Pernambucan revolt

The Pernambucan revolt of 1817 occurred in the province of Pernambuco in the Northeastern region of Brazil, and was sparked mainly by the decline of sugar production rates and the influence of the Freemasonry in the region. Other important reasons for the revolt include: the ongoing struggle for the independence of Spanish colonies all over in South America; the independence of the United States; the generally liberal ideas that came through all of Brazil the century before, including many French Philosophers, such as Charles Montesquieu and Jean-Jacques Rousseau; the actions of secret societies, which insisted on the liberation of the colony; the development of a distinct culture in Pernambuco.[1]

| Pernambucan revolt | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Blessing of the Flags of the 1817 Revolution, Antônio Parreiras | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| John VI of Portugal |

Domingos José Martins, Antônio Carlos de Andrada e Silva, Frei Caneca | ||||||

The movement was led by Domingos José Martins, with the support of Antônio Carlos de Andrada e Silva and Frei Caneca. Although a republic was declared, there were no measures adopted to abolish slavery.[2]

The Consulate General of the United States in Recife, America’s oldest diplomatic post in the Southern Hemisphere, publicly supported the Pernambucan revolutionaries.[3]

This revolution is also notable for being one of the first attempts to establish an independent government in Brazil, as it was preceded by the Inconfidência Mineira.

Background of the revolt

The revolt can be traced from the presence of the Portuguese royal family in Brazil, which mostly benefited the plantation owners, merchants and bureaucrats of the Central and Southern regions of the country. However, the inhabitants of other regions of the country, namely the Northeast, were not satisfied by the monarch's stay, given that southern Brazilians generally had knowledge of the favors and new privileges conceded to them by the Portuguese monarch from which they had received great wealth. However, the northern Brazilians were generally separated from the monarch and the benefits thereof, but, at the same time, had the responsibility to support him.[2]

Another group not content with the politics of the monarch, John VI of Portugal, were formed by military officials of Brazilian descent. In order to protect the cities and provide aid in military actions in Caiena and in the region of Prata, John brought troops from Portugal in order to organize military forces – however, he reserved the highest ranks for the Portuguese nobility. Because of this, the level of taxes steadily rose, but the colony was forced to maintain the expenditures of the military campaigns.[2]

The historical analyst, Maria Odila Silva Dias, remarked that "the costs related to the installation of public works rose the taxes above the exportation of sugar, tobacco and leather, creating a series of troubles that directly affected the capitanias of the North, while the Portuguese Court did not hesitate to overcharge or over recruit the people to support the current wars in Portugal, in Guiana and in the Prata region. For the governors and functionaries of serious capitanias, the same thing led the to Lisboa or to Rio."[2]

Troubles in the Northeast

.jpg)

The Northeastern region had already been previously affected by a famine causing a blow to cotton and sugar production in 1816, and creating another reason for the fervent desire for independence in that region. In Recife, the capital of Pernambuco, and in the principal ports of the region, the desire for independence and a general feeling of hostility for the Portuguese was particularly extreme. The general sentiment was described as the "Portuguese of New Lisbon" exploit and oppress the "Pernambucan patriots."[2]

Liberal ideas that entered Brazil by way with foreign travelers, books by foreign publications, and other sources incited the sentiment of revolt into the Pernambucans. Also, secret societies also had formed from the end of the 18th century, often in the form of mason stores, several of which had existed in Pernambuco – all of which served as locations for the spreading and general discussion of the so-called "infamous French ideas."[2]

In the peak of the revolt, one finds that the strongest Pernambucan patriots marked their identity in several methods – including drinking aguardente instead of wine and host made of wheat.[2]

Further patriotic feelings were expressed with the chants:

|

Quando a voz da pátria chama

|

When the voice of the fatherland calls

|

Napoleonic plans

Argentine historian Emilio Ocampo investigated the life of Carlos María de Alvear, and found British documents about a Bonapartist plot in Pernambuco to free Napoleón Bonaparte, and take him to some strategic location in South America, in order to create a new Napoleonic Empire. Alvear's plans were never carried out because of the defeat of the revolution.

Fall and Aftermath of the Revolt

The governor of Pernambuco, Caetano Pinto de Mirando Montenegro, had some knowledge of the plans of the revolutionaries, and thus sent out to arrest the primary leaders in the plot. These revolutionaries anticipated the danger to the movement, which began after the Pernambucan capitan, José de Barros Lima (nicknamed the Crowned Lion), killed the Portuguese officer assigned to arrest him.[1]

The revolutionaries organized a provisional government – with the leader aiming to extend the movement to other capitanias and obtain recognition from other nations. The revolt extended to Ceará, Paraíba and to Rio Grande do Norte, but was only able to survive two months before Recife was surrounded by sea and land by troops of the Portuguese monarch. The revolution, soon after, was dismantled.[1]

Before the fall of the movement, the revolutionaries sought out the support of the United States, Argentina and England, without success. Known casualties of the conflict include the eventual execution of the rebel leaders: Domingos José Martins, José Luis de Mendonça, Domingos Teotônio Jorge and the Catholic priests Miguelinho and Pedro de Sousa Tenório. The corpses of the condemned were later mutilated by having their hands and heads cut off. Other corpses were dragged by their heads to a burial ground.[4]

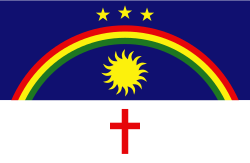

Flag of the Revolt

The general layout of the flag used by the revolutionaries still endures today, as the flag of the Brazilian state of Pernambuco. The first flag was formed from the requirement for a flag to replace the Portuguese flag that had been hauled down from the Recife fort after the provisional government took control of the city. The government originally considered hoisting the French tricolor, but instead appointed a committee under the chairmanship of Father João Ribeiro Pessoa to develop a design. The design was copied in watercolor by the Rio de Janeiro artist Antônio Álvares—a painting that still existed when Ribeiro was writing in the 1930s—essentially the same as the modern state flag with the field dark blue over white, a single star above the rainbow. The flags were produced by the tailor José Barbosa, who was also a captain in the militia. The first flag was publicly blessed by the dean of the Recife cathedral on 21 March 1817.[5]

In 1917, the same flag became the official banner of the current state.

According to its physical description, the flag's features signify the following: "The blue color in the upper rectangle symbolizes the grandeur of the Pernambuco sky. The color the white area is for peace. The three-colored rainbow represents the union of all the people of Pernambuco. The star indicates the state within the grouping of the Federation. The sun is the force and energy of Pernambuco, and finally, the cross represents our faith in justice and mutual understanding."[6]

See also

- Rebellions and revolutions in Brazil

- History of Brazil

- Northeastern Brazil

- Pernambuco

- Frei Caneca

References

- Revolução Pernambucana, Brazil Escola.com. Retrieved June 30, 2006.

- Revolução Pernambucana de 1817, multirio.rj.gov.br. Retrieved June 30, 2006.

- "U.S. Consulate General Recife". U.S. Embassy & Consulates in Brazil. Retrieved 2015-06-25.

- Revolução Pernambucana de 1817, multirio.rj.gov.br. Retrieved June 30, 2006.

- Pernambucan Revolution, 1817, From crwflags.com. Retrieved June 30, 2006.

- Pernambuco, From crwflags.com. Retrieved June 30, 2006.

External links

- Description of Revolt (in Portuguese)