Plethodontidae

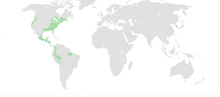

Plethodontidae, or lungless salamanders, are a family of salamanders. Most species are native to the Western Hemisphere, from British Columbia to Brazil, although a few species are found in Sardinia, Europe south of the Alps, and South Korea. In terms of number of species, they are by far the largest group of salamanders.[1]

| Lungless salamander | |

|---|---|

| |

| Batrachoseps attenuatus | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Amphibia |

| Order: | Urodela |

| Suborder: | Salamandroidea |

| Family: | Plethodontidae Gray, 1850 |

| Subgroups | |

| |

| |

| Native distribution of plethodontids (in green) | |

Biology

Adult lungless salamanders have four limbs, with four toes on the fore limbs, and usually with five on the hind limbs. Within many species, mating and reproduction occur solely on land. Accordingly, many species also lack an aquatic larval stage, a phenomenon known as direct development in which the offspring hatch as a fully-formed, miniature adults. Direct development is correlated with changes in the developmental characteristics of plethodontids compared to other families of salamanders including increases in egg size and duration of embryonic development. Additionally, the evolutionary loss of the aquatic larval stage is related to a diminishing dependence on aquatic habitats for reproduction. The lift of this constraint allowed widespread colonization and diversification within a broad number of terrestrial habitats which is a testament to the high success and proliferation of Plethodontidae.[2]

Many species have a projectile tongue and hyoid apparatus, which they can fire almost a body length at high speed to capture prey.

Measured in individual numbers, they are very successful animals where they occur. In some places, they make up the dominant biomass of vertebrates.[3] An estimated 1.88 billion individuals of the southern redback salamander inhabit just one district of Mark Twain National Forest alone, about 1,400 tons of biomass.[4] Due to their modest size and low metabolism, they are able to feed on prey such as springtails, which are usually too small for other terrestrial vertebrates. This gives them access to a whole ecological niche with minimal competition from other groups.

The earliest known fossil remains referred to this family are known from the Late Cretaceous of Wyoming.[5]

Courtship and Mating

Plethodontids exhibit highly stereotyped and complex mating behaviors and courtship rituals that are not present in any other salamander family. Mating behavior tends to be uniform among all plethodontids and typically involves a tail-straddle walk in which the female orients her head at the base of the male's tail while also straddling the tail with her body. The male will twist his body around and deposit a sperm capsule known as the spermatophore on the substrate in front of the female's snout. As the male leads the female over the spermatophore with his tail, the female lowers her cloaca onto the spermatophore and lodges the sperm mass inside while leaving the base of the spermatophore on the ground.[6]

Within many species of plethodontidae, the courtship ritual is often accompanied by transfer of male pheromones during the tail-straddling walk. During the breeding period, males will grow enlarged anterior teeth used to scratch the female's skin on her head as a part of the courtship ritual. Subsequently, the male will rub pheromones onto the abraded spot which are secreted from a pad of tissue called the mental gland located underneath the male's chin.[6]

Courtship pheromones greatly increase male mating success for a variety of reasons. Overall, the pheromone secretions increase female receptivity to courtship and sperm transfer. This not only increases the likelihood of successful mating with a specific female, but also shortens the duration of courtship which is important because it minimizes the chance of the male being interrupted by other competing males.[7]

Respiration

A number of features distinguish the plethodontids from other salamanders. Most significantly, they lack lungs, conducting respiration through their skin, and the tissues lining their mouths.[1]

Chemoreception

Another distinctive feature is the presence of a vertical slit between the nostril and upper lip, known as the "nasolabial groove". The groove is lined with glands, and enhances the salamander's chemoreception which is correlated with a higher degree of olfactory lobe and nasal mucous membrane development in plethodontids.[1][8] The presence of this specialized structure is likely related to the absence of lungs in these salamanders. Though some lunged salamanders do exhibit similar structures, they are reduced in size and are not arranged near the nostrils (i.e. nares) in the same fashion as plethodontids. Due to the fact that plethodontids cannot generate air pressure via expulsion of air from the lungs and through the nares, they are presented with the challenge of removing water and debris from the nasal passages which has the potential to significantly limit olfactory processes. As such, the nasolabial grooves are structured in a way that maximizes drainage from the nose. The groove is deeper and more narrow directly around the nares and the orifices of the glands are slightly elevated both of which aid in the gravitational flow of fluid from the nares and nasal depression. Additionally, the nasolabial glands around the margins of the nares secrete a fatty film which further encourages the removal of water from the nasal passages due to differences in polarity between water and the lipid secretions.[8]

Taxonomy

The family Plethodontidae consists of two extant subfamilies and about 478 species divided among these genera, making up the majority of known salamander species:

| Subfamily | Genus, scientific name, and author | Common name | Species |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hemidactyliinae Hallowell, 1856 | |||

| Aquiloeurycea Rovito, Parra-Olea, Recuero, and Wake, 2015 | 6 | ||

| Batrachoseps Bonaparte, 1839 | Slender salamanders | 21 | |

| Bolitoglossa Duméril, Bibron & Duméril, 1854 | Tropical climbing salamanders | 132 | |

| Bradytriton Wake & Elias, 1983 | Finca Chiblac salamander | 1 | |

| Chiropterotriton Taylor, 1944 | Splay-foot salamanders | 18 | |

| Cryptotriton García-París & Wake, 2000 | Hidden salamanders | 7 | |

| Dendrotriton Wake & Elias, 1983 | Bromeliad salamanders | 8 | |

| Eurycea Rafinesque, 1822 | North American brook salamanders | 32 | |

| Gyrinophilus Cope, 1869 | Spring salamanders | 4 | |

| Hemidactylium Tschudi, 1838 | Four-toed salamanders | 1 | |

| Isthmura Dubois and Raffaelli, 2012 | 7 | ||

| Ixalotriton Wake and Johnson, 1989 | Jumping salamanders | 2 | |

| Nototriton Wake & Elias, 1983 | Moss salamanders | 20 | |

| Nyctanolis Elias & Wake, 1983 | Long-limbed salamanders | 1 | |

| Oedipina Keferstein, 1868 | Worm salamanders | 38 | |

| Parvimolge Taylor, 1944 | Tropical dwarf salamanders | 1 | |

| Pseudoeurycea Taylor, 1944 | False brook salamanders | 39 | |

| Pseudotriton Tschudi, 1838 | Mud and red salamanders | 3 | |

| Stereochilus Cope, 1869 | Many-lined salamanders | 1 | |

| Thorius Cope, 1869 | Minute salamanders | 29 | |

| Urspelerpes Camp, Peterman, Milanovich, Lamb, Maerz, and Wake, 2009 | Patch-nosed salamanders | 1 | |

| Plethodontinae Gray, 1850 | |||

| Aneides Baird, 1851 | Climbing salamanders | 9 | |

| Desmognathus Baird, 1850 | Dusky salamanders | 24 | |

| Ensatina Gray, 1850 | Ensatinas | 1 | |

| Hydromantes Gistel, 1848 | Web-toed salamanders | 5 | |

| Karsenia Min, Yang, Bonett, Vieites, Brandon & Wake, 2005 | Korean crevice salamanders | 1 | |

| Phaeognathus Highton, 1961 | Red Hills salamanders | 1 | |

| Plethodon Tschudi, 1838 | Slimy and mountain salamanders | 57 | |

| Speleomantes Dubois, 1984 | European cave salamanders | 8 | |

Following a major revision in 2006, the genus Haideotriton was found to be a synonym of Eurycea, while the genus Lineatriton were made synonyms of Pseudoeurycea.[9]

Conservation Status

| Status | Number of Species |

|---|---|

| Least Concern | 94 |

| Near Threatened | 39 |

| Vulnerable | 60 |

| Endangered | 88 |

| Critically Endangered | 68 |

| Extinct | 1 |

| Data Deficient | 40 |

References

- Lanza, B., Vanni, S., & Nistri, A. (1998). Cogger, H.G. & Zweifel, R.G. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Reptiles and Amphibians. San Diego: Academic Press. pp. 74–75. ISBN 0-12-178560-2.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Lewis, Zachary R.; Kerney, Ryan; Hanken, James (2011). "Lung development in lungless salamanders!". Developmental Biology. 356 (1): 250–251. doi:10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.05.560. ISSN 0012-1606.

- Hairston, N.G., Sr. 1987. Community ecology and salamander guilds. Cambridge University Press. Cambridge.

- Salamanders a more abundant food source in forest ecosystems than previously thought

- "Fossilworks: Plethodontidae". fossilworks.org. Retrieved 2019-05-31.

- Reproductive biology and phylogeny of Urodela. Sever, David M. Enfield, NH: Science Publishers. 2003. pp. 383–424. ISBN 978-1-57808-645-0. OCLC 427511083.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Houck, Lynne D.; Reagan, Nancy L. (1990). "Male courtship pheromones increase female receptivity in a plethodontid salamander". Animal Behaviour. 39 (4): 729–734. doi:10.1016/s0003-3472(05)80384-7. ISSN 0003-3472.

- Brown, Charles E.; Martof, Bernard S. (1966-10-01). "The Function of the Naso-Labial Groove of Plethodontid Salamanders". Physiological Zoology. 39 (4): 357–367. doi:10.1086/physzool.39.4.30152358. ISSN 0031-935X.

- Frost et al. 2006. THE AMPHIBIAN TREE OF LIFE (http://digitallibrary.amnh.org/dspace/bitstream/2246/5781/1/B297.pdf)

- IUCN RedList, (2020). Plethodontidae. Retrieved from https://www.iucnredlist.org/search?taxonomies=101246&searchType=species