Saint Menas

Saint Menas (also Mina, Minas, Mena; Coptic: Ⲁⲃⲃⲁ Ⲙⲏⲛⲁ; 285 – c. 309), a martyr and wonder-worker, is one of the most well-known Coptic Saints in the East and the West, due to the many miracles that are attributed to his intercession and prayers. Minas was a Coptic soldier in the Roman army martyred because he refused to recant his Christian faith. The common date of his commemoration is November 11, which occurs 13 days later (November 24) on the Julian calendar.

Saint Mina | |

|---|---|

Jesus and Minas, 6th-century icon from Bawit in Middle Egypt, currently at Louvre; One of the oldest known icons in existence | |

| Martyr and wonder-worker | |

| Born | 285 Nikiou, Egypt, Roman Empire |

| Died | c. 309 Phrygia, Anatolia, Roman Empire (modern-day Turkey) |

| Venerated in | Oriental Orthodoxy Eastern Orthodox Church Roman Catholic Church |

| Canonized | Pre-Congregation |

| Major shrine | Monastery of Saint Mina Church of Saint Menas (Cairo) |

| Feast | |

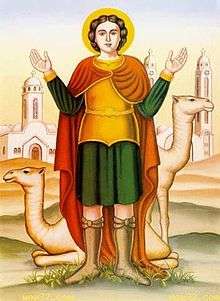

| Attributes | Christian Martyrdom, man with his hands cut off and his eyes torn out; man with two camels; young knight with a halberd, an anachronistic depiction of his time in the Roman army |

| Patronage | falsely accused people; peddlers; traveling merchants; Heraklion |

His feast day is celebrated every year on 15 Hathor in the Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria, which corresponds to November 24 on the Gregorian Calendar. In Eastern Orthodox Churches that follow the old style or Julian calendar, it is likewise celebrated on November 24. In the Eastern Orthodox Churches that follow the new style or Revised Julian calendar, as well as in the Catholic Church, it is celebrated on November 11.

Although Minas is recognized as a minor saint in Western churches, it is considered likely by many historians that he is celebrated in these churches under the name of Saint Christopher (i.e. the "Christ-bearer"), as one of the legends associated with Mina has him, like Christopher, carrying the Christ Child.

Origin of his name

Mina was his original name, according to the story his mother called him "Mēna" because she heard a voice saying amēn. Minas (Μηνᾶς) is how he is known in Greek, while in Armenian and Arabic he is known as "Mīna" (مينا).

Life and martyrdom

There are many sources written in different languages (Koine Greek, Coptic, Old Nubian, Ge'ez, Latin, Syriac, Armenian) relating to Menas.[3]

Menas was born in Egypt in 285 in the city of Nikiou,[4] which lay in the vicinity of Memphis. His parents were ascetic Christians but did not have any children for a long time. His father's name was Eudoxios and his mother's name was Euphemia. On the feast of Mary, mother of Jesus, Euphemia was praying in front of an icon of Mary with tears that God may give her a blessed son. A sound came from the icon saying "Amen". A few months later, Euphemia gave birth to a boy and named him Menas.[5]

Eudoxios, a ruler of one of the administrative divisions of Egypt, died when Menas was fourteen years old. At the age of fifteen Menas joined the Roman army and was given a high rank due to his father's reputation. Most sources state that he served in Cotyaeus in Phrygia,[6] although some say his appointment was in Algeria.[5] Three years later he left the army, longing to devote his whole life to Christ, and headed towards the desert to live a different kind of life.

After spending five years as a hermit, Menas saw in a revelation the angels crowning the martyrs with glorious crowns, and longed to join those martyrs. While he was thinking about it, he heard a voice saying: "Blessed are you Menas because you have been called to the pious life from your childhood. You shall be granted three immortal crowns: one for your celibacy, another for your asceticism, and a third for your martyrdom." Menas subsequently hurried to the ruler, declaring his Christian faith.[7]

Relics

The soldiers who executed Menas set his body on fire for three days but the body remained unharmed. Menas' sister then bribed the soldiers and managed to carry the body away. She embarked on a ship heading to Alexandria, where she placed the saint's body in a church.

When the time of persecution ended, during the papacy of Athanasius of Alexandria the Pope had a vision of an angel appearing to him and ordering him to load Menas' body on a camel and head towards the Libyan Desert. At a certain spot near a water well at the end of Lake Mariout, not far from Alexandria, the camel stopped and wouldn't move. The Christians took this a sign from God and buried Menas' body there.

The Berbers of Pentapolis rose against the cities around Alexandria. As the people were getting ready to face them, the Roman governor decided to secretly take the body of Menas with him to be his deliverer and his strong protector. Through the saint's blessings, the governor overcame the Berbers and returned victorious. However, he decided not to return the body to its original place and wanted to take it to Alexandria. On the way back, as they passed by Lake Mariout at the same spot where the body was originally buried, the camel carrying the body knelt down and would not move. People moved the body to another camel, but the second camel would not move either.[8] The governor finally realized that this was God's command. He made a coffin from decay-resistant wood and placed the silver coffin in it.

Veneration

Most versions of the story state that the location of the tomb was then forgotten until its miraculous rediscovery by a local shepherd. A shepherd was feeding his sheep in that location, and a sick lamb fell on the ground. As it struggled to get on its feet again, its scab was cured. The story spread quickly and the sick who came to this spot recovered from whatever illnesses they had just by lying on the ground. The Ethiopian Synaxarium describes Constantine I sending his sick daughter to the shepherd to be cured, and credits her with finding Mina's body, after which Constantine ordered the construction of a church at the site. Some versions of the story replace Constantine with the late-5th century emperor Zeno, but archaeologists have dated the original foundation to the late 4th century.[9] According to the Zeno version, his daughter was leprous and his advisors suggested that she should try that place, and she did. At night Saint Mina appeared to the girl and informed her that his body was buried in that place. The following morning, Zeno's daughter was cured and she related her vision about the saint to her servants. Zeno immediately ordered Mina's body to be dug out and a cathedral to be built there.

After his martyrdom in the early fourth century, Mina acquired a reputation for miraculous healing powers. The cult of St Mina was centered on Abu Mena near Alexandria.[10] Sick people from all over the Christian world used to visit that city and were healed through the intercessions of Saint Mina, who became known as the Wonders' Maker. Today, numerous little clay Menas flasks, or bottles for holy water or oil on which the saint's name and picture are stamped, are found by archeologists in diverse countries around the Mediterranean world, such as Heidelberg in Germany, Milan in Italy, Dalmatia in Croatia, Marseille in France, Dongola in Sudan, Meols (Cheshire) in England, and the holy city of Jerusalem, as well as modern Turkey and Eritrea. Pilgrims would buy these bottles and take them back to their relatives.[5]

Patronage

Mina is the patron saint of many German and Swiss towns. He was venerated as the protector of pilgrims and merchants.[11] St. Menas is also noted for healing various illnesses.[2]

Iconography

Mina is generally shown between two camels, the animals that, according to the legend, returned his body to Egypt for burial.[3]

Military saint

Most likely Mina of Mareotis, Mina of Cotyaes, and Mina of Constantinople, are all the same person honored in different places.[6] Mina is sometimes called Mina the Soldier also called the "Wonder worker" in the West, where he is venerated as a military saint.

New Monastery and Cathedral of Saint Mina

As soon as Pope Cyril VI of Alexandria became Pope and Patriarch on Saint Mark's Throne, he began to put the foundations for a great monastery close to the remains of the old city. Today, the Monastery of Saint Mina is one of the most famous monasteries in Egypt. The relics of Saint Mina, as well as that of Pope Cyril VI of Alexandria lie in this monastery. The cathedral of Saint Mina was destroyed during the Arab invasions of the 7th century.

El Alamein battle

According to orthodox Christian belief, in June 1942, during the North-Africa campaign that was decisive for the outcome of the Second World War, the German forces under the command of General Rommel were on their way to Alexandria, and happened to make a halt near a place which the Arabs call El Alamein. An ancient ruined church nearby in Abu Mena was dedicated to Saint Menas; there some people say he is buried. Here the weaker Allied forces, including some Greeks, confronted the numerically and militarily superior German army, and the result of the coming battle of El Alamein seemed certain. During the first night of engagement, at midnight, Saint Menas came out of his ruined church and appeared in the midst of the German camp at the head of a caravan of camels, exactly as he was shown on the walls of the ruined church in one of the frescoes depicting his miracles. This astounding and terrifying apparition so undermined German morale that it contributed to the brilliant victory of the Allies. Winston Churchill said of this victory: "Now this is not the end. It is not even the beginning of the end, but it is, perhaps, the end of the beginning." He also wrote: "Before Alamein we never had a victory. After Alamein, we never had a defeat.[12][13][14][15]

See also

References

- https://www.goarch.org/chapel/saints?contentid=285

- "Martyr Menas of Egypt". oca.org. Retrieved 2018-03-17.

- "Saint Menas". www.digitalegypt.ucl.ac.uk. Retrieved 2018-03-17.

- Menas the Miracle Worker, Saint – Claremont Coptic Encyclopedia

- "St. Menas". www.copticchurch.net. Retrieved 2018-03-17.

- "Catholic Encyclopedia: St. Menas". www.newadvent.org. Retrieved 2018-03-17.

- "Saint Mina Coptic Orthodox Church". 2007-10-06. Archived from the original on 2007-10-06. Retrieved 2018-03-17.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- "Saint Menas – Saints and Martyrs– Treasures of Heaven". www.learn.columbia.edu. Retrieved 2018-03-17.

- Grossmann, Peter (1998). "The Pilgrimage Center of Abû Mînâ". in D. Frankfurter (ed.), Pilgrimage & Holy Space in Late Antique Egypt. Leiden-Boston-Köln, Brill: p. 282

- "Ampullae". www.stmina-monastery.org. Retrieved 2018-03-17.

- "Menas", Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium, (Alexander Kazhdan, ed.), New York: Oxford University Press, p. 1339

- "The Miracle of Saint Menas in El Alamein in 1942". www.johnsanidopoulos.com. Retrieved 2018-03-17.

- "A warrior saint for Veteran's Day – This Side of Glory". This Side of Glory. 2012-11-12. Retrieved 2018-03-17.

- "El Alamein – Revealing the Secret Turning Point of World War II". www.godlikeproductions.com. Retrieved 2018-03-17.

- The Great Egyptian and Coptic Martyr – St Mina Monastery

Further reading

- Weitzmann, Kurt, ed., Age of spirituality: late antique and early Christian art, third to seventh century, pp. 573–578, 1979, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, ISBN 9780870991790

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Saint Menas. |