Şehzade Mosque

The Şehzade Mosque (Turkish: Şehzade Camii, from the original Persian شاهزاده Šāhzādeh, meaning "prince") is a 16th-century Ottoman imperial mosque located in the district of Fatih, on the third hill of Istanbul, Turkey. It was commissioned by Suleiman the Magnificent as a memorial to his son Şehzade Mehmed who died in 1543. It is sometimes referred to as the "Prince's Mosque" in English.[1] In a June 2016 attack, the windows of the mosque were shattered.

| Şehzade Mosque | |

|---|---|

Şehzade Mosque | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Sunni Islam |

| Location | |

| Location | Istanbul, Turkey |

Location within the Fatih district of Istanbul | |

| Geographic coordinates | 41°00′49.7″N 28°57′25.8″E |

| Architecture | |

| Architect(s) | Mimar Sinan |

| Type | Mosque |

| Groundbreaking | 1543 |

| Completed | 1548 |

| Specifications | |

| Dome height (outer) | 37 meters (121 ft) |

| Dome dia. (inner) | 19 meters (62 ft) |

| Minaret(s) | 2 |

| Minaret height | 55 meters (180 ft) |

| Materials | cut stone, granite, marble |

History

The construction of the Şehzade Complex (külliye) was ordered by the Ottoman Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent as a memorial to his favorite son Şehzade Mehmed (born 1521) who died in 1543 while returning to Istanbul after a victorious military campaign in Hungary.[2] Mehmed was the eldest son of Suleiman's only legal wife Hürrem Sultan - although not his eldest son - and before his untimely death he was primed to accept the sultanate following Suleiman's reign. Suleiman is said to have personally mourned the death of Mehmed for forty days at his temporary tomb in Istanbul, the site upon which the imperial architect Mimar Sinan would construct a lavish mausoleum to Mehmed as one part of a larger mosque complex dedicated to the princely heir. The complex was Sinan's first important imperial commission and ultimately one of his most ambitious architectural works, even though it was designed early in his long career.

Architecture

Exterior

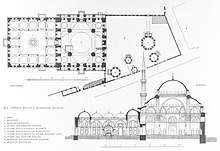

The mosque is entered through a marble-paved colonnaded forecourt with an area equal to that of the mosque itself.[3] The courtyard is bordered by a portico with five domed bays on each side, with arches in alternating pink and white marble. At the center is an ablution fountain (şadırvan), which was a later donation from Sultan Murat IV. The twin minarets have two galleries and elaborate geometric sculpture in low bas-relief and occasional terracotta inlays. It is the only non-sultanic mosque designed by Sinan with a pair of minarets with two galleries.[4]

The mosque itself has a square plan, covered by a central dome, flanked by four half-domes. The dome is supported by four piers, and has a diameter of 19 metres (62 ft) and a height of 37 metres (121 ft). It was in this building that Sinan first adopted the technique of placing colonnaded galleries along the entire length of the north and south facades in order to conceal the buttresses.

Interior

The interior of the Şehzade Mosque has a symmetrical plan, with the area under the central dome expanded by use of four semi-domes, one on each side, in the shape of a four leaf clover. This technique was not entirely successful, as it isolated the four huge piers needed to support the central dome, and was never again repeated by Sinan. The interior of the mosque has a very simple design, without galleries.

Complex

Şehzade complex (külliye) is situated between Fatih and Bayezid complexes. The complex consists of the mosque, the mausoleum or türbe of Prince Mehmet (which was completed prior to the mosque), two Qur'an schools (medrese), a public kitchen (imaret) which served food to the poor, and a caravansarai. The mosque and its courtyard are surrounded by a wall that separates them from the rest of the complex.

Mausoleums

There are five mausoleums (türbe) in the funerary garden to the south of the mosque. The earliest and largest is that of Şehzade Mehmed which has a Persian foundation inscription over the entrance with a date of 1543–44.[5] The mausoleum is an octagonal structure, with a fluted dome, polychrome stonework and a triple-arched portico. The interior walls are covered with multi-coloured cuerda seca tiles and the windows have stained glass.[6][lower-alpha 1] An unusual feature is the rectangular wooden throne over Mehmed's sarcophagus which symbolized his status as the heir apparent. Within the mausoleum there are also the tombs of Mehmed's daughter Hümaşah Sultan and his youngest brother Şehzade Cihangir (d. 1553). The identity of the fourth sarcophagus in not known.[10]

To the south of the Şehzade mausoleum is the smaller octagonal türbe of Grand Vizier Rüstem Pasha, which was also designed by Sinan. The inscription gives the year as AH 968 (1560–61). Rüstem Pasha was the husband of Mihrimah, the daughter of Suleiman the Magnificent. Like the Rüstem Pasha Mosque it is decorated with a large number of underglazed Iznik tiles.[11][12] By the gate to the complex is the türbe of Grand Vizier Ibrahim Pasha, son-in-law of Murat III, who died in 1603.[13] The türbe was designed by Dalgıç Ahmed Çavuş, and almost equals that of Şehzade in design and use of tiled decoration.

Gallery

Shezade mosque view with türbe's domes

Shezade mosque view with türbe's domes Shezade mosque view from north-east side

Shezade mosque view from north-east side Shezade mosque view from surrounding park, north side

Shezade mosque view from surrounding park, north side Shezade mosque courtyard

Shezade mosque courtyard Shezade mosque general view interior

Shezade mosque general view interior Shezade mosque view interior towards mihrab

Shezade mosque view interior towards mihrab Shezade mosque side of a main column

Shezade mosque side of a main column Shezade mosque domes

Shezade mosque domes Shezade mosque above entrance

Shezade mosque above entrance Shezade mosque details of minaret

Shezade mosque details of minaret

Notes

- Godfrey Goodwin in his book A History of Ottoman Architecture published in 1971 states that the cuerda seca tiles decorating the mausoleum were made in Iznik.[7] From surviving account books the historian Gülru Necipoğlu has shown that the Ottoman court employed a team of tilemakers in Istanbul and it is now generally assumed that all cuerda seca tiles on imperial buildings dating from the first half of the 16th century were manufactured in Istanbul rather than Iznik.[8][9]

References

- Rogers, Sinan, pp. index

- Necipoğlu 2005, pp. 191-192.

- Necipoğlu 2005, p. 196.

- Necipoğlu 2005, p. 121.

- Necipoğlu 2005, p. 193.

- Necipoğlu 2005, p. 198.

- Goodwin 2003, p. 211.

- Necipoğlu 1990.

- Carswell 2006, pp. 57-58.

- Necipoğlu 2005, p. 200.

- Necipoğlu 2005, p. 327, figs 314-315.

- Goodwin 2003, p. 252.

- Necipoğlu 2005, p. 531, Note 56.

Sources

- Carswell, John (2006) [1998]. Iznik Pottery. London: British Museum Press. ISBN 978-0-7141-2441-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Necipoğlu, Gülru (1990). "From International Timurid to Ottoman: a change of taste in sixteenth-century ceramic tiles". Muqarnas. 7: 136-170. JSTOR 1523126.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Necipoğlu, Gülru (2005). The Age of Sinan: Architectural Culture in the Ottoman Empire. London: Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-1-86189-253-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Goodwin, Godfrey (2003) [1971]. A History of Ottoman Architecture. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-51192-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Aptullah Kuran: Sinan: The grand old master of Ottoman architecture, Ada Press Publishers, 1987. ISBN 0-941469-00-X (in English)

- Faroqhi, Suraiyah (2005). Subjects of the Sultan: Culture and Daily Life in the Ottoman Empire. I B Tauris. ISBN 1-85043-760-2.

- Freely, John (2000). Blue Guide Istanbul. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-32014-6.

- Rogers, J.M. (2007). Sinan: Makers of Islamic Civilization. I B Tauris. ISBN 1-84511-096-X.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Şehzade Mosque. |