Rhodesian Security Forces

The Rhodesian Security Forces were the military forces of the Rhodesian government. The Rhodesian Security Forces consisted of a ground force (the Rhodesian Army), the Rhodesian Air Force, the British South Africa Police (BSAP), and various personnel affiliated to the Rhodesian Ministry of Internal Affairs (INTAF). Despite the impact of economic and diplomatic sanctions, Rhodesia was able to develop and maintain a potent and professional military capability.[1]

| Rhodesian Security Forces | |

|---|---|

.png) Emblem of the Rhodesian Army. Following the declaration of a republic in 1970, St Edward's Crown was removed. | |

| Founded | 1964 |

| Disbanded | 1980 |

| Service branches | |

| Headquarters | Salisbury, Rhodesia |

| Leadership | |

| Commander-in-Chief | See list |

| Minister of Defence | See list |

| Head of the Rhodesian Armed Forces | See list |

| Related articles | |

| History | Rhodesian Bush War |

| Ranks | Military ranks |

The Rhodesian Security Forces of 1964–80 traced their history back to the British South Africa Company armed forces, originally created during company rule in the 1890s. These became the armed forces of the British self-governing colony of Southern Rhodesia on its formation in 1923, then part of the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland military in 1953. After the break-up of the Federation at the end of 1963, the security forces assumed the form they would keep until 1980.

As the armed forces of Rhodesia (as Southern Rhodesia called itself from 1964), the Rhodesian Security Forces remained loyal to the Salisbury government after it unilaterally declared independence from Britain on 11 November 1965. Britain and the United Nations refused to recognise this, and regarded the breakaway state as a rebellious British colony throughout its existence.

The security forces fought on behalf of the unrecognised government against the Zimbabwe African National Liberation Army (ZANLA) and the Zimbabwe People's Revolutionary Army (ZIPRA)—the military wings of the Marxist–Leninist black nationalist Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU) and Zimbabwe African People's Union (ZAPU) respectively—during the Rhodesian Bush War of the 1960s and 1970s.

The Lancaster House Agreement and the return of Rhodesia to de facto British control on 12 December 1979 changed the security forces' role altogether; during the five-month interim period, they helped the British governor and Commonwealth Monitoring Force to keep order in Rhodesia while the 1980 general election was organised and held. After the internationally recognised independence of Zimbabwe in April 1980, the Rhodesian security forces, ZANLA and ZIPRA were integrated to form the new Zimbabwe Defence Forces.

Rhodesian Army

| Rhodesian Army | |

|---|---|

Flag of the Rhodesian Army, used during the late 1970s. | |

| Active | 1927–1980 |

| Disbanded | 18 April 1980 |

| Country | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch | Ground Forces |

| Garrison/HQ | Salisbury, Rhodesia |

| Colors | Rifle Green |

| Equipment | FN FAL Rhodesian Brushstroke |

| Engagements | First World War

Second World War Rhodesian Bush War |

| Commanders | |

| Last Commander | Lt Gen George Peter Walls |

| Insignia | |

| Shoulder flash & recruitment logo | .png) |

The majority of the Southern Rhodesia Volunteers were disbanded in 1920 for reasons of cost, the last companies being disbanded in 1926. The Defence Act of 1927 created a Permanent Force (the Rhodesian Staff Corps) and a Territorial Force as well as national compulsory military training.[2] With the Southern Rhodesia Volunteers disbanded in 1927, the Rhodesia Regiment was reformed in the same year as part of the nation's Territorial Force. The 1st Battalion was formed in Salisbury with a detached "B" company in Umtali and the 2nd Battalion in Bulawayo with a detached "B" Company in Gwelo.[3] Between the World Wars, the Permanent Staff Corps of the Rhodesian Army consisted of only 47 men. The British South Africa Police (BSAP) were trained as both policemen and soldiers until 1954.[4]

About 10,000 white Southern Rhodesians (15% of the white population) mustered into the British forces during the Second World War, serving in units such as the Long Range Desert Group, No. 237 Squadron RAF and the Special Air Service (SAS). Pro rata to population, this was the largest contribution of manpower by any territory in the British Empire, even outstripping that of Britain itself.[5]

Southern Rhodesia's own units, most prominently the Rhodesian African Rifles (made up of black rank-and-filers and warrant officers, led by white officers; abbreviated RAR), fought in the war's East African Campaign and in Burma.[6] During the war, Southern Rhodesian pilots proportionally earned the highest number of decorations and ace appellations in the Empire. This resulted in the Royal Family paying an unusual state visit to the colony at the end of the war in thanks to the efforts of the Rhodesian people.

The Southern Rhodesia Air Force (SRAF) was re-established in 1947 and, two years later, Prime Minister Sir Godfrey Huggins appointed a 32-year-old South African-born Rhodesian Spitfire pilot, Ted Jacklin, as air officer commanding tasked to build an air force in the expectation that British African territories would begin moving towards independence, and air power would be vital for land-locked Southern Rhodesia. The threadbare SRAF bought, borrowed or salvaged a collection of vintage aircraft, including six Tiger Moths, six North American Harvard trainers, an Avro Anson freighter and a handful of De Havilland Rapide transport aircraft, before purchasing a squadron of 22 Mk. 22 war surplus Supermarine Spitfire from the Royal Air Force (RAF) which were then flown to Southern Rhodesia.[7]

In April 1951, the defence forces of Southern Rhodesia were completely reorganised.[8] The Permanent Force included the BSAP as well as the Southern Rhodesia Staff Corps, charged with training and administering the Territorial Force. The SRAF consisted of a communication squadron and trained members of the Territorial Force as pilots, particularly for artillery observation. During the Malayan Emergency of the 1950s, Southern Rhodesia contributed two units to the Commonwealth's counter-insurgency campaign: the newly formed Rhodesian SAS served a two-year tour of duty in Malaya starting in March 1951,[9] then the Rhodesian African Rifles operated for two years from April 1956.[10]

The colony also maintained women's auxiliary services (later to provide the inspiration for the Rhodesia Women's Service), and maintained a battalion of the RAR, officered by members of the Staff Corps. The Territorial Force remained entirely white and largely reproduced the Second World War pattern. It consisted of two battalions of the Royal Rhodesia Regiment, an Armoured Car Regiment, Artillery, Engineers, Signal Corps, Medical Corps, Auxiliary Air Force and Transport Corps. In wartime the country could also draw on the Territorial Force Reserve and General Reserve. Southern Rhodesia, in other words, reverted more or less to the organisation of the Second World War.

Matters evolved greatly over twenty years. The regular army was always a relatively small force, but by 1978–79 it consisted of 10,800 regulars nominally supported by about 40,000 reservists. While the regular army consisted of a professional core drawn from the white population (and some units, such as the Rhodesian SAS and the Rhodesian Light Infantry, were all-white), by 1978–79 the majority of its complement was actually composed of black soldiers. The army reserves, in contrast, were largely white.[11]

The Rhodesian Army HQ was in Salisbury and commanded over four infantry brigades and later an HQ Special Forces, with various training schools and supporting units. Numbers 1,2, and 3 Brigade were established in 1964 and 4 Brigade in 1978.[12]

- 1 Bde – Bulawayo with area of responsibility in Matabeleland

- 2 Bde – Salisbury with area of responsibility in Mashonaland

- 3 Bde – Umtali with area of responsibility in Manicaland

- 4 Bde – Fort Victoria with area of responsibility in Victoria province

During the Bush War, the army included:

- Army Headquarters

- The Rhodesian Light Infantry

- C Squadron (Rhodesian) SAS (in 1978 became 1 (Rhodesian) Special Air Service Regiment)

- Selous Scouts

- The Rhodesian Armoured Car Regiment (The Black Devils)

- Grey's Scouts

Eland-90 armoured cars of the Rhodesian Armoured Corps.

Eland-90 armoured cars of the Rhodesian Armoured Corps. - The Rhodesian African Rifles (also including independent companies numbered 1–6 and, briefly, 7)

- The Rhodesia Regiment (eight battalions, numbered 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 8, 9, 10)

- 1 Psychological Operations Unit

- The Rhodesian Defence Regiment (two battalions)

- The Rhodesian Intelligence Corps

- The Rhodesian Artillery (one depot, one field regiment)

- Six Engineer Squadrons (numbered 2, 3, 4, 6, 7) 1 Engr Sqn

- 5 Engineer Support Squadron

- 1 Brigade [13]

- Headquarters Abbreviation: HQ 1 Bde

- Signals Squadron Abbreviation: 1(Bde) Sig Sqn

- 2 Brigade [13]

- Headquarters Abbreviation: HQ 2 Bde

- Signals Squadron Abbreviation: 2(Bde) Sig Sqn

- 12 Signals Squadron Abbreviation: 2(Bde) 12 Sig Sqn[14]

- Located: Llewellyn Barracks

- 12 Signals Squadron Abbreviation: 2(Bde) 12 Sig Sqn[14]

- 3 Brigade [13]

- Headquarters Abbreviation: HQ 3 Bde

- Signals Squadron Abbreviation: 3(Bde) Sig Sqn

- 4 Brigade [13]

- Headquarters Abbreviation: HQ 4 Bde

- 41 Troop, Signals Squadron Abbreviation: 41 Tp 4(Bde) SigSqn

- Two Services Area HQs (Matabeleland and Mashonaland)

- Two Ordnance and Supplies Depots (Bulawayo, Salisbury)

- Two Base Workshops (Bulawayo, Salisbury)

- 1 Air Supply Platoon

- Three Maintenance Companies (numbered 1 to 3)

- Three Medical Companies (1, 2, 5) and the Army Health Unit

- Tsanga Lodge

- Five Provost Platoons (numbered 1 to 5) and the Army Detention Barracks

- Six Pay Companies (numbered 1 to 5, 7)

- Rhodesian Army Education Corps

- Rhodesian Corps of Chaplains

- Army Records, and Army Data Processing Unit

- Rail Transport Organisation Platoon

- 1 Military Postal Platoon

- Training establishments: School of Infantry, 19 Corps Training Depot, School of Military Engineering, School of Signals, Services Training School, Services Trade Training Centre, Medical Training School, School of Military Police, Pay Corps Training School, School of Military Administration.

Ranks

| Equivalent NATO Code | OF-10 | OF-9 | OF-8 | OF-7 | OF-6 | OF-5 | OF-4 | OF-3 | OF-2 | OF-1 | OF(D) & Student officer | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

(Edit) |

No equivalent |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Unknown | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| General | Lieutenant general | Major general | Brigadier | Colonel | Lieutenant Colonel | Major | Captain | Lieutenant | Second Lieutenant | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Equivalent NATO code | OR-9 | OR-8 | OR-7 | OR-6 | OR-5 | OR-4 | OR-3 | OR-2 | OR-1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

(Edit) |

|

|

|

|

No equivalent | No insignia | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Warrant Officer Class 1 | Warrant Officer Class 2 | Staff Sergeant | Sergeant | Corporal | Lance Corporal | Private (or equivalent) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Rhodesian Air Force

The Royal Rhodesian Air Force (RRAF), as it was named in 1954, was never a large air force. In 1965, it consisted of only 1,200 regular personnel. It was renamed as the Rhodesian Air Force (RhAF) in 1970. At the peak of its strength during the Bush War, it had a maximum of 2,300 personnel of all races, but of these, only 150 were pilots actively involved in combat operations. These pilots, however, were rotated through the various squadrons partly to maintain their skills on all aircraft and partly to relieve fellow pilots flying more dangerous sorties.

| Equivalent NATO Code | OF-10 | OF-9 | OF-8 | OF-7 | OF-6 | OF-5 | OF-4 | OF-3 | OF-2 | OF-1 | OF(D) and student officer | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

(Edit) |

No equivalent |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Air Marshal | Air Vice-Marshal | Air Commodore | Group Captain | Wing Commander | Squadron Leader | Flight Lieutenant | Air Lieutenant | Air Sub-Lieutenant | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Equivalent NATO Code | OR-9 | OR-8 | OR-7 | OR-6 | OR-5 | OR-4 | OR-3 | OR-2 | OR-1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

(Edit) |

|

|

|

|

|

No equivalent |  |

No equivalent |  |

|

No insignia | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Station Warrant Officer | Warrant Officer Class 1 | Flight sergeant | Sergeant | Corporal | Senior Aircraftsman | Leading Aircraftman | Aircraftman | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

British South Africa Police (BSAP)

The British South Africa Police (BSAP) were the first line of defence in both Southern Rhodesia and, later, Rhodesia, with the specific responsibility of maintaining law and order in the country.[12]

INTAF

While not a part of the Security Forces, Rhodesian Ministry of Internal Affairs (INTAF) officers were heavily involved in implementing such civic measures as the protected villages programme during the Bush War.

Prison Services

The Rhodesia Prison Service (RPS) was the branch of the Rhodesian Security Forces responsible for the administration of Rhodesian prisons.

Guard Force

This was the fourth arm of the Rhodesian Security Forces. It consisted of both black and white troops whose initial role was to provide protection for villagers in the Protected Village system. During the latter stages of the Bush War they provided a role in the protection of white-owned farmland, tribal purchase lands and other strategic locations. They also raised two infantry Battalions and provided troops in every facet of the war in each of the Operational Areas. It was a large component of the Security Forces, with a strength of over 7,200 personnel. Its headquarters were in North Avenue, Salisbury. Its training establishment was based at Chikurubi in Salisbury.

The guard force cap badge was a castle on top of a dagger, below the castle was a scroll reading 'Guard Force'

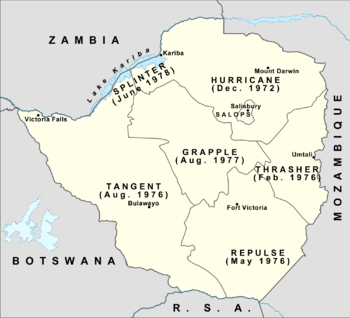

Combined Operations

The Rhodesian Bush War required that each of the security forces work in a combined effort to combat the enemy. Therefore it became essential to establish an organisation known as Combined Operations (COMOPS) in Salisbury to co-ordinate the efforts of each service. The Rhodesian army took the senior role in Combined Operations and was responsible for the conduct of all operations both inside and outside Rhodesia. COMOPS had direct command over the Joint Operational Centres (JOCs) deployed throughout the country in each of the Operational Areas. There was a JOC per Operational Area.[12]

The operational areas were known as:

- Operation Hurricane – North-east border, started in December 1972

- Operation Thrasher – Eastern border, started in February 1976

- Operation Repulse – South-east border, started in May 1976

- Operation Tangent – Matabeleland, started in August 1976

- Operation Grapple – Midlands, started in August 1977

- Operation Splinter – Kariba, started in June 1978

- Salops – Operations in and around Salisbury, started in 1978

Senior military officials in Rhodesia

Source: original regiments.org (T.F. Mills) via webarchive.

- Commandant, Southern Rhodesia Defence Force:

- Chief of the General Staff:

- 1953 Maj-Gen. Storr "Dooley" Garlake, CBE[18]

- 1959.04.12 Maj-Gen. Robert Edward Beaumont Long, CBE

- 1963.06 Maj-Gen. John Anderson, CBE

- 1964.10.24 Maj-Gen. Rodney Roy Jensen Putterill, CBE[19]

- 1968.10 Maj-Gen. Keith Robert Coster, OBE

- Commander of the Rhodesian Army:

- 1977.05.16 Lt-Gen. John Selwyn Varcoe Hickman, CLM, MC

- 1979.03.06 Lt-Gen. George Peter Walls GLM DCD MBE

- Commander Zimbabwe Defence Forces:

- 1981.08 Gen. Andrew Lockhart Charles Maclean

Military equipment of Rhodesia

Small arms

| Name | Type | Country of origin | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Browning Hi-Power[20] | Semi-Automatic Pistol | ||

| Enfield revolver | Revolver | Enfield No. 2 Mk I Revolver. | |

| Mamba | Semi-Automatic Pistol | ||

| Star[21] | Semi-Automatic Pistol | Model 1920, 1921, 1922. | |

| Walther PP[21] | Semi-Automatic Pistol | Captured. | |

| Austen[22] | Submachine gun | Austen "Machine Carbine" Mk I. | |

| Sanna 77 | Submachine gun | Issued primarily to INTAF. | |

| Northwood R-76 | Submachine gun | ||

| Owen Gun[22] | Submachine gun | ||

| Sa 25 (vz. 48b) | Submachine gun | Some of local manufacture. | |

| Sten[22] | Submachine gun | Mk II. | |

| Sterling[20] | Submachine gun | ||

| Uzi[23] | Submachine gun | Some of local manufacture. | |

| AK-47[24] | Assault Rifle | Captured. | |

| AKM[25] | Assault Rifle | Captured and used by RhACR. | |

| FN FAL[21] | Battle Rifle | Belgian FNs, South African R1s. | |

| Heckler & Koch G3[21] | Battle Rifle | G3A3, received from Portugal. | |

| L1A1[21] | Battle Rifle | Issued primarily to reservists. | |

| Lee–Enfield[26] | Bolt-action rifle | Some converted into sniper rifles. | |

| M16A1[20] | Assault rifle | Used very late in the war. | |

| Mini-14 | Semi-Automatic rifle | Smuggled from U.S. | |

| SKS | Semi-automatic rifle | Captured. | |

| Bren | Light machine gun | Mk 3. | |

| Browning M2 | Heavy machine gun | ||

| Browning M1919[21] | Medium machine gun | Helicopter-mounted weapon. | |

| Degtyaryov 1938/46[27] | Light machine gun | Captured. | |

| FN MAG[21] | General purpose machine gun | MAG-58. | |

| KPV | Heavy machine gun | Captured. | |

| PKM | General purpose machine gun | Captured. | |

| RPD[21] | Light machine gun | Captured. | |

| RPK | Light machine gun | Captured. | |

| Browning Auto-5[21] | Shotgun | ||

| Ithaca 37 | Shotgun | ||

| Dragunov | Sniper rifle | Captured. | |

| Armscor M963 | Fragmentation grenade | Sourced via South Africa, Derived from INDEP's licence-made M26 grenade | |

| STRIM 32Z[28][29][30] | Anti-tank rifle grenade | Sourced via South Africa? | |

| STRIM 28R[29][31][32] | Rifle grenade | Sourced via South Africa? | |

| PRB 424 | Rifle grenade | ||

| Armscor 42 Zulu | Rifle grenade | Sourced via South Africa, Derived from PRB 424 | |

| Mecar ENERGA | Anti-tank Rifle grenade | Latterly sourced via South Africa | |

| M18 Claymore[20] | Anti-personnel mine | ||

| Mine G.S. Mk V | Anti-tank mine | ||

| Bazooka | Anti-tank weapon | M20 Super Bazooka. | |

| M72 LAW | Anti-tank weapon | ||

| RPG-2[33] | Anti-tank weapon | Captured. | |

| RPG-7[20] | Anti-tank weapon | Captured. |

Missiles and Recoilless Rifles

| Name | Type | Country of Origin | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| MILAN | Anti-tank missile | 9 launchers, 75 missiles. | |

| M40 | Anti-tank weapon | ||

| B-11 | Anti-tank weapon | Captured late in the war.[34] |

Vehicles

| Name | Type | Country of Origin | In Service | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scout & reconnaissance cars | ||||

| BRDM-2 | Scout Car | Captured. | ||

| Eland[23] | Reconnaissance car | 34 | ||

| Ferret[35] | Scout Car | 10 | Mk 2/2. | |

| Marmon-Herrington[35] | Reconnaissance car | |||

| T17E1 Staghound[35] | Reconnaissance car | 20 | ||

| Utility trucks | ||||

| Mercedes-Benz L1517[35] | Utility Truck | |||

| Mercedes-Benz LA911B[35] | Utility Truck | |||

| Mercedes-Benz LA1113/42[35] | Utility Truck | |||

| Bedford MK[35] | Utility truck | |||

| Bedford RL[35] | Utility truck | |||

| Unimog 416[21] | Utility Truck | |||

| Armoured personnel carriers | ||||

| Buffel | Wheeled Personnel Carrier | |||

| Bullet[35] | Infantry Fighting Vehicle | 1 | ||

| Crocodile[35] | Wheeled Personnel Carrier | 130 | ||

| MAP75[35] | Wheeled Personnel Carrier | 200-300 | ||

| MAP45[35] | Wheeled Personnel Carrier | 100-200 | ||

| Leopard[35] | MPAV | |||

| Mine Protected Combat Vehicle[35] | Infantry Fighting Vehicle | 60 | ||

| Pookie | Mine Detection and Removal (by Contact) vehicle | Built on Volkswagen Kombi chassis.[35] | ||

| Hippo[23] | Wheeled Personnel Carrier | |||

| Shorland[35] | Armoured Car | 2 | Custom hulls and Ferret turrets. | |

| Thyssen Henschel UR-416[36] | Armoured Personnel Carrier | 2 | ||

| Universal Carrier[35] | Armoured Personnel Carrier | 30 | Improved Universal Bren carrier. | |

| Tanks | ||||

| T-34[37] | Medium Tank | 5–10 | Captured from Mozambique. | |

| T-55[35] | Main Battle Tank | 8 | Polish T-55LD tanks provided by South Africa. | |

| 4×4 light vehicles | ||||

| Mazda B1600[35] | Light truck | 300 | Fitted with machine gun turret. | |

| Land Rover | 4×4 Vehicle | Mine-resistant variant designated Armadillo.[35] | ||

| Willys MB | Jeep | M38. | ||

Artillery

| Name | Type | Country of Origin | In Service | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BL 5.5[23] | 140mm Howitzer | 4 | ||

| BM-21 Grad | 122mm Multiple Rocket Launcher | Captured. | ||

| L16[23] | 81mm Mortar | 30 | ||

| M101[38] | 105mm Howitzer | 6 | ||

| Ordnance QF 25 pounder[23] | 87mm Howitzer | 18 | ||

| OTO Melara Mod 56 | 105mm Howitzer | 18 |

Air Defence

| Name | Type | Country of Origin | In Service | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 37mm Gun M1 | Anti-aircraft gun | |||

| Oerlikon 20 mm cannon[27] | Anti-aircraft gun | 1 | Captured. | |

| Zastava M55 20mm autocannon[39] | Anti-aircraft gun | Captured. | ||

| Strela 2 | Surface-To-Air Missile System | 15 | Captured. | |

| ZPU[38] | Anti-aircraft gun | 10 | Captured. | |

| ZU-23-2 | Anti-aircraft gun | Captured. |

Air force equipment

| Name | Type | Country of Origin | In Service | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aermacchi AL-60[23] | Utility Aircraft | 9 | AL-60F-5 "Trojan". | |

| Aermacchi SF.260[23] | Trainer Aircraft/Light Attack Aircraft | 17 | SF.260C and SF.260W "Genet". | |

| SNIAS Alouette-II[23] | Light Transport Helicopter | 10 | ||

| Aérospatiale Alouette III[23] | Helicopter | 27 | Several supplied by the SAAF. | |

| Beechcraft Baron[40] | Transport Aircraft | 1 | Baron 95 C-55. | |

| Bell UH-1 Iroquois[23] | Helicopter | 10 | Agusta-Bell 205A. Used very late in the war. | |

| Britten-Norman Islander[23] | Transport Aircraft | 6 | ||

| Canadair North Star | Transport Aircraft | 4 | C-4 Argonaut. | |

| Cessna 185 | Utility Aircraft | 17 | ||

| Cessna 421 | Transport Aircraft | 1 | ||

| Cessna Skymaster[23] | Light Attack Aircraft | 10 | Reims-Cessna FTB 337G 'Lynx'. | |

| de Havilland Vampire[40] | Fighter | 12 | ||

| Douglas C-47 Dakota[23] | Transport Aircraft | 12 | ||

| Douglas DC-7 | Transport Aircraft | 2 | ||

| English Electric Canberra[23] | Bomber | 7 | ||

| Hawker Hunter[23] | Fighter | 13 | Hunter FGA 9. | |

| North American T-6 Texan | Trainer Aircraft | 21 | AT-6 Harvard, sold to South Africa. | |

| Percival Pembroke | Transport Aircraft | 2 | Percival Pembroke C.1 | |

| Percival Provost[40] | Trainer Aircraft | 8 | Provost Mk 52. | |

| Supermarine Spitfire | Fighter | 22 | Mk 22. | |

| Golf[41] | General-purpose bomb | |||

| Alpha | Cluster bombs | The Canberra carried 300 Alpha bombs in groups of 50 inside six hoppers fitted to the bomb bay[42] | ||

| SNEB 68mm | Aircraft rockets |

See also

Notes and references

- References

- Rogers 1998, p. 41

- Wilson, Graham Cap badges of the Rhodesian Security Forces Sabretache, June 2000

- p.46 Radford

- Archived 18 July 2002 at the Wayback Machine

- Gale 1973, pp. 88–89; Young 1969, p. 11

- Binda 2007, pp. 41–42, 59–77

- Moss (n.d.); Petter-Bowyer (2003) p. 16

- Extracted from 'The Development of Southern Rhodesia's Military System, 1890–1953 by L. H. Gann, M.A., B.LITT., D.PHIL.'

- Binda 2007, p. 127; Shortt & McBride 1981, pp. 19–20

- Binda 2007, pp. 127–128

- Lohman & MacPherson 1983, chpt. 3

- Combined Operations – Brothers in Arms Archived 22 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- "Rhodesian Army Order of Seniority as at 26th February 1979". rhodesianforces.org. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- unconfirmed

- Abbott & Botham 1986, p. 7

- Cilliers 1984, p. 29

- Salt, Beryl (2000). A Pride of Eagles: A History of the Rhodesian Air Force. Covos Day Books. p. 301. ISBN 0-620-23759-7. Retrieved 7 August 2018.

- Waters, Jonathan (31 December 2011). "Obituary: Peter Garlake 1934-2011". Zimbabwefood. Retrieved 7 August 2018.

- Grundy, Trevor (5 December 2007). "Sam Putterill". The Herald Scotland. Retrieved 7 August 2018.

- Moorcraft, Paul L.; McLaughlin, Peter (April 2008) [1982]. The Rhodesian War: A Military History. Barnsley: Pen and Sword Books. ISBN 978-1-84415-694-8.

- Chris Cocks. Fireforce: One Man's War in the Rhodesian Light Infantry (1 July 2001 ed.). Covos Day. pp. 31–141. ISBN 1-919874-32-1.

- Small Arms (Museum exhibit), Saxonwold, Johannesburg: South African National Museum of Military History, 2012

- Nelson, Harold. Zimbabwe: A Country Study. pp. 237–317.

- Rod Wells. Part-Time War (2011 ed.). Fern House. p. 155. ISBN 978-1-902702-25-4.

- http://www.rhodesia.nl/quartz.htm

- http://usacac.army.mil/cac2/cgsc/carl/download/csipubs/ArtOfWar_RhodesianAfricanRifles.pdf

- http://img205.imageshack.us/img205/1605/32591727ik7.jpg

- Croukamp, Dennis (2007). "Chapter 10 Border Control & More Operations". Bush War in Rhodesia. Boulder, Colorado: Paladin Press. ISBN 978-1-58160-992-9.

Rifle Grenade Used as a Hammer: 'While I had been away on leave [in 1969], a new piece of ordnance had arrived. This was a 32Z anti-tank rifle grenade that fitted over the end of a rifle barrel and was propelled by a ballistic cartridge. As everyone else had fired a practice 32Z grenade, I thought it would be a really good idea for me to fire one.'

- Baxter, Peter; Bomford, Hugh; van Tonder, Gerry, eds. (2014). Rhodesia Regiment 1899-1981. Johannesburg: 30 Degrees South Publishers. pp. 471–488. ISBN 978-1-92014-389-3.

The Rhodesian rifle grenade manual (for the 32Z and 28R) was the source

- "Military Surplus Virtual Museum - French 40mm STRIM AP Type 32ZA Rifle Grenade". www.buymilsurp.com. 1 March 2009. Retrieved 4 May 2016.

- Walsh, Toc (2014). Mampara: Rhodesia Regiment Moments of Mayhem by a Moronic, Maybe Militant, Madman. Johannesburg: 30 Degrees South Publishers. pp. 74, 140. ISBN 978-1-92821-130-3.

There is a photo on page 120 of a Rhodesian 28R rifle grenade attached to a rifle

- "Armas utilizadas en la guerra de Rhodesia 1964-1979" [Weapons used in the war of Rhodesia 1964-1979] (in Spanish). 5 September 2012. Retrieved 4 May 2016.

- Anthony Trethowan. Delta Scout: Ground Coverage operator (2008 ed.). 30deg South Publishers. p. 185. ISBN 978-1-920143-21-3.

- Gerry van Tonder (1 May 2012). "Operation Aztec: 28 May 1977" (PDF). www.rhodesianservices.org. Retrieved 11 May 2016.

Weaponry included 81mm mortars and a Russian B19[sic] recoilless rifle.

- Peter Locke, David Cooke. Fighting Vehicles and Weapons of Rhodesia 1965–80. pp. 5–152.

- "WAR SINCE 1945 SEMINAR AND SYMPOSIUM, Chapter 3". Ohio State University. n.d. Retrieved 12 October 2013.

- "Rhodesian Armoured Car Regiment Uncovered". rhodesianforces.org. Retrieved 18 June 2013.

- John Keegan, page 589 World Armies, ISBN 0-333-17236-1

- Photos of a Zastava M55 autocannon captured by the Rhodesian Security Forces in Mozambique, September 1979.

- Rhodesia. Deadline Data on World Affairs, 1979 Volume, Issue October 1 p. 1-5.

- "RhAF The Armament Story · 1951 - 1980". www.ourstory.com/orafs. Retrieved 11 May 2016.

- "Air Force Weapons: Alpha Bomb". Dean Wingrin. Retrieved 11 May 2016.

- Journal articles

- Lohman, Major Charles M.; MacPherson, Major Robert I. (7 June 1983). "Rhodesia: Tactical Victory, Strategic Defeat" (PDF). War since 1945 Seminar and Symposium. Quantico, Virginia: Marine Corps Command and Staff College. Retrieved 19 October 2011.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bibliography

- Abbott, Peter; Botham, Philip (June 1986). Modern African Wars: Rhodesia, 1965–80. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-0-85045-728-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Binda, Alexandre (November 2007). Heppenstall, David (ed.). Masodja: The History of the Rhodesian African Rifles and its forerunner the Rhodesian Native Regiment. Johannesburg: 30° South Publishers. ISBN 978-1920143039.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cilliers, Jakkie (December 1984). Counter-Insurgency in Rhodesia. London, Sydney & Dover, New Hampshire: Croom Helm. ISBN 978-0-7099-3412-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gale, William Daniel (1973). The years between 1923–1973: half a century of responsible government in Rhodesia. Salisbury: H. C. P. Andersen.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Locke, Peter G; Cooke, Peter D F (1995). Fighting Vehicles and Weapons of Rhodesia 1965-80. Wellington: P & P Publishing. ISBN 978-0-47302-413-0. OCLC 40535718.

- Rogers, Anthony (1998). Someone Else's War: Mercenaries from 1960 to the Present. Hammersmith: Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0-00-472077-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Shortt, James; McBride, Angus (1981). The Special Air Service. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 0-85045-396-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Young, Kenneth (1969). Rhodesia and Independence: a study in British colonial policy. London: J. M. Dent & Sons.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Cross, Glenn (2017). Dirty War: Rhodesia and Chemical Biological Warfare, 1975–1980. Solihull, UK: Helion & Company. ISBN 978-1-911512-12-7.

External links

- Rhodesian Militaria: Army – Detailed photos & descriptions of genuine Army & Brigade patches.

- http://rhodesianforces.org

- http://www.rhodesia.nl

- http://www.baragwanath.co.za/leopard – Rhodesian 'Leopard' Mine Protected Vehicle on display at the War Museum, Johannesburg.