Süleymaniye Mosque

The Süleymaniye Mosque (Turkish: Süleymaniye Camii, Turkish pronunciation: [sylejˈmaːnije]) is an Ottoman imperial mosque located on the Third Hill of Istanbul, Turkey. The mosque was commissioned by Suleiman the Magnificent and designed by the imperial architect Mimar Sinan. An inscription specifies the foundation date as 1550 and the inauguration date as 1557. Behind the qibla wall of the mosque is an enclosure containing the separate octagonal mausoleums of Suleiman the Magnificent and that of his wife Hurrem Sultan (Roxelana). The Süleymaniye Mosque is the second largest mosque in the city, and one of the best-known sights of Istanbul.

| Süleymaniye Mosque | |

|---|---|

View of the mosque from Galata Tower | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Sunni Islam |

| Location | |

| Location | Istanbul, Turkey |

Location in the Fatih district of Istanbul | |

| Geographic coordinates | 41°00′58″N 28°57′50″E |

| Architecture | |

| Architect(s) | Mimar Sinan |

| Type | Mosque |

| Style | Ottoman architecture |

| Groundbreaking | 1550 |

| Completed | 1557 |

| Specifications | |

| Height (max) | 53 m (174 ft) |

| Dome dia. (inner) | 26 m (85 ft) |

| Minaret(s) | 4 |

| Minaret height | 76 m (249 ft) |

| Part of | Historic Areas of Istanbul |

| Criteria | Cultural: i, ii, iii, iv |

| Reference | 356 |

| Inscription | 1985 (9th session) |

History

The Süleymaniye Mosque, was built on the order of Sultan Süleyman (Süleyman the Magnificent), and designed by the imperial architect Mimar Sinan. The Arabic foundation inscription above the north portal of the mosque is carved in thuluth script on three marble panels. It gives a foundation date of 1550 and an inauguration date of 1557. In reality the planning of the mosque began before 1550 and parts of the complex were not completed until after 1557.[1]

The design of the Süleymaniye also plays on Suleyman's self-conscious representation of himself as a 'second Solomon.' It references the Dome of the Rock, which was built on the site of the Temple of Solomon, as well as Justinian's boast upon the completion of the Hagia Sophia: "Solomon, I have surpassed thee!"[2] The Süleymaniye, similar in magnificence to the preceding structures, asserts Suleyman's historical importance. The structure is nevertheless smaller in size than its older archetype, the Hagia Sophia.

The Süleymaniye was damaged in the great fire of 1660 and was restored by Sultan Mehmed IV.[3] Part of the dome collapsed during the earthquake of 1766. Subsequent repairs damaged what was left of the original decoration of Sinan (recent cleaning has shown that Sinan experimented first with blue, before making red the dominant color of the dome).[4]

During World War I the courtyard was used as a weapons depot, and when some of the ammunition ignited, the mosque suffered another fire. Not until 1956 was it fully restored again.

The construction of the Haliç Metro Bridge in 2013 has irreparably altered the view of the mosque from north.[5]

Architecture

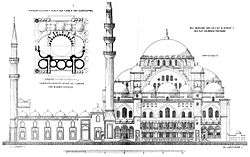

Exterior

Like the other imperial mosques in Istanbul, the entrance to the mosque itself is preceded by a forecourt with a central fountain. The courtyard is of exceptional grandeur with a colonnaded peristyle with columns of marble, granite and porphyry. The northwest facade of the mosque is decorated with rectangular Iznik tile window lunettes.[6] The mosque is the first building where the Iznik tiles include the brightly coloured tomato red clay under the glaze.[7]

At the four corners of the courtyard are the four minarets. The two taller minarets have three galleries (serifes) and rise to a high of 63.8 m (209 ft) without their lead caps and 76 m (249 ft) including the caps.[8] Four minarets were used for mosques endowed by a sultan (princes and princesses could construct two minarets; others only one). The minarets have a total of 10 galleries, which by tradition indicates that Suleiman I was the 10th Ottoman sultan.[9]

The main dome is 53 metres (174 feet) high and has a diameter of 26.5 metres (86.9 feet) which is exactly half the height.[10] At the time it was built, the dome was the highest in the Ottoman Empire, when measured from sea level, but still lower from its base and smaller in diameter than that of Hagia Sophia.

Interior

The interior of the mosque is almost a square, 59 metres (194 feet) in length and 58 metres (190 feet) in width, forming a single vast space. The dome is flanked by semi-domes, and to the north and south arches with tympana-filled windows, supported by enormous porphyry monoliths. Sinan decided to make a radical architectural innovation to mask the huge north-south buttresses needed to support these central piers. He incorporated the buttresses into the walls of the building, with half projecting inside and half projecting outside, and then hid the projections by building colonnaded galleries. There is a single gallery inside the structure, and a two-story gallery outside.

The interior decoration is restrained with stained-glass windows restricted to the qibla wall. Iznik tile revetments are only used around the mihrab.[11] The repeating rectangular tiles have a stencil-like floral pattern on a white ground. The flowers are mainly blue with turquoise, red and black but green is not used.[12] On either side of the mihrab are large Iznik tile calligraphic roundels with text from the Al-Fatiha surah of the Quran (1:1–7).[13][14] The white marble mihrab and mimbar are also simple in design, and woodwork is restrained, with simple designs in ivory and mother of pearl.

Mausoleums

In the walled enclosure behind the qibla wall of the mosque are the separate mausoleums (türbe) of Sultan Suleiman I and his wife Hurrem Sultan (Roxelana). Hurrem Sultan's octagonal mausoleum is dated 1558, the year of her death.[15] The 16 sided interior is decorated with Iznik tiles. The seven rectangular windows are surmounted by tiled lunettes and epigraphic panels. Between the windows are eight mihrab-like hooded niches.[16] The ceiling is now whitewashed but was probably once painted in bright colours.[17]

The much larger octagonal mausoleum of Suleiman the Magnificent bears the date of 1566, the year of his death, but it was probably not completed until the following year. The mausoleum is surrounded by a peristyle with a roof supported by 24 columns and has the entrance facing east rather than the usual north.[18] Under the portico on either side of the entrance are Iznik tiled panels.[16] These are the earliest tiles that are decorated with the bright emerald green colour that would become a common feature of Iznik ceramics.[19] The interior has a false dome supported on eight columns within the outer shell. There are 14 windows set at ground level and an additional 24 windows with stained glass set in the tympana under the arches. The walls and the pendentives are covered with polychrome Iznik tiles. Around the room above the windows is a band of inscriptive tiled panels.[17] The text quotes the Throne verse and the following two verses from the Quran (2:255-58).[16][20] In addition to the tomb of Suleiman the Magnificent, the mausoleum houses the tombs of his daughter Mihrimah Sultan and those of two later sultans: Suleiman II (ruled 1687–1691) and Ahmed II (ruled 1691–1695).[17][21]

Complex

As with other imperial mosques in Istanbul, the Süleymaniye Mosque was designed as a külliye, or complex with adjacent structures to service both religious and cultural needs. The original complex consisted of the mosque itself, a hospital (darüşşifa), primary school, public baths (hamam), a caravanserai, four Qur'an schools (medrese), a specialized school for the learning of hadith, a medical college, and a public kitchen (imaret) which served food to the poor. Many of these structures are still in existence, and the former imaret is now a noted restaurant. The former hospital is now a printing factory owned by the Turkish Army.

Just outside the mosque walls, to the north is the tomb of architect Sinan.[22] It was completely restored in 1922.[23]

Gallery

.jpg)

Süleymaniye Mosque window

Süleymaniye Mosque window

.jpg)

.jpg)

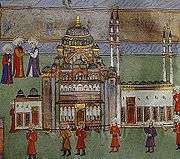

An Ottoman miniature of the Mosque

An Ottoman miniature of the Mosque Süleymaniye Mosque, 1890

Süleymaniye Mosque, 1890 Exterior aerial shot of Süleymaniye Mosque, 1903. Brooklyn Museum Archives, Goodyear Archival Collection

Exterior aerial shot of Süleymaniye Mosque, 1903. Brooklyn Museum Archives, Goodyear Archival Collection Suleiman's mausoleum

Suleiman's mausoleum Mausoleum of Hurrem Sultan (Roxelana)

Mausoleum of Hurrem Sultan (Roxelana) Hurrem's Mausoleum

Hurrem's Mausoleum Süleymaniye Mosque entrance to garden from west

Süleymaniye Mosque entrance to garden from west Süleymaniye Mosque western portal

Süleymaniye Mosque western portal Istanbul Süleymaniye Mosque 2015 1330

Istanbul Süleymaniye Mosque 2015 1330 Süleymaniye Mosque detail

Süleymaniye Mosque detail Süleymaniye Mosque from north side

Süleymaniye Mosque from north side Süleymaniye Mosque view from south side

Süleymaniye Mosque view from south side Süleymaniye Mosque domes from outside

Süleymaniye Mosque domes from outside Süleymaniye Mosque domes

Süleymaniye Mosque domes Süleymaniye Mosque domes

Süleymaniye Mosque domes Süleymaniye Mosque muezzin mahfili

Süleymaniye Mosque muezzin mahfili Süleymaniye Mosque during service

Süleymaniye Mosque during service

See also

- List of Friday mosques designed by Mimar Sinan

- Suleymaniye hamam

- List of mosques in Istanbul

References

- Necipoğlu 2005, p. 208.

- Neci̇poğlu-Kafadar 1985, p. 103.

- Baer 2004.

- Goodwin 2003, p. 235.

- Hartmann, Veronika. "Wem gehört die Stadt?". NZZ. Retrieved 6 July 2013.

- Necipoğlu 2005, p. 217.

- Denny 2004, p. 79.

- Goodwin 2003, p. 226.

- Neci̇poğlu-Kafadar 1985, pp. 105-106.

- Goodwin 2003, p. 231.

- Necipoğlu 2005, p. 216.

- Denny 2004, pp. 86, 209.

- Necipoğlu 2005, p. 219 fig 183.

- Quran 1:1–7

- Goodwin 2003, p. 237.

- Necipoğlu 2005, p. 220.

- Goodwin 2003, p. 238.

- Goodwin 2003, pp. 237-238.

- Atasoy & Raby 1989, p. 230.

- Quran 2:255–258

- Sumner-Boyd & Freely 2010, p. 202.

- Necipoğlu 2005, pp. 150, 205 Fig. 167 (13).

- Goodwin 2003, p. 222.

Sources

- Atasoy, Nurhan; Raby, Julian (1989). Petsopoulos, Yanni (ed.). Iznik: The Pottery of Ottoman Turkey. London: Alexandria Press. ISBN 978-1-85669-054-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Baer, Marc David (2004). "The great fire of 1660 and the Islamization of Christian and Jewish space in Istanbul". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 36 (2): 159–181. JSTOR 3880030.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Denny, Walter B. (2004). Iznik: the Artistry of Ottoman Ceramics. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-51192-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Goodwin, Godfrey (2003) [1971]. A History of Ottoman Architecture. London: Thames & Hudson. pp. 215–239. ISBN 978-0-500-51192-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Neci̇poğlu-Kafadar, Gülru (1985). "The Süleymaniye Complex in Istanbul: an interpretation". Muqarnas. 3: 92–117. doi:10.2307/1523086. JSTOR 1523086.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Necipoğlu, Gülru (2005). The Age of Sinan: Architectural Culture in the Ottoman Empire. London: Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-1-86189-253-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sumner-Boyd, Hilary; Freely, John (2010). Strolling through Istanbul. London: Tauris Parke. pp. 199–208. ISBN 978-1-84885-154-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Barkan, Ömer Lûtfi (1972–1979). Süleymaniye Cami ve İmareti İnşaatı (1550-1557) (in Turkish). (2 Volumes). Ankara: Türk Tarih Kurumu Basımevi. OCLC 614354340.

- Faroqhi, Suraiyah (2005). Subjects of the Sultan: Culture and Daily Life in the Ottoman Empire. London: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 1-85043-760-2.

- Kolay, İlknur Aktuğ; Çeli̇k, Serpi̇l (2006). "Ottoman stone acquisition in the mid-sixteenth century: the Süleymani̇ye Complex in Istanbul". Muqarnas. 23: 251–272. JSTOR 25482444.

- Morkoç, Selen B. (2008). "Reading architecture from the text: the Ottoman story of the four marble columns". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 67: 31–47. doi:10.1086/586669.

- Rogers, J.M. (2007). Sinan: Makers of Islamic Civilization. London: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 1-84511-096-X.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

- Süleymaniye Külliyesi, Archnet

- Süleymaniye Mosque ve Mimar Sinan (in Turkish)

- Suleymaniye Mosque Virtual Walking Tour, Saudi Aramco World.

- Photographs by Dick Osseman