Prussian Reform Movement

The Prussian Reform Movement was a series of constitutional, administrative, social and economic reforms early in the nineteenth-century Kingdom of Prussia. They are sometimes known as the Stein-Hardenberg Reforms, for Karl Freiherr vom Stein and Karl August von Hardenberg, their main initiators. Before the Second World War, German historians, such as Heinrich von Treitschke, saw the reforms as the first steps towards the unification of Germany and the foundation of the German Empire.[1]

.jpg)

The reforms were a reaction to the defeat of the Prussians by Napoleon I at Jena-Auerstedt in 1806, leading to the second Treaty of Tilsit, in which Prussia lost about half its territory and was forced to make massive tribute payments to France. To make those payments, it needed to rationalize its administration. Prussia's defeat and subjection also demonstrated the weaknesses of its absolute monarchy model of statehood and excluded it from the great powers of Europe.

To become a great power again, it initiated reforms from 1807 onwards, based on Enlightenment ideas and in line with reforms in other European nations. They led to the reorganization of Prussia's government and administration and changes in its agricultural trade regulations, including the abolition of serfdom and allowing peasants to become landowners. In industry, the reforms aimed to encourage competition by suppressing the monopoly of guilds. The administration was decentralised and the nobility's power reduced. There were also parallel military reforms led by Gerhard von Scharnhorst, August Neidhardt von Gneisenau and Hermann von Boyen and educational reforms headed by Wilhelm von Humboldt. Gneisenau made it clear that all these reforms were part of a single programme when he stated that Prussia had to put its foundations in "the three-faced primacy of arms, knowledge and the constitution".[2]

It is harder to ascertain when the reforms ended – in the fields of the constitution and internal politics in particular, the year 1819 marked a turning point, with Restoration tendencies gaining the upper hand over constitutional ones. Though the reforms undoubtedly modernised Prussia, their successes were mixed, with results that were against the reformers' original wishes. The agricultural reforms freed some peasants, but the liberalisation of landholding condemned many of them to poverty. The nobility saw its privileges reduced but its overall position reinforced.

Reasons, aims and principles

Prussia in 1807

Prussia's position in Europe

In 1803, German Mediatisation profoundly changed the political and administrative map of Germany. Favourable to mid-ranking states and to Prussia, the reorganisation reinforced French influence. In 1805, the Third Coalition formed in the hope of stopping French domination of Europe from advancing further, but the coalition's armies were defeated at Austerlitz in December 1805. Triumphant, Napoleon I continued working towards dismantling the Holy Roman Empire. On 12 July 1806, he detached 16 German states from it to form the Confederation of the Rhine under French influence. On 6 August the same year, Francis I of Austria was forced to renounce his title of emperor, and the Empire had to be dissolved.

French influence reached as far as the Prussian frontier by the time Frederick William III of Prussia realised the situation. Encouraged by the United Kingdom, Prussia broke off its neutrality (in force since 1795) and repudiated the 1795 Peace of Basel, joined the Fourth Coalition and entered the war against France.[3] Prussia mobilised its troops on 9 August 1806 but two months later was defeated at Jena-Auerstedt. Prussia was on the verge of collapse, and three days after the defeat Frederick William III issued posters appealing to the inhabitants of his capital Berlin to remain calm.[4] Ten days later, Napoleon entered Berlin.

The war ended on 7 July 1807 with the first Treaty of Tilsit between Napoleon and Alexander I of Russia. Two days later, Napoleon signed a second Treaty of Tilsit with Prussia, removing half its territory[5] and forcing Prussia's king to recognise Jérôme Bonaparte as sovereign of the newly created Kingdom of Westphalia, to which Napoleon annexed the Prussian territories west of the river Elbe.[6] Prussia had had 9 million inhabitants in 1805,[7] of which it lost 4.55 million in the treaty.[8] It was also forced to pay 120 million francs to France in war indemnities[8] and fund a French occupying force of 150,000 troops.

Financial situation

The biting defeat of 1806 was not only the result of poor decisions and Napoleon's military genius, but also a reflection on Prussia's poor internal structures. In the 18th century the Prussian state had been the model of enlightened despotism for the rest of Germany. To the west and south, there was no single state or alliance that could challenge it. Yet in the era of Frederick II of Prussia it was a country oriented towards reform, beginning with the abolition of torture in 1740.

The economic reforms of the second half of the 18th century were based on a mercantilist logic. They had to allow Prussia a certain degree of self-sufficiency and give it sufficient surpluses for export. Joseph Rovan emphasises that

the state's interest required that its subjects were kept in good health, well nourished, and that agriculture and manufacture made the country independent of foreign countries, all the while allowing it to raise money by exporting surpluses[9]

Economic development also had to fund and support the military.[10] Prussia's infrastructure was developed in the form of canals, roads and factories. Roads connected its outlying regions to its centre, the Oder, Warta and Noteć marshes were reclaimed and farmed[11] and apple-growing was developed.

However, industry remained very limited, with heavy state-control. Trades were organised into monopolistic guilds and fiscal and customs laws were complex and inefficient. After the defeat of 1806, funding the occupation force and the war indemnities put Prussia's economy under pressure. As in the 18th century, the early 19th century reforms aimed to create budgetary margins, notably in their efforts towards economic development.

Administrative and legal situation

Frederick II of Prussia favoured both economic and political reform. His government worked on the first codification of Prussia's laws – the 19,000 paragraph General State Laws for the Prussian States. Article 22 indicated that all his subjects were equal before the law:

The state's laws unite all its members, without difference of status, rank or sex

.[12] However, Frederick died in 1786 leaving the code incomplete and was succeeded by Frederick William II of Prussia, who extended the same administrative structure and the same civil servants.

The absolutist system started to re-solidify under the obscurantist influence of Johann Christoph von Wöllner, financial privy councillor to Frederick William II. The reforms stalled, especially in the field of modernising society. The editing of the General State Laws was completed in 1792, but the French Revolution led to opposition to it, especially from the nobility.[13] It was then withdrawn from circulation for revision and did not come back into force until 1794. Its aims included linking the state and middle class society to the law and to civil rights, but at the same time it retained and confirmed the whole structure of the Ancien Régime.[11] Serfdom, for example, was abolished in Prussia's royal domains but not in the estates of the great landowners east of the river Elbe.[14] The nobility also held onto its position in the army and administration.

In 1797 Frederick William III succeeded his father Frederick William II, but at the time of his accession he found society dominated by the old guard, apart from the General State Laws promulgated in 1794. His own idea of the state was absolutist and he considered that the state had to be in the hands of the sovereign.[15] Before 1806, several observers and high-level civil servants such as Heinrich Friedrich Karl vom Stein and Karl August von Hardenberg underlined the fact that the Prussia state needed restructuring. As Minister of Finances and the Economy, Stein put some reforms in place, such as standardising the price of salt (then a state monopoly) and partially abolishing the export-import taxes between the kingdom's territories. In April 1806, he published Darstellung der fehlerhaften Organisation des Kabinetts und der Notwendigkeit der Bildung einer Ministerialkonferenz (literally Exposé on the imperfect organisation of the cabinet and on the necessity of forming a ministerial conference). In it, he wrote:

There should be a new and improved organisation of state affairs, to the measure of the state's needs born of circumstances. The main aim is to gain more strength and unity across the administration

.[16]

Start of the reforms

Trigger – the defeat of 1806

Prussia's war against Napoleon revealed the gaps in its state organisation. Pro-war and a strong critic of his sovereign's policies, Stein was dismissed in January 1807 after the defeat by France. However, Frederick William III saw that the Prussian state and Prussian society could only survive if they began to reform.[17] After the treaty of Tislsit, he recalled Stein as a minister on 10 July 1807 with the backing of Hardenberg and Napoleon, the latter of whom saw in Stein a supporter of France.[18] Queen Louise of Mecklenburg-Strelitz also supported Stein's re-appointment[19] – indeed, she was more in favour of reform than her husband and was its main initiator. Aided by Stein, Hardenberg and others, she had convinced her husband to mobilise in 1806 and in 1807 she had even met with Napoleon to demand that he review the hard conditions imposed in the treaty.[20] Hardenberg wrote the same year:

I believe that queen Louise could tell the king what the queen of Navarre, Catherine de Foix, said to her husband Jean d'Albret – "If we were born, your dear Catherine and my dear Jean, we would not have lost our kingdom"; for she would have listened to men of energy and asked advice, she would have taken them on and acted decisively. What [the king] lacks in personal strength is replaced in this way. An enterprising courage would have replaced a tolerant courage.[15]

Stein set certain conditions for his taking the job, among which was that the cabinets system should be abolished.[21] In its place, ministers had to win their right to power by speaking to the king directly. After this condition had been satisfied, Stein took up his role and was thus directly responsible for the civil administration as well as exercising a controlling role over the other areas. Frederick William III still showed little inclination to engage in reforms and hesitated for a long while.[22] The reformers thus had to expend much effort convincing the king. In this situation, it was within the bureaucracy and the army that the reformers had to fight the hardest against the nobility and the conservative and restorationist forces. The idealist philosophy of Immanuel Kant thus had a great influence on the reformers – Stein and Hardenberg each produced a treatise describing their ideas in 1807.

Nassauer Denkschrift

After his recall, Stein retired to his lands in Nassau. In 1807, he published the Nassauer Denkschrift, whose main argument was the reform of the administration.[23] In contrast to the reforms in the states of the Confederation of the Rhine, Stein's approach was traditionalist and above all anti-Enlightenment, focussing instead on critiquing absolutism. Stein followed English models such as the Glorious Revolution of 1688 and was sceptical of a centralised and militarised bureaucracy, favouring a decentralised and collegiate administration. With his collaborators, he followed (in his own words) a "policy of defensive modernisation, not with Napoleon but against him".[24]

According to Stein, the administration should be split up by field and no longer by geographical area.[25] Thus the administration had to be divided into two branches – the public revenue branch and the top-level state-policy branch (oberste Staatsbehörde). One of the main aims of this concept was to rationalise the state financial system to raise the money to meet its war indemnities under the treaty of Tilsit. Rationalising the state finances would allow the state to raise revenue but limit losses due to poor administrative organisation.

Stein was an anti-absolutist and an anti-statist, suspicious of bureaucracy and central government. For him, civil servants were only men paid to carry out their task with "indifference" and "fear of innovation".[26] Above all, he set out to decentralise and form a collegiate state.[27] Stein thus gave more autonomy to the provinces, Kreise and towns. Thanks to the different posts he had previously held, Stein, realised that he had to harmonise the government of the provinces.[26] He had recourse to the old corporative constitution, as he had experienced in Westphalia. The landowner, according to Stein, was the keystone to local self-government – "If the landowner is excluded from all participation in the provincial administration, then the link which links him to the fatherland remains unused".[26]

However, it was not only functional considerations which played a role for Stein. He felt he first had to educate the people in politics and provincial self-government was one of the most useful things in this area. On landowners' participation in the provincial administration, he wrote[28]

the economy as regards administrative costs is however the least important advantage gained by the landowners' participation in the provincial administration. What is much more important is to stimulate the spirit of the community and of the civic sense, the use of sleeping and poorly led forces and spreading knowledge, the harmony between the spirit of the nation, its views and its needs and those of the national administrations, the re-awakening of the feelings for the fatherland, independence and national honour.

In his reform projects, Stein tried to reform a political system without losing sight of the Prussian unity shaken by the defeat of 1806.

Rigaer Denkschrift

Stein and Hardenberg not only made a mark on later policy but also represented two different approaches to politics, with Hardenberg more steeped in Enlightenment ideas. He took the principles of the French Revolution and the suggestions created by Napoleon's practical policy on board more deeply than Stein.[29] Hardenberg was a statist who aspired to reinforce the state through a dense and centralised administration.[30] Nevertheless, these differences only represented a certain change of tendency among the reformers. The initiatives put in place were very much things of their own time, despite the latter umbrella concept of the 'Stein-Hardenberg reforms'.

The Rigaer Denkschrift was published the same year as Stein's work and presented on 12 September 1807. It bore the title 'On the reorganisation of the Prussian state'. Previously living in Riga, Hardenberg had been summoned in July by the king of Prussia under pressure from Napoleon.[31] Hardenberg developed ideas on the overall organisation of the Prussian state that were different from those of his fellow reformers. The main editors of the Rigaer Denkschrift were Barthold Georg Niebuhr, an expert financier, Karl vom Stein zum Altenstein, a future minister of Finances[32] and Heinrich Theodor von Schön. These three men concluded that the Revolution had given France a new impetus: "All the sleeping forces were re-awakened, the misery and weakness, the old prejudices and the shortcomings were destroyed."[33] Thus, in their view, Prussia had to follow France's example:

The folly of thinking that one can access the revolution in the safest way, remaining attached to the ancien regime and strictly following the principles for which it argues has only stimulated the revolution and made it continually grow larger. These principles' power is so great – they are so generally recognised and accepted, that the state that does not accept them must expect to be ruined or to be forced to accept them ; even the rapacity of Napoleon and his most-favoured aides are submitted to this power, and will remain so against their will. One cannot deny that, despite the iron despotism with which he governs, he nevertheless follows these principles widely in their essential features ; at least he is forced to make a show of obeying them.[34]

The authors thus favoured a revolution "im guten Sinn" or "in the right sense",[34] which historians later described as "revolution from above". Sovereigns and their ministers thus put in place reforms to gain all the advantages of a revolution without any of the disadvantages, such as losing their power or suffering from setbacks or outbreaks of violence.

As in Stein's Denkschrift, the Rigaer Denkschrift favours reviving national spirit to work with the nation and the administration. Hardenberg also sought to define society's three classes – the nobility, the middle class and the peasants. For him, the peasants took part in "the most numerous and most important but nevertheless the most neglected and belittled class in the state" and added that "the peasant class has to become the main object of our attention".[35] Hardenberg also sought to underline the principle of merit which he felt had to rule in society, by affirming "no task in the state, without exception, is for this or that class but is open to merit and to skill and to the ability of all classes".[36]

Overview of the reforms

Within fourteen months of his appointment, Stein put in place or prepared the most important reforms. The major financial crisis caused by the requirements of Tilsit forced Stein into a radical austerity policy, harnessing the state's machinery to raise the required indemnities. The success of the reforms begun by Stein was the result of a discussion already going on within the upper bureaucracy and Stein's role in putting them in place was variable – he was almost never, for example, involved in questions of detail. Many of the reforms were drafted by others among his collaborators, such as Heinrich Theodor von Schön in the case of the October decree.[37] However, Stein was responsible for presenting the reforms to the king and to other forces opposed to them, such as the nobility.

During Stein's short period of office, decisive laws were promulgated, even if the organizational law on state administration was not published until 1808 (i.e. after Stein's fall). It was during Stein's time in office that the edict of October 1807 and the cities' organizational reforms (Städteordnung) of 1808 were put into effect. After a short term of office by Karl vom Stein zum Altenstein, Hardenberg regained control of policy. From 1810, he bore the title of Staatskanzler,[38] retaining it until 1822. Thanks to him, land reform was completed via the Edicts of Regulation (Regulierungsedikten) of 1811 and 1816 as well as the Ablöseordnung (literally the redemption decree) of 1821. He also pushed through the reforms of trades such as the edict on professional tax of 2 November 1810 and the law on policing trades (Gewerbepolizeigesetz) of 1811. In 1818 he reformed the customs laws, abolishing internal taxes. As for social reform, the edict of emancipation was promulgated in 1812 for Jewish citizens. Despite the different initial situations and aims pursued, similar reforms were carried out in the states of the Confederation of the Rhine, except for the military and educational reforms. The Restoration tendencies put a stop to the reformist policy in Prussia around 1819 or 1820.[39][40]

Main reform fields

The reforms which were to be put in place were essentially a synthesis between historic and progressive concepts. Their aim was to replace the absolutist state structures which had become outdated. The state would have to offer its citizens the possibility of becoming involved in public affairs on the basis of personal freedom and equality before the law. The government's main policy aim was to make it possible to liberate Prussian territory from French occupation and return the kingdom to great-power status through modernising domestic policy.[41]

The Prussian subject had to become an active citizen of the state thanks to the introduction of self-government to the provinces, districts (kreise) and towns. National sentiment had to be awakened as Stein foresaw in his Nassau work,[28] but a citizen's duties were in some ways more important than his or her rights. Moreover, Stein's concept of self-government rested on a class-based society. A compromise between corporative aspects and a modern representative system was put in place. The old divisions into the three estates of nobility, clergy and bourgeoisie were replaced by divisions into nobility, bourgeoisie and peasants. The right to vote also had to be expanded, particularly to free peasants, which would be one of the bases for the freeing of the peasants in 1807.

The new organisation of power in the countryside and reform of industry were factors in the liberalisation of the Prussian economy.[42] In this respect, the Prussian reforms went much further than those in the states of the Confederation of the Rhine and were much more successful. The 1806 financial crisis, intensified by the indemnities, the occupation costs and other war costs, gave the necessary impetus for these changes – in all, Prussia had to pay France 120 million francs.[43] The freeing of the peasants, the industrial reforms and the other measures removed economic barriers and imposed free competition. The Prussian reforms relied on the economic liberalism of Adam Smith (as propounded by Heinrich Theodor von Schön and Christian Jakob Kraus) more heavily than the south German reformers. The Prussian reformers did not actively seek to encourage Prussian industry, which was then under-developed, but to remedy the crisis in the agricultural economy.[44][45]

State and administration

The reformers' top priority was to reorganise the administration and the state. Before 1806, there was not really a single Prussian state, but a multiplicity of states and provinces, mostly only held together by the single person of the king himself. There was no unified administration – instead there were the two parallel structures of decentralised administrations (each responsible for all portfolios within a single given territory) and a centralised administration (responsible for a single portfolio across the whole of Prussia). This double structure made any coordinated action difficult.[46] The government also had no overview of Prussia's economic situation and its government ministers had little clout faced with the king's cabinet, where they had less power than the king's private political councillors.

Bureaucracy and leadership

The start of the Stein era saw the unification of the Prussian state, with the old system of cabinets being abolished. A ministry of state (Staatsministerium) was introduced on 16 December 1808 in place of a top-level administration poorly defined as the Generaldirektorium. This reform was completed in 1810. Now the administration was ruled according to the principle of portfolios. The Staatsministerium included five major ministries – minister of the interior, minister for foreign affairs, minister for finances, minister for justice and minister of war, all responsible to the king alone.[47] These modifications could not take full effect, however, until a more effective statist model of leadership was created. This was done by replacing Prussian absolutism with a double domination of king and bureaucracy, in which the ministers had an important role, reducing the king's influence and meaning he could now only reign through his ministers' actions. In Stein's era, the Staatsministerium was organised in a collegiate way without a prime minister – that post was set up under Hardenberg, who received the title of Staatskanzler or State Chancellor in June 1810[38] along with control over the ministers' relations with the king.

The role of the head of state was also considerably modified. From 1808, Prussia was divided into districts. The different governments of these districts were set up according to the principle of portfolios, as with the national ministers of state. Each region was given an Oberpräsident for the first time, directly subordinate to the national ministers and with the role of stimulating public affairs.[48] Their rôle, which even went as far as putting up sanitary cordons in the event of an epidemic, was similar to that of French prefects – that is, to represent regional interests to the central government. The post was abolished in 1810 but revived in 1815 to play an important part in political life. It was in this context that justice and administration were separated once and for all.[49] On the establishment of administrative acts, the people concerned thus had a right of appeal. Nevertheless, there was no judicial control on the administration. Aiming to reduce any influence on the administration, this was reinforced by different administrative acts. The organisation that the reformers put in place served as a model for other German states and to major businesses.

National representation

In parallel to the Staatsministerium, Stein planned the creation of a Staatsrat or Privy Council.[50] However, he had had no opportunity to set up a correctly functioning one by 1808 and it was Hardenberg who set it up in 1810. The text of the relevant law stated:

We ordain a Council of State and by edict give our orders and our decisions on one side in this upper chamber and on the other side in our cabinet.[51]

The members of the Council of State had to be current ministers or former ministers, high-level civil servants, princes of the royal house or figures nominated by the king.[52] A commission was also formed to function as a kind of parliament, with major legislative rights. As a bastion of the bureaucracy, the Council of State had to prevent any return to absolutism or any moves to reinforce the interests of the Ancien Régime. The Council of State also had to subroge all laws and administrative and constitutional procedures.[53]

In the same way as the towns' self-government, Hardenberg foresaw the establishment of a national representative body made up of corporative and representative elements. The first assembly of notable figures was held in 1811 and the second in 1812. These were made up of a corporative base of 18 aristocratic landowners, 12 urban property owners and nine representatives from among the peasants. This corporative composition was based partly on the traditional conception of society and partly on practical and fiscal considerations[54] – in order to be able to pay its war indemnities to France, the Prussian state had to have massive recourse to credit contracts issued by the aristocrats and to gain credit in foreign countries the different states had to offer themselves as guarantors.

After the summoning of the provisional assemblies, it quickly became clear that their deputies' first priority was not the state's interests but more defending their own classes' interests. The nobility saw the reforms as trying to reduce their privileges and so blocked them in the assemblies, led by figures such as Friedrich August von der Marwitz and Friedrich Ludwig Karl Fink von Finkenstein. Their resistance went so far that the cabinet even resorted to imprisoning them at Spandau.[55] The historian Reinhart Koselleck has argued that the establishment of a corporative national representative body prevented all later reforms. At the end of the reforming period, the districts and the provincial representative bodies (such as the Provinziallandtage) remained based on corporative principles. Prussia was prevented from forming a true representative national body, with considerable consequences on the internal development of Prussia and the German Confederation. Thus, while the states of the Confederation of the Rhine located in southern Germany became constitutional states, Prussia remained without a parliament until 1848.[56][57]

Reform of the towns

Prior to the reforms the Prussian towns east of the river Elbe were under the state's direct control, with any surviving instances of self-government retaining their names and forms but none of their power. Stein's reform of the towns used this former tradition of self-government.[58] All rights specific to a certain city were abolished and all the cities put under the same structures and rule – this even came to be the case for their courts and police. Self-government was at the centre of the town reforms of 1808, with the towns now no longer subject to the state and their citizens given a duty to participate in the towns' political life.[59] This was the strongest indication of Stein's rejection of a centralised bureaucracy – self-government had to awaken its citizens' interest in public affairs in order to benefit the whole Prussian state.

The Städteordnung (Municipal Ordinance) of 1808 defined a citizen (or at least a citizen in the sense of the inhabitant of a town or city) as "a citizen or member of an urban community which possesses the right of citizenship in a town".[60] The municipal councillors were representatives of the town and not of an order or estate.[61] These councillors could be elected by all landowning citizens with a taxable revenue of at least 15 taler. A councillor's main task was to participate in the election of a municipal council or Magistrat, headed by a mayor. The election of the mayor and the members of the council had to be ratified by the central government. Different officials were put in place to carry out administrative portfolios. The council managed the municipal budget and the town also managed its own police.[62]

Despite some democratic elements, the town administrations retained large corporative elements – the groups were differentiated according to their estates and only citizens had full rights. Only landowners and industrial property-owners had a right to citizenship, though it was in principle also open to other people, such as Eximierten (bourgeois people, mostly those in state service) or Schutzverwandten (members of the lower classes without full citizenship rights). The costs linked to a citizen's octroi dissuaded many people. It was only the new reform of 1831 which replaced the 1808 assemblies of Bürger (citizens) with assemblies of inhabitants. Until the Vormärz, self-government in the towns was in the hands of artisans and established businessmen. In the cities and large towns, the citizens with full rights and their families represented around a third of the total population. Resistance by the nobility prevented these reforms from also being set up in the countryside.[56][63] These reforms were a step towards modern civic self-government.

Customs and tax reforms

Tax reform was a central problem for the reformers, notably due to the war indemnities imposed by Napoleon, and these difficulties marked Hardenberg's early reforms. He managed to avoid state bankruptcy[64] and inflation by increasing taxes or selling off lands.[65] These severe financial problems led to a wholesale fiscal reform. Taxes were standardised right across Prussia, principally by replacing the wide variety of minor taxes with main taxes. The reformers also tried to introduce equal taxation for all citizens, thus bringing them into conflict with aristocratic privileges. On 27 October 1810, the king proclaimed in his Finanzedikt:

We find we need to ask all our faithful subjects to pay increased taxes, mainly in the taxes on consumer goods and deluxe objects, though these will be simplified and charged on fewer articles, associated with the raising of complementary taxes and excises all as heavier taxes. These taxes will be borne in a proportional manner by all the classes of the nation and will be reduced as soon as the unfortunate need disappears.[Note 1]

Excises were raised the following year on appeals.[67]

In 1819, excise (originally only raised by the towns) was suppressed and replaced with a tax on the consumption of beer, wine, gin and tobacco.[68] In the industrial sphere, several taxes were replaced with a progressively spread-out professional tax. Other innovations were an income tax and a tax on wealth based on a tax evaluation carried out by the taxpayer. 1820 saw protests against a tax on classes, the tax being defined by the taxpayer's position in society.[68] This tax on classes was an intermediate form between poll tax and income tax. The towns had the possibility of retaining the tax on cattle and cereal crops. The results for fiscal policy remain controversial. The nobility was not affected by the taxes as the reformers had originally planned, so much so that they did not managed to put in place a 'foncier' tax also including the nobility. The poorest suffered most as a result of these measures.[69]

It was only after the end of the Napoleonic Wars and after the territorial reorganisation of Europe at the Congress of Vienna that Prussia's customs duties were reformed. At the Congress Prussia regained its western territories, leading to economic competition between the industrialised part of these territories such as the Rhine Province, the Province of Westphalia and the territories in Saxony on the one hand and the essentially agricultural territories to the east of the Elbe on the other. Customs policy was also very disparate.[67] Thus, in 1817, there were 57 customs tariffs on 3,000 goods passing from the historic western territories to the Prussian heartland, with the taxes in the heartland not yet having spread to the formerly French-dominated western provinces.

This was one of the factors that made customs reform vital. That reform occurred on 26 May 1818, with the establishment of a compromise between the interest of the major landowners practicing free-exchange and those of the still-weak industrial economy asking for protectionist custom duties. They therefore only took on what would now be called a tax for protecting internal markets from foreign competition and customs duties for haulage were lifted.[70] The mercantile policy instituted by Frederick II thus came to an end. Export bans were lifted.[71] The customs laws and duties put in place by the reformers proved so simple and effective over time that they served as a model for taxation in other German states for around fifty years and that their basic principles remained in place under the German Empire. The Prussian customs policy was one of the important factors in the creation of the Deutscher Zollverein in the 1830s.[72][73]

Society and politics

Agricultural reforms

Agriculture was reformed across Europe at this time, though in different ways and in different phases. The usefulness of existing agricultural methods came into doubt and so the Ancien Régime's and Holy Roman Empire's agricultural structures were abolished. Peasants were freed and became landowners; and services and corvées were abolished. Private landownership also led to the breakdown of common lands – that is, to the usage of woods and meadows 'in common'. These communal lands were mostly given to lords in return for lands acquired by the peasants. Some meadow reforms had already taken place in some parts of Prussia before 1806, such as the freeing of the peasants on royal lands in the 18th century, though this freeing only fully came into force in 1807.

The landowning nobility successfully managed to oppose similar changes. The government had to confront aristocratic resistance even to the pre-1806 reforms, which became considerable. The Gesindeordnung of 1810 was certainly notable progress for servants compared to that proposed in the General State Laws, but still remained conservative and favourable to the nobility. The nobility's opposition to this also led to several privileges being saved from abolition. The rights of the police and the courts were controlled more strongly by the state, but not totally abolished like religious and scholarly patrongage, hunting rights and fiscal privileges. Unlike the reforms in the Kingdom of Bavaria, the nobles were not asked to justify their rank. The reformers made compromises, but the nobility were unable to block the major changes brought by the reforms' central points.[74][75]

Edict of October 1807

The freeing of the peasants marked the start of the Prussian reforms. The kingdom's modernisation began by modernising its base, that is, its peasants and its agriculture. At the start of the 19th century, 80% of the German population lived in the countryside.[76] The edict of 9 October 1807, one of the central reforms, liberated the peasants and was signed only five days after Stein's appointment on von Schön's suggestion. The October edict began the process of abolishing serfdom and its hereditary character. The first peasants to be freed were those working on the domains in the Reichsritter and on 11 November 1810 at the latest, all the Prussian serfs were declared free:[77]

On St Martin's Day 1810 all servitude ended throughout our states. After St Martin's Day 1810, there would be nothing but free people as was already the case over our domains in our provinces[...].[Note 2]

However, though serfdom was abolished, corvées were not – the October edict said nothing on corvées.[79] The October edict authorised all Prussian citizens to acquire property and choose their profession, including the nobles, who until then could not take on jobs reserved for the bourgeoisie:

Any nobleman is authorised, without prejudice to its estate, to take up a bourgeois job ; and any bourgeois or peasant is authorised to join the bourgeoisie in the case of the peasant or the peasantry in the case of the bourgeois.[Note 3]

The principle of "dérogeance" disappeared.

The peasants were allowed to travel freely and set up home in the towns and no longer had to buy their freedom or pay for its with domestic service. The peasants no longer had to ask their lord's permission to marry – this freedom in marriage led to a rising birth rate and population in the countryside. The freeing of the peasants, however, was also to their disadvantage – lordly domains were liberalised and major landowners were allowed to buy peasants' farms (the latter practice having been illegal previously). The lords no longer had an obligation to provide housing for any of their former serfs who became invalids or too old to work. This all led to the formation of an economic class made up of bourgeois and noble entrepreneurs who opposed the bourgeoisie.[80]

Edict of regulation (1811)

After the reformers freed the peasants, they were faced with other problems, such as the abolition of corvées and the establishment of properties. According to the General State Laws, these problems could only be solved by compensating the financiers. The need to legally put in place a "revolution from above" slowed down the reforms.

The edict of regulation of 1811 solved the problem by making all peasants the owners of the farms they farmed. In place of buying back these lands (which was financially impossible), the peasants were obliged to compensate their former lords by handing over between a third and a half of the farmed lands.[81] To avoid splitting up the lands and leaving areas that were too small to viably farm, in 1816 the buy-back of these lands was limited to major landowners. The smaller ones remained excluded from allodial title.[82] Other duties linked to serfdom, such as that to provide domestic service and the payment of authorisation taxes on getting married, were abolished without compensation. As for corvées and services in kind, the peasants had to buy back from their lords for 25% of their value.

The practical compensations in Prussia were without doubt advantageous compared to the reforms put in place in the states of the Confederation of the Rhine. In effect, they allowed the process of reform to be accelerated. Nevertheless, the 12,000 lordly estates in Prussia saw their area increase to reach around 1.5 million Morgen[83] (around 38,000 hectares), mostly made up of common lands, of which only 14% returned to the peasants, with the rest going to the lords. Many of the minor peasants thus lost their means of subsistence and most could only sell their indebted lands to their lords and become agricultural workers.[84] Some jachère lands were made farmable, but their cultivation remained questionable due to their poor soil quality. The measures put in place by the reformers did have some financial success, however, with Prussia's cultivated land rising from 7.3 to 12.46 million hectares in 1848[84] and production raised by 40%.[82]

In the territories east of the Elbe, the agricultural reforms had major social consequences. Due to the growth of lordly estates,[83] the number of lordly families rose greatly, right up until the second half of the 19th century. The number of exploited lands remained the same. A very important lower social class was also created. According to region and the rights in force, the number of agricultural day workers and servants rose 2.5 times. The number of minor landowners, known as Kätner after their homes (known as Kotten), tripled or even quadrupled. Many of them were dependent on another job. Ernst Rudolf Huber, professor of public law, judged that the agricultural reforms were

one of the tragic ironies of German constitutional history. Through it was shown the internal contradiction of the bourgeois liberalism which created the liberty of the individual and his property and at the same time – due to its own law of the liberty of property – unleashed the accumulation of power in the hands of some people.[85]

Reform of industry and its results

The reformers aspired to free individual forces in the industrial sphere just as in the agricultural one, in their devotion to the theories of Adam Smith. To free these forces, they had to get rid of guilds and an economic policy based on mercantilism. To encourage free competition also meant the suppression of all limitations on competition.

It was in this context that the freedom of industry (Gewerbefreiheit) was introduced in 1810–1811.[86] To set up an industry, one had to acquire a licence, but even so there were exceptions, such as doctors, pharmacists and hotelliers. The guilds lost their monopoly role and their economic privileges. They were not abolished, but membership of them was now voluntary, not compulsory as it had been in the past. State control over the economy also disappeared, to give way to a free choice of profession and free competition. The reform of industry unlocked the economy and gave it a new impetus. There was no longer any legal difference in the industrial sphere between the town and the countryside. Only mining remained as an exception until the 1860s.

Originally planned to encourage rural industry, the freedom of industry became the central condition for Prussian economic renewal on an industrial base. As had happened with the nobility, the citizens of the towns arose unsuccessfully opposed the reforms. Their immediate results were contradictory—early on, non-guild competition was weak, but after a period of adaptation the number of non-guild artisans rose significantly. However, in the countryside, the burdens of the artisans and other industries rose considerably. This rise in the number of artisans was not accompanied by a similar growth in the rest of the population.[85] The number of master-craftsmen rose too, but master-craftsmen remained poor due to the strong competition. During the Vormärz, tailors, cobblers, carpenters and weavers were the main over-subscribed trades. The rise in the lower classes in the countryside accentuated the 'social question and would be one of the causes of the 1848 Revolution.[85][87][88]

Jewish emancipation

By the Edict of Emancipation of 11 March 1812, Jews gained the same rights and duties as other citizens:

We, Frederick William, King of Prussia by the Grace of God, etc. etc., having decided to establish a new constitution conforming to the public good of Jewish believers living in our Kingdom, proclaim all the former laws and prescriptions not confirmed in this present Edict to be abrogated.[89]

To gain civil rights, all Jews had to declare themselves to the police within six months of the promulgation of the edict and choose a definitive name.[90] This Edict was the result of a long reflection since 1781, begun by Christian Wilhelm von Dohm, pursued by David Friedländer in a thesis to Frederick William II in 1787 (Friedländer approved the Edict of 1812[91]). Humboldt's influence allowed for the so-called "Jewish question" to be re-examined.[92]

Article 8 of the Edict allowed Jews to own land and take up municipal and university posts.[93] The Jews were free to practise their religion and their traditions were protected. Nevertheless, unlike the reforms in the Kingdom of Westphalia, the Edict of Emancipation in Prussia did have some limitations – Jews could not become army officers or have any government or legal role, but were still required to do military service.

Even if some traditionalists opposed the Edict of Emancipation,[94] it proved a major step towards Jewish emancipation in the German states during the 19th century. The judicial situation in Prussia was significantly better than that in most of southern and eastern Germany, making it an attractive destination for Jewish immigration.[95]

Other areas

Education

New organisation

For the reformers, the reform of the Prussian education system (Bildung) was a key reform. All the other reforms relied on creating a new type of citizen who had to be capable of proving themselves responsible and the reformers were convinced that the nation had to be educated and made to grow up. Unlike the state reforms, which still contained corporative elements, the Bildungsreform was conceived outside all class structures. Wilhelm von Humboldt was the main figure behind the educational reform. From 1808, he was in charge of the department of religion and education within the ministry of the interior. Like Stein, Humboldt was only in his post for a short time, but was able to put in place the main elements of his reforms.

Humboldt developed his ideas in July 1809 in his treatise Über die mit dem Königsberger Schulwesen vorzunehmende Reformen (On reforms to execute with the teaching in Königsberg). In place of a wide variety of religious, private, municipal and corporative educational institutions, he suggested setting up a school system divided into Volksschule (people's schools), Gymnasiums and universities. Humboldt defined the characteristics of each stage in education. Elementary teaching "truly only need be occupied with language, numbers and measures, and remain linked to the mother tongue being given that nature is indifferent in its design".[Note 4] For the second stage, that of being taught in school, Humboldt wrote "The aim of being taught in school is to exercise [a pupil's] ability and to acquire knowledge without which scientific understanding and ability are impossible.[Note 5] Finally, he stated that university had to train a student in research and allow him to understanding "the unity of science".[97] From 1812, a university entry had to obtain the Abitur. The state controlled all the schools, but even so it strictly imposed compulsory education and controlled exams. To enter the civil service, performance criteria were set up. Education and performance replaced social origin.

New humanism

Wilhelm von Humboldt backed a new humanism.[98] Unlike the utilitarian teaching of the Enlightenment, which wished to transmit useful knowledge for practical life, Humboldt desired a general formation of man. From then students had to study antiquity and ancient languages to develop themselves intellectually.[99] Not only would they acquire this humanistic knowledge, they would also acquire other knowledge necessary for other jobs. The state would not seek to form citizens at all costs to serve it, but it did not entirely let go of that aim:

Each [student] who does not give evidence of becoming a good artisan, businessman, soldier, politician is still a man and a good citizen, honest, clear according to his rank without taking account of his own job. Give him the necessary training and he will acquire the particular capacity for his job very easily and always hold onto liberty, as is the case so often in life, going from one to the other.[Note 6]

Unlike Humboldt, for whom the individual was at the centre of the educational process, the republican Johann Gottlieb Fichte rather leaned towards national education to educate the whole people and thus to affirm the nation in the face of Napoleonic domination.[101]

In paying professors better and improving their training, the quality of teaching in the Volksschules was improved. The newly founded gymnasia offered a humanist education to ready pupils for university studies. In parallel Realschules were set up[102] to train men in manual trades. Some schools for officer cadets were allowed to remain. Despite stricter state influence and control, the religious authorities retained their role in inspecting schools.

Universities

In Humboldt's thinking, university represented the crowning glory of intellectual education and the expression of the ideal of freedom between teaching and research held an important place in it. German universities of the time were mostly mediocre.[103] For Humboldt, "the state must treat its universities neither as gymnasia nor as specialist schools and must not serve its Academy as a technical or scientific deputation. Together, they must [...] demand nothing of them which does not give it profit immediately and simply".[Note 7]

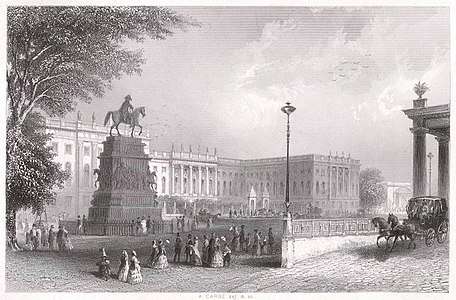

Students, in his view, had to learn to think autonomously and work in a scientific way by taking part in research. The foundation of Berlin University served as a model. It was opened in 1810 and the great men of the era taught there – Johann Gottlieb Fichte, the physician Christoph Wilhelm Hufeland, the historian Barthold Georg Niebuhr and the jurist Friedrich Carl von Savigny.[105]

In practice, the educational reforms' results were different from what Humboldt had expected. Putting in place his ideal of philological education excluded the lower classes of society and allied the educational system to the restorationist tendencies. The major cost of education rendered the reforms in this area ineffective. The reformers had hoped that people would rise through the social scale thanks to education, but this did not happen so well as they had hoped.[106]

Military

Unlike the reforms in the states of the Confederation of the Rhine, the Prussian policy was aimed against French supremacy right from the start. Also, the Prussian military reforms were much more profound than those in the south German states. They were instigated by a group of officers which had formed after the defeats of 1806 and notably included Scharnhorst, Gneisenau, Boyen, Grolman and Clausewitz.[68]

Chief of staff since 1806, Scharnhorst became head of the military reorganisation commission set up by Frederick William III in July 1807. For him, every citizen was a born defender of the state.[107] His main aim was to drive out the French occupiers. In close contact with Stein, Scharnhorst managed to convince the king that the military needed reform. Like the civil administration, the military organisation was simplified, via the creation of a Prussian ministry of war and of an army staff on 25 December 1808.[108] Scharnhorst was at the head of the new ministry and he aimed his reforms at removing the obstacles between army and society and at making the army ground itself in the citizens' patriotism.

Military service

The experiences of 1806 showed that the old organisation of the Prussian army was no longer a match for the might of the French army. Compared to the French defensive tactics, Prussian tactics were too immobile. Its officers treated their soldiers as objects and punished them severely[41] – one of the most severe punishments, the Spießrutenlaufen, consisted of making a soldier pass between two ranks of men and be beaten by them. The French instead had compulsory military service and the Prussian army's adoption of it was the centre of Prussia's military reforms.

Frederick William III hesitated about the military reforms, the officer corps and nobility resisted them and even the bourgeoisie remained sceptical. The start of the German campaign of 1813 was the key factor. On 9 February 1813 a decree replaced the previous conscription system with an obligation to serve by canton (Kantonpflichtigkeit),[109] and this new system had to last for the whole war. Thus it looked to restore the pride and position of the common soldier in adapting army discipline to civil law. The punishments and in particular the 'schlague' (consisting of a soldier being beaten) were abolished. The social differences had to disappear. The Treaty of Tilsit had reduced the Prussian army to 42,000 men, but Scharnhorst put in place the "Krümper system",[110] which consisted of training a number of soldiers in rotation without ever exceeding the numbers authorised by the Treaty. Between 30,000 and 150,000 supplementary men were also trained – the training system changed several times and so it is difficult to work out precise numbers.[111] Compulsory military service was ordered by Frederick William III on 27 May 1814 then fixed by a military law on 3 September the same year:

Every man of 20 years is obliged to defend the fatherland. To execute this general obligation, particularly in time of peace, in such manner that the progress of science and industry will not be disturbed, the following exclusion must be applied in taking into account the terms of service and the duration of service.[112]

Other

The officer corps was also reformed and the majority of officers dismissed.[113] The nobility's privilege was abolished and a career as an officer was opened up to the bourgeois. The aristocrats disliked this and protested, as with Ludwig Yorck von Wartenburg. In practice a system of co-opting of officers was put in place which generally favoured the nobility, even if there remained some (albeit minor) bourgeois influence. Starting with the regiment of chasseurs on campaign, chasseur and protection units were set up.[114] It was Yorck von Wartenburg who from June 1808 occupied on their training.[115] In the officer corps, it was now the terms of service not the number of years served which determined promotion. The Prussian Academy of War also provided better officer training than before – dissolved after the defeat at Jena, it had been refounded in 1810 by Scharnhorst.[116]

Starting in 1813–1814[117] with the line infantry troops, we also see the Landwehr,[118] which served as reserve troops to defend Prussia itself. It was independent in organisation and had its own units and its own officers. In the Kreise (districts), commissions organised troops in which the bourgeois could become officers. The reformers' idea of unifying the people and the army seems to have succeeded.[119] Volunteer chasseur detachments (freiwillige Jägerdetachements) were also formed as reinforcements.[120]

Main leaders

The reforms are sometimes named after their leaders Stein and Hardenberg, but they were also the fruit of a collaboration between experts, each with his own speciality. One of these experts was Heinrich Theodor von Schön – born in 1773, he had studied law at Königsberg university to follow a career in political sciences. In 1793 he entered Prussian service.[121] Nine years later, he became financial councillor to the Generaldirektorium. When the Prussian government fled to Königsberg after its defeat at Jena, he followed Stein there. It was there that he brought to bear his expertise on serfdom and it was his treatise that would help Stein write the October edict. Unlike Stein, Schön backed a greater liberalisation of landowning – for him, economic profitability had to take first priority, even if this was to the peasants' disadvantage.[122] From 1816, Schön became Oberpräsident, a post he held for around 40 years,[123] and devoted himself to the economic and social life of the provinces which he governed.[122]

Schön also took part in editing the Rigaer Denkschrift. In 1806 he travelled with a group of civil servants that had gathered around the just-dismissed Hardenberg – the group also included Karl vom Stein zum Altenstein, Friedrich August von Stägemann and Barthold Georg Niebuhr.[124] Niebuhr had studied law, philosophy and history at the university of Kiel between 1794 and 1796. In 1804 he was made head of the Danish national bank. His reputation as a financial expert quickly spread to Prussia. On 19 June 1806, Niebuhr and his family left for Riga with other civil servants to work with Hardenberg when he was dismissed. On 11 December 1809, he was made financial councillor and section chief for state debt. In 1810, he edited a note to the king in which he expressed strong doubts on whether a financial plan put in place by Hardenberg could be realised. Its tone he employed was so strong that the king disavowed him[125] and so Niebuhr retired from politics.

The three other civil servants present at Riga – Karl vom Stein zum Altenstein, Wilhelm Anton von Klewitz and Friedrich August von Stägemann – also played important rôles in the reforms. Altenstein became high financial councillor in the Generaldirektorium. When Stein was dismissed in 1807, Altenstein and the minister of finances Friedrich Ferdinand Alexander zu Dohna-Schlobitten put in place the state reform conceived by Stein.[126] In 1810, Klewitz and Theodor von Schön edited the Verordnung über die veränderte Staatsverfassung aller obersten Staatsbehörden (Decree on the new constitution of all the high portfolios of state). Other collaborators took part in the reforms, such as Johann Gottfried Frey (chief of police in Königsberg and the real author of the Städteordnung[127]), Friedrich Leopold Reichsfreiherr von Schrötter (who collaborated with Stein on the Städteordnung), Christian Peter Wilhelm Beuth (in Prussian service since 1801, who had collaborated with Hardenberg on the fiscal and industrial laws) and Christian Friedrich Scharnweber (who had some influence on Hardenberg[128]).

Resurgence of Prussia

From 1806 onwards isolated uprisings occurred in Germany and the German-speaking countries. On 26 August 1806 the bookseller Johann Philipp Palm was shot for publishing an anti-Napoleon pamphlet,[129] to a strong public outcry. In 1809, Andreas Hofer launched an insurrection in the Tyrol, but met the same fate as Palm. Anti-Napoleonic feeling developed little by little, with Germans feeling their spirits weighed down by the French occupation and Prussia still paying huge indemnities to the French. When Napoleon's 1812 invasion of Russia met with disaster, it lit a glimmer of hope in Germany and above all in Prussia. On 30 December 1812, Yorck von Wartenburg signed the convention of Tauroggen,[130] by which Prussia in effect turned against Napoleon and repudiated the Treaty of Tilsit.

On 13 March 1813 Frederick William III made his 'An Mein Volk' speech, making an appeal:

To my people! ... Brandenburgers, Prussians, Silesians, Pomeranians, Lithuanians! You know what you have endured for nearly seven years, you know what will be your sad fate if we do not end with honour the fight we have begun. Remember past times, the Great Elector, the great Frederick [II]. Keep in your minds the good things our ancestors won under his command: freedom of conscience, honour, independence, trade, industry and science. Keep in your minds the great example of our powerful Russian allies, keep in your mind the Spanish, the Portuguese, even the lesser people who have declared war on powerful enemies to win the same good things and have gained victory [...] Great sacrifices are demanded of all classes, for our beginning is great and the numbers and resources of our enemies are great [...] But whatever the sacrifices demanded of the individual, they pale beside the holy goods for which we make them, for the things for which we fight and must win if we do not wish to stop being Prussians and Germans.[131]

The following 27 March Prussia declared war on France and the following 16–19 October saw the beginning of the end for Napoleonic power with the battle of Leipzig. On 1 October 1815 the Congress of Vienna opened and at it Harbenberg represented the victorious Kingdom of Prussia.

Historiography

Early analyses

In late 19th century historiography, the Prussian reforms and the "revolution from above" were considered by Heinrich von Treitschke and others to be the first step in the foundation of the German Empire on the basis of a 'small-Germany' solution. For Friedrich Meinecke, the reforms put in place the conditions necessary for the future evolution of Prussia and Germany. For a long time, under the influence of Leopold von Ranke, the era of reforms was presented first and foremost as a story of the deeds and destinies of "great men", as shown by the large number of biographies written about the reformers – Hans Delbrück wrote about Gneisenau and Meinecke about Boyen, for example.

Indeed, it was the military reforms which first gained the researchers' interest. It was only with the biography of Max Lehmann that Stein's life and actions were analysed. Unlike Stein, the biographers paid little attention to Hardenberg. Despite the significant differences between Stein and Hardenberg, historiography saw a fundamental continuity between their approaches that made them one single unified policy.[132]

Some authors, such as Otto Hintze, underlined the role of reform programmes such as the General State Laws of 1794. One such continuity confirmed the theory that the reformers were already a distinct group before the reforms occurred. Thomas Nipperdey resumed the debate by writing that there had been reform plans before the disaster of 1806, but that those behind them had lacked the energy to put them into force and also lacked internal cohesion.[14] As for the agricultural reforms, the works of Georg Friedrich Knapp aroused a controversy at the end of the 19th century – he criticised the reform policy, stating that it favoured the aristocrats' interests and not the peasants' interests. He held Adam Smith's liberal interest responsible for the evolution of certain problems. Research later led to a global critique which could not be maintained. After all, the peasants' properties were developed, even if the lands they gained were most often revealed to be poor soil.[133]

Nuances in criticism

Today, the industrial reforms' success is also critiqued in a more nuanced way. They are considered not to have been the immediate reason for the artisans' misery, instead taken as the reduced influence of the legislation on their development. The historian Barbara Vogel tried to address an overall concept of agricultural and industrial approaches and to describe them as a "bureaucratic strategy of modernisation".[134] When industrial development was taken into account, the policy of reforms is seen to certainly be centred on the encouragement of rural industry in the historic Prussian territories, thus allowing the onset of Prussia's industrial revolution.

Reinhart Koselleck tried to give a general interpretation of the reform policy in view of the 1848 revolution, in his work Preußen zwischen Reform und Revolution (Prussia between Reform and Revolution). He distinguished three different processes. The General State Laws represented – at the time of its publication – a reaction to social problems, but remained attached to corporative elements. Koselleck saw the birth of an administrative state during the reform era and during the reinforcement of the administration between 1815 and 1825 as an anticipation of the later constitution. However, in his view, the following decades saw the political and social movement suppressed by the bureaucracy. After the end of the reform period, Koselleck underlined that there was a rupture in the equilibrium between the high level civil servants and the bourgeois of the 'Bildungsbürgertum' who could not become civil servants. According to him, the bureaucracy represented the general interest against the individual interest and no national representative body was set up for fear of seeing the reforming movement stopped.[135]

The historian Hans Rosenberg and later the representatives of the Bielefeld School supported the theory that the end of the process which would have led to a constitution in Prussia was one of the reasons for the end to its democratisation and for the Sonderweg. Hans-Jürgen Puhle, professor at Frankfurt University, even held the Prussian regime to be "in the long term programmed for its own destruction".[136] Other writers more orientated towards historicism such as Thomas Nipperdey underlined the divergence between the reformers' intentions and the unexpected later results of the reforms.

Several decades ago, the Prussian reforms from 1807 to 1819 lost their central position in historical study of 19th-century Germany. One contributing factor to this decline is that the reforms in the states of the Confederation of the Rhine were considered as similar by several historians. Another is that the Prussian regions – dynamic in industry and society – belonged to the French sphere of influence directly or indirectly until the end of the Napoleonic era.[137]

Memorials to the reformers

Statues

Several statues of the reformers were set up, especially of Stein. In 1870 a statue of Stein by Hermann Schievelbein was put up on the Dönhoffplatz in Berlin. Around its base can be read "To minister Baron vom Stein. The recognition of the fatherland.".[138] A statue of Hardenberg by Martin Götze was also put up beside it in 1907. Stein's statue now stands in front of the Landtag of Prussia in Berlin.

Cologne memorial

One of the most important monuments to the reformers is that in the Heumarkt in Cologne, made up of an equestrian statue of Frederick William III by Gustav Blaeser on a base surrounded by statues of important figures of the era, including several Prussian reformers: Stein, Hardenberg, Gneisenau, Scharnhorst, Humboldt, Schön, Niebuhr and Beuth. The monument's design process had been launched in 1857[139] and it was inaugurated on 26 September 1878, with a medal marking the occasion bearing William I of Germany and his wife on the obverse and the monument and the phrase "To king Frederick William III, the Rhine states recognise him" on the reverse. The monument recalled the Berlin equestrian statue of Frederick the Great, designed by Christian Daniel Rauch, master of Blaeser.

Other

Stein featured on commemorative stamps in 1957 and 2007 and Humboldt in 1952, whilst several streets are now named after the reformers, especially in Berlin, which has a Humboldtstraße, a Hardenbergstraße, a Freiherr-vom-Stein-Straße, a Niebuhrstraße, a Gneisenaustraße and a Scharnhorststraße.

Further reading

History of Prussia

- (in French) Jean Paul Bled, Histoire de la Prusse (History of Prussia), Fayard, 2007 ISBN 2-213-62678-2

- (in German) Otto Büsch/Wolfgang Neugebauer (Bearb. u. Hg.): Moderne Preußische Geschichte 1648–1947. Eine Anthologie, 3 volumes, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin, New York, 1981 ISBN 3-11-008324-8

- (in German) Wolfgang Neugebauer, Die Geschichte Preußens. Von den Anfängen bis 1947, Piper, Munich, 2006 ISBN 3-492-24355-X

- (in German) Thomas Nipperdey, Deutsche Geschichte 1800–1866. Bürgerwelt und starker Staat, Munich, 1998 ISBN 3-406-44038-X

- (in German) Eberhard Straub, Eine kleine Geschichte Preußens, Siedler, Berlin, 2001, ISBN 3-88680-723-1

Reforms

- Christopher Clark, Iron Kingdom – The Rise and Downfall of Prussia, 1600–1947, London, 2006, chapters 9 to 12, pp. 284 to 435

- Marion W. Gray, Prussia in Transition. Society and politics under the Stein Reform Ministry of 1808, Philadelphia, 1986

- (in French) René Bouvier, Le redressement de la Prusse après Iéna, Sorlot, 1941

- (in French) Godefroy Cavaignac, La Formation de la Prusse contemporaine (1806–1813). 1. Les Origines – Le Ministère de Stein, 1806–1808, Paris, 1891

- (in German) Gordon A. Craig, Das Scheitern der Reform: Stein und Marwitz. In: Das Ende Preußens. Acht Porträts. 2. Auflage. Beck, München 2001, pp. 13–38 ISBN 3-406-45964-1

- (in German) Walther Hubatsch, Die Stein-Hardenbergschen Reformen. Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, 1989 ISBN 3-534-05357-5

- (in German) Paul Nolte, Staatsbildung und Gesellschaftsreform. Politische Reformen in Preußen und den süddeutschen Staaten 1800–1820, Frankfurt/New York, Campus-Verlag, 1990 ISBN 3-593-34292-8

- (in French) Maurice Poizat, Les Réformes de Stein et de Hardenberg et la Féodalité en Prusse au commencement du XIXe siecle, thèse pour le doctorat, Faculté de Droit, Paris, 1901

- (in German) Barbara Vogel, Preußische Reformen 1807–1820, Königstein, 1980

Aspects of the reforms

- (in German) Christof Dipper, Die Bauernbefreiung in Deutschland 1790–1850, Stuttgart, 1980

- (in German) Georg Friedrich Knapp, Die Bauernbefreiung und der Ursprung der Landarbeiter in den älteren Teilen Preußens T. 1: Überblick der Entwicklung, Leipzig, 1887

- (in German) Clemens Menze, Die Bildungsreform Wilhelm von Humboldts, Hannover, 1975

- (in German) Wilhelm Ribhegge, Preussen im Westen. Kampf um den Parlamentarismus in Rheinland und Westfalen. Münster, 2008

- (in German) Hans-Ulrich Wehler, Deutsche Gesellschaftsgeschichte. Erster Band: Vom Feudalismus des alten Reiches bis zur defensiven Modernisierung der Reformära. 1700–1815. München: C.H. Beck, 1987 ISBN 3-406-32261-1

- (in German) Theodor Winkler/Hans Rothfels, Johann Gottfried Frey und die Enstehung der preussischen Selbstverwaltung, Kohlhammer Verlag, 1957

Notes

- "Wir sehen Uns genöthigt, von Unsern getreuen Unterthanen die Entrichtung erhöhter Abgaben, hauptsächlich von der Konsumtion und von Gegenständen des Luxus zu fordern, die aber vereinfacht, auf weniger Artikel zurückgebracht, mit Abstellung der Nachschüsse und der Thoraccisen, so wie mehrerer einzelner lästigen Abgaben, verknüpft und von allen Klassen der Nation verhältnißmäßig gleich getragen, und gemindert werden sollen, sobald das damit zu bestreitende Bedürfniß aufhören wird."[66]

- "Mit dem Martini-Tage Eintausend Achthundert und Zehn (1810.) hört alle Guts-Unterthänigkeit in Unsern sämmtlichen Staaten auf. Nach dem Martini-Tage 1810. giebt es nur freie Leute, so wie solches auf den Domainen in allen Unsern Provinzen schon der Fall ist [...]"[78]

- "Jeder Edelmann ist, ohne allen Nachtheil seines Standes, befugt, bürgerliche Gewerbe zu treiben; und jeder Bürger oder Bauer ist berechtigt, aus dem Bauer- in den Bürger und aus dem Bürger- in den Bauerstand zu treten"[25]

- "Er hat es also eigentlich nur mit Sprach-, Zahl- und Mass-Verhältnissen zu thun, und bleibt, da ihm die Art des Bezeichneten gleichgültig ist, bei der Muttersprache stehen."[96]

- "Der Zweck des Schulunterrichts ist die Uebung der Fähigkeit, und die Erwerbung der Kenntnisse, ohne welche wissenschaftliche Einsicht und Kunstfertigkeit unmöglich ist."[96]

- "Jeder ist offenbar nur dann ein guter Handwerker, Kaufmann, Soldat und Geschäftsmann, wenn er an sich und ohne Hinsicht auf seinen besonderen Beruf ein guter, anständiger, seinem Stande nach aufgeklärter Mensch und Bürger ist. Gibt ihm der Schulunterricht, was hierzu erforderlich ist, so erwirbt er die besondere Fähigkeit seines Berufs nachher sehr leicht und behält immer die Freiheit, wie im Leben so oft geschieht, von einem zum anderen überzugehen"[100]

- "Der Staat muss seine Universittendäten weder als Gymnasien noch als Specialschulen behandeln, und sich seiner Akademie nicht als technischen oder wissenschaftlichen Deputation bedienen. Er muss im Ganzen [...] von ihnen nichts fordern, was sich unmittelbar und geradezu auf ihn bezieht."[104]

References

- Dwyer 2014, p. 255.

- Cited after Nipperdey (1998), p. 51

- Rovan (1999), p. 438

- Nordbruch (1996), p. 187

- Knopper & Mondot (2008), p. 90

- Demel & Puschner (1995), p. 53

- Pölitz (1830), p. 95

- Büsch (1992), p. 501

- Rovan (1999), p. 413

- Reihlen (1988), p. 17

- Rovan (1999), p. 411

- Demel & Puschner (1995), p. 222

- Demel & Puschner (1995), p. 217

- Nipperdey (1998), p. 33

- Griewank (2003), p. 14

- Türk, Lemke & Bruch (2006), p. 104

- Wehler (1987), p. 401

- Georg Pertz, pp. 449–450.

- Rovan (1999), p. 451

- Förster (2004), p. 299

- Georg Pertz, pp. 115–116.

- Förster (2004), p. 305

- Demel & Puschner (1995), p. 136

- Fehrenbach (1986), p. 109

- Demel & Puschner (1995), p. 138

- Demel & Puschner (1995), p. 141

- Nipperdey (1998), p. 36

- Demel & Puschner (1995), p. 143

- Büsch (1992), p. 22

- Kitchen (2006), p. 16

- Demel & Puschner (1995), p. 86

- Walther (1993), p. 227

- Rigaer Denkschrift in Demel & Puschner (1995), pp. 87–88

- Rigaer Denkschrift in Demel & Puschner (1995), p. 88

- Demel & Puschner (1995), p. 91

- Demel & Puschner (1995), p. 90

- Klein (1965), p. 128

- Büsch (1992), p. 287

- Fehrenbach (1986), p. 110

- Nipperdey (1998), p. 35

- Rovan (1999), p. 453

- Büsch (1992), p. 21

- Leo (1845), p. 491

- Fehrenbach (1986), pp. 109–115

- Nipperdey (1998), p. 34

- Demel & Puschner (1995), p. 145

- Demel & Puschner (1995), p. 146

- Demel & Puschner (1995), p. 148

- Botzenhart (1985), p. 46

- Demel & Puschner (1995), p. 137

- Demel & Puschner (1995), p. 150

- Demel & Puschner (1995), pp. 150–151

- Demel & Puschner (1995), p. 153

- Rovan (1999), p. 461

- Bussiek (2002), p. 29

- Fehrenbach (1986), p. 113

- Nipperdey (1998), p. 37

- Demel & Puschner (1995), p. 155

- Rovan (1999), p. 456

- Demel & Puschner (1995), p. 158

- Demel & Puschner (1995), p. 161

- Demel & Puschner (1995), p. 163

- Nipperdey (1998), pp. 38–40

- Müller-Osten (2007), p. 209

- Demel & Puschner (1995), p. 280

- Demel & Puschner (1995), p. 281

- Büsch (1992), p. 118

- Büsch (1992), p. 28

- Nipperdey (1998), p. 50

- Büsch (1992), p. 119

- Reihlen (1988), p. 20

- Fischer (1972), p. 119

- Wehler (1987), pp. 442–445

- Nipperdey (1998), pp. 40–43, 47

- Wehler (1987), p. 406

- Botzenhart (1985), p. 48

- Botzenhart (1985), p. 51

- Demel & Puschner (1995), p. 332

- Büsch (1992), p. 29

- Fehrenbach (1986), p. 116

- Demel & Puschner (1995), p. 337

- Fehrenbach (1986), p. 117

- Fehrenbach (1986), p. 118

- Büsch (1992), p. 94

- Fehrenbach (1986), p. 119

- Demel & Puschner (1995), p. 289

- Nipperdey (1998), p. 49

- Wehler (1987), pp. 429–432

- Demel & Puschner (1995), p. 211

- Demel & Puschner (1995), p. 212

- Jean Mondot, "L'émancipation des Juifs en Allemagne entre 1789 et 1815", in Knopper & Mondot (2008), p. 238

- Jean Mondot, "L'émancipation des Juifs en Allemagne entre 1789 et 1815", in Knopper & Mondot (2008), p. 237

- Demel & Puschner (1995), p. 214

- Rovan (1999), p. 460

- Wehler (1987), p. 408

- Demel & Puschner (1995), p. 364

- Demel & Puschner (1995), p. 365

- Demel & Puschner (1995), p. 363

- Demel & Puschner (1995), p. 368

- Giesecke (1991), p. 82

- Nipperdey (1998), p. 57

- Büsch (1992), p. 661

- Demel & Puschner (1995), p. 382

- Demel & Puschner (1995), p. 388

- Demel & Puschner (1995), p. 383

- Fehrenbach (1986), pp. 120–122

- Abenheim (1987), p. 210

- Millotat (2000), p. 52

- Demel & Puschner (1995), p. 392

- Lange (1857), p. 12

- Neugebauer & Busch (2006), p. 142

- Demel & Puschner (1995), p. 393

- Rovan (1999), p. 459

- Gumtau (1837), p. 3

- Neugebauer & Busch (2006), p. 197

- Millotat (2000), p. 53

- Braeuner (1863), p. 189

- Demel & Puschner (1995), p. 397

- Nipperdey (1998), pp. 50–56

- Neugebauer & Busch (2006), p. 144

- Roloff (1997), p. 787

- Klein (1965), p. 129

- Rovan (1999), p. 457

- Hensler & Twesten (1838), p. 328

- Hensler & Twesten (1838), p. 342

- Demel & Puschner (1995), p. 144

- Schüler-Springorum (1996), p. 37

- Vogel (1980), p. 14

- Radrizzani (2002), p. 127

- Demel & Puschner (1995), p. 60

- Demel & Puschner (1995), p. 414

- Fehrenbach (1986), pp. 235–239

- Fehrenbach (1986), pp. 239–241

- Vogel (1978)

- Koselleck (1967)

- Puhle (1980), p. 15, cited in Langewiesche (1994), p. 123

- Fehrenbach (1986), pp. 241–246

- Stamm-Kuhlmann (2001), p. 93

- Reihlen (1988), p. 79

Bibliography

- Abenheim, Donald (1987). Bundeswehr und Tradition: die Suche nach dem gültigen Erbe des deutschen Soldaten [Army and tradition: the search for the rightful heir of the German soldier] (in German). Oldenbourg.

- Botzenhart, Manfred (1985). Reform, Restauration, Krise, Deutschland 1789–1847. Neue historische Bibliothek. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp. ISBN 978-3-518-11252-6.

- Braeuner, R. (1863). Geschichte der preussischen Landwehr [History of the Prussian Army] (in German). Berlin.

- Bussiek, Dagmar (2002). Mit Gott für König und Vaterland! [With God for King and Country!] (in German). Münster.

- Büsch, Otto (1992). Das 19. Jahrhundert und Große Themen der Geschichte Preußens [Handbook of Prussian History 2: The 19th Century and Important Themes in Prussian History]. Handbuch der preußischen Geschichte (in German). 2. With contributions from Ilja Mieck, Wolfgang Neugebauer, Hagen Schulze, Wilhelm Treue and Klaus Zernack. Berlin: de Gruyter. ISBN 3-11-008322-1.

- Demel, Walter; Puschner, Uwe (1995). Von der Französischen Revolution bis zum Wiener Kongreß 1789–1815 [German History in Sources and Demonstration]. Deutsche Geschichte in Quellen und Darstellung (in German). 6. Stuttgart: Reclam. ISBN 978-3-15-017006-9.

- Dwyer, Philip G. (4 February 2014). The Rise of Prussia 1700-1830. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-88703-4.