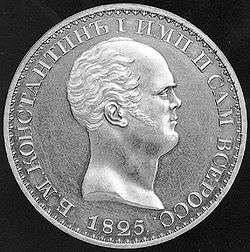

Constantine ruble

The Constantine ruble is a rare silver coin of the Russian Empire bearing the profile of Constantine, the brother of emperors Alexander I and Nicholas I. It was prepared to be manufactured at the Saint Petersburg Mint during the brief Interregnum of 1825 but has never been minted in numbers and never circulated in public. The fact of its existence, classified in Russia until 1886,[1] leaked into European press in 1857.

According to Ivan Spassky, there are eight genuine Constantine rubles of two different types. Five are proof coins complete with edge lettering. A hypothetical sixth coin of this type was probably minted in December 1825 and disappeared without trace. Three coins of the so-called Schubert ruble type have no edge lettering. They are, most likely, intermediate work-in-progress proofs illegally removed from the Mint.

Three Constantine rubles are currently preserved at the Hermitage Museum and the State Historical Museum in Russia and the Smithsonian Institution in the United States.[2] The Hermitage also possesses the three genuine sets of press dies, in different stages of completion, seventeen tin work-in-progress samples and Jacob Reichel's original design on parchment.[3] All other genuine Constantine rubles are in private collections outside of Russia.

The so-called Trubetskoy ruble is a fake Constantine ruble manufactured in the 1860s in Paris, a rare collectible in its own right. Two original Trubetskoy rubles are preserved at the Hermitage Museum and the Smithsonian Institution, the third is privately owned.

Description

Genuine Constantine rubles conform to the standard of silver ruble established in 1810: .833 millesimal fineness silver alloy, 35 mm diameter, 20.73 grams gross weight.[4] Pure silver content of the coin is prominently written on the reverse as 4 and 21/96 zolotniks; hallmark is pressed on the edge, in Cyrillic. The actually weighs 20.63 grams, the Historical Museum coin weighs 20.55 grams, but the Smithsonian coin weighs only 18.52 grams.[5] The Schubert rubles without edge lettering weigh 20.75 grams (Schubert ruble), 20.57 grams (Richter ruble) and 20.89 grams (Garschin-Fuchs ruble).[6] The fake Trubetskoy ruble in the Hermitage collection is the heaviest at 21.48 grams.[6]

Obverse and reverse patterns are aligned at 180 degrees (top of obverse matches bottom of reverse). Mass-produced rubles of the period usually had their obverse, reverse and edge lettering pressed in a single operation. The automated presses produced nearly perfect alignment of edge lettering relative to obverse and reverse surfaces. Constantine rubles, on the contrary, were literally hand made on simple manually operated presses from blanks with pre-pressed edge lettering. They all display varying degrees of alignment errors.

History

Background

Grand Duke Constantine, second son of Paul I, was heir presumptive to his reigning brother Alexander, who had no legitimate issue, until 1823. In 1821–1822 the Romanov brothers agreed that Constantine would step down from the order of succession in favor of Nicholas.[7] The informal arrangement was sealed by Alexander's secret manifest in 1823.[8] Neither Constantine[9] nor Nicholas[10] were made aware of its existence; the whole country sincerely believed that Constantine was the heir. Extreme secrecy made the Manifest unenforceable in real life. When the news of Alexander's death reached Saint Petersburg on December 9 [O.S. November 27] 1825, Nicholas duly pledged allegiance to Constantine before Alexander Golitsyn, one of three persons entrusted with keeping the secret, could reach the Winter Palace.[11] Golitsyn convened an emergency meeting of the State Council and presented the Manifest. Council members, now facing an unprecedented dynastic crisis, were unprepared to act as state authority and left the outcome to Nicholas, who reiterated his allegiance to Emperor Constantine.[12] Constantine, who did not intend to reign, temporarily became the Emperor of All Russias.

Production

Minister of Finance Georg von Cancrin was present at the State Council meeting of December 9, and thus aware of the unfolding dynastic crisis. Nevertheless, on December 17 [O.S. December 5] Cancrin authorized making and testing the presses for the Constantine ruble. On the same day he also instructed Saint Peterburg Mint to press an additional run of the medal that was struck in 1779 on the occasion of Constantine's birth.[13]

Saint Petersburg Mint received the instructions on the next day, December 18 [O.S. December 6]. Constantine's birth medals were pressed immediately and sent to Cancrin's orders; making of the dies took a whole week. The dies were sized to fit a manual press and could not be reused in automated mass production presses. Tradition held it that the Constantine ruble presses were designed and carved by Jacob Reichel (obverse) and Vladimir Alekseyev (reverse). According to Schukina, Reichel was certainly the author of the artwork, but each of three obverse press dies was carved by its own engraver. All three differ in craftsmanship quality and stage of completion.[14]

The Mint pressed two first proof samples on December 24 [O.S. December 12], when the Romanovs had already resolved the succession crisis in favor of Nicholas. Actual number of Constantine rubles is debated. According to Ivan Spassky, there were only five.[15] According to studies by Bartoshevich and Valentin Yanin, there were six Constantine rubles with proper edge lettering, and one of them was lost without trace. Yanin suggested that the sixth missing coin was appropriated by Cancrin himself. The three known coins without edge lettering (Schubert ruble, Richter ruble and Fuchs ruble) were, most likely, illegally retained by the Mint employees or their superiors.[16]

In the evening of December 25 [O.S. December 13] Nicholas declared himself emperor. On the next day Nicholas prevailed over the Decembrist revolt and took full control over the country. Cancrin ordered to halt all work on the Constantine ruble and declared the whole affair a state secret.[17] Two of three pairs of press dies were left incomplete; they, along with five proof coins, tin proof pressings and Reichel's original drawings, were locked in the vaults of the Ministry of Finance. Their existence remained strictly classified throughout the reign of Nicholas I.

Rediscovery

In 1857, when Nicholas and all men involved in pressing the Constantine rouble were already dead, general Fyodor Schubert (1789–1865) broke the silence and published a brief description of a Constantine ruble from his private collection.[18] Schubert wrote that his coin was a test sample that was sent to Constantine's approval during the interregnum, and that press dies were destroyed upon accession of Nicholas I. Schubert's coin lacked edge lettering.[18]

In 1866 Bernhard Karl von Koehne published his account of the coin's history; according to Koene, the whole affair was Reichel's private venture. Reichel, wrote Koehne, sent three coins to Warsaw and all three disappeared when Constantine's palace was looted during the November Uprising. Two samples left in Saint Petersburg were destroyed along with the presses.[19]

In 1873 prince Trubetskoy (1813–1889) challenged Koene's story and published a different explanation of the events. According to Trubetskoy, all five test samples were sent to Warsaw and ended up in the hands of an anonymous Polish plunderer who later emigrated to France. After his death Trubetskoy became his widow's agent; two or three coins were allegedly sold to an American collector and perished in a shipwreck, two remained in Trubetskoy's possession. Russian collectors contested Trubetskoy's account and suspected that the so-called Trubetskoy rubles were fake.[20] After World War II Valentin Yanin partially redeemed Trubetskoy: according to Yanin, the legendary shipment of samples to Warsaw was a coverup of Cancrin's invention, rather than Trubetskoy's own hoax.

In 1874 Afanasy Bychkov (1818–1899) reported a detailed description of two tin pressings of Constantine ruble from his collection. Bychkov's proofs, according to Valentin Yanin, were genuine work-in-progress samples retained by Cancrin. Their existence explains the difference between the number of tin proofs recorded in 1825 (nineteen) and in 1884 (seventeen). Yanin theorized that Bychkov could have inherited from Cancrin the hypothetical sixth Constantine ruble, and that it was resold in Europe in 1898.[16]

An 1880 publication by former Ministry of Finance executive D. F. Kobeko confirmed suspicions against Trubetskoy. According to Kobeko, the Ministry still possessed five silver Constantine rubles, three sets of press dies and nineteen tin samples.[20] It appeared that Schubert's ruble, which lacked edge relief, was a genuine 1825 pressing, but the number of such incomplete pressings and their whereabouts remained unknown. The public also remained unaware that a few months earlier, in 1879, Alexander II of Russia removed five genuine Constantine rubles from the vault.[21]

Their story was declassified in an 1886 publication by Grand Duke Georgy Mikhailovich, who owned one of genuine Constantine rubles.[3] Alexander II retained one coin for himself (it is now in possession of the State Historical Museum), donated another to the Hermitage Museum and passed the other three to his relatives: Alexander of Hesse, Georgy Mikhailovich and Sergey Alexandrovich. The three sets of presses and original artwork drawn by Reichel on parchment were donated to the Hermitage Museum in October 1884 after the Hermitage director Vasilchikov pleaded the new emperor Alexander III.[3]

Distribution and provenance

Another Constantine ruble without edge relief, the so-called Richter ruble, emerged during World War I. According to chief numismatist of the Hermitage Ivan Spassky (1904–1990), who examined the Richter ruble in 1962, it is most likely genuine (Spassky wrote that he coin matched the original press dies).[22] A third ruble of this type, the Garshin-Fuchs ruble, resurfaced in Germany in 1981 and is also considered genuine. This find brought the total number of existing Constantine rubles to eight.[15]

Two coins with edge relief are still in Russia, at the Hermitage in Saint Petersburg and the State Historical Museum in Moscow. All others, including the Schubert and Richter rubles, ended up overseas. The collection of Georgy Mikhailovich is now owned by the Smithsonian Institution,[2] others are privately owned. Auction prices for genuine Constantine rubles rose from US$41,000 in 1964 to $200,000 in 1974 but in 1981 plummeted to $51,000.[23] One of Schubert rubles was resold in 2004 for $525,000. The auction company claimed that it was then the highest price record for a non-US coin.[24]

Ivan Spassky summarized his provenance studies, published posthumously in 1991, as:

| Type | Individual name (Spassky) | Weight (grams) | Circumstances of rediscovery | Last known owner (as of 1990) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proof coinage with edge lettering |

Hermitage ruble | 20.63 | Delivered from the Ministry of Finance to the Hermitage June 19, 1879.[5] | Hermitage Museum |

| Alexander II ruble | 20.55 | Delivered from the Ministry of Finance to Alexander II June 15, 1879. Transferred to the Hermitage in 1926 and from there to State Historical Museum in 1930.[5] | State Historical Museum | |

| Georgy Mikhailovich ruble | 18.52 | Presented to Grand Duke George Mikhailovich in 1879. Deposited in the Russian Museum in 1909. During the Russian Civil War the whole collection was moved out of the country and resurfaced in Yugoslavia. Repossessed by Princess Maria of Greece and Denmark, mother of Georgy, through court order. After her death one of her daughters moved the collection to the United States. Willis du Pont purchased the coin in 1959 and donated it to the Smithsonian Institution.[2][5][25] | Smithsonian Institution | |

| Sergei Alexandrovich ruble | Unknown | Presented to Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich in 1879 or 1880. Presumably the coin was auctioned at Hamburger's in 1898 and at Schulman's (New York) in 1965.[26] | Unknown | |

| Alexander von Hesse ruble | 20.61 | Presented to Prince Alexander of Hesse in February 1880. Auctioned in Munich in January 1914 to the Brand family. Auctioned in 1964 to Sol Kaplan, later sold to a Swiss collector.[26] | Unknown | |

| Schubert ruble without edge lettering |

Reichel-Schubert-Tolstoy ruble | 20.75 | The first Constantine ruble that became public through an 1857 publication by Schubert. In 1913 it was auctioned as part of count Tolstoy's estate.[27] In 1961 it was owned, along with several fakes, by A. E. Kelpsh, a Russian emigree to the United States. Kelpsh estate sold their Constantine ruble to a private customer in 1974 for US$200,000.[22][26] | Unknown |

| Josef-Richter ruble | 20.57 | This, according to Spassky, could be the coin secretly retained by Cancrin. It resurfaced in Saint Petersburg during World War I and was owned by Soviet collector Richter. Ivan Spassky examined the coin in 1962 and found that it matches the Hermitage press dies. After Richter's death the coin emerged in Germany. The new owner, numismatist Willhelm Fuchs, failed to sell it through Sotheby's in 1981; by 1990 it was believed to be in a private collection in the United States.[22][28] | Unknown | |

| Garshin-Fuchs ruble | 20.89 | Owned by Soviet collector Garshin (1887–1956). Twenty years after his death resurfaced in Germany in possession of Willhelm Fuchs. In 1979 it was offered for sale in the United States for US$114,000.[22][28] | Unknown |

The Trubetskoy fakes have become rare collectibles in their own right; two of these are preserved at the Hermitage and the Smithsonian (the latter is part of Georgy Mikhailovich collection).

Numerous other fakes, some of very high quality, circulated in Europe and Russia. They were pressed either from real, mass-produced silver coins of the period, or from soft alloys. According to Ivan Spassky, all high-quality fakes of this kind were pressed on the same set of dies.[15] According to Kalinin, the genuine press dies from the Hermitage are no longer good for minting. During World War II the Hermitage coin collection was evacuated from the city into deep rear. The dies were stored in inappropriately humid conditions that caused corrosion of the polished surfaces. Speckles of rust on the Hermitage dies, according to Kalinin, forever rule out their use (or abuse) for cloning the Constantine ruble.[29]

References

- By 1880 Russian numismatists were well aware of the existence of Constantine rubles, but their first printed description was published only in 1886 - Kalinin, p.1.

- Jonathan Schaffer (2009, November 29). Smithsonian Rare Russian Coin Collection Seeks Exhibition Sponsor Archived 2011-10-13 at the Wayback Machine. america.gov. Retrieved 02-03-2010.

- Kalinin, p. 1.

- Melnikova, p. 1.

- Spassky, p. 4.

- Spassky, pp. 5-6.

- Korf, p. 35.

- Korf, pp. 42-49.

- Korf, p. 65.

- Korf, p. 84.

- Korf, pp. 85-86.

- Korf, pp. 87-92.

- Bartoshevich, p. 1.

- Schukina 1991, pp. 1-4.

- Spassky, p. 3.

- Melnikova, p. 10.

- Bartoshevich, p. 2. .

- Melnikova, p. 2..

- Melnikova, p. 3.

- Melnikova, p. 5.

- Melnikova, p. 6. Exact dates of 1879-1880 events are provided in Spassky, pp. 3-6.

- Spassky 1991, p.2.

- Spassky, p. 2.

- Legendary Constantine Ruble Sets New Record in the New York Sale Auction as the World's Most Expensive Non-U.S. Coin. Russiancoins.net. Retrieved 03-03-2010.

- The Willis H. duPont - Georgii Mikhailovich Collection of Russian Coins and Medals Archived 2010-03-11 at the Wayback Machine. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 03-03-2020.

- Spassky, p. 5.

- Melnikova, p. 9.

- Spassky, p. 6

- Kalinin, p. 3.

Sources

- Korf, M. A. (1857). The accession of Nicholas I. London: John Murray.

- Melnikova, A. S. et al. (1991, in Russian). Konstantinovsky rubl. Novye materialy i opisaniya (Константиновский рубль. Новые материалы и исследования). Moscow: Finansy i statistika. ISBN 5-279-00490-1. Includes:

- Melnikova, A. S. (1991, in Russian). Konstantinovsky rubl i istoriya ego izuchenia (Константиновский рубль и история его изучения).

- Bartoshevich, V. V. (1991, in Russian). Zametki o konstantinovskob ruble (Заметки о константиновском рубле).

- Kalinin, V. A. (1991, in Russian). Iz istorii sozdaniya shtempeley konstantinovskogo rublya (Из истории создания штемпелей константиновского рубля).

- Schukina, E. S. (1991, in Russian). K voprosu o sozdatelyah shtempeley konstantinovskogo rublya (К вопросу о создателях штемпелей константиновского рубля).

- Spassky, I. G. (1991, in Russian). Novoye o ruble Konstantina 1825 g. i ego poddelkah (Новое о рубле Константина 1825 г. и его подделках).

External links

- Dies of the Rouble of Constantine Pavlovich. Hermitage Museum.