Río Cachirí Group

The Río Cachirí Group (Spanish: Grupo Río Cachirí, PZc) is a geological group of the Cesar-Ranchería Basin, Colombia and the Serranía del Perijá of the northernmost Colombian and Venezuelan Andes. The group of shales, sandstones and limestones is of Devonian age and has a maximum thickness in the Venezuelan section of 2,438 metres (7,999 ft). The group contains abundant fauna; crinoids, bryozoa, brachiopods and molluscs have been found in the group.

| Río Cachirí Group Stratigraphic range: Devonian 419–360 Ma | |

|---|---|

| Type | Geological group |

| Unit of | Cesar-Ranchería Basin, Serranía del Perijá |

| Sub-units | Caño Grande Fm., Caño del Oeste Fm., Campo Chico Fm., Los Guineos Fm. |

| Underlies | Carboniferous sequence |

| Overlies | Perijá Formation |

| Thickness | ~1,100 m (3,600 ft) (Colombia) 2,438 m (7,999 ft) (Venezuela) |

| Lithology | |

| Primary | Shale, sandstone |

| Other | Limestone |

| Location | |

| Coordinates | 10°50′03″N 72°14′23″W |

| Region | Cesar, La Guajira Zulia |

| Country | |

| Extent | ~110 km (68 mi) (Venezuela) |

| Type section | |

| Named for | Río Cachirí |

| Named by | Liddle |

| Location | Mara |

| Year defined | 1928 |

| Coordinates | 10°50′03″N 72°14′23″W |

| Region | Zulia |

| Country | |

| Thickness at type section | 2,438 m (7,999 ft) |

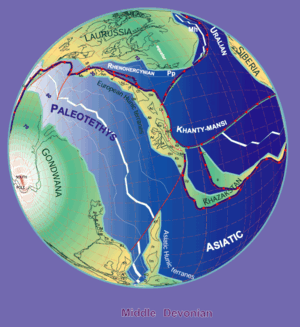

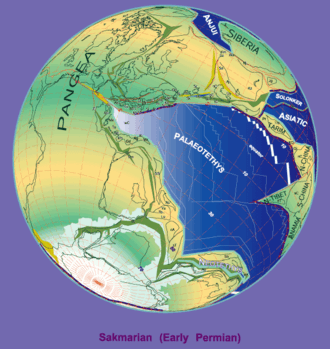

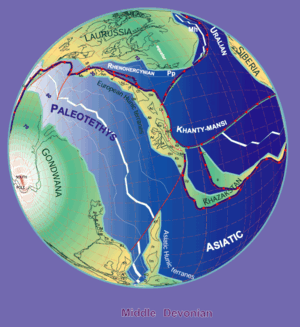

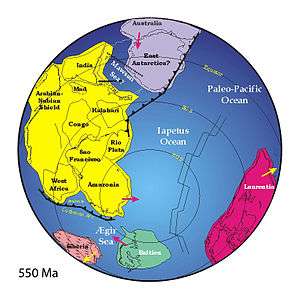

Paleogeography of the Middle Devonian 380 Ma, by Stampfli & Borel | |

Etymology and definition

The formation was defined by Liddle in 1928 in Río Cachirí, part of Mara, Zulia, in the Venezuelan part of the Serranía del Perijá, and the same author subdivided the group into three formations in 1943. In 1972, Bowen added a fourth formation to the group.[1]

Description

Lithologies

The group contains black, grey and red shales, grey micaceous sandstones, quartzitic sandstones and red and bluish grey limestones.[1]

Stratigraphy and correlation

The Río Cachirí Group, dated to span the Devonian, is subdivided into the Caño Grande, Caño del Oeste, Campo Chico and Los Guineos Formations. The maximum thickness has been recorded in Venezuela, with 2,438 metres (7,999 ft), while the thickness on the Colombian side of the range does not exceed 1,100 metres (3,600 ft).[1] The group is recognised along a section of approximately 110 kilometres (68 mi) in the Venezuelan terrain.[2] The group unconformably overlies the Perijá Formation and is overlain by an unnamed Carboniferous sequence. The Río Cachirí Group is time-equivalent with the Floresta and Cuche Formations of the Floresta Massif, Altiplano Cundiboyacense and the Quetame Group of the Eastern Ranges.[3] The sediments of the Río Cachirí Group were deposited in an epicontinental sea at the edge of the Paleo-Tethys Ocean.[1]

Fossil content

The group contains abundant fossils of crinoids, bryozoa, brachiopods and molluscs as Acrospirifer olssoni, Spirifer kingi, Leptaena boyaca, Fenestella venezuelansis, Neospirifer latus, Composita subtilita, Phricodrotis planoconvexa and Pecten sp.[4]

Outcrops

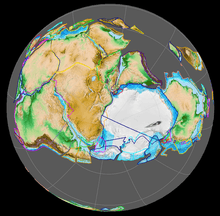

.jpg)

Apart from its type locality on the eastern flank of the Serranía del Perijá in Zulia, Venezuela, the formation is also found in other parts of the mountain range, on the Colombian western side in the east of San Diego and Curumaní, Cesar.[5][6]

Regional correlations

| Ma | Age | Paleomap | Regional events | Catatumbo | Cordillera | proximal Llanos | distal Llanos | Putumayo | VSM | Environments | Maximum thickness | Petroleum geology | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.01 | Holocene |  | Holocene volcanism Seismic activity | alluvium | Overburden | ||||||||

| 1 | Pleistocene |  | Pleistocene volcanism Andean orogeny 3 Glaciations | Guayabo | Soatá Sabana | Necesidad | Guayabo | Gigante Neiva | Alluvial to fluvial (Guayabo) | 550 m (1,800 ft) (Guayabo) | [7][8][9][10] | ||

| 2.6 | Pliocene |  | Pliocene volcanism Andean orogeny 3 GABI | Subachoque | |||||||||

| 5.3 | Messinian | Andean orogeny 3 Foreland | Marichuela | Caimán | Honda | [9][11] | |||||||

| 13.5 | Langhian | Regional flooding | León | hiatus | Caja | León | Lacustrine (León) | 400 m (1,300 ft) (León) | Seal | [10][12] | |||

| 16.2 | Burdigalian | Miocene inundations Andean orogeny 2 | C1 | Carbonera C1 | Ospina | Proximal fluvio-deltaic (C1) | 850 m (2,790 ft) (Carbonera) | Reservoir | [11][10] | ||||

| 17.3 | C2 | Carbonera C2 | Distal lacustrine-deltaic (C2) | Seal | |||||||||

| 19 | C3 | Carbonera C3 | Proximal fluvio-deltaic (C3) | Reservoir | |||||||||

| 21 | Early Miocene | Pebas wetlands | C4 | Carbonera C4 | Barzalosa | Distal fluvio-deltaic (C4) | Seal | ||||||

| 23 | Late Oligocene |  | Andean orogeny 1 Foredeep | C5 | Carbonera C5 | Orito | Proximal fluvio-deltaic (C5) | Reservoir | [8][11] | ||||

| 25 | C6 | Carbonera C6 | Distal fluvio-lacustrine (C6) | Seal | |||||||||

| 28 | Early Oligocene | C7 | C7 | Pepino | Gualanday | Proximal deltaic-marine (C7) | Reservoir | [8][11][13] | |||||

| 32 | Oligo-Eocene | C8 | Usme | C8 | onlap | Marine-deltaic (C8) | Seal Source | [13] | |||||

| 35 | Late Eocene |  | Mirador | Mirador | Coastal (Mirador) | 240 m (790 ft) (Mirador) | Reservoir | [10][14] | |||||

| 40 | Middle Eocene | Regadera | hiatus | ||||||||||

| 45 | |||||||||||||

| 50 | Early Eocene |  | Socha | Los Cuervos | Deltaic (Los Cuervos) | 260 m (850 ft) (Los Cuervos) | Seal Source | [10][14] | |||||

| 55 | Late Paleocene | PETM 2000 ppm CO2 | Los Cuervos | Bogotá | Gualanday | ||||||||

| 60 | Early Paleocene | SALMA | Barco | Guaduas | Barco | Rumiyaco | Fluvial (Barco) | 225 m (738 ft) (Barco) | Reservoir | [7][8][11][10][15] | |||

| 65 | Maastrichtian |  | KT extinction | Catatumbo | Guadalupe | Monserrate | Deltaic-fluvial (Guadalupe) | 750 m (2,460 ft) (Guadalupe) | Reservoir | [7][10] | |||

| 72 | Campanian | End of rifting | Colón-Mito Juan | [10][16] | |||||||||

| 83 | Santonian | Villeta/Güagüaquí | |||||||||||

| 86 | Coniacian | ||||||||||||

| 89 | Turonian | Cenomanian-Turonian anoxic event | La Luna | Chipaque | Gachetá | hiatus | Restricted marine (all) | 500 m (1,600 ft) (Gachetá) | Source | [7][10][17] | |||

| 93 | Cenomanian |  | Rift 2 | ||||||||||

| 100 | Albian | Une | Une | Caballos | Deltaic (Une) | 500 m (1,600 ft) (Une) | Reservoir | [11][17] | |||||

| 113 | Aptian |  | Capacho | Fómeque | Motema | Yaví | Open marine (Fómeque) | 800 m (2,600 ft) (Fómeque) | Source (Fóm) | [8][10][18] | |||

| 125 | Barremian | High biodiversity | Aguardiente | Paja | Shallow to open marine (Paja) | 940 m (3,080 ft) (Paja) | Reservoir | [7] | |||||

| 129 | Hauterivian |  | Rift 1 | Tibú- Mercedes | Las Juntas | hiatus | Deltaic (Las Juntas) | 910 m (2,990 ft) (Las Juntas) | Reservoir (LJun) | [7] | |||

| 133 | Valanginian | Río Negro | Cáqueza Macanal Rosablanca | Restricted marine (Macanal) | 2,935 m (9,629 ft) (Macanal) | Source (Mac) | [8][19] | ||||||

| 140 | Berriasian | Girón | |||||||||||

| 145 | Tithonian | Break-up of Pangea | Jordán | Arcabuco | Buenavista Batá | Saldaña | Alluvial, fluvial (Buenavista) | 110 m (360 ft) (Buenavista) | "Jurassic" | [11][20] | |||

| 150 | Early-Mid Jurassic |  | Passive margin 2 | La Quinta | Montebel Noreán | hiatus | Coastal tuff (La Quinta) | 100 m (330 ft) (La Quinta) | [21] | ||||

| 201 | Late Triassic |  | Mucuchachi | Payandé | [11] | ||||||||

| 235 | Early Triassic |  | Pangea | hiatus | "Paleozoic" | ||||||||

| 250 | Permian |  | |||||||||||

| 300 | Late Carboniferous |  | Famatinian orogeny | Cerro Neiva () | [22] | ||||||||

| 340 | Early Carboniferous | Fossil fish Romer's gap | Cuche (355-385) | Farallones () | Deltaic, estuarine (Cuche) | 900 m (3,000 ft) (Cuche) | |||||||

| 360 | Late Devonian |  | Passive margin 1 | Río Cachirí (360-419) | Ambicá () | Alluvial-fluvial-reef (Farallones) | 2,400 m (7,900 ft) (Farallones) | [19][23][24][25][26] | |||||

| 390 | Early Devonian |  | High biodiversity | Floresta (387-400) El Tíbet | Shallow marine (Floresta) | 600 m (2,000 ft) (Floresta) | |||||||

| 410 | Late Silurian | Silurian mystery | |||||||||||

| 425 | Early Silurian | hiatus | |||||||||||

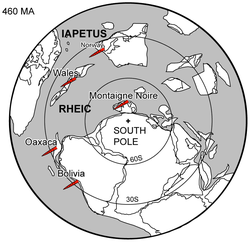

| 440 | Late Ordovician |  | Rich fauna in Bolivia | San Pedro (450-490) | Duda () | ||||||||

| 470 | Early Ordovician | First fossils | Busbanzá (>470±22) Chuscales Otengá | Guape () | Río Nevado () | Hígado () | [27][28][29] | ||||||

| 488 | Late Cambrian |  | Regional intrusions | Chicamocha (490-515) | Quetame () | Ariarí () | SJ del Guaviare (490-590) | San Isidro () | [30][31] | ||||

| 515 | Early Cambrian | Cambrian explosion | [29][32] | ||||||||||

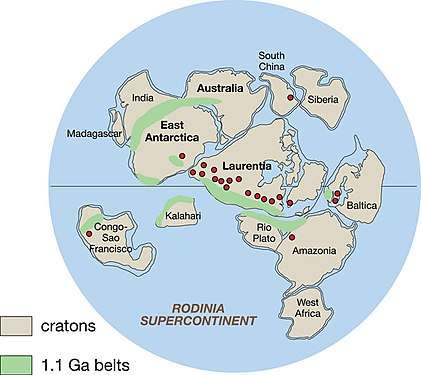

| 542 | Ediacaran |  | Break-up of Rodinia | pre-Quetame | post-Parguaza | El Barro () | Yellow: allochthonous basement (Chibcha Terrane) Green: autochthonous basement (Río Negro-Juruena Province) | Basement | [33][34] | ||||

| 600 | Neoproterozoic |  | Cariri Velhos orogeny | Bucaramanga (600-1400) | pre-Guaviare | [30] | |||||||

| 800 |  | Snowball Earth | [35] | ||||||||||

| 1000 | Mesoproterozoic |  | Sunsás orogeny | Ariarí (1000) | La Urraca (1030-1100) | [36][37][38][39] | |||||||

| 1300 | Rondônia-Juruá orogeny | pre-Ariarí | Parguaza (1300-1400) | Garzón (1180-1550) | [40] | ||||||||

| 1400 |  | pre-Bucaramanga | [41] | ||||||||||

| 1600 | Paleoproterozoic | Maimachi (1500-1700) | pre-Garzón | [42] | |||||||||

| 1800 |  | Tapajós orogeny | Mitú (1800) | [40][42] | |||||||||

| 1950 | Transamazonic orogeny | pre-Mitú | [40] | ||||||||||

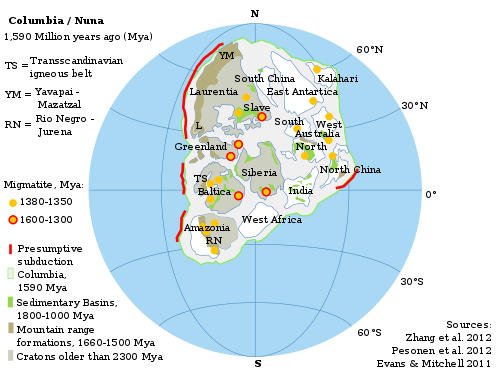

| 2200 | Columbia | ||||||||||||

| 2530 | Archean |  | Carajas-Imataca orogeny | [40] | |||||||||

| 3100 | Kenorland | ||||||||||||

| Sources | |||||||||||||

- Legend

- group

- important formation

- fossiliferous formation

- minor formation

- (age in Ma)

- proximal Llanos (Medina)[note 1]

- distal Llanos (Saltarin 1A well)[note 2]

See also

Notes

References

- Ayala, 2009, p.20

- Hernández Ferrer, 2011, p.47

- Ayala, 2009, p.21

- García González et al., 2007, p.68

- Plancha 34, 2007

- Plancha 48, 2008

- García González et al., 2009, p.27

- García González et al., 2009, p.50

- García González et al., 2009, p.85

- Barrero et al., 2007, p.60

- Barrero et al., 2007, p.58

- Plancha 111, 2001, p.29

- Plancha 177, 2015, p.39

- Plancha 111, 2001, p.26

- Plancha 111, 2001, p.24

- Plancha 111, 2001, p.23

- Pulido & Gómez, 2001, p.32

- Pulido & Gómez, 2001, p.30

- Pulido & Gómez, 2001, pp.21-26

- Pulido & Gómez, 2001, p.28

- Correa Martínez et al., 2019, p.49

- Plancha 303, 2002, p.27

- Terraza et al., 2008, p.22

- Plancha 229, 2015, pp.46-55

- Plancha 303, 2002, p.26

- Moreno Sánchez et al., 2009, p.53

- Mantilla Figueroa et al., 2015, p.43

- Manosalva Sánchez et al., 2017, p.84

- Plancha 303, 2002, p.24

- Mantilla Figueroa et al., 2015, p.42

- Arango Mejía et al., 2012, p.25

- Plancha 350, 2011, p.49

- Pulido & Gómez, 2001, pp.17-21

- Plancha 111, 2001, p.13

- Plancha 303, 2002, p.23

- Plancha 348, 2015, p.38

- Planchas 367-414, 2003, p.35

- Toro Toro et al., 2014, p.22

- Plancha 303, 2002, p.21

- Bonilla et al., 2016, p.19

- Gómez Tapias et al., 2015, p.209

- Bonilla et al., 2016, p.22

- Duarte et al., 2019

- García González et al., 2009

- Pulido & Gómez, 2001

- García González et al., 2009, p.60

Bibliography

- Ayala Calvo, Rosa Carolina. 2009. Análisis tectonoestratigráfico y de procedencia en la Subcuenca de Cesar: Relación con los sistemas petroleros (MSc. thesis), 1–255. Universidad Simón Bolívar. Accessed 2017-06-14.

- García González, Mario; Ricardo Mier Umaña; Luis Enrique Cruz Guevara, and Mauricio Vásquez. 2009. Informe Ejecutivo - evaluación del potencial hidrocarburífero de las cuencas colombianas, 1–219. Universidad Industrial de Santander.

- Hernández Ferrer, Mauricio Esteban. 2011. Actualización de la geología de superficie en la Sierra de Perijá mediante la utilización de imágenes satelitales, 1–125. Simón Bolívar University. Accessed 2017-08-03.

Maps

- Colmenares, Fabio; Milena Mesa; Jairo Roncancio; Edgar Arciniegas; Pablo Pedraza; Agustín Cardona; César Silva; Jhoamna Romero, and Sonia Alvarado and Oscar Romero, Felipe Vargas, Carlos Santamaría. 2007. Plancha 34 - Agustín Codazzi - 1:100,000, 1. INGEOMINAS. Accessed 2017-06-14.

- Hernández, Marina, and Jairo Clavijo. 2008. Plancha 48 - La Jagua de Ibirico - 1:100,000, 1. INGEOMINAS. Accessed 2017-06-14.