Puyehue-Cordón Caulle

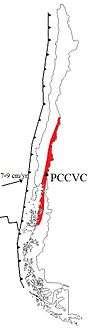

Puyehue (/pʊˈjeɪweɪ/; Spanish pronunciation: [puˈʝewe]) and Cordón Caulle /kɔːrˈdoʊn ˈkaʊjeɪ/ are two coalesced volcanic edifices that form a major mountain massif in Puyehue National Park in the Andes of Ranco Province, in the South of Chile. In volcanology this group is known as the Puyehue-Cordón Caulle Volcanic Complex (PCCVC). Four volcanoes constitute the volcanic group or complex, the Cordillera Nevada caldera, the Pliocene Mencheca volcano, Cordón Caulle fissure vents and the Puyehue stratovolcano.[3]

| Puyehue-Cordón Caulle | |

|---|---|

Puyehue Volcano as seen from the south side of Puyehue Lake | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 2,236 m (7,336 ft) (Puyehue)[1] |

| Coordinates | 40°35′25″S 72°07′02″W (Puyehue) |

| Naming | |

| Language of name | Puyehue means place of small fishes in Mapudungun |

| Geography | |

| Location | Lago Ranco, Río Bueno and Puyehue communes, Chile |

| Parent range | Andes |

| Geology | |

| Mountain type | Complex volcano |

| Volcanic arc/belt | Southern Volcanic Zone |

| Last eruption | 2011 to 2012[2] |

| Climbing | |

| Easiest route | Entre Lagos – Fundo El Caulle – Puyehue's peak |

Like most stratovolcanoes in the Southern Volcanic Zone of the Andean Volcanic Belt, Puyehue and Cordón Caulle are along the intersection of a traverse fracture with the larger north-south Liquiñe-Ofqui Fault. The volcanic complex has shaped the local landscape and produced a huge variety of volcanic landforms and products over the last 300,000 years. Cinder cones, lava domes, calderas and craters can be found in the area apart from the widest variety of volcanic rocks in all the Southern Zone,[4] for example both primitive basalts and rhyolites. Cordón Caulle erupted shortly after the 1960 Valdivia earthquake, the largest recorded earthquake in history.[5]

Apart from this, the Puyehue-Cordón Caulle area is one of the main sites of exploration for geothermal power in Chile.[6][7] Geothermal activity is manifested on the surface of Puyehue and Cordón Caulle as several boiling springs, solfataras and fumaroles.[8]

Most of the stone artifacts found in Pilauco Bajo (dated to c. 12.5 to 13.5 ka BP) are made of dacite, rhyodacite and rhyolite from the Puyehue-Cordón Caulle. Yet these rocks were imported by humans to the site as nearby rivers have not transported it.[9]

Approach and ascent

From the south, the Cordón Caulle can be approached from Fundo El Caulle on Route 215-CH, which goes from Osorno to Bariloche in Argentina through Samoré Pass. Some 1,000 m up on forested slope there is a campsite and mountain shelter. According to the homepage of Puyehue National Park the shelter can be reached after four hours walking.[10] The access through El Caulle is not public as it is not inside Puyehue National Park; and an entrance fee of 10,000 CLP, as of 2009, has to be paid, of which 3,000 are refunded if visitor packs out his garbage.[11] From the north, there are tracks from the vicinities of Nilahue Valley near Ranco Lake. The track ascends ca 1,000 m through dense forest to the Cordón Caulle area. From the relatively flat Cordón Caulle there is further ca 600 m of ascent over tephra and loose rocks to the summit of Puyehue. In the Nilahue area there are arrieros who offer horseback trips to Cordón Caulle.

Geography

Puyehue, Cordón del Caulle, and Cordillera Nevada form a northwest trending massif in the Ranco Province of the Andes. The three volcanoes are coalesced. Puyehue is located in the southeast, Cordón Caulle in the center, and Cordillera Nevada, which owes its name to its often snowy appearance from the relatively densely populated Chilean Central Valley, is at the northwestern end. The massif is located between two lakes, Ranco Lake in the north and Puyehue Lake in the south. The fact that Puyehue volcano is named after Puyehue Lake reflects that it is better seen and more accessible from the south. Cordillera Nevada is a 9-kilometre (6 mi) wide semicircular caldera and corresponds to the remnants of a collapsed volcano. Cordillera Nevada covers an area of 700 square kilometres (270 sq mi). Cordón Caulle is a northwest trending ridge that hosts a volcanic-tectonic graben in which a fissure vent is developed. Puyehue Volcano is a stratovolcano located on the southeastern end of Cordón Caulle, just east of the main fault of the Liquiñe-Ofqui Fault Zone. Its cone hosts a 2.4 km (1.5 mi) wide crater, and products of Puyehue volcanism cover an approximate area of 160 km2 (62 sq mi).[1]

Flora

The lower parts of the mountains are covered by an alpine plant association of Valdivian temperate rainforest, where plant species such as Chusquea coleou and Nothofagus dombeyi are common. The tree line, lying around 1,500 m (4,921 ft) elevation, is mostly made up of Nothofagus pumilio.[12] Above this line lies a volcanic desert and alpine tundras. The main plant species present in these high elevations are Gaultheria mucronata, Empetrum rubrum, Hordeum comosun and Cissus striata.[13]

Geologic history

The volcanic complex that comprises Puyehue, Cordón Caulle and Cordillera Nevada[5] has a long record of active history spanning from 300,000 years ago to the present. The older parts of the Cordillera Nevada caldera and Mencheca volcano reflect even older activity from the Pliocene or the early Pleistocene.[14] In the past 300,000 years, there have been a series of changes in magmatic composition, locus of volcanic activity, magma output rates and eruptive styles.

Ancestral volcanoes

Some 300,000 years ago, important changes occurred in the area of Puyehue. The old Pliocene volcano Mencheca, currently exposed just northeast of Puyehue's cone, declined in activity. This decline was probably due a regional change in the location of the active front of the Southern Volcanic Zone that also affected other volcanoes such as Tronador and Lanín. The relocation of the active front gave rise to new volcanoes further westward or increased their activity. The formerly broad magmatic belt narrowed, retaining vigorous activity only in its westernmost parts. Associated with these changes are the oldest rocks of PCCVC, those that belong to Sierra Nevada. Sierra Nevada grew over time to form a large shield volcano, during the same time Cordón Caulle was also being built up having rather silicic products compared to coeval Sierra Nevada and Mencheca. The oldest rocks from proper Puyehue volcano are 200,000 years old, representing the youngest possible age for this volcano.

It is estimated that some 100,000 years ago in the period between Río Llico and Llanquihue glaciation a large ignimbrite called San Pablo was produced. This ignimbrite covers an estimated area of 1,500 square kilometres (370,658 acres) immediately west of Cordillera Nevada, stretching across the Chilean Central Valley almost reaching the Chilean Coast Range. The San Pablo ignimbrite has been associated with the formation of the Cordillera Nevada Caldera.

Volcanism during the Llanquihue glaciation

During the Llanquihue glaciation volcanism occurred on all three vents, Cordillera Nevada, Cordón Caulle and Puyehue volcano. During most of this time the volcano was covered by the Patagonian Ice Sheet, leaving glacial striae on many lava outcrops and affecting the volcanic activity.

In Cordillera Nevada this volcanism was expressed from about 117,000 years ago primarily as dacitic lava flows erupted along ring faults. These lava flows partly filled the caldera and flowed north, out to what is now Nilahue River. In mid or late glacial times cordillera Nevada produced its last lavas which were andesitic to dacitic in composition. Cordón Caulle evolved during this time from being a shield volcano to a graben with fissure vents. This was accompanied by emission of ignimbrites and dacitic lava flows.

Puyehue was characterized by eruption of basaltic andesites to dacites until its activity turned bimodal at around 34,000 years ago. The onset of this change was marked by the eruption of rhyodacite mingled with basaltic andesite rich in magnesium oxide (MgO). The bimodal activity continued with a small hiatus around 30,000 years ago until around 19,000 years ago when Puyehues started to produce lava domes and flows of dacitic to rhyolitic composition, a trend that lasted until 12,000 years before present. Between 15,000 and 12,000 years ago Puyehue also erupted basaltic andesite. During the Llanquihue glaciation Puyehue volcano produced some of the most primitive basalts of the Southern Volcanic Zone with a magnesium oxide mass percentage of 14.32, which is in equilibrium with melt from mantle peridotite.[4]

Postglacial volcanism

Only Puyehue and Cordón Caulle have erupted during the Holocene, and until 2011 only Cordón Caulle had recorded historical eruptions. In the interval between 7,000 and 5,000 years ago Puyehue had rhyolitic eruptions that produced lava domes. The lava domes were later destroyed after a sequence of strong eruptions that were part of an explosive eruptive cycle. These last eruptions were likely of phreatomagmatic and sub-plinian type and occurred around 1,100 years ago (~850 CE).[15]

Recent eruptions

Eruptive records in Cordón Caulle, the only active centre in the Puyehue-Cordón Caulle system in historical times, are relatively scarce. This is explained by the geographical position of Cordón Caulle and the history of Spanish and Chilean settlement in southern Chile. After a failed attempt in 1553, governor García Hurtado de Mendoza founded the city of Osorno in 1558, the only Spanish settlement in the zone, 80 kilometres (50 mi) west of Cordón Caulle. This settlements had to be abandoned in 1602 due to conflicts with native Huilliches. No eruption record is known from this era. From 1602 to the mid-18th century there were no Spanish settlements within a radius of 100 kilometres (62 mi). The closest were Valdivia and the sporadic missions of Nahuel Huapi all of them out of sight of the volcano. In 1759 an eruption was noticed in the Cordillera, although this is mainly attributed to Mocho. By the end of the 19th century most of the Central Valley west of Cordón Caulle had been settled by Chileans and European immigrants and an eruption was reported in 1893. The next report came in 1905, but the eruption of 8 February 1914 is the first one certain to have occurred.

| Year | Date | VEI | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 4 June | 5 | 2011 Cordón Caulle eruption |

| 1990 | 1 | A small pumice cone in Cordón Caulle is believed to have formed | |

| 1960 | 24 May | 3 | Following the 1960 Valdivia earthquake whose main shock came on 22 May 1960, Cordón Caulle started to erupt along its southern flank. |

| 1934 | 6 March | 2 | Puyehue-Cordón Caulle erupted |

| 1929 | 7 January | 2 | Puyehue-Cordón Caulle erupted |

| 1921 | 13 December | 3 | Cordón Caulle had a sub-plinian eruption, with a 6.2 kilometres (4 mi) high plume, periodic explosions and seismicity. Ended in February 1922. |

| 1919 | 2 | Puyehue-Cordón Caulle started an eruption that lasted until 1920. | |

| 1914 | 8 February | 2 | Puyehue-Cordón Caulle erupted |

| 1905 | 2 | Puyehue-Cordón Caulle might have erupted | |

| 1893 | 2 | Puyehue-Cordón Caulle might have erupted | |

| 1759 | 2 | Puyehue-Cordón Caulle might have erupted |

1921–1922, 1929 and 1934 eruptions

On 13 December 1921, Cordón Caulle began a sub-plinian eruption, with a 6.2 kilometres (4 mi) high plume, periodic explosions and seismicity. The eruption had a Volcanic Explosivity Index of 3 and ended on February 1922. In 1929 and 1934 the Cordón Caulle had fissure eruptions, both with an estimated Volcanic Explosivity Index of 2.

1960 eruption

Two days after the main shock of the 1960 Valdivia earthquake, the largest earthquake recorded in history, Cordón Caulle erupted.[17] The eruption was believed to have been caused by the earthquake.[17] The earthquake had struck the whole of Chile between Talca (30°S) and Chiloé (43°S) and had an estimated moment magnitude of 9.5. Being located between two sparsely populated and by then isolated Andean valleys the eruption had few eyewitnesses and received little attention by local media due to the huge damages and losses caused by the main earthquake.[5] The eruption was fed by a 5.5 kilometres (3 mi) long and north west-west (N135°) trending fissure along which 21 individual vents have been found. These vents produced an output of about 0.25 km³ DRE both in form of lava flows and tephra.

The eruption began in a sub-plinian style creating a column of volcanic gas, pyroclasts and ash about 8 km in height. The erupting N135° trending fissure had two craters of major activity emplaced at each end; the Gris Crater and El Azufral Crater. Volcanic vents of Cordón Caulle that were not in eruption produced visible steam emissions. After this explosive phase the eruption changed character to a more effusive one marked by rhyodacitic blocky and Aa type lava flows emitted from the vents along the N135° trending fissure. A third phase followed with the appearance of short north-north west (N165°) oriented vents transverse to the main fissure which also erupted rhyodacitic lava. The third phase ended temporarily with viscous lava obstructing the vents, but continued soon with explosive activity restricted to the Gris and El Azufral craters. The eruption came to an end on 22 July.[5]

1960–2011 period

Following the end of the 1960 eruption, Cordón Caulle has remained relatively quiet if compared with the first half of the 20th century. On 2 March 1972 there was a report of an eruption west of Bariloche in Argentina. The Chilean emergency office ONEMI (Oficina Nacional de Emergencia del Ministerio del Interior) organized a flight over the area with two volcanologists aboard. Puyehue and Cordón Caulle as well the Carrán crater were found without activity.[18][19] From accounts of local inhabitants of the area it is inferred that a small pumice cone was formed around 1990. In 1994 a temporarily emplaced seismic network registered tremors north of Puyehue's cone which reached IV and V degrees on the Mercalli intensity scale. This prompted ONEMI to invoke an emergency action committee, however soon afterward unrest ceased.[1] Between 4 and 17 May 2011 seismic activity partly attributed to the movements of fluids was detected Southern Andean Volcano Observatory (OVDAS). The activity concentrated around and in Cordillera Nevada caldera and on western Cordón Caulle. This prompted SERNAGEOMIN-OVDAS to declare yellow alert.[20]

2011–2012 eruption

A new eruption started on 4 June 2011. By the 4th 3,500 people had been evacuated from nearby areas,[22] while an ash cloud reaching 12,000 metres (39,370 ft).[23] blew toward the city of Bariloche, Argentina, where the local airport was closed.[24] At approximately 16:30 local time, Neuquén airport further east in Argentina was also closed due to the ash cloud. Airports as far away as Buenos Aires and Melbourne, Australia, had to be closed temporarily due to volcanic ash.[25][26][27]

By 15 June a dense column of ash was still erupting 10 km into the air, with the ash cloud spreading across the Southern Hemisphere;[28] scientists expected intensifying eruptions of Puyehue in the following days, and said the volcano showed no signs of slowing down.[29][30]

Geothermal activity and exploration

Cordón Caulle is a major area of geothermal activity,[6] as manifested by the several hot springs, boiling springs, solfataras and fumaroles that develop on it. The geothermal system in Cordón Caulle consists of a vapour dominated system overlain by a more superficial steam heated aquifer.[7] The temperatures of the vapour systems range from 260–340 °C (500-680 °F) and 150–180 °C (302-356 °F) for the aquifer.[8] The uppermost part of the geothermal system, at 1500–2000 m (4,921–6,562 ft), is characterized by fumaroles and acid-sulfate springs.[7] Cordón Caulle is considered one of the main sites of geothermal exploration in Chile.[6]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cordón Caulle. |

References

- Lara, L. E.; H. Moreno, J. A. Naranjo, S. Matthews, C. Pérez de Arce (2006). "Magmatic Evolution of the Puyehue-Cordón Caulle Volcanic Complex (40° S), Southern Andean Volcanic Zone: From shield to unusual fissure volcanism". Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research. 157 (4): 343–366. Bibcode:2006JVGR..157..343L. doi:10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2006.04.010.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "Servicio Nacional de Geología y Minería" (PDF) (in Spanish). Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 June 2011.

- Gerlach, David C.; Frederick A. Frey, Hugo Moreno-Roa, Leopoldo López-Escobar, Stasiuk1, S. J. Lane, C. R. Adam, M. D. Murphy, R. S. J. Sparks and J. A. Naranjo (1988). "Recent Volcanism in the Puyehue-Cordon Caulle Region, Southern Andes, Chile (40.5° S): Petrogeneis of Evolved Lavas". Journal of Petrology. 58 (2): 67–83. Bibcode:1988JPet...29..333G. doi:10.1093/petrology/29.2.333.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Leopoldo López-Escobar; Hugo Moreno-Roa (1994). "Geochemical Characteristics of the Southern andes Basaltic Volcanism Associated with the Liquiñe-Ofqui Fault between 39° and 46° S" (PDF). 7° Congreso Geológico Chileno. Actas. n II: 1388–1393. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 June 2007. Retrieved 25 April 2009.

- Lara, L.E., Naranjo J.A., Moreno, H. "Rhyodacitic fissure eruption in Southern Andes (Cordón Caulle; 40.5°S) after the 1960 (Mw:9.5) Chilean earthquake: a structural interpretation". Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research. vol 138. 2004.

- Lahsen, Alfredo; Sepúlveda, Fabián; Rojas, Juan; Palacios, Carlos (2005), Present Status of Geothermal Exploration in Chile (PDF), Proceedings World Geothermal Congress 2005: Antalya, Turkey, 24–29 April 2005

- Dorsch, Klaus (2003), Hydrogeologische Untersuchungen der Geothermalfelder von Puyehue und Cordón Caulle, Chile. (PDF), PhD-Thesis, Ludwig-Maximilians University Munich (LMU), Geo-Department, in German with English and Spanish abstracts.

- Sepúlveda, Fabián; Lahsen, Alfredo; Dorsch, Klaus; Palacios, Carlos and Bender, Steffen. Geothermal Exploration in the Cordón Caulle Region, Southern Chile. Proceedings World Geothermal Congress 2005.

- Navarro-Harris, Ximena; Pino, Mario; Guzmán‐Marín, Pedro; Lira, María Paz; Labarca, Rafael; Corgne, Alexandre (2 March 2019). "The procurement and use of knappable glassy volcanic rawmaterial from the late Pleistocene Pilauco site, ChileanNorthwestern Patagonia". Geoarchaeology. doi:10.1002/gea.21736.

- SENDEROS SECTOR ANTICURA, Puyehue National Park. Retrieved 11 December 2009.

- McCarthy, Carolyn (2009). Lonely Planet: Trekking in the Patagonian Andes. p. 90.

- Lori D Daniels, Thomas T Veblen. Altitudinal treelines of the southern Andes near 40ºS. The Forestry Chronicle, 2003, 79:237–241

- "Flora". Puyehue National Park. Archived from the original on 9 June 2011. Retrieved 25 October 2009.

- Lara, L., Rodríguez C., Moreno, H. and Pérez de Arce, C. Geocronología K-Ar y geoquímica del volcanismo plioceno superior-pleistoceno de los Andes del sur (29–42°S). Revista Geológica de Chile, July 2001.

- Singer, Brad S., Jicha, Brian R., Harper. Melissa A., Naranjo, José A., Lara, Luis E., Moreno-Roa, Hugo. Eruptive history, geochronology, and magmatic evolution of the Puyehue-Cordón Caulle volcanic complex, Chile. GSA Bulletin. 2008.

- Reporte Especial de Actividad Volcánica No 28 Archived 27 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Región de Los Ríos, Complejo Volcánico Puyehue – Cordón Caulle, 4 June 2011. Hora del reporte: 15:15 hora local. SERNAGEOMIN and OVDAS.

- Pallardy, Richard (17 August 2018). "Chile earthquake of 1960". Encyclopaedia Britannica Online. Archived from the original on 15 September 2018. Retrieved 14 September 2018.

- El Correo: Volcán Puyehue Archived 18 September 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- "Spanish language report of green alert status in march 2010" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 7 July 2011.

- Reporte No. 21 Actividad volcánica REGIÓN DE LOS RIOS: Mayo de 2011. OVDAS-SERNAGEOMIN.

- NASA - Puyehue-Cordón Caulle

- Volcán Puyehue: Gobierno evacua a 3.500 personas Archived 6 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine La Nacion, 4 June 2011 (in Spanish)

- "Puyehue volcano (Chile), activity update: continuous ash eruptions reaching 10–12 km". Volcanodiscovery.com. 6 June 2011. Retrieved 7 July 2011.

- Bariloche entró en alerta roja por las cenizas del volcán chileno Puyehue Archived 8 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine MDZ online, 4 June 2011 (in Spanish)

- "Volcanic Ash from Puyehue Halts Argentina's Air Traffic Again Today". International Business Times. 9 June 2011. Retrieved 9 June 2011.

- "Puyehue's volcanic ash cloud grounds flights out of Argentine capital". CNN. Retrieved 9 June 2011.

- Critchlow, Andrew; Craymer, Lucy (11 June 2011). "Ash Disrupts Flights in Australia, New Zealand". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 12 June 2011.

- "Puyehue-Cordón Caulle volcano (Chile): strong ash emissions and incandescence at night". Volcanodiscovery.com. 15 June 2011. Retrieved 7 July 2011.

- "NASA – NASA Satellite Gallery Shows Chilean Volcano Plume Moving Around the World". Nasa.gov. Retrieved 7 July 2011.

- "Chilean eruption shows no sign of abating | euronews, world news". Euronews.net. 15 June 2011. Retrieved 7 July 2011.