James Green (engineer)

James Green (1781–1849) was a noted civil engineer and canal engineer, who was particularly active in the South West of England, where he pioneered the building of tub boat canals, and inventive solutions for coping with hilly terrain, which included tub boat lifts and inclined planes. Although dismissed from two schemes within days of each other, as a result of construction problems, his contribution as a civil engineer was great.

James Green | |

|---|---|

| Born | 1781 Birmingham, England |

| Died | 1849 (aged 67–68) |

| Nationality | English |

| Occupation | Engineer |

| Engineering career | |

| Discipline | Civil and canal engineer |

| Projects | Bude Canal Rolle Canal Grand Western Canal Kidwelly and Llanelly Canal |

Early career

James Green was born in Birmingham, the son of an engineering family. He learned much from his father, by whom he was employed until the age of 20. He then worked with John Rennie on a number of projects around the country, until 1808, when he moved to Devon, and established a base at Exeter. He submitted plans for the rebuilding of Fenny Bridges, in East Devon, which had collapsed only 18 months after their previous reconstruction. The plans were accepted, and Green became the Bridge Surveyor for the County of Devon. By 1818 he had been promoted to Surveyor of Bridges and Buildings for the county, and held this position until 1841. These official duties did not prevent him from involvement in many private projects.[1]

His initial involvement with canals in the West Country included his appointment as engineer for the Braunton Canal and drainage scheme[2] and the Exeter and Crediton Canal. This project, which started in 1810, was abandoned in its early stages and was never completed. He was also involved with extending and enlarging the Exeter Ship Canal, a project which started in 1820 and lasted for seven years.[1]

Tub boats and inclined planes

James Green brought his own individual style to canal building. He was faced with the engineering problems of building canals in hilly terrain, where the water supply was limited. His solution was to advocate the use of tub boats, which were fairly small and capable of transporting between five and eight tons of goods, and rather than using conventional locks to alter the level of the canal, advocated the use of vertical lifts and inclined planes.[1]

The Bude Canal

The first project that used this approach was the Bude Canal, for which he presented a report in 1818, and then acted as engineer from 1819 to 1825. The plans included three conventional locks and six inclined planes. Five of the planes were powered by water wheels, which were located near the top of the planes. The sixth one, at Hobbacott, was 935 ft (285 m) long and raised the canal by 225 ft (69 m). It was powered by a system of buckets which descended and ascended in a pair of wells. Each bucket was capable of holding 15 tons of water, and they were attached to either end of a chain, which passed over a drum. The buckets were arranged so that when one was at the top of its well, the other was at the bottom. The top bucket was charged with water, and its weight then caused it to descend, raising the other bucket and a tub boat at the same time. When it reached the bottom, the water was automatically discharged, and ran along an adit to empty into the bottom level of the canal. The process was quick and efficient, raising a tub boat in about four minutes, which was half the time required when the standby 16 hp (12 kW) steam engine had to be used.[1]

Green took his inspiration for the methods of operating the planes from the work of Robert Fulton, but brought his own engineering skills to make a workable system.[1]

The Rolle Canal

Before working on the Bude Canal Green had been invited by Denys, Baron Rolle to draw up plans for a canal from Bideford to Torrington. He presented his report in 1810 but it was not until 1823 that construction commenced with Green as the engineer. As at Bude, the canal was designed for tub boat operation with a single, double track, inclined plane powered by a water wheel. The other notable feature was a five arch aqueduct carrying the canal across the River Torridge. The canal opened in 1827 with principal cargo being limestone and coal, both shipped from South Wales. These were processed in the limekilns built, also by Green, at the head of navigation in Great Torrington. The canal continued in use until 1871 when much of its course was converted to railway use. The sea-lock at Bideford can still be seen and the aqueduct now carries the drive to Beam House.

The Grand Western Canal

Green's next assignment was more ambitious. He was engineer for the Somerset section of the Grand Western Canal. The Devon section had been built as part of a proposed scheme to link the Bristol Channel to Exeter, but the scheme had foundered due to lack of finances, and the section near Tiverton was isolated, with the link to Taunton never having been built. In 1829, Green again proposed a tub-boat canal with inclined planes, but by 1830, this had been altered to seven vertical boat lifts and one inclined plane. Green acknowledged the ideas of Dr James Anderson of Edinburgh, who had proposed vertical boat lifts in 1796, but also noted that the proposals required interpretation to make them workable. Various prototypes had been built around the country, but none had proved successful.[1]

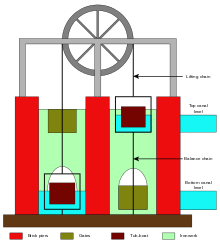

There were delays in the commissioning of the boat lifts, as Green struggled with the engineering problems. The lift consisted of two chambers, each holding a caisson, which was joined to the other by chains which passed over a series of wheels. Since a boat displaces its own weight of water, a caisson with a boat in it balances one with no boat in it. To make the system work, the top caisson was filled with about 2 inches (5.1 cm) of water more than the bottom one, and motion was provided by the extra weight of water, which was about a ton. The difficulties arose when the descending caisson reached the water in the bottom chamber. Anderson had suggested that the water level should be lower than the level of the canal, so that the caisson could sink low enough for the boat to float out. Green had not implemented this, and ultimately the problem was solved by constructing what amounted to a lock at the bottom, so that the boat floated out into the lock and descended the last 3 ft (0.91 m) as it would in a conventional lock.[1]

The inclined plane was more problematical. Green seems to have made an error in calculation, which resulted in the buckets being much too small. On the Bude Canal, he had used a 15-ton bucket to raise a five-ton boat. Here he had designed a 10-ton bucket, and the loaded boats weighed about 8 tons. Commissioning tests indicated that a bucket capable of holding 25 tons of water would be needed, but the shafts were not big enough. The novel power source had to be abandoned, to be replaced by a steam engine. Green was dismissed in January 1836.[1]

The Kidwelly and Llanelly Canal

Green was also involved in the extension of the Kidwelly and Llanelly Canal from 1833. Once again, he advocated a tub-boat canal, this time with three inclined planes: two twin-track inclines, which were counterbalanced, and a third, single-track incline, which required power. Ultimately, the power was supplied by a water wheel, but Green had to admit that he could not complete the inclines, as he had underestimated the cost of their construction by a huge margin. He was dismissed from the project on 30 January 1836, just three days after his dismissal from the Grand Western project.[3]

Final Days

The Grand Western and the Kidwelly and Llanelly Canal were the last canal projects that Green was involved in. He remained a prominent engineer, acting as a consultant for the Bristol Docks and the Newport Docks, and working on the South Devon Railway.[1] He remained responsible for hundreds of structures in Devon until he was 60, and died, aged 68, in 1849. At the time of his death his son Joseph D. Green was resident engineer at Bristol docks.[4]

Green had a prodigious workload for much of his career as an engineer, and it is not surprising that some mistakes were made.[3] Nevertheless, he made a huge contribution to civil engineering in South West England.

References

- Helen Harris (1996) The Grand Western Canal, Devon Books, ISBN 0-86114-901-7

- Clare Manning, (2007), Braunton Marsh Management Scheme, Taw Torridge Estuary Forum Archived 8 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- Raymond Bowen (2001) The Burry Port & Gwendreath Valley Railway and its Antecedent Canals, Oakwood Press, ISBN 0-85361-577-2

- Skempton, Alec (2002). A Biographical Dictionary of Civil Engineers in Great Britain and Ireland: 1500 to 1830. Thomas Telford. p. 270. ISBN 978-0-7277-2939-2.

- The Canals of South West England, David And Charles 1967