Hull Castle

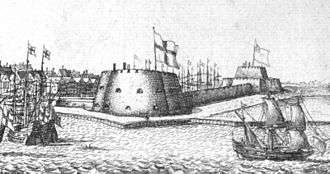

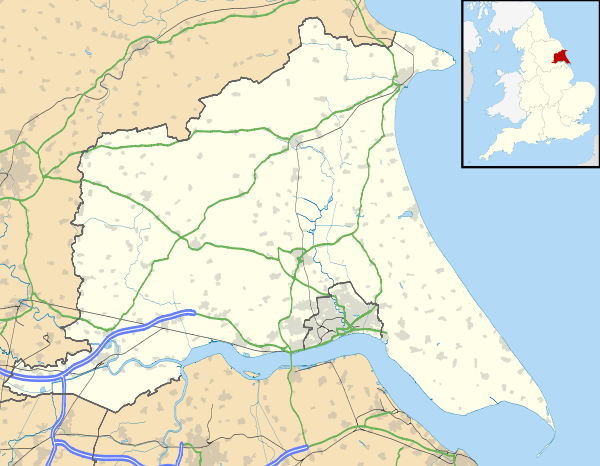

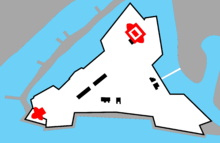

Hull Castle was an artillery fort in Kingston upon Hull in England. Together with two supporting blockhouses, it defended the eastern side of the River Hull, and was constructed by King Henry VIII to protect against attack from France as part of his Device programme in 1542. The castle had two large, curved bastions and a rectangular keep at its centre; the blockhouses to the north and south had three curved bastions supporting guns, and a curtain wall and moat linked the blockhouses and castle. The construction project used material from recently dissolved monasteries, and cost £21,056.[lower-alpha 1] The town took over responsibility for these defences in 1553, leading to a long running dispute with the Crown as to whether the civic authorities were fulfilling their responsibilities to maintain them.

| Hull Castle | |

|---|---|

South Blockhouse (centre) and Hull Castle (right) viewed from the sea, Wenceslas Hollar, mid-17th century | |

Hull Castle | |

| Coordinates | 53.74339°N 0.326679°W |

| Type | Device Fort |

| Site information | |

| Condition | Only foundations remain |

| Site history | |

| Materials | Brick and stone |

| Demolished | 1801, 1864 |

| Events | English Civil War |

During the 16th and 17th centuries, the defences were used to imprison Catholic recusants, who were often held in harsh conditions. The castle and blockhouses saw service during the sieges of the English Civil War in the 1640s, and remained in used during the interregnum. After the restoration of Charles II, the buildings were neglected until the King redeveloped the eastern defences of Hull in 1681, creating a larger fortification called the Citadel. The castle and the South Blockhouse formed part of the new design, although the North Blockhouse was allowed to fall into ruins and finally demolished in 1801. The former buildings remained in use, with various modifications, until the Citadel was demolished in 1864 to allow the construction of new docks. The foundations survived and have been the subject of archaeological investigations.

History

16th century

Background

Hull Castle was built as a consequence of international tensions between England, France and the Holy Roman Empire in the final years of the reign of King Henry VIII. Traditionally the Crown had left coastal defences to local lords and communities, only taking a modest role in building and maintaining fortifications, and while France and the Empire remained in conflict, maritime raids were common but an actual invasion of England seemed unlikely.[1] Modest defences based around simple blockhouses and towers existed in the south-west and along the Sussex coast, with a few more impressive works in the north of England, but in general the fortifications were limited in scale.[2]

In 1533, Henry broke with Pope Paul III over the annulment of his long-standing marriage to Catherine of Aragon.[3] Catherine was the aunt of Charles V, the Holy Roman Emperor, who took the annulment as a personal insult.[4] This resulted in France and the Empire declaring an alliance against Henry in 1538, and the Pope encouraging the two countries to attack England.[5] An invasion of England appeared certain.[6] In response, Henry issued an order, called a "device", in 1539, giving instructions for the "defence of the realm in time of invasion" and the construction of forts along the English coastline.[7] The immediate threat passed, but resurfaced in 1544, with France threatening an invasion across the English Channel, backed by her allies in Scotland.[8] Henry therefore issued another device to further improve the country's defences.[9]

Construction

Hull Castle was constructed to defend the east side of the town of Kingston upon Hull against a possible French attack; it was also intended to ensure the loyalty of the population, who had taken part in a revolt against the King in 1536.[10] Henry had visited Hull in late 1541 and had observed that, although the town had strong walls to the north and west, it lacked adequate defences in the event of an attack from the east, while the harbour was only protected by a "little round brick tower".[11] Henry issued orders for the existing town defences to be repaired and renovated but, before the work could commence, he changed his mind and issued fresh instructions in early 1542.[12] John Rogers, a military engineer previously stationed in Guînes, was brought back to England to construct a major system of defences on the east bank of the River Humber, comprising a central castle linked to two large blockhouses.[11]

The design of the new defences was probably carried out by Rogers and resembled his earlier work near Calais, although the King probably also made some decisions on the project personally.[13] Sir Richard Long and Michael Stanhope were instructed to oversee the construction of the defences, with Thomas Aldred acting as the project's paymaster and William Reynolds in the role of master mason.[14] Initial estimates suggested that 530 workers would be needed, including masons, carpenters and plumbers, but more may have been required in practice.[14] Some of the building materials were taken from monastic institutions, which had recently dissolved by Henry; stone and lead was taken from the nearby Meaux Abbey, further stone from the friaries in Hull and probably also from St Mary's Church in Hull, which had recently collapsed.[15] At least some of the bricks needed were made in a series of ten kilns beside the site itself.[16] The land needed for the buildings had been seized during the dissolution of the monasteries.[17] By December 1543, £21,056 had been spent on the project.[16][lower-alpha 1]

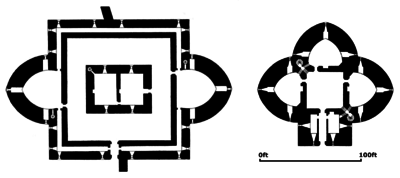

The castle was rectangular, with brick and stone foundations and a brick superstructure.[19] It had two large, curved bastions containing chambers on the west and east ends, and a three-storey rectangular keep in the middle, 66 by 50 feet (20 by 15 m) across, set within an inner courtyard.[20] The outer wall was 19 feet (5.8 m) thick and contained a gallery and ports for hand-guns, and supported two tiers of artillery.[21] A moat ran around the outside of the castle.[17] The two-storey tall blockhouses were also built from brick and stone, and each had a square central tower and entrance at the rear, and three curved bastions to the front and sides.[20] Their walls were 16 feet (4.9 m) thick, sloped so as to deflect incoming fire, and supported two tiers of guns; the interiors were partitioned, to reduce the risk of explosions damaging the entire fortification.[22] The use of bastions adopted some features from the Italian-style of defences then popular on the continent, but their design was imperfect and failed to provide flanking cover or interlink with the neighbouring defences.[23] A crenellated curtain wall, approximately 900 metres (3,000 ft) long and 12 feet (3.7 m) high, linked the blockhouses and castle, with a wet moat on the eastward side.[24]

Operation

After the construction, Sir Richard Long and Michael Stanhope were placed in command of the castle and blockhouses; the initial garrison may have been substantial, costing around £1,000 a year, but this was mostly demobilised at the end of 1542.[26] Nonetheless, the castle and blockhouses still proved expensive to maintain.[27] As a result, in 1553, an agreement was reached with the corporation of Hull, under which the town would take over responsibility for their maintenance, in exchange for an annual grant of £50 from various local manors.[28][lower-alpha 1] The town provided a bond of £2,000 as a commitment that it would keep its commitments.[29] The mayor of Hull also took over the role of the Governor of Hull, with "keepers" were appointed by the town to run each of the buildings; the pasture land behind the fortifications was rented out to bring in income.[30]

Arguments soon broke out between the Crown and the corporation over the deal.[31] The Crown argued that the corporation was not adequately maintaining the castle and blockhouses.[32] The Earl of Sussex complained in 1569 that they were in need of repair, and a 1576 survey stated that their gun platforms were in poor condition and that the ditches had become clogged with earth, while coastal erosion had undermined the South Blockhouse.[33] Queen Elizabeth I provided 300 trees to help the repair work and a new jetty was built to protect the southern end of the defences from the sea.[34] The Crown gave 60 trees to the town to help with further repairs in 1581.[31] Fears of a Spanish invasion resulted in fresh repairs being carried out, and the threat of the Armada in 1588 resulted in proposals to build additional earthworks around the blockhouses, but nothing appear to have actually been carried out.[35] The dispute over maintenance between the Crown and the town finally came to court in 1588; the corporation argued that green timber had been used in the original construction work and claimed that they had spent £2,893 between 1552 and 1587 on the defences: the Crown's case failed.[31]

A new bridge, North Bridge, was built over the River Hull in the 1540s, protected by artillery in the North Blockhouse.[17] From 1577 onwards, the castle and blockhouses began to be used to contain Catholic recusants, with as many as 16 prisoners being known to have been detained at any one time.[36] The ground-floor of the South Blockhouse was often used for this purpose; the conditions were particularly poor, with contemporary accounts noting that the quarters "have been overflowed with water at high tide, so that they walked, the earth was so raw and moist that their shoes would cleave to the ground".[36] Another Spanish invasion scare in 1597 led to the castle and blockhouses being put on alert, and the recusants were temporarily removed for security reasons.[37]

17th century

The arguments over the maintenance of the castle and blockhouses continued in early 1600s. The town of Hull argued that since the revenues of £50 granted in 1553 were insufficient to maintain these defences, they should be allowed to use royal customs duties to assist in the work, particularly in protecting the east bank of the river from erosion.[38] As a result, another court case was brought by the Crown in 1601.[31] A commission was established to examine the defences and concluded that the position of the castle meant that it was militarily useless, and as a consequence it had not been garrisoned or maintained for many years, resulting in it falling into total disrepair.[39] The commission's report led to the town carrying repairs to the earthwork defences over the coming year.[40] The Crown dropped its law case, but a third case was brought in 1634, only to see the Crown pull out of the proceedings once again.[41] By now, the corporation argued it had spent £11,367 on the defences.[31]

Around 1627, Robert Morton, the mayor of Hull, had an additional rectangular earthwork battery of four guns constructed around the south blockhouse to defend the estuary against a potential Spanish and French invasion threat.[42] The South End Fort was built on the other side of the river from the South Blockhouse at the same time, provided supporting crossfire.[40] In 1634, a survey showed the North Blockhouse to be mounting 24 pieces of artillery, the castle 29, and the South Blockhouse 24 guns.[40] Catholic recusants continued to be detained in the castle and blockhouses, where they were ill-treated by the keepers, typically men with strong Puritan sympathies.[43]

At the outbreak of the English Civil War in 1642, Hull sided with Parliament against King Charles I.[44] Hull was besieged by the Royalists in July 1642, and the South Blockhouse may have been used to drive off a Royalist naval vessel approaching the estuary.[45] In 1643, the mayor, Thomas Raikes, and the Parliamentarians in Hull concluded that the governor, Sir John Hotham, was planning to seize the castle and the wider town for the King.[46] In a pre-emptive strike in June, Captain Moyer landed 100 troops from the Parliamentary warship the Hercules and took the castle and blockhouses, while Raikes seized the town itself.[46] Hotham was later executed.[46] A further siege followed in 1643, during which the area to the east of the castle and blockhouses was deliberately flooded by the defenders to provide additional protection.[47] In September, the south bastion of the North Blockhouse was accidentally blown up by one of the defenders, killing five men.[47]

The artillery exchanges during the sieges and the activities of the garrisons had caused considerable damage, and at the end of the conflict the military Governor of Hull ordered repairs.[48] The North Blockhouse needed work costing £1,500, Hull Castle, £300, and the South Blockhouse, £220.[48][lower-alpha 1] During the interregnum, the fortifications were maintained, despite complaints from the town at the costs, and were used to hold both prisoners of war and political prisoners.[49] Henry Slingsby, for example, was held at the castle before his trial in London.[50]

When Charles II was restored to the throne in 1660, the interregnum army was demobilised; a guard-force remained in Hull to protect the arsenal there, being officially referred to as the "Hull Blockhouse" garrison.[51] All three sites were garrisoned: surveys reported that the South Blockhouse was in a good condition and held 21 guns, the castle was in a poor condition and held only 8 light guns, and the North Blockhouse was in a "ruinous" condition and held 10 guns.[52] An order was taken to strip the most ruined parts of the North Blockhouse of its timber, bricks and lead to help improve the remainder, supplemented by additional supplies of timber and bricks donated by the Crown, but the material was misappropriated and used, in part, for construction work on the houses of the Governor and his deputy.[53]

The defences were neglected for several decades, despite calls for improvements and when the military engineer Sir Martin Beckman visited the sites in 1681, he concluded that they were "very much out of repair": the North Blockhouse was "altogether dismantled", the South Blockhouse needed extensive repairs and the moat had been left to entirely silt up.[54] Recusants continued to be detained in the castle, which was regarded by the national authorities as a particularly suitable prison for this class of prisoner.[55]

The Crown decided to construct a new, triangular fortification called the Hull Citadel on the eastern side of the river, incorporating the castle and the South Blockhouse.[16] Beckman was responsible for the design and the work took place between 1681 and 1690 at a cost of over £100,000.[56][lower-alpha 1] The South Blockhouse was repaired and strengthened with a water bastion, and formed the south-west corner of the Citadel; the castle was integrated into the north corner and protected by a new bastion.[57] The intervening curtain wall was partially demolished to make way for the new works, while the last remains of the moat were filled in with clay.[58] By 1699, the castle itself no longer held any guns, although the South Bastion was equipped with three demi-culverins and four sakers, all which were inoperable due to poor maintenance and the effect of the sea.[59] The new fortifications were protected by a combination of soldiers from the regular Army, from Independent Companies under the control of the governor, and the "Castle Guard" of local soldiers.[60]

18th–21st centuries

The castle and the South Blockhouse continued in use within the Citadel during the 18th and early 19th centuries.[61] In 1746, the South Blockhouse was redesigned with new embrasures, but the fortifications were largely neglected.[62] During the Napoleonic Wars, the Citadel was extensively repaired; the South Blockhouse was extensively altered to allow it to hold naval ordnance stores and the castle became an armoury, each wing able to hold 20,000 stands of infantry weapons and 3,000 cavalry arms.[63] The North Blockhouse and the remnants of the curtain wall beyond the Citadel were in ruins by 1766; the blockhouse was let to private contractors, and then demolished altogether between 1801 and 1802.[64]

By the 19th century, extensive docks had grown up around the Citadel and in 1802 the surrounding land was granted to the Hull Dock Company.[65] The Citadel remained in military use until 1848, by when developments in military technology had made the fortification obsolete.[66] In 1858 there were proposals to turn the site into a public park, but instead the Citadel, including Hull Castle and the South Blockhouse, was demolished in 1864 to make way for an expansion of the docks.[16]

From 1969 onwards there have been a range of archaeological investigations around the area.[67] The foundations of the Citadel, which had been too substantial to dismantle in the 19th century, were uncovered during urban regeneration works in 1987, and archaeological digs have occurred on both the castle and the South Blockhouse sites.[68] The foundations of these two buildings, along with the southern end of the Citadel remains, are protected under UK law as an Ancient Monument.[69] During excavations in 1997, an iron portpiece was discovered on the site of the South Blockhouse.[70] The weapon, now known as "Henry's Gun", is one of only four such guns in the world to have survived from the period and is displayed at the Hull Museums.[70] It was either made by Henry VIII's gun-maker or acquired from the Low Countries.[70] By 1681 it would have been obsolete and was disposed of in 1681 during the construction of the Citadel.[70]

Notes

- Comparing early modern costs and prices with those of the modern period is challenging. £21,056 in 1543 could be equivalent to between £120 million and £4,800 million in 2015 terms, depending on the price comparison used. For comparison, the total royal expenditure on all the Device Forts across England between 1539–47 came to £376,500, with Sandgate Castle, for example, costing £5,584. £1,000 in 1543 could be equivalent to between £5.5 and £230 million, and £50 in 1553 to between £276,000 and £11 million. The total cost of the 1645 repair works was £2,020, worth between £4.7 million and £91 million in 2015 terms. £100,000 in 1690 could equate to between £201 million and £2,900 million.[18]

References

- Thompson 1987, p. 111; Hale 1983, p. 63

- King 1991, pp. 176–177

- Morley 1976, p. 7

- Hale 1983, p. 63; Harrington 2007, p. 5

- Morley 1976, p. 7; Hale 1983, pp. 63–64

- Hale 1983, p. 66; Harrington 2007, p. 6

- Harrington 2007, p. 11; Walton 2010, p. 70

- Hale 1983, p. 80

- Harrington 2007, pp. 29–30

- Colvin, Ransome & Summerson 1982, pp. 472, 474; Howes & Foreman 1999, p. 6

- Colvin, Ransome & Summerson 1982, p. 472

- Colvin, Ransome & Summerson 1982, pp. 473–474

- Colvin, Ransome & Summerson 1982, p. 474; Howes & Foreman 1999, p. 12

- Colvin, Ransome & Summerson 1982, p. 474

- Colvin, Ransome & Summerson 1982, p. 475; Howes & Foreman 1999, p. 13

- Colvin, Ransome & Summerson 1982, p. 475

- Howes & Foreman 1999, p. 13

- Biddle et al. 2001, p. 12; Lawrence H. Officer; Samuel H. Williamson (2014), "Five Ways to Compute the Relative Value of a UK Pound Amount, 1270 to Present", MeasuringWorth, retrieved 29 May 2015

- Colvin, Ransome & Summerson 1982, p. 475; Howes & Foreman 1999, p. 12

- Colvin, Ransome & Summerson 1982, p. 475; Howes & Foreman 1999, p. 12; K. J. Alison (1969), "Fortifications", British History Online, retrieved 12 June 2016

- Colvin, Ransome & Summerson 1982, pp. 475–476

- Colvin, Ransome & Summerson 1982, pp. 475–476; Howes & Foreman 1999, p. 12

- Colvin, Ransome & Summerson 1982, p. 476; Saunders 1989, pp. 49–50

- Howes & Foreman 1999, pp. 12–13, 24; K. J. Alison (1969), "Fortifications", British History Online, retrieved 12 June 2016

- Hirst 1913, pp. 123–126

- Howes & Foreman 1999, p. 14

- Colvin, Ransome & Summerson 1982, p. 475; Howes & Foreman 1999, p. 16; Hirst 1895, p. 30

- Colvin, Ransome & Summerson 1982, p. 475; K. J. Alison (1969), "Fortifications", British History Online, retrieved 12 June 2016

- Howes & Foreman 1999, p. 16

- Howes & Foreman 1999, p. 16; K. J. Alison (1969), "Fortifications", British History Online, retrieved 12 June 2016

- K. J. Alison (1969), "Fortifications", British History Online, retrieved 12 June 2016

- K. J. Alison (1969), "Fortifications", British History Online, retrieved 12 June 2016; Hirst 1895, p. 30

- K. J. Alison (1969), "Fortifications", British History Online, retrieved 12 June 2016; Hirst 1895, p. 30; Howes & Foreman 1999, p. 17

- Howes & Foreman 1999, p. 17

- Howes & Foreman 1999, p. 18

- Howes & Foreman 1999, p. 19

- Howes & Foreman 1999, pp. 18–19

- K. J. Alison (1969), "Fortifications", British History Online, retrieved 12 June 2016; Howes & Foreman 1999, p. 21

- Hirst 1895, p. 31

- Howes & Foreman 1999, p. 23

- K. J. Alison (1969), "Fortifications", British History Online, retrieved 12 June 2016; Hirst 1895, p. 31

- K. J. Alison (1969), "Fortifications", British History Online, retrieved 12 June 2016; Hirst 1895, p. 31; Howes & Foreman 1999, pp. 21, 23

- Howes & Foreman 1999, p. 21

- Howes & Foreman 1999, p. 27

- Howes & Foreman 1999, pp. 27–28

- Hirst 1895, p. 32

- Howes & Foreman 1999, p. 34

- Howes & Foreman 1999, p. 41

- Howes & Foreman 1999, pp. 42, 44

- Howes & Foreman 1999, p. 44

- Howes & Foreman 1999, pp. 49, 51

- Howes & Foreman 1999, p. 54; Hirst 1895, p. 34

- Howes & Foreman 1999, p. 53; Hirst 1895, pp. 34–35

- Howes & Foreman 1999, p. 58

- Hirst 1895, p. 36

- Howes & Foreman 1999, pp. 56, 59

- Howes & Foreman 1999, pp. 59, 61, 72–73

- Howes & Foreman 1999, pp. 74, 76

- Howes & Foreman 1999, pp. 142–143

- Howes & Foreman 1999, pp. 119–120

- Howes & Foreman 1999, p. 149; K. J. Alison (1969), "Fortifications", British History Online, retrieved 12 June 2016

- Howes & Foreman 1999, pp. 149–152

- Howes & Foreman 1999, pp. 166, 169; "Hull Castle, South Blockhouse and part of late 17th century Hull Citadel Fort at Garrison Side", Historic England, retrieved 12 June 2016

- Colvin, Ransome & Summerson 1982, p. 475; Hirst 1895, p. 38; Howes & Foreman 1999, p. 155

- Hirst 1895, p. 38

- Hirst 1895, p. 38; "Hull Castle, South Blockhouse and part of late 17th century Hull Citadel Fort at Garrison Side", Historic England, retrieved 12 June 2016

- "Hull Castle, South Blockhouse and part of late 17th century Hull Citadel Fort at Garrison Side", Historic England, retrieved 12 June 2016; Colvin, Ransome & Summerson 1982, p. 475

- Howes & Foreman 1999, p. 174; "Hull Castle, South Blockhouse and part of late 17th century Hull Citadel Fort at Garrison Side", Historic England, retrieved 12 June 2016

- "Hull Castle, South Blockhouse and part of late 17th century Hull Citadel Fort at Garrison Side", Historic England, retrieved 12 June 2016

- "Henry's Gun", Hull City Council, retrieved 4 June 2016

Bibliography

- Biddle, Martin; Hiller, Jonathon; Scott, Ian; Streeten, Anthony (2001). Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation. Oxford, UK: Oxbow Books. ISBN 0904220230.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Colvin, H. M.; Ransome, D. R.; Summerson (1982). The History of the King's Works, Volume 4: 1485–1660, Part 2. London, UK: HMSO. ISBN 0116708328.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hale, J. R. (1983). Renaissance War Studies. London, UK: Hambledon Press. ISBN 0907628176.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Harrington, Peter (2007). The Castles of Henry VIII. Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 9781472803801.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hirst, Joseph H. (1895). "Castle of Kingston-upon-Hull". East Riding Antiquarian Society. 3: 24–39.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hirst, Joseph H. (1913). The Block houses of Kingston-upon-Hull and Who Went There (2nd ed.). London, UK: A. Brown. OCLC 9926474.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Howes, Audrey; Foreman, Martin (1999). Town and Gun: The 17th-Century Defences of Hull. Kingston upon Hull, UK: Kingston Press. ISBN 1902039025.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- King, D. J. Cathcart (1991). The Castle in England and Wales: An Interpretative History. London, UK: Routledge Press. ISBN 9780415003506.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Morley, B. M. (1976). Henry VIII and the Development of Coastal Defence. London, UK: Her Majesty's Stationery Office. ISBN 0116707771.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Saunders, Andrew (1989). Fortress Britain: Artillery Fortifications in the British Isles and Ireland. Liphook, UK: Beaufort. ISBN 1855120003.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Thompson, M. W. (1987). The Decline of the Castle. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 1854226088.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Walton, Steven A. (2010). "State Building Through Building for the State: Foreign and Domestic Expertise in Tudor Fortification". Osiris. 25 (1): 66–84. doi:10.1086/657263.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)