrieved 29 May 2015

- "Sandgate Castle", Historic England, retrieved 26 November 2015; Harris 1980, p. 74

- "Sandgate Castle", Historic England, retrieved 26 November 2015

- Harris 1980, pp. 72–73; "Sandgate Castle", Historic England, retrieved 26 November 2015

- Harris 1980, p. 68

- Harris 1980, p. 54

- Harris 1980, pp. 81–82

- Harris 1980, p. 80; Rutton 1895, p. 244; Saunders 1989, p. 46

- Rutton 1895, pp. 244–246

- Rutton 1895, p. 248

- Rutton 1895, p. 247

- Harris 1980, p. 81; Rutton 1895, pp. 248–249

- Harris 1980, p. 81; Rutton 1895, p. 249

- Rutton 1895, p. 249

- Rutton 1895, pp. 249–250

- Rutton 1895, p. 250

- Rutton 1895, pp. 250–251

- Harrington 2007, p. 50; Kennedy 1962, pp. 248-–252

- Rutton 1895, p. 250; Kennedy 1962, pp. 251–252

- Ashton 1994, p. 440; Harrington 2007, p. 51

- Harrington 2007, p. 51; Ashton 1994, p. 442; Elvin 1894, pp. 110–111; Rutton 1895, p. 250

- Rutton 1895, p. 251

- Rutton 1895, p. 248; Tomlinson 1973, p. 6

- Rutton 1895, p. 251; Tomlinson 1973, p. 6

- Harris 1980, p. 81; Sutcliffe 1973, p. 55

- Harris 1980, p. 81; Sutcliffe 1973, p. 58

- Harris 1980, pp. 72, 81

- Harris 1980, pp. 65, 68

- Harris 1980, p. 66

- Harris 1980, pp. 73, 77

- Harris 1980, p. 77

- Harris 1980, pp. 73, 77, 81–82

- Harris 1980, p. 56

- Harris 1980, pp. 84–85

- Harris 1980, p. 73

- Harris 1980, pp. 54, 60, 6

- Harris 1980, p. 82

- Harris 1980, pp. 82, 86

- Harris 1980, pp. 70–72

- Tapete et al. 2013, p. 456; Rutton 1893, p. 253; Harris 1980, p. 54

- Rutton 1893, p. 253; Harris 1980, p. 54

- Harris 1980, p. 54; Harper 1914, pp. 316-217

- Lawrence H. Officer; Samuel H. Williamson (2014), "Five Ways to Compute the Relative Value of a UK Pound Amount, 1270 to Present", MeasuringWorth, retrieved 29 May 2015

- Tapete et al. 2013, p. 456; Harris 1980, p. 54

- Harris 1980, pp. 53, 86

- Harris 1980, pp. 53, 56, 86

- Clements 2011, p. 55

- "Burglar Fails to Break into Geoffrey Boot's Sandgate Castle Home", Dover Express, archived from the original on 19 November 2015, retrieved 19 November 2015; "Colourful Past of new MKH Baron Boot", Chad, archived from the original on 19 November 2015, retrieved 19 November 2015

- English Heritage, "Sandgate Castle, Sandgate", British Listed Buildings, retrieved 19 November 2015

- Rutton 1893, p. 228

- Harrington 2007, p. 18; Rutton 1893, p. 228

Bibliography

- Ashton, Robert (1994). Counter-revolution: The Second Civil War and Its Origins, 1646–8. Avon, UK: The Bath Press. ISBN 9780300061147.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Biddle, Martin; Hiller, Jonathon; Scott, Ian; Streeten, Anthony (2001). Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation. Oxford, UK: Oxbow Books. ISBN 0904220230.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Clements, Bill (2011). Martello Towers Worldwide. Barnsley, UK: Sword and Pen. ISBN 9781848845350.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Darvill, Tim; McWhirr, Alan (1984). "Brick and Tile Production in Roman Britain: Models of Economic Organisation". World Archaeology. 15 (3): 239–261. doi:10.1080/00438243.1984.9979904.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Elvin, Charles R. S. (1894). The History of Walmer and Walmer Castle. Canterbury, UK: Cross and Jackman. OCLC 23374336.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Harper, Charles G. (1914). The Kentish Coast. London, UK: Chapman and Hall. OCLC 1319228.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Harrington, Peter (2007). The Castles of Henry VIII. Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 9781472803801.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hale, John R. (1983). Renaissance War Studies. London, UK: Hambledon Press. ISBN 0907628176.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Harris, Edward C. (1980). "Archaeological Investigations at Sandgate Castle, Kent, 1976-9". Post-Medieval Archaeology. 14: 53–88. doi:10.1179/pma.1980.003.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kennedy, D. E. (1962). "The English Naval Revolt of 1648". The English Historical Review. 77 (303): 247–256. doi:10.1093/ehr/lxxvii.ccciii.247.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- King, D. J. Cathcart (1991). The Castle in England and Wales: An Interpretative History. London, UK: Routledge Press. ISBN 9780415003506.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Morley, B. M. (1976). Henry VIII and the Development of Coastal Defence. London, UK: Her Majesty's Stationery Office. ISBN 0116707771.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rutton, W. L. (1893). "Sandgate Castle, AD 1539–40". Archaeologia Cantiana. 20: 228–257.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rutton, W. L. (1895). "Sandgate Castle". Archaeologia Cantiana. 21: 244–259.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Saunders, Andrew (1989). Fortress Britain: Artillery Fortifications in the British Isles and Ireland. Liphook, UK: Beaufort. ISBN 1855120003.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sutcliffe, Sheila (1973). Martello Towers. Rutherford, US: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 9780838613139.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tapete, Deodato; Bromhead, Edward; Ibsen, Maia; Casagli, Nicola (2013). "Coastal Erosion and Landsliding Impact on Historic Sites in SE Britain". In Margottini, Claudio; Canuti, Paolo; Sassa, Kyoji (eds.). Landslide Science and Practice: Volume 6, Risk Assessment, Management and Migitation edited by Claudio Margottini, Paolo Canuti, Kyoji Sassa. Heidelberg, Germany: Springer. pp. 451–458. ISBN 9783642313196.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Thompson, M. W. (1987). The Decline of the Castle. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 1854226088.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tomlinson, Howard (1973). "The Ordnance Office and the King's Forts, 1660–1714". Architectural History. 1: 5–25.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Walton, Steven A. (2010). "State Building Through Building for the State: Foreign and Domestic Expertise in Tudor Fortification". Osiris. 25 (1): 66–84. doi:10.1086/657263.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sandgate Castle. |