Portland (shipwreck)

PS Portland was a large side-wheel paddle steamer, an ocean-going steamship with side-mounted paddlewheels. She was built in 1889 for passenger service between Boston, Massachusetts, and Portland, Maine. She is best known as the namesake of the infamous Portland Gale of 1898, a massive blizzard that struck coastal New England, claiming the lives of over 400 people and more than 150 vessels.[3]

_by_Jacobsen.gif) PS Portland at sea, by Antonio Jacobsen. | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | PS Portland |

| Namesake: | Portland, Maine |

| Owner: |

|

| Route: | Atlantic Ocean between Portland, Maine and Boston, Massachusetts |

| Builder: | New England Shipbuilding Co., Bath, Maine |

| Cost: | $250,000 |

| Launched: | October 14, 1889 |

| Homeport: | Portland, Maine |

| Fate: | Sank on 27 November 1898, during the Portland Gale |

| General characteristics | |

| Type: | Passenger paddle steamship |

| Tonnage: |

|

| Length: |

|

| Beam: |

|

| Draft: | 10 ft (3.0 m) |

| Depth of hold: | 15 ft 6 in (4.72 m) |

| Decks: | Three |

| Installed power: | (1) 62-inch-bore (1.6 m), 12-foot-stroke (3.7 m), 1,200-horsepower vertical-beam steam engine with (2) boilers |

| Propulsion: | (2) 35-foot-diameter (11 m) paddlewheels; each having (26) paddle buckets, 8 ft × 2 ft (2.4 m × 0.6 m), dipping 4 ft (1.2 m). |

| Speed: | 12 knots (22 km/h; 14 mph) |

| Capacity: | 156 staterooms accommodating 700 passengers; 400 tons freight[1] |

| Crew: | 63 |

PORTLAND (Shipwreck and Remains) | |

| |

| Nearest city | Gloucester, Massachusetts |

| NRHP reference No. | 04001473[2] |

| Added to NRHP | January 13, 2005 |

Construction and design

Portland's wooden hull was built by the Bath Iron Works in Bath, Maine. The 1200-horsepower vertical-beam steam engine was constructed by the Portland Company, with a bore, or cylinder diameter, measuring 5 ft 2 in (1.57 m) across, together with a 12 ft (3.7 m) stroke.[1] The ship's two iron boilers were constructed at the Bath Iron Works, also in Bath, Maine.

Portland was built for the Portland Steam Packet Company (later renamed Portland Steamship Company), at a cost of $250,000, to provide overnight passenger service between Boston and Portland.[1] She was one of New England's largest and most luxurious paddle steamers in existence at the time, and after nine years' solid performance, she had earned a reputation as a safe and dependable vessel.[4]

Final voyage and sinking

On November 27, 1898, Portland, having departed Boston earlier, was en route to Portland, Maine, following her traditional route. Unbeknownst to the crew, a powerful storm system was quickly traveling north, and Portland, despite her reputation as a remarkably safe vessel, was ill-equipped to handle such extreme conditions.

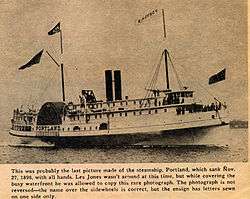

At some point during the storm, Portland sank off of Cape Ann with all hands, the exact number of which cannot be determined, as the only known passenger list went down with the ship. Initial newspaper accounts at the time estimated the loss as from 99 to 118 persons.[5][6] The bodies of only 16 crew and 35 passengers were ever recovered, but present-day estimates are that the Portland was carrying, in total, from 193 to 245 persons, including 63 crew.[7]

Her loss represented New England's greatest steamship disaster prior to the year 1900.[4]

Shipwreck

The shipwreck is lying 460 feet (140 m) below the surface of the Atlantic Ocean near Gloucester, Massachusetts, at an undisclosed location within the federally-protected Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary.[8] The site was first located in 1989 by John Fish and Arnold Carr of American Underwater Search and Survey. The find was confirmed in 2002 by a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration expedition that used ROV's to photograph the wreck.[9] The wreck was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2005.[10]

Divers explore The Portland wreckage

.jpg)

In 2008, five Massachusetts scuba divers became the first to reach the steamship, also known as the "Titanic of New England".[8] The divers made three successful dives, and reported that the wreck was strewn with artifacts, like stacks of dishes, mugs, wash basins and toilets, but no human remains. They did not, however, explore below the deck because of the danger.[8] Because of the depth of the wreck site, they reported that some of their dive lights imploded, and they could only explore the site for 10–15 minutes before needing to return to the surface.[8] The divers "were unable to retrieve artifacts" due to rules in place at the Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary.[8]

_02.jpg)

Purported site visit during WWII

An earlier claim of locating and reportedly visiting the wreck of the Portland arose from the last week of June 1945. A dive commissioned by noted author Edward Rowe Snow (who is also known as the Lighthouse Santa) supposedly occurred during the last week of June through the first week of July during the last year of the war. Snow supposedly recorded the affidavit of diver Al George, from Malden, Massachusetts, in pages 178-180 of his book Strange Tales from Nova Scotia to Cape Hatteras. According to the affidavit, George found the site by traveling to a location discovered by Captain Charles G. Carver of Rockland, Maine. The site is roughly identified as follows: "Highland Light bears 175 degrees true at a distance of 4.5 miles; the Pilgrim Monument, 6.25 miles away has a bearing of 210 degrees; Race Point Coast Guard Station, bearing 255 degrees, is seven miles distant."

According to diver George, recovery of artifacts would be cost-prohibitive, and nearly impossible given the status of the wreck. Even acknowledging the likely presence of uncut diamonds in the purser's safe, George assessed the chances of recovery as a losing financial proposition, based in part on how deeply entrenched in the sand the wreck was, and how widely dispersed the impact with the bottom had spread bits and pieces of the ship.

In light of more recent discovery, the accuracy of this entire account is highly questionable.

See also

References

- Stanton, Samuel Ward (1895). "American Steam Vessels". Great Lakes Maritime Society. p. 387. Archived from the original on 24 May 2008. Retrieved 27 October 2014.

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. April 15, 2008.

- Heit, Judi (19 October 2010). "Lost or Damaged Vessels". portlandgale.blogspot.com. The Portland Gale. Retrieved 27 October 2014.

- "Portland". Maritime Heritage. Gerry E. Studds Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary. 2 January 2009. Retrieved 27 October 2014.

- "Ninety-Nine Lives Go Out with the Wrecking of the Portland: Steamship Dashed to Pieces on the Rocky Shore of Cape Cod". Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. The San Francisco Call. Library of Congress. 30 November 1898. p. 1. Retrieved 26 October 2014.

The list given above numbers fifty-one passengers and forty-eight officers and crew.

- "The Portland Sunk; 118 lives lost; Steamer from Boston wrecked Sunday off Cape Cod". The New York Times. 30 November 1898. Retrieved 26 October 2014.

The steamer Portland, bound from Boston to Portland, went down off Truro, on the outside of Cape Cod, Sunday morning. Every man, woman, and child on board at the time of the disaster was drowned, in all 118.

- "Passenger and Crew Lost with the Steamship Portland". Maritime Heritage. Gerry E. Studds Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary. 5 January 2009. Retrieved 26 October 2014.

- "Divers reach steamship that sank off Mass. in 1898". USA Today. October 7, 2008. Retrieved 2008-10-07.

- "Location of the Portland Wreck confirmed by NOAA". NOAA. 29 August 2008.

- "Shipwreck in NOAA's Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary Added to National Register of Historic Places" (PDF). NOAA. 17 February 2005.

- Johansen, J. Benjamin (November 27, 1984). "The Mysterious Sinking Of A Maine-built Steamer". Bangor Daily News. p. 9. Retrieved 6 October 2013.