Ruble

The ruble or rouble (/ˈruːbəl/; Russian: рубль, IPA: [rublʲ]) is or was a currency unit of a number of countries in Eastern Europe closely associated with the economy of Russia. Originally, the ruble was the currency unit of Imperial Russia and then the Soviet Union (as the Soviet ruble). As of 2020 it is the currency unit of Russia (as the Russian ruble), Belarus (as the Belarussian ruble) and Transnistria (as the Transnistrian ruble). The Russian ruble is also used in two regions of Georgia, the partially recognised states (including by Russia) Abkhazia and South Ossetia. In the past, several other countries influenced by Russia and the Soviet Union had currency units that were also named rubles.

_front.jpg)

The Russian rubles (![]()

Etymology

Origins

According to one version, the word "ruble" is derived from the Russian verb рубить (rubit), "to cut, to chop, to hack", as a ruble was considered a cutout piece of a silver grivna.

Rubles were parts of the grivna or pieces of silver with notches indicating their weight. Each grivna was divided into four parts; the name "ruble" came from the word "cut" because the silver rod weighing 1 grivna was split into four parts, which were called rubles.[1]

Others say the ruble was never part of a grivna but a synonym for it. This is attested in a 13th century Novgorod birch bark manuscript, where both ruble and grivna referred to 204 gramms (6.6 troy ounces) of silver.[2] The casting of these pieces included some sort of cutting (the exact technology is unknown), hence the name from рубить (rubit).[3][4]

Another version of the word's origin is that it comes from the Russian noun рубец (rubets), the seam that is left around a silver bullions after casting: silver was added to the cast in two steps. Therefore, the word ruble means "a cast with a seam".[5] A popular theory deriving the word ruble from rupee is probably not correct.[6]

The ruble was the Russian equivalent of the mark, a measurement of weight for silver and gold used in medieval Western Europe. The weight of one ruble was equal to the weight of one grivna.

In Russian, a folk name for ruble, tselkovyj (целко́вый, IPA: [tsɨlˈkovɨj], wholesome), is known, which is a shortening of the целковый рубль ("tselkovyj ruble"), i.e., a wholesome, uncut ruble. This name persists in the Mordvin word for ruble, целковой.

Since the monetary reform of 1534, one Russian accounting ruble became equivalent to 100 silver Novgorod denga coins or smaller 200 Muscovite denga coins or even smaller 400 polushka coins. Exactly the former coin with a rider on it soon became colloquially known as kopek and was the higher coin until the beginning of the 18th century. Ruble coins as such did not exist till Peter the Great, when in 1704 he reformed the old monetary system and ordered mintage of a 28-gramme silver ruble coin equivalent to 100 new copper kopek coins. Apart from one ruble and one kopek coins other smaller and greater coins existed as well.

English spelling

Both the spellings ruble and rouble are used in English. The form rouble is preferred by the Oxford English Dictionary, but the earliest use recorded in English is the now completely obsolete robble. The form rouble probably derives from the transliteration into French used among the Tsarist aristocracy. There are two main usage tendencies: one is for North American authors to use ruble and other English speakers to use rouble, while the other is for older sources to use rouble and more recent ones to use ruble. Neither tendency is absolutely consistent, and there is also the obvious danger of confusion with rubble.

The Russian plurals that may be seen on the actual currency are modified according to Russian grammar. Numbers ending in 1 (except for 11) are followed by nominative singular рубль rubl′, копе́йка kopéyka. Numbers ending in 2, 3 or 4 (except for 12–14) are followed by genitive singular рубля́ rublyá, копе́йки kopéyki. Numbers ending in 5–9, 0, or 11–14 are followed by genitive plural рубле́й rubléy, копе́ек kopéyek.

Other languages

In several languages spoken in Russia and the former Soviet Union, the currency name has no etymological relation with ruble. Especially in Turkic languages or languages influenced by them, the ruble is often known (also officially) as som or sum (meaning pure), or manat (from Russian moneta, meaning coin). Soviet banknotes had their value printed in the languages of all 15 republics of the Soviet Union.

History

Imperial ruble (14th century – 1917)

From the 14th to the 17th centuries the ruble was neither a coin nor a currency but rather a unit of weight. The most used currency was a small silver coin called denga (pl. dengi). There were two variants of the denga minted in Novgorod and Moscow. The weight of a denga silver coin was unstable and inflating, but by 1535 one Novgorod denga weighted 0.68 grams (0.022 troy ounces), the Moscow denga being a half of the Novgorod denga. Thus one account ruble consisted of 100 Novgorod or 200 Moscow dengi (68 g (2.2 ozt) of silver). As the Novgorod denga bore the image of a rider with a spear (Russian: копьё, kop’yo), it later has become known as kopek. In the 17th century the weight of a kopek coin lowered to 0.48 g (0.015 ozt), thus one ruble was equal to 48 g (1.5 ozt) of silver.[2][3]

In 1654–1655 tsar Alexis I tried to carry out a monetary reform and ordered to mint silver one ruble coins from imported joachimsthalers and new kopek coins from copper (old silver kopeks was left in circulation). Although around 1 million of such rubles was made, its lower weight (28–32 grams) against the nominal ruble (48 g) led to counterfeit, speculation and inflation, and after the Copper Riot of 1662 the new monetary system was abandoned in favour of the old one.[2][3]

Russian Empire

In 1704 Peter the Great finally reformed the old Russian monetary system, ordering the minting of a 28 g (0.99 oz) silver ruble coin equivalent to 100 new copper kopek coins, thus making the Russian ruble the world's first decimal currency.[2]

The amount of precious metal in a ruble varied over time. In a 1704 currency reform, Peter the Great standardized the ruble to 28 grams of silver. While ruble coins were silver, there were higher denominations minted of gold and platinum. By the end of the 18th century, the ruble was set to 4 zolotnik 21 dolya (almost exactly equal to 18 grams) of pure silver or 27 dolya (almost exactly equal to 1.2 grams) of pure gold, with a ratio of 15:1 for the values of the two metals. In 1828, platinum coins were introduced with 1 ruble equal to 77⅔ dolya (3.451 grams).

On 17 December 1885, a new standard was adopted which did not change the silver ruble but reduced the gold content to 1.161 grams, pegging the gold ruble to the French franc at a rate of 1 ruble = 4 francs. This rate was revised in 1897 to 1 ruble = 2⅔ francs (0.774 grams gold).

The ruble was worth about 0.50 USD in 1914.[7][8]

With the outbreak of World War I, the gold standard peg was dropped and the ruble fell in value, suffering from hyperinflation in the early 1920s. With the founding of the Soviet Union in 1922, the Russian ruble was replaced by the Soviet ruble. The pre-revolutionary Chervonetz was temporarily brought back into circulation from 1922–1925.[9]

Russia's Coins

By the beginning of the 19th century, copper coins were issued for 1⁄4, 1⁄2, 1, 2 and 5 kopeks, with silver 5, 10, 25 and 50 kopeks and 1 ruble and gold 5 although production of the 10 ruble coin ceased in 1806. Silver 20 kopeks were introduced in 1820, followed by copper 10 kopeks minted between 1830 and 1839, and copper 3 kopeks introduced in 1840. Between 1828 and 1845, platinum 3, 6 and 12 rubles were issued. In 1860, silver 15 kopeks were introduced, due to the use of this denomination (equal to 1 złoty) in Poland, whilst, in 1869, gold 3 rubles were introduced.[11] In 1886, a new gold coinage was introduced consisting of 5 and 10 ruble coins. This was followed by another in 1897. In addition to smaller 5 and 10 ruble coins, 7 1⁄2 and 15 ruble coins were issued for a single year, as these were equal in size to the previous 5 and 10 ruble coins. The gold coinage was suspended in 1911, with the other denominations produced until the First World War.

Constantine ruble

The Constantine ruble (Russian: константиновский рубль, konstantinovsky rubl′) is a rare silver coin of the Russian Empire bearing the profile of Constantine, the brother of emperors Alexander I and Nicholas I. Its manufacture was being prepared at the Saint Petersburg Mint during the brief Interregnum of 1825, but it was never minted in numbers, and never circulated in public. Its existence became known in 1857 in foreign publications.[12]

Banknotes

Imperial issues

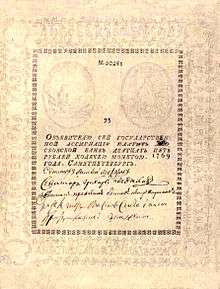

In 1768, during the reign of Catherine the Great, the Assignation Bank was instituted to issue the government paper money. It opened in Saint Petersburg and in Moscow in 1769.

In 1769, Assignation rubles were introduced for 25, 50, 75 and 100 rubles, with 5 and 10 rubles added in 1787 and 200 ruble in 1819. The value of the Assignation rubles fell relative to the coins until, in 1839, the relationship was fixed at 1 coin ruble = 3½ assignat rubles. In 1840, the State Commercial Bank issued 3, 5, 10, 25, 50 and 100 rubles notes, followed by 50 ruble credit notes of the Custody Treasury and State Loan Bank.

In 1843, the Assignation Bank ceased operations, and state credit notes (Russian: государственные кредитные билеты, gosudarstvenniye kreditniye bilety) were introduced in denominations of 1, 3, 5, 10, 25, 50 and 100 rubles. In 1859 a paper credit ruble was worth about nine tenths of a silver ruble [13] These circulated, in various types, until the revolution, with 500 rubles notes added in 1898 and 250 and 1000 rubles notes added in 1917. In 1915, two kinds of small change notes were issued. One, issued by the Treasury, consisted of regular style (if small) notes for 1, 2, 3, 5 and 50 kopeks. The other consisted of the designs of stamps printed onto card with text and the imperial eagle printed on the reverse. These were in denominations of 1, 2, 3, 10, 15 and 20 kopeks.

Provisional Government issues

In 1917, the Provisional Government issued treasury notes for 20 and 40 rubles. These notes are known as "Kerenski" or "Kerensky rubles". The provisional government also had 25 and 1,000 rubles state credit notes printed in the United States but most were not issued.

Provisional Government

The Russian Provisional Government (Russian: Временное правительство России, tr. Vremennoye pravitel'stvo Rossii) was a provisional government of Russia established immediately following the abdication of Tsar Nicholas II of the Russian Empire on 2 March [15 March, New Style] 1917.[1][2] The intention of the provisional government was the organization of elections to the Russian Constituent Assembly and its convention. The provisional government lasted approximately eight months, and ceased to exist when the Bolsheviks gained power after the October Revolution in October [November, N.S.] 1917.

Soviet ruble (1917–1992)

The Soviet ruble replaced the ruble of the Russian Empire. The Soviet ruble (code: SUR) was the currency of the Soviet Union between 1917 and the breakup of the Soviet Union in 1991. The Soviet ruble was issued by the State Bank of the USSR. The Soviet ruble continued to be used in the 15 Post-Soviet states.

The Soviet ruble was used until 1992 in Russia (replaced by Russian ruble), Ukraine (replaced by Ukrainian karbovanets), Estonia (replaced by Estonian kroon), Latvia (replaced by Latvian rublis), Lithuania (replaced by Lithuanian talonas), and until 1993 in Belarus (replaced by Belarusian ruble), Georgia (replaced by Georgian lari), Armenia (replaced by Armenian dram), Kazakhstan (replaced by Kazakhstani tenge), Kyrgyzstan (replaced by Kyrgyzstani som), Moldova (replaced by Moldovan cupon), Turkmenistan (replaced by Turkmenistan manat), Uzbekistan (replaced by Uzbekistani so'm), and until 1994 in Azerbaijan (replaced by Azerbaijani manat) and until 1995 in Tajikistan (replaced by Tajikistani ruble). [14]

Symbol

The Ruble sign “₽” is a currency sign used to represent the monetary unit of account in Russia. It features a sans-serif Cyrillic letter Р (R in the English alphabet) with an additional horizontal stroke.

References

- Кондратьев И. К. Седая старина Москвы. М., 1893. In Russian: Рубли были частями гривны или кусками серебра с зарубками, означавшими их вес. Каждая гривна разделялась на четыре части; название же рубль произошло от слова «рубить», потому что прут серебра в гривну весом разрубался на четыре части, которые и назывались рублями.

- Kamentseva, E.; Ustyugov, N. (1975). Russkaya metrologiya Русская метрология (in Russian).

- Spassky, I. G. (1970). Russkaya monetnaya sistema Русская монетная система (in Russian). Leningrad.

- Vasmer, Max (1986–1987) [1950–1958]. "Рубль". In Trubachyov, O. N.; Larin, B. O. (eds.). Этимологический словарь русского языка [Russisches etymologisches Wörterbuch] (in Russian) (2nd ed.). Moscow: Progress.

- Sergey Khalatov. History of Ruble and Kopek on "Collectors' Portal UUU.RU" (in Russian)

- Vasmer, Max. "Рубль". Vasmer Etymological dictionary.

- "Gold and Silver Standards". Cyberussr.com. Retrieved 30 August 2015.

- "Calculate the value of $100000 in 1914 – Inflation on 100000 dollars". DollarTimes.com. Retrieved 30 August 2015.

- La Crise de la Monnaie Anglaise (1931), Catiforis S.J. Recueil Sirey, 1934, Paris

- Catherine II. Novodel Sestroretsk Rouble 1771, Heritage Auctions, retrieved 1 September 2015

- Peter Symes. "Currency of Three". Pjsymes.com.au. Retrieved 30 August 2015.

- By 1880 Russian numismatists were well aware of the existence of Constantine rubles, but their first printed description was published only in 1886 – Kalinin, p.1.

- Jerome Blum, The End of the Old Order in Rural Europe, 1978, p169

- Russian Provisional Government

External links

| Look up ruble or rouble in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Монеты России и СССР

- Historical Currency Converter Historical value of the ruble in other currencies