Old Prussians

Old Prussians, Baltic Prussians or simply Prussians (Old Prussian: Prūsai; German: Pruzzen or Prußen; Latin: Pruteni; Latvian: Prūši; Lithuanian: Prūsai; Polish: Prusowie; Kashubian: Prësowié) were the indigenous peoples from a cluster of Baltic tribes that inhabited the region of Prussia. This region lent its name to the later state of Prussia (see King in Prussia). It was located on the south-eastern shore of the Baltic Sea between the Vistula Lagoon to the west and the Curonian Lagoon to the east. The people spoke a language now known as Old Prussian and followed pagan Prussian mythology.

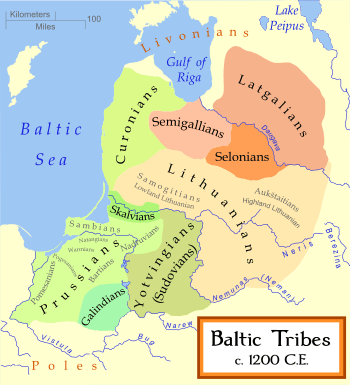

The Prussian tribes in the context of the other Baltic tribes, ca. 1200 AD. The Eastern Balts are shown in brown hues whereas the Western Balts are shown in green. The boundaries are approximate. |

During the 13th century, the Old Prussians were conquered by the Teutonic Order. The former German state of Prussia took its name from the Baltic Prussians, although it was led by Germans. The Teutonic Knights and their troops transferred the Baltic Prussians from southern Prussia to northern Prussia. Many Old Prussians were also killed in crusades requested by Poland and the popes, while others were assimilated and converted to Christianity. The old Prussian language was extinct by the 17th or early 18th century.[1] Many Old Prussians emigrated due to Teutonic crusades.[2]

The land of the Old Prussians was larger before the arrival of the Polans, consisting of central and southern East Prussia and West Prussia. In post 1945 terms, the Old Prussian territory is equivalent to the modern areas of Warmian-Masurian Voivodeship (in Poland), the Kaliningrad Oblast (in Russia) and the southern Klaipėda Region (of Lithuania). The territory was also inhabited by Scalovians, a tribe related to the Prussians, Curonians, and Eastern Balts.

Etymology

The names of the Baltic Prussian tribes all reflected the theme of landscape. Most of the names were based on water, an understandable convention in a land dotted with thousands of lakes, streams, and swamps (the Masurian Lake District). To the south, the terrain runs into the Pripet Marshes at the headwaters of the Dnieper River; these have been an effective barrier over the millennia.

History of Brandenburg and Prussia | ||||

| Northern March 965–983 |

Old Prussians pre-13th century | |||

| Lutician federation 983 – 12th century | ||||

| Margraviate of Brandenburg 1157–1618 (1806) (HRE) (Bohemia 1373–1415) |

Teutonic Order 1224–1525 (Polish fief 1466–1525) | |||

| Duchy of Prussia 1525–1618 (1701) (Polish fief 1525–1657) |

Royal (Polish) Prussia (Poland) 1454/1466 – 1772 | |||

| Brandenburg-Prussia 1618–1701 | ||||

| Kingdom in Prussia 1701–1772 | ||||

| Kingdom of Prussia 1772–1918 | ||||

| Free State of Prussia (Germany) 1918–1947 |

Klaipėda Region (Lithuania) 1920–1939 / 1945–present |

Recovered Territories (Poland) 1918/1945–present | ||

| Brandenburg (Germany) 1947–1952 / 1990–present |

Kaliningrad Oblast (Russia) 1945–present | |||

The original pre-Baltic settlers generally named their settlements after the streams, lakes, seas, or forests by which they settled. The clan or tribal entities into which they were organized then took the name of the settlement.

This root is perhaps the one used in the very name of Prusa (Prussia), for which an earlier Brus- is found in the map of the Bavarian Geographer. In Tacitus' Germania, the Lugii Buri are mentioned living within the eastern range of the Germans. Lugi may descend from Pokorny's *leug- (2), "black, swamp" (Page 686), while Buri is perhaps the "Prussian" root.

The name of Pameddi (Pomesania) tribe is derived from the words pa ("by" or "near") and meddin ("forest") or meddu ("honey").[3] Nadruvia may be a compound of the words na ("by" or "on") and drawē ("wood") or nad ("above") and the root *reu- ("flow" or "river"). The name of the Bartians, a Prussian tribe, and the name of the Bārta river in Latvia are possibly cognates.

In the 2nd century AD, the geographer Claudius Ptolemy listed some Borusci living in European Sarmatia (in his Eighth Map of Europe), which was separated from Germania by the Vistula Flumen. His map is very confused in that region, but the Borusci seem further east than the Prussians, which would have been under the Gythones (Goths) at the mouth of the Vistula. The Aesti (Easterners), recorded by Tacitus, were 450 years later recorded by Jordanes as part of the Gothic Empire.

Organization

At the beginning of Baltic history, the Old Prussians were bordered by the Vistula and the Memel – earlier Mimmel – river, which outside of Prussia is called Neman, with a southern depth to about Thorn at the Vistula river, which was Prussian, and the line of the river Narew. The Kashubians and Pomeranians were by the year AD 1000 on the west, the Poles on the south, the Sudovians (sometimes considered a separate people, other times regarded as a Prussian tribe) on the east and further south, the Skalvians on the north, and the Lithuanians on the northeast. The Sudovians began at about Suwałki.

At the end of the 1st century, Prussian settlements were probably divided into tribal domains, separated from one another by uninhabited areas of forest, swamp and marsh. A basic territorial community was perhaps called a laūks, a word attested in Old Prussian as "field".[4] This word appears as a segment in Baltic settlement names, especially Curonian,[5] and it is found in Old Prussian placenames such as Stablack, from stabs (stone) + laūks (field, thus stone field). The plural is not attested in Old Prussian, but the Lithuanian plural of laukas ("field") is laukai.

A laūks was formed by a group of farms, which shared economic interests and a desire for safety. The supreme power resided in general gatherings of all adult males, who discussed important matters concerning the community and elected the leader and chief; the leader was responsible for the supervision of the everyday matters, while the chief (the rikīs) was in charge of the road and watchtower building, and border defense, undertaken by Vidivarii.

The term laūks must have included the fortifications, if any, and the social superstructure, but the village itself went by another name: kāims.[6] The head of a household was the buttataws (literally, the house father, from buttan, meaning home, and taws, meaning father).

Because the Baltic tribes inhabiting Prussia never formed a common political and territorial organisation, they had no reason to adopt a common ethnic or national name. Instead they used the name of the region from which they came — Galindians, Sambians, Bartians, Nadruvians, Natangians, Scalovians, Sudovians, etc. It is not known when and how the first general names came into being. This lack of unity weakened them severely, similar to the condition of Germany during the Middle Ages.

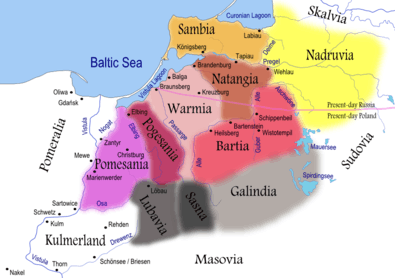

The Prussian tribal structure is most fully attested in the Chronicon terrae Prussiae of Peter of Dusburg, a priest of the Teutonic Order. The work is dated to 1326. He lists eleven lands and ten tribes, which were named on a geographical basis. These were:

| Latin | German | modern Lithuanian | reconstructed Prussian | see also | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pomesania | Pomesanien | Pamedė | Pameddi | Pomesanians |

| 2 | Varmia | Ermland, Warmien | Varmė | Wārmi | Warmians |

| 3 | Pogesania | Pogesanien | Pagudė | Paguddi | Pogesanians |

| 4 | Natangia | Natangen | Notanga | Notangi | Natangians |

| 5 | Sambia | Samland | Semba | Semba | Sambians |

| 6 | Nadrovia | Nadrauen | Nadruva | Nadrāuwa | Nadruvians |

| 7 | Bartia | Barten | Barta | Barta | Bartians |

| 8 | Scalovia | Schalauen | Skalva | Skallawa | Skalvians |

| 9 | Sudovia | Sudauen | Sūduva | Sūdawa | Sudovians, Yotvingians |

| 10 | Galindia | Galindien | Galinda | Galinda | Galindians |

| 11 | Culm | Kulmerland | Kulmas | Kulmus |

The Voyages of Ohthere and Wulfstan (in Anglo-Saxon) (English translation) describes a voyage by a Norseman called Wulfstan to the land of the Old Prussians, to the area around Elbing; he describes their funeral customs.

History

Cassiodorus' Variae, published in 537, contains a letter written by Cassiodorus in the name of Theodoric the Great, addressed to the Aesti:

- It is gratifying to us to know that you have heard of our fame, and have sent ambassadors who have passed through so many strange nations to seek our friendship.

We have received the amber which you have sent us. You say that you gather this lightest of all substances from the shores of ocean, but how it comes thither you know not. But as an author named Cornelius (Tacitus) informs us, it is gathered in the innermost islands of the ocean, being formed originally of the juice of a tree (whence its name succinum), and gradually hardened by the heat of the sun. Thus it becomes an exuded metal, a transparent softness, sometimes blushing with the color of saffron, sometimes glowing with flame-like clearness. Then, gliding down to the margin of sea, and further purified by the rolling of the tides, it is at length transported to your shores to be cast upon them. We have thought it better to point this out to you, lest you should imagine that your supposed secrets have escaped our knowledge. We sent you some presents by our ambassadors, and shall be glad to receive further visits from you by the road which you have thus opened up, and to show you future favors.

The Aesti are called Brus by the Bavarian Geographer in the 9th century.

More extensive mention of the Old Prussians in historical sources is in connection with Adalbert of Prague, who was sent by Bolesław I of Poland. Adalbert was slain in 997 during a missionary effort to Christianize the Prussians.[7] As soon as the first Polish dukes had been established with Mieszko I in 966, they undertook a number of conquests and crusades not only against Prussians and the closely related Sudovians, but against the Pomeranians and Wends as well.[8]

Beginning in 1147, the Polish duke Bolesław IV the Curly (securing the help of Ruthenian troops) tried to subdue Prussia, supposedly as punishment for the close cooperation of Prussians with Władysław II the Exile. The only source is unclear about the results of his attempts, vaguely only mentioning that the Prussians were defeated. Whatever were the results, in 1157 some Prussian troops supported the Polish army in their fight against Emperor Frederick Barbarossa. In 1166 two Polish dukes, Bolesław IV and his younger brother Henry, came into Prussia, again over the Ossa River. The prepared Prussians led the Polish army, under leadership of Henry, into an area of marshy morass. Whoever did not drown was felled by an arrow or by throwing clubs, and nearly all Polish troops perished. From 1191–93 Casimir II the Just invaded Prussia, this time along the river Drewenz (Drwęca). He forced some of the Prussian tribes to pay tribute, and then withdrew.

Several attacks by Konrad of Masovia in the early 13th century were also successfully repelled by the Prussians. In 1209 Pope Innocent III commissioned the Cistercian monk Christian of Oliva with the conversion of the pagan Prussians. In 1215, Christian was installed as the first bishop of Prussia. The Duchy of Masovia, and especially the region of Culmerland, become the object of constant Prussian counter-raids. In response, Konrad I of Masovia called on the Pope for aid several times, and founded a military order (the Order of Dobrzyń) before calling on the Teutonic Order. The results were edicts calling for Northern Crusades against the "marauding, heathen" Prussians.

In 1224, Emperor Frederick II proclaimed that he himself and the Empire took the population of Prussia and the neighboring provinces under their direct protection; the inhabitants were declared to be Reichsfreie, to be subordinated directly to the Church and the Empire only, and exempted from service to and the jurisdiction of other dukes. The Teutonic Order, officially subject directly to the Popes, but also under the control of the empire, took control of much of the Baltic, establishing their own monastic state in Prussia.

In 1230, following the Golden Bull of Rimini, Grand Master Hermann von Salza and Duke Konrad I of Masovia launched the Prussian Crusade, a joint invasion of Prussia to Christianise the Baltic Old Prussians. The Order then created the independent Monastic State of the Teutonic Knights in the conquered territory, and subsequently conquered Courland, Livonia, and Estonia. The Dukes of Poland accused the Order of holding lands illegally.

During an attack on Prussia in 1233, over 21,000 crusaders took part, of which the burggrave of Magdeburg brought 5,000 warriors, Duke Henry of Silesia 3,000, Duke Konrad of Masovia 4,000, Duke Casimir of Kuyavia 2,000, Duke Wladislaw of Greater Poland 2,200 and Dukes of Pomerania 5,000 warriors. The main battle took place at the Sirgune River and the Prussians suffered a decisive defeat. The Prussians took the bishop Christian and imprisoned him for several years.

Numerous knights from throughout Catholic Europe joined in the Prussian Crusades, which lasted sixty years. Many of the native Prussians from Sudovia who survived were resettled in Samland; Sudauer Winkel was named after them. Frequent revolts, including a major rebellion in 1286, were defeated by the Teutonic Knights. In 1283, according to the chronicler of the Teutonic Knights, Peter of Dusburg, the conquest of the Prussians ended and the war with the Lithuanians began.

In 1243, papal legate William of Modena divided Prussia into four bishoprics — Culm, Pomesania, Ermland, and Samland — under the Bishopric of Riga. Prussians were baptised at the Archbishopric of Magdeburg, while Germans and Dutch settlers colonized the lands of the native Prussians; Poles and Lithuanians also settled in southern and eastern Prussia, respectively. Significant pockets of Old Prussians were left in a matrix of Germans throughout Prussia and in what is now the Kaliningrad Oblast.

The monks and scholars of the Teutonic Order took an interest in the language spoken by the Prussians, and tried to record it. In addition, missionaries needed to communicate with the Prussians in order to convert them. Records of the Old Prussian language therefore survive; along with little-known Galindian and better-known Sudovian, these records are all that remain of the West Baltic language group. As might be expected, it is a very archaic Baltic language.

Old Prussians resisted the Teutonic Knights, and received help from the Grand Duchy of Lithuania during the 13th century in their quest to free themselves of the military order. In 1525 Grand Master Albert of Brandenburg-Ansbach secularized the Order's Prussian territories into the Protestant Duchy of Prussia, a vassal of the crown of Poland. During the Reformation, Lutheranism spread throughout the territories, officially in the Duchy of Prussia and unofficially in the Polish province of Royal Prussia, while Catholicism survived in the Prince-Bishopric of Warmia, the territory of secular rule comprising a third of the then Diocese of Warmia. With Protestantism came the use of the vernacular in church services instead of Latin, so Albert had the Catechisms translated into Old Prussian.

Because of the conquest of the Old Prussians by Germans, the Old Prussian language probably became extinct in the beginning of the 18th century with the devastation of the rural population by plagues and the assimilation of the nobility and the larger population with Germans or Lithuanians. However, translations of the Bible, Old Prussian poems, and some other texts survived and have enabled scholars to reconstruct the language.

Notes

- "Old Prussian language". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Meddu can be traced to the Proto-Indo-European root *medhu-.

- "Lie - Mikkels Klussis" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 October 2010. Retrieved 20 September 2018.

- It has various spellings, including -laukas, -laukis, and lauks.

- Attested in manuscripts as Caymis, and from the same PIE root as the modern German Keim and Heim (Middle High German kaim and haim), meaning sprout and home. The root is *tkei- (to settle) for both, from which English acquired the word home.

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Recent Issues in Polish Historiography of the Crusades Archived 2007-11-28 at the Wayback Machine Darius von Güttner Sporzyński. 2005