Squanto

Tisquantum (/tɪsˈkwɒntəm/; c. 1585 (±10 years?) – late November 1622 O.S.), more commonly known by the diminutive variant Squanto (/ˈskwɒntoʊ/), was a member of the Patuxet tribe best known for being an early liaison between the Indian population in Southern New England and the Mayflower Pilgrims who made their settlement at the site of Squanto's former summer village. The Patuxet tribe had lived on the western coast of Cape Cod Bay, but they were wiped out by an epidemic infection.

Squanto | |

|---|---|

1911 illustration of Tisquantum ("Squanto") teaching the Plymouth colonists to plant maize. | |

| Born | Tisquantum c. 1585 Patuxet (now Plymouth, Massachusetts) |

| Died | late November 1622 O.S. Mamamoycke (or Monomoit) (now Chatham, Massachusetts) |

| Nationality | Patuxet |

| Known for | Guidance, advice, and translation services to the Mayflower settlers |

Squanto was kidnapped by English explorer Thomas Hunt who carried him to Spain, where he sold him in the city of Málaga. He was among a number of captives bought by local monks who focused on their education and evangelization. Squanto eventually traveled to England, then returned to America in 1619 to his native village, only to find that his tribe had been wiped out by an epidemic infection; Squanto was the last of the Patuxets.

The Mayflower landed in Cape Cod Bay in 1620, and Squanto worked to broker peaceable relations between the Pilgrims and the local Pokanokets. He played a key role in the early meetings in March 1621, partly because he spoke English. He then lived with the Pilgrims for 20 months, acting as a translator, guide, and advisor. He introduced the settlers to the fur trade and taught them how to sow and fertilize native crops; this proved vital, because the seeds mostly failed which the Pilgrims had brought from England. As food shortages worsened, Plymouth Colony Governor William Bradford relied on Squanto to pilot a ship of settlers on a trading expedition around Cape Cod and through dangerous shoals. During that voyage, Squanto contracted what Bradford called an "Indian fever". Bradford stayed with him for several days until he died, which Bradford described as a "great loss".

A considerable mythology has grown up around Squanto over time, largely because of early praise by Bradford and owing to the central role that the Thanksgiving festival of 1621 plays in American folk history. Squanto was a practical advisor and diplomat, rather than the noble savage that later myth portrayed.

Name

Documents from the 17th century variously render the spelling of Tisquantum's name as Tisquantum, Tasquantum, and Tusquantum, and alternately call him Squanto, Squantum, Tantum, and Tantam.[1] Even the two Mayflower settlers who dealt with him closely spelled his name differently; Bradford nicknamed him "Squanto", while Edward Winslow invariably referred to him as Tisquantum, which historians believe was his proper name.[2] One suggestion of the meaning is that it is derived from the Algonquian expression for the rage of the Manitou, "the world-suffusing spiritual power at the heart of coastal Indians' religious beliefs".[3] Manitou was "the spiritual potency of an object" or "a phenonmenon", the force which made "everything in Nature responsive to man".[4] Other suggestions have been offered,[lower-alpha 1] but all involve some relationship to beings or powers that the colonists associated with the devil or evil.[lower-alpha 2] It is, therefore, unlikely that it was his birth name, rather than one that he acquired or assumed later in life, but there is no historical evidence on this point. The name may suggest, for example, that he underwent special spiritual and military training, and was selected for his role as liaison with the settlers in 1620 for that reason.[7]

Early life and years of bondage

Almost nothing is known of Squanto's life before his first contact with Europeans, and even when and how that first encounter took place is subject to contradictory assertions.[8] First-hand descriptions of him written between 1618 and 1622 do not remark on his youth or old age, and Salisbury has suggested that he was in his twenties or thirties when he embarked to Spain in 1614.[9] If that was the case, he would have been born around 1585 (±10 years).

Squanto's native culture

The tribes who lived in southern New England at the beginning of the 17th century referred to themselves as Ninnimissinuok, a variation of the Narragansett word Ninnimissinnȗwock meaning "people" and signifying "familiarity and shared identity".[10] Squanto's tribe of the Patuxets occupied the coastal area west of Cape Cod Bay, and he told an English trader that the Patuxets once numbered 2,000.[11] They spoke a dialect of Eastern Algonquian common to tribes as far west as Narragansett Bay.[lower-alpha 3] The various Algonquian dialects of Southern New England were sufficiently similar to allow effective communications.[lower-alpha 4] The term patuxet refers to the site of Plymouth, Massachusetts and means "at the little falls".[lower-alpha 5] referencing Morison.[16] Morison gives Mourt's Relation as authority for both assertions.

The annual growing season in southern Maine and Canada was not long enough to produce maize harvests, and the Indian tribes in those areas were required to live a fairly nomadic existence,[17] while the southern New England Algonquins were "sedentary cultivators" by contrast.[18] They grew enough for their own winter needs and for trade, especially to northern tribes, and enough to relieve the colonists' distress for many years when their harvests were insufficient.[19]

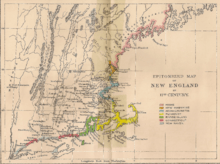

.jpg)

The groups that made up the Ninnimissinuok were presided over by one or two sachems.[20] The chief functions of the sachems were to allocate land for cultivation,[21] to manage the trade with other sachems or more distant tribes,[22] to dispense justice (including capital punishment),[23] to collect and store tribute from harvests and hunts,[24] and leading in war.[25]

Sachems were advised by "principal men" of the community called ahtaskoaog, generally called "nobles" by the colonists. Sachems achieved consensus through the consent of these men, who probably also were involved in the selection of new sachems. One or more principal men were generally present when sachems ceded land.[26] There was a class called the pniesesock among the Pokanokets which collected the annual tribute to the sachem, led warriors into battle, and had a special relationship with their god Abbomocho (Hobbomock) who was invoked in pow wows for healing powers, a force that the colonists equated with the devil.[lower-alpha 6] The priest class came from this order, and the shamans also acted as orators, giving them political power within their societies.[31] Salisbury has suggested that Squanto was a pniesesock.[7] This class may have produced something of a praetorian guard, equivalent to the "valiant men" described by Roger Williams among the Narragansetts, the only Southern New England society with an elite class of warriors.[32] In addition to the class of commoners (sanops), there were outsiders who attached themselves to a tribe. They had few rights except the expectation of protection against any common enemy.[31]

Contact with Europeans

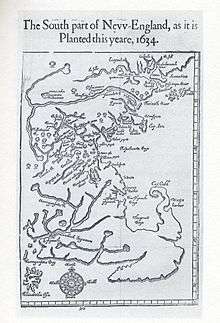

The Ninnimissinuok had sporadic contact with European explorers for nearly a century before the landing of the Mayflower in 1620. The fishermen off the Newfoundland banks from Bristol, Normandy, and Brittany began making annual spring visits beginning as early as 1581 to bring cod to Southern Europe.[33] These early encounters had long-term effects. Europeans might have introduced diseases[lower-alpha 7] for which the Indian population had no resistance. When the Mayflower arrived, the Pilgrims discovered that an entire village was devoid of inhabitants.[35] European fur trappers traded with different tribes, and this encouraged intertribal rivalries and hostilities.[36]

The first kidnappings

In 1605, George Weymouth set out on an expedition to explore the possibility of settlement in upper New England, sponsored by Henry Wriothesley and Thomas Arundell.[37] They had a chance encounter with a hunting party, then decided to kidnap a number of Indians. The capture of Indians was "a matter of great importance for the full accomplement of our voyage".[38]

They took five captives to England and gave three to Sir Ferdinando Gorges. Gorges was an investor in the Weymouth voyage and became the chief promoter of the scheme when Arundell withdrew from the project.[39] Gorges wrote of his delight in Weymouth's kidnapping, and named Squanto as one of the three given to him.

Captain George Weymouth, having failed at finding a Northwest Passage, happened into a River on the Coast of America, called Pemmaquid, from whence he brought five of the Natives, three of whose names were Manida, Sellwarroes, and Tasquantum, whom I seized upon, they were all of one Nation, but of severall parts, and severall Families; This accident must be acknowledged the meanes under God of putting on foote, and giving life to all our Plantations.[40]

Circumstantial evidence makes nearly impossible the claim that it was Squanto among the three taken by Gorges,[lower-alpha 8] Adams maintains that "it is not supposable that a member of the Pokánoket tribe would be passing the summer of 1605 in a visit among his deadly enemies the Tarratines, whose language was not even intelligible to him … and be captured as one of a party of them in the way described by Rosier".[41] and no modern historian entertains this as fact.[lower-alpha 9]

Squanto's abduction

.jpg)

In 1614, an English expedition headed by John Smith sailed along the coast of Maine and Massachusetts Bay collecting fish and furs. Smith returned to England in one of the vessels and left Thomas Hunt in command of the second ship. Hunt was to complete the haul of cod and proceed to Málaga, Spain, where there was a market for dried fish,[42] but Hunt decided to enhance the value of his shipment by adding human cargo. He sailed to Plymouth harbor ostensibly to trade with the village of Patuxet, where he lured 20 Indians aboard his vessel under promise of trade, including Squanto.[42] Once aboard, they were confined and the ship sailed across Cape Cod Bay where Hunt abducted seven more from the Nausets.[43] He then set sail for Málaga.

Smith and Gorges both disapproved of Hunt's decision to enslave the Indians.[44] Gorges worried about the prospect of "a warre now new begun between the inhabitants of those parts, and us",[45] although he seemed mostly concerned about whether this event had upset his gold-finding plans with Epenow on Martha's Vineyard.[46] Smith suggested that Hunt got his just deserts because "this wilde act kept him ever after from any more imploiment to those parts."[42]

According to Gorges, Hunt took the Indians to the Strait of Gibraltar where he sold as many as he could. But the "Friers (sic) of those parts" discovered what he was doing, and they took the remaining Indians to be "instructed in the Christian Faith; and so disappointed this unworthy fellow of his hopes of gaine".[47] No records show how long Squanto lived in Spain, what he did there, or how he "got away for England", as Bradford puts it.[48] Prowse asserts that he spent four years in slavery in Spain and was then smuggled aboard a ship belonging to Guy's colony, taken to Spain, and then to Newfoundland.[49] Smith attested that Squanto lived in England "a good time", although he does not say what he was doing there.[50] Plymouth Governor William Bradford knew him best and recorded that he lived in Cornhill, London with "Master John Slanie".[51] Slany was a merchant and shipbuilder who became another of the merchant adventurers of London hoping to make money from colonizing projects in America and was an investor in the East India Company.

Squanto's return to New England

According to the report by the Plymouth Council for New England in 1622, Squanto was in Newfoundland "with Captain Mason Governor there for the undertaking of that Plantation".[52] Thomas Dermer was at Cuper's Cove in Conception Bay,[53] an adventurer who had accompanied Smith on his abortive 1615 voyage to New England. Squanto and Dermer talked of New England while in Newfoundland, and Squanto persuaded him that he could make his fortune there, and Dermer wrote Gorges and requested that Gorges send him a commission to act in New England.

Toward the end of 1619, Dermer and Squanto sailed down the New England coast to Massachusetts Bay. They discovered that all inhabitants had died in Squanto's home village at Patucket, so they moved inland to the village of Nemasket. Dermer sent Squanto[54] to the village of Pokanoket near Bristol, Rhode Island, seat of Chief Massasoit. A few days later, Massasoit arrived at Nemasket along with Squanto and 50 warriors. It is not known whether Squanto and Massasoit had met prior to these events, but their interrelations can be traced at least to this date.

Dermer returned to Nemasket in June 1620, but this time he discovered that the Indians there bore "an inveterate malice to the English", according to a June 30, 1620 letter transcribed by Bradford. This sudden and dramatic change from friendliness to hostility was due to an incident the previous year, when a European coastal vessel lured some Indians on board with the promise of trade, only to mercilessly slaughter them. Dermer wrote that "Squanto cannot deny but they would have killed me when I was in Nemask, had he not entreated hard for me."[55]

Some time after this encounter, Indians attacked Dermer and Squanto and their party on Martha's Vineyard, and Dermer received "14 mortal wounds in the process".[56] He fled to Virginia where he died, but nothing is known of Squanto's life until he suddenly appears to the Pilgrims in Plymouth Colony.

Plymouth Colony

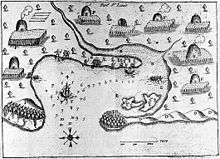

.jpg)

The Massachusett Indians were north of Plymouth Colony, led by Chief Massasoit, and the Pokanoket tribe were north, east, and south. Squanto was living with the Pokanokets, as his native tribe of the Patuxets had been effectively wiped out prior to the arrival of the Mayflower; indeed, the Pilgrims had established their former habitation as the site of Plymouth Colony.[57] The Narragansett tribe inhabited Rhode Island.

Massasoit was faced with the dilemma whether to form an alliance with the Plymouth colonists, who might protect him from the Narragansetts, or try to put together a tribal coalition to drive out the colonists. To decide the issue, according to Bradford's account, "they got all the Powachs of the country, for three days together in a horrid and devilish manner, to curse and execrate them with their conjurations, which assembly and service they held in a dark and dismal swamp."[58] Philbrick sees this as a convocation of shamans brought together to drive the colonists from the shores by supernatural means.[lower-alpha 10]. Squanto had lived in England, and he told Massassoit "what wonders he had seen" there. He urged Massasoit to become friends with the Plymouth colonists, because his enemies would then be "Constrained to bowe to him".[59] Also connected to Massasoit was Samoset, a minor Abenakki sachem who hailed from the Muscongus Bay area of Maine. Samoset had learned English, most likely from former dealings with English fisherman off the coast of Maine.

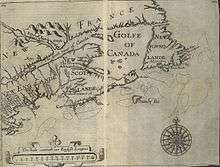

.jpg)

On Friday, March 16, the settlers were conducting military training when Samoset "boldly came alone" into the settlement.[60] The colonists were initially alarmed, but he immediately set their fears at ease by asking for beer.[61] He spent the day giving them intelligence of the surrounding tribes, then stayed for the night. The next day, Samoset returned with five men all bearing deer skins and one cat skin. The settlers entertained them but refused to trade with them because it was the Sabbath, although they encouraged them to return with more furs. All left but Samoset who lingered until Wednesday, feigning illness.[62] He returned once more on Thursday, March 22, this time with Squanto. The men brought important news: Massasoit, his brother Quadrquina, and all of their men were close by. After an hour's discussion, the sachem and his train of 60 men appeared on Strawberry Hill. Both the colonists and Massasoit's men were unwilling to make the first move, but Squanto shuttled between the groups and effected the simple protocol which permitted Edward Winslow to approach the sachem. Winslow, with Squanto as translator, proclaimed the loving and peaceful intentions of King James and the desire of their governor to trade and make peace with him.[63] After Massasoit ate, Miles Standish led him to a house which was furnished with pillows and a rug. Governor Carver then came "with Drumme and Trumpet after him" to meet Massasoit. The parties ate together, then negotiated a treaty of peace and mutual defense between the Plymouth settlers and the Pokanoket people.[64] According to Bradford, "all the while he sat by the Governour, he trembled for feare".[65] Massasoit's followers applauded the treaty,[65] and the peace terms were kept by both parties during Massasoit's lifetime.

Squanto as guide to frontier survival

Massasoit and his men left the day after the treaty, but Samoset and Squanto remained.[66] Squanto and Bradford developed a close friendship, and Bradford relied on him heavily during his years as governor of the colony. Bradford considered him "a special instrument sent of God for their good beyond their expectation".[67] Squanto instructed them in survival skills and acquainted them with their environment. "He directed them how to set their corn, where to take fish, and to procure other commodities, and was also their pilot to bring them to unknown places for their profit, and never left them till he died."[67]

The day after Massasoit left Plymouth, Squanto spent the day at Eel River treading eels out of the mud with his feet. The bucketful of eels he brought back were "fat and sweet".[68] Collection of eels became part of the settlers' annual practice. But Bradford makes special mention of Squanto's instruction concerning local horticulture. He had arrived at the time of planting for that year's crops, and Bradford said that "Squanto stood them in great stead, showing them both the manner how to set it, and after how to dress and tend it."[69] Bradford wrote that Sqanto showed them how to fertilize exhausted soil:

He told them, except they got fish and set with it [corn seed] in these old grounds it would come to nothing. And he showed them that in the middle of April they should have store enough [of fish] come up the brook by which they began to build, and taught them how to take it, and where to get other provisions necessary for them. All of which they found true by trial and experience.[70]

Edward Winslow made the same point about the value of Indian cultivation methods in a letter to England at the end of the year:

We set the last Spring some twentie Acres of Indian Corne, and sowed some six Acres of Barly and Pease; and according to the manner of the Indians, we manured our ground with Herings or rather Shadds, which we have in great abundance, and take with great ease at our doores. Our Corn did prove well, & God be praysed, we had a good increase of Indian-Corne, and our Barly indifferent good, but our Pease were not worth the gathering, for we feared they were too late sowne.[71]

The method shown by Squanto became the regular practice of the settlers.[72] Squanto also showed the Plymouth colonists how they could obtain pelts with the "few trifling commodities they brought with them at first". Bradford reported that there was not "any amongst them that ever saw a beaver skin till they came here and were informed by Squanto".[73] Fur trading became an important way for the colonists to pay off their financial debt to their financial sponsors in England.

Squanto's role in settler diplomacy

Thomas Morton stated that Massasoit was freed as a result of the peace treaty and "suffered [Squanto] to live with the English",[74] and Squanto remained loyal to the colonists. One commentator has suggested that the loneliness occasioned by the wholesale extinction of his people was the motive for his attachment to the Plymouth settlers.[75] Another has suggested that it was self-interest that he conceived while in the captivity of the Pokanoket.[76] The settlers were forced to rely on Squanto because he was the only means by which they could communicate with the surrounding Indians, and he was involved in every contact for the 20 months that he lived with them.

Mission to Pokanoket

Plymouth Colony decided in June that a mission to Massasoit in Pokatoket would enhance their security and reduce visits by Indians who drained their food resources. Winslow wrote that they wanted to ensure that the peace treaty was still valued by the Pokanoket and to reconnoiter the surrounding country and the strength of the various tribes. They also hoped to show their willingness to repay the grain that they took on Cape Cod the previous winter, in the words of Winslow to "make satisfaction for some conceived injuries to be done on our parts".[77]

Governor Bradford selected Edward Winslow and Stephen Hopkins to make the journey with Squanto. They set off on July 2[lower-alpha 11] carrying a "Horse-mans coat" as a gift for Massasoit made of red cotton and trimmed "with a slight lace". They also took a copper chain and a message expressing their desire to continue and strengthen the peace between the two peoples and explaining the purpose of the chain. The colony was uncertain of their first harvest, and they requested that Massasoit restrain his people from visiting Plymouth as frequently as they had—though they wished always to entertain any guest of Massasoit. So if he gave anyone the chain, they would know that the visitor was sent by him and they would always receive him. The message also attempted to explain the settlers' conduct on Cape Cod when they took some corn, and they requested that he send his men to the Nauset to express the settlers' wish to make restitution. They departed at 9 a.m.,[81] and traveled for two days meeting friendly Indians along the way. When they arrived at Pokanoket, Massasoit had to be sent for, and Winslow and Hopkins gave him a salute with their muskets when he arrived, at Squanto's suggestion. Massasoit was grateful for the coat and assured them on all points that they made. He assured them that his 30 tributary villages would remain in peace and would bring furs to Plymouth. The colonists stayed for two days,[82] then sent Squanto off to the various villages to seek trading partners for the English while they returned to Plymouth.

Mission to the Nauset

Winslow writes that young John Billington had wandered off and had not returned for five days. Bradford sent word to Massasoit, who made inquiry and found that the child had wandered into a Manumett village, who turned him over to the Nausets.[83] Ten settlers set out and took Squanto as a translator and Tokamahamon as "a special friend," in Winslow's words. They sailed to Cummaquid by evening and spent the night anchored in the bay. In the morning, the two Indians on board were sent to speak to two Indians who were lobstering. They were told that the boy was at Nauset, and the Cape Cod Indians invited all the men to take food with them. The Plymouth colonists waited until the tide allowed the boat to reach the shore, and then they were escorted to sachem Iyanough who was in his mid-20s and "very personable, gentle, courteous, and fayre conditioned, indeed not like a Savage", in Winslow's words. The colonists were lavishly entertained, and Iyanough even agreed to accompany them to the Nausets.[84] While in this village, they met an old woman, "no lesse then an hundred yeeres old", who wanted to see the colonists, and she told them of how her two sons were kidnapped by Hunt at the same time that Squanto was, and she had not seen them since. Winslow assured her that they would never treat Indians that way and "gave her some small trifles, which somewhat appeased her".[85] After their lunch, the settlers took the boat to Nauset with the sachem and two of his band, but the tide prevented the boat from reaching shore, so the colonists sent Inyanough and Squanto to meet Nauset sachem Aspinet. The colonists remained in their shallop and Nauset men came "very thick" to entreat them to come ashore, but Winslow's party was afraid because this was the very spot of the First Encounter. One of the Indians whose corn they had taken the previous winter came out to meet them, and they promised to reimburse him.[lower-alpha 12] That night, the sachem came with more than 100 men, the colonists estimated, and he bore the boy out to the shallop. The colonists gave Aspinet a knife and one to the man who carried the boy to the boat. By this, Winslow considered that "they made peace with us."

The Nausets departed, but the colonists learned (probably from Squanto) that the Narragansetts had attacked the Pokanokets and taken Massasoit. This caused great alarm because their own settlement was not well guarded given that so many were on this mission. The men tried to set off immediately, but they had no fresh water. After stopping again at Iyanough's village, they set off for Plymouth.[87] This mission resulted in a working relationship between the Plymouth settlers and the Cape Cod Indians, both the Nausets and the Cummaquid, and Winslow attributed that outcome to Squanto.[88] Bradford wrote that the Indians whose corn they had taken the previous winter came and received compensation, and peace generally prevailed.[89]

Action to save Squanto in Nemasket

The men returned to Plymouth after rescuing the Billington boy, and it was confirmed to them that Massasoit had been ousted or taken by the Narragansetts.[90] They also learned that Corbitant, a Pocasset[91] sachem formerly tributary to Massasoit, was at Nemasket attempting to pry that band away from Massasoit. Corbitant was reportedly also railing against the peace initiatives that the Plymouth settlers had just had with the Cummaquid and the Nauset. Squanto was an object of Corbitant's ire because of his role in mediating peace with the Cape Cod Indians, but also because he was the principal means by which the settlers could communicate with the Indians. "If he were dead, the English had lost their tongue," he reportedly said.[92] Hobomok was a Pokanoket pniese residing with the colonists,[lower-alpha 13] and he had also been threatened for his loyalty to Massasoit.[94] Squanto and Hobomok were evidently too frightened to seek out Massasoit, and instead went to Nemasket to find out what they could. Tokamahamon, however, went looking for Massasoit. Corbitant discovered Squanto and Hobomok at Nemasket and captured them. He held Squanto with a knife to his breast, but Hobomok broke free and ran to Plymouth to alert them, thinking that Squanto had died.[95]

Governor Bradford organized an armed task force of about a dozen men under the command of Miles Standish,[96][97] and they set off before daybreak on August 14[98] under the guidance of Hobomok. The plan was to march the 14 miles to Nemasket, rest, and then take the village unawares in the night. The surprise was total, and the villagers were terrified. The colonists could not make the Indians understand that they were only looking for Corbitant, and there were "three sore wounded" trying to escape the house.[99] The colonists realized that Squanto was unharmed and staying in the village, and that Corbitant and his men had returned to Pocaset. The colonists searched the dwelling, and Hobomok got on top of it and called for Squanto and Tiquantum, both of whom came. The settlers commandeered the house for the night. The next day, they explained to the village that they were interested only in Corbitant and those supporting him. They warned that they would exact retribution if Corbitant continued threatening them, or if Massasoit did not return from the Narragansetts, or if anyone attempted harm to any of Massasoit's subjects, including Squanto and Hobomok. They then marched back to Plymouth with Nemasket villagers helping bear their equipment.[100]

Bradford wrote that this action resulted in a firmer peace, and that "divers sachems" congratulated the settlers and more came to terms with them. Even Corbitant made his peace through Massasoit.[98] Nathaniel Morton later recorded that nine sub-sachems came to Plymouth on September 13, 1621 and signed a document declaring themselves "Loyal Subjects of King James, King of Great Britain, France and Ireland".[101]

Mission to the Massachuset people

The Plymouth colonists resolved to meet with the Massachusetts Indians who had frequently threatened them.[102] On August 18, a crew of ten settlers set off around midnight, with Squanto and two other Indians as interpreters, hoping to arrive before daybreak. But they misjudged the distance and were forced to anchor off shore and stay in the shallop over the next night.[103] Once ashore, they found a woman coming to collect the trapped lobsters, and she told them where the villagers were. Squanto was sent to make contact, and they discovered that the sachem presided over a considerably reduced band of followers. His name was Obbatinewat, and he was a tributary of Massasoit. He explained that his current location within Boston harbor was not a permanent residence since he moved regularly to avoid the Tarentines[lower-alpha 14] and the Squa Sachim (the widow of Nanepashemet).[105] Obbatinewat agreed to submit himself to King James in exchange for the colonists' promise to protect him from his enemies. He also took them to see the squa sachem across the Massachusetts Bay.

On Friday, September 21, the colonists went ashore and marched a house where Nanepashemet was buried.[106] They remained there and sent Squanto and another Indian to find the people. There were signs of hurried removal, but they found the women together with their corn and later a man who was brought trembling to the settlers. They assured him that they did not intend harm, and he agreed to trade furs with them. Squanto urged the colonists to simply "rifle" the women and take their skins on the ground, that "they are a bad people and oft threatned you,"[107] but the colonists insisted on treating them fairly. The women followed the men to the shallop, selling them everything that they had, including the coats off their backs. As the colonists shipped off, they noticed that the many islands in the harbor had been inhabited, some cleared entirely, but all the inhabitants had died.[108] They returned with "a good quantity of beaver", but the men who had seen Boston Harbor expressed their regret that they had not settled there.[98]

The peace regime that Squanto helped achieve

During the fall of 1621 the Plymouth settlers had every reason to be contented with their condition, less than one year after the "starving times". Bradford expressed the sentiment with biblical allusion[lower-alpha 15] that they found "the Lord to be with them in all their ways, and to bless their outgoings and incomings …"[109] Winslow was more prosaic when he reviewed the political situation with respect to surrounding natives in December 1621: "Wee have found the Indians very faithfull in their Covenant of Peace with us; very loving and readie to pleasure us …," not only the greatest, Massasoit, "but also all the Princes and peoples round about us" for fifty miles. Even a sachem from Martha's Vineyard, who they never saw, and also seven others came in to submit to King James "so that there is now great peace amongst the Indians themselves, which was not formerly, neither would have bin but for us …"[110]

"Thanksgiving"

Bradford wrote in his journal that come fall together with their harvest of Indian corn, they had abundant fish and fowl, including many turkeys they took in addition to venison. He affirmed that the reports of plenty that many report "to their friends in England" were not "feigned but true reports".[111] He did not, however, describe any harvest festival with their native allies. Winslow, however, did, and the letter which was included in Mourt's Relation became the basis for the tradition of "the first Thanksgiving".[lower-alpha 16]

Winslow's description of what was later celebrated as the first Thanksgiving was quite short. He wrote that after the harvest (of Indian corn, their planting of peas were not worth gathering and their barley harvest of barley was "indifferent"), Bradford sent out four men fowling "so we might after a more special manner rejoice together, after we had gathered the fruit of our labours …"[113] The time was one of recreation, including the shooting of arms, and many Natives joined them, including Massasoit and 90 of his men,[lower-alpha 17] who stayed three days. They killed five deer which they presented to Bradford, Standish and others in Plymouth. Winslow concluded his description by telling his readers that "we are so farre from want, that we often wish you partakers of our plentie."[115]

The Narragansett threat

The various treaties created a system where the English settlers filled the vacuum created by the epidemic. The villages and tribal networks surrounding Plymouth now saw themselves as tributaries to the English and (as they were assured) King James. The settlers also viewed the treaties as committing the Natives to a form of vassalage. Nathaniel Morton, Bradford's nephew, interpreted the original treaty with Massasoit, for example, as "at the same time" (not within the written treaty terms) acknowledging himeself "content to become the Subject of our Sovereign Lord the King aforesaid, His Heirs and Successors, and gave unto them all the Lands adjacent, to them and their Heirs for ever".[116] The problem with this political and commercial system was that it "incurred the resentment of the Narragansett by depriving them of tributaries just when Dutch traders were expanding their activities in the [Narragansett] bay".[117] In January 1622 the Narraganset responded by issuing an ultimatum to the English.

In December 1621 the Fortune (which had brought 35 more settlers) had departed for England.[lower-alpha 18] Not long afterwards rumors began to reach Plymouth that the Narragansett were making warlike preparations against the English.[lower-alpha 19] Winslow believed that that nation had learned that the new settlers brought neither arms nor provisions and thus in fact weakened the English colony.[121] Bradford saw their belligerency as a result of their desire to "lord it over" the peoples who had been weakened by the epidemic (and presumably obtain tribute from them) and the colonists were "a bar in their way".[122] In January 1621/22 a messenger from Narraganset sachem Canonicus (who travelled with Tokamahamon, Winslow's "special friend") arrived looking for Squanto, who was away from the settlement. Winslow wrote that the messenger appeared relieved and left a bundle of arrows wrapped in a rattlesnake skin. Rather than let him depart, however, Bradford committed him to the custody of Standish. The captain asked Winslow, who had a "speciall familiaritie" with other Indians, to see if he could get anything out of the messenger. The messenger would not be specific but said that he believed "they were enemies to us." That night Winslow and another (probably Hopkins) took charge of him. After his fear subsided, the messenger told him that the messenger who had come from Canonicus last summer to treat for peace, returned and persuaded the sachem on war. Canonicus was particularly aggrieved by the "meannesse" of the gifts sent him by the English, not only in relation to what he sent to colonists but also in light of his own greatness. On obtaining this information, Bradford ordered the messenger released.[123]

When Squanto returned he explained that the meaning of the arrows wrapped in snake skin was enmity; it was a challenge. After consultation, Bradford stuffed the snake skin with powder and shot and had a Native return it to Canonicus with a defiant message. Winslow wrote that the returned emblem so terrified Canonicus that he refused to touch it, and that it passed from hand to hand until, by a circuitous route, it was returned to Plymouth.[124]

Squanto's double dealing

Notwithstanding the colonists' bold response to the Narragansett challenge, the settlers realized their defenselessness to attack.[125] Bradford instituted a series of measures to secure Plymouth. Most important they decided to enclose the settlement within a pale (probably much like what was discovered surrounding Nenepashemet's fort). They shut the inhabitants within gates that were locked at night, and a night guard was posted. Standish divided the men into four squadrons and drilled them in where to report in the event of alarm. They also came up with a plan of how to respond to fire alarms so as to have a sufficient armed force to respond to possible Native treachery.[126] The fence around the settlement required the most effort since it required felling suitable large trees, digging holes deep enough to support the large timbers and securing them close enough to each other to prevent penetration by arrows. This work had to be done in the winter and at a time too when the settlers were on half rations because of the new and unexpected settlers.[127] The work took more than a month to complete.[128]

False alarms

By the beginning of March, the fortification of the settlement had been accomplished. It was now time when the settlers had promised the Massachuset they would come to trade for furs. They received another alarm however, this time from Hobomok, who was still living with them. Hobomok told of his fear that the Massachuset had joined in a confederacy with the Narraganset and if Standish and his men went there, they would be cut off and at the same time the Narraganset would attack the settlement at Plymouth. Hobomok also told them that Squanto was part of this conspiracy, that he learned this from other Natives he met in the woods and that the settlers would find this out when Squanto would urge the settlers into the Native houses "for their better advantage".[129] This allegation must have come as a shock to the English given that Squanto's conduct for nearly a year seemed to have aligned him perfectly with the English interest both in helping to pacify surrounding societies and in obtaining goods that could be used to reduce their debt to the settlers' financial sponsors. Bradford consulted with his advisors, and they concluded that they had to make the mission despite this information. The decision was made partly for strategic reasons. If the colonists cancelled the promised trip out of fear and instead stayed shut up "in our new-enclosed towne", they might encourage even more aggression. But the main reason they had to make the trip was that their "Store was almost emptie" and without the corn they could obtain by trading "we could not long subsist …"[130] The governor therefore deputed Standish and 10 men to make the trip and sent along both Squanto and Hobomok, given "the jealousy between them".[131]

Not long after the shallop departed, "an Indian belonging to Squanto's family" came running in. He betrayed signs of great fear, constantly looking behind him as if someone "were at his heels". He was taken to Bradford to whom he told that many of the Narraganset together with Corbitant "and he thought Massasoit" were about to attack Plymouth.[131] Winslow (who was not there but wrote closer to the time of the incident than did Bradford) gave even more graphic details: The Native's face was covered in fresh blood which he explained was a wound he received when he tried speaking up for the settlers. In this account he said that the combined forces were already at Nemasket and were set on taking advantage of the opportunity supplied by Standish's absence.[132] Bradford immediately put the settlement on military readiness and had the ordnance discharge three rounds in the hope that the shallop had not gone too far. Because of calm seas Standish and his men had just reached Gurnet's Nose, heard the alarm and quickly returned. When Hobomok first heard the news he "said flatly that it was false …" Not only was he assured of Massasoit's faithfulness, he knew that his being a pniese meant he would have been consulted by Massasoit before he undertook such a scheme. To make further sure Hobomok volunteered his wife to return to Pokanoket to assess the situation for herself. At the same time Bradford had the watch maintained all that night, but there were no signs of Natives, hostile or otherwise.[133]

Hobomok's wife found the village of Pokanoket quiet with no signs of war preparations. She then informed Massasoit of the commotion at Plymouth. The sachem was "much offended at the carriage of Tisquantum" but was grateful for Bradford's trust in him [Massasoit]. He also sent word back that he would send word to the governor, pursuant to the first article of the treaty they had entered, if any hostile actions were preparing.[134]

Allegations against Squanto

Winslow writes that "by degrees wee began to discover Tisquantum," but he does not describe the means or over what period of time this discovery took place. There apparently was no formal proceeding. The conclusion reached, according to Winslow, was that Squanto had been using his proximity and apparent influence over the English settlers "to make himselfe great in the eyes of" local Natives for his own benefit. Winslow explains that Squanto convinced locals that he had the ability to influence the English toward peace or war and that he frequently extorted Natives by claiming that the settlers were about to kill them in order "that thereby hee might get gifts to himself to work their peace …"[135]

Bradford's account agrees with Winslow's to this point, and he also explains where the information came from: "by the former passages, and other things of like nature",[136] evidently referring to rumors Hobomok said he heard in the woods. Winslow goes much further in his charge, however, claiming that Squanto intended to sabotage the peace with Massasoit by false claims of Massasoit aggression "hoping whilest things were hot in the heat of bloud, to provoke us to march into his Country against him, whereby he hoped to kindle such a flame as would not easily be quenched, and hoping if that blocke were once removed, there were no other betweene him and honour" which he preferred over life and peace.[137] Winslow later remembered "one notable (though) wicked practice of this Tisquantum"; namely, that he told the locals that the English possessed the "plague" buried under their storehouse and that they could unleash it at will. What he referred to was their cache of gunpowder.[lower-alpha 20]

Massasoit's demand for Squanto

Captain Standish and his men eventually did go to the Massachuset and returned with a "good store of Trade". On their return, they saw that Massasoit was there and he was displaying his anger against Squanto. Bradford did his best to appease him, and he eventually departed. No long afterward, however, he sent a messenger demanding that Squanto is put to death. Bradford responded that although Squanto "deserved to die both in respect of him [Massasoit] and us", but said that Squanto was too useful to the settlers because otherwise, he had no one to translate. Not long afterward, the same messenger returned, this time with "divers others", demanding Squanto. They argued that Squanto being a subject of Massasoit, was subject, pursuant to the first article of the Peace Treaty, to the sachem's demand, in effect, rendition. They further argued that if Bradford would not produce pursuant to the Treaty, Massasoit had sent many beavers' skins to induce his consent. Finally, if Bradford still would not release him to them, the messenger had brought Massasoit's own knife by which Bradford himself could cut off Squanto's head and hands to be returned with the messenger. Bradford avoided the question of Massasoit's right under the treaty[lower-alpha 21] but refused the beaver pelts saying that "It was not the manner of the English to sell men's lives at a price …" The governor called Squanto (who had promised not to flee), who denied the charges and ascribed them to Hobomok's desire for his downfall. He nonetheless offered to abide by Bradford's decision. Bradford was "ready to deliver him into the hands of his Executioners" but at that instance, a boat passed before the town in the harbor. Fearing that it might be the French, Bradford said he had to first identify the ship before dealing with the demand. The messenger and his companions, however, "mad with rage, and impatient at delay" left "in great heat".[140]

Squanto's final mission with the settlers

Arrival of the Sparrow

The ship the English saw pass before the town was not French, but rather a shallop from the Sparrow, a shipping vessel sponsored by Thomas Weston and one other of the Plymouth settlement's sponsors, which was plying the eastern fishing grounds.[141] This boat brought seven additional settlers but no provisions whatsoever "nor any hope of any".[142] In a letter they brought, Weston explained that the settlers were to set up a salt pan operation on one of the islands in the harbor for the private account of Weston. He asked the Plymouth colony, however, to house and feed these newcomers, provide them with seed stock and (ironically) salt, until he was able to send the salt pan to them.[143] The Plymouth settlers had spent the winter and spring on half rations in order to feed the settlers that had been sent nine months ago without provisions.[144] Now Weston was exhorting them to support new settlers who were not even sent to help the plantation.[145] He also announced that he would be sending another ship that would discharge more passengers before it would sail on to Virginia. He requested that the settlers entertain them in their houses so that they could go out and cut down timber to lade the ship quickly so as not to delay its departure.[146] Bradford found the whole business "but cold comfort to fill their hungry bellies".[147] Bradford was not exaggerating. Winslow described the dire straits. They now were without bread "the want whereof much abated the strength and the flesh of some, and swelled others".[148] Without hooks or seines or netting, they could not collect the bass in the rivers and cove, and without tackle and navigation rope, they could not fish for the abundant cod in the sea. Had it not been for shellfish which they could catch by hand, they would have perished.[149] But there was more, Weston also informed them that the London backers had decided to dissolve the venture. Weston urged the settlers to ratify the decision; only then might the London merchants send them further support, although what motivation they would then have he did not explain.[150] That boat also, evidently,[lower-alpha 22] contained alarming news from the South. John Huddleston, who was unknown to them but captained a fishing ship that had returned from Virginia to the Maine fishing grounds, advised his "good friends at Plymouth" of the massacre in the Jamestown settlements by the Powhatan in which he said 400 had been killed. He warned them: "Happy is he whom other men's harms doth make to beware."[154] This last communication Bradford decided to turn to their advantage. Sending a return for this kindness, they might also seek fish or other provisions from the fishermen. Winslow and a crew were selected to make the voyage to Maine, 150 miles away, to a place they had never been.[157] In Winslow's reckoning, he left at the end of May for Damariscove.[lower-alpha 23] Winslow found the fishermen more than sympathetic and they freely gave what they could. Even though this was not as much as Winslow hoped, it was enough to keep them going until the harvest.[162]

When Winslow returned, the threat they felt had to be addressed. The general anxiety aroused by Huddleston's letter was heightened by the increasingly hostile taunts they learned of. Surrounding villagers were "glorying in our weaknesse", and the English heard threats about how "easie it would be ere long to cut us off". Even Massasoit turned cool towards the English, and could not be counted on to tamp down this rising hostility. So they decided to build a fort on burying hill in town. And just as they did when building the palisade, the men had to cut down trees, haul them from the forest and up the hill and construct the fortified building, all with inadequate nutrition and at the neglect of dressing their crops.[163]

Weston's English settlers

They might have thought they reached the end of their problems, but in June 1622 the settlers saw two more vessels arrive, carrying 60 additional mouths to feed. These were the passengers that Weston had written would be unloaded from the vessel going on to Virginia. That vessel also carried more distressing news. Weston informed the governor that he was no longer a part of the company sponsoring the Plymouth settlement. The settlers he sent just now, and requested the Plymouth settlement to house and feed, were for his own enterprise. The "sixty lusty men" would not work for the benefit of Plymouth; in fact he had obtained a patent and as soon as they were ready they would settle an area in Massachusetts Bay. Other letters also were brought. The other venturers in London explained that they had bought out Weston, and everyone was better off without him. Weston, who saw the letter before it was sent, advised the settlers to break off from the remaining merchants, and as a sign of good faith delivered a quantity of bread and cod to them. (Although, as Bradford noted in the margin, he "left not his own men a bite of bread.") The arrivals also brought news that the Fortune had been taken by French pirates, and therefore all their past effort to export American cargo (valued at £500) would count for nothing. Finally Robert Cushman sent a letter advising that Weston's men "are no men for us; wherefore I prey you entertain them not"; he also advised the Plymouth Separatists not to trade with them or loan them anything except on strict collateral."I fear these people will hardly deal so well with the savages as they should. I pray you therefore signify to Squanto that they are a distinct body from us, and we have nothing to do with them, neither must be blamed for their faults, much less can warrant their fidelity." As much as all this vexed the governor, Bradford took in the men and fed and housed them as he did the others sent to him, even though Weston's men would compete with his colony for pelts and other Native trade.[164] But the words of Cushman would prove prophetic.

Weston's men, "stout knaves" in the words of Thomas Morton,[165] were roustabouts collected for adventure[166] and they scandalized the mostly strictly religious villagers of Plymouth. Worse, they stole the colony's corn, wandering into the fields and snatching the green ears for themselves.[167] When caught, they were "well whipped", but hunger drove them to steal "by night and day". The harvest again proved disappointing, so that it appeared that "famine must still ensue, the next year also" for lack of seed. And they could not even trade for staples because their supply of items the Natives sought had been exhausted.[168] Part of their cares were lessened when their coasters returned from scouting places in Weston's patent and took Weston's men (except for the sick, who remained) to the site they selected for settlement, called Wessagusset (now Weymouth). But not long after, even there they plagued Plymouth, who heard, from Natives once friendly with them, that Weston's settlers were stealing their corn and committing other abuses.[169] At the end of August a fortuitous event staved off another starving winter: the Discovery, bound for London, arrived from a coasting expedition from Virginia. The ship had a cargo of knives, beads and other items prized by Natives, but seeing the desperation of the colonists the captain drove a hard bargain: He required them to buy a large lot, charged them double their price and valued their beaver pelts at 3s. per pound, which he could sell at 20s. "Yet they were glad of the occasion and fain to buy at any price …"[170]

Trading expedition with Weston's men

The Charity returned from Virginia at the end of September–beginning of October. It proceeded on to England, leaving the Wessagusset settlers well provisioned. The Swan was left for their use as well.[171] It was not long after they learned that the Plymouth settlers had acquired a store of trading goods that they wrote Bradford proposing that they jointly undertake a trading expedition, they to supply the use of the Swan. They proposed equal division of the proceeds with payment for their share of the goods traded to await arrival of Weston. (Bradford assumed they had burned through their provisions.) Bradford agreed and proposed an expedition southward of the Cape.[172]

Winslow wrote that Squanto and Massasoit had "wrought" a peace (although he doesn't explain how this came about). With Squanto as guide, they might find the passage among the Monomoy Shoals to Nantucket Sound;[lower-alpha 24] Squanto had advised them he twice sailed through the shoals, once on an English and once on a French vessel.[174] The venture ran into problems from the start. When in Plymouth Richard Green, Weston's brother-in-law and temporary governor of the colony, died. After his burial and receiving directions to proceed from the succeeding governor of Wessagusset, Standish was appointed leader but twice the voyage was turned back by violent winds. On the second attempt, Standish fell ill. On his return Bradford himself took charge of the enterprise.[175] In November they set out. When they reached the shoals, Squanto piloted the vessel, but the master of the vessel did not trust the directions and bore up. Squanto directed him through a narrow passage, and they were able to harbor near Mamamoycke (now Chatham).

That night Bradford went ashore with a few others, Squanto acting as translator and facilitator. Not having seen any of these Englishmen before, the Natives were initially reluctant. But Squanto coaxed them and they provided a plentiful meal of venison and other victuals. They were reluctant to allow the English to see their homes, but when Bradford showed his intention to stay on shore, they invited him to their shelters, having first removed all their belongings. As long as the English stayed, the Natives would disappear "bag and baggage" whenever their possessions were seen. Eventually Squanto persuaded them to trade and as a result, the settlers obtained eight hogsheads of corn and beans. The villagers also told them that they had seen vessels "of good burthen" pass through the shoals. And so, with Squanto feeling confident, the English were prepared to make another attempt. But suddenly Squanto became ill and died.[176]

Squanto's death

The sickness seems to have greatly shaken Bradford, for they lingered there for several days before he died. Bradford described his death in some detail:

In this place Squanto fell sick of Indian fever, bleeding much at the nose (which the Indians take as a symptom of death) and within a few days died there; desiring the Governor to pray for him, that he might go to the Englishmen's God in Heaven; and bequeathed sundry of his things to English friends, as remembrances of his love; of whom they had a great loss.[177]

Without Squanto to pilot them, the English settlers decided against trying the shoals again and returned to Cape Cod Bay.[178]

The English Separatists were comforted by the fact that Squanto had become a Christian convert. William Wood writing a little more than a decade later explained why some of the Ninnimissinuok began recognizing the power of "the Englishmens God, as they call him": "because they could never yet have power by their conjurations to damnifie the English either in body or goods" and since the introduction of the new spirit "the times and seasons being much altered in seven or eight years, freer from lightning and thunder, and long droughts, suddaine and tempestuous dashes of rain, and lamentable cold Winters".[179]

Philbrick speculates that Squanto may have been poisoned by Massasoit. His bases for the claim are (i) that other Native Americans had engaged in assassinations during the 17th century; and (ii) that Massasoit's own son, the so-called King Philip, may have assassinated John Sassamon, an event that led to the bloody King Philip's War a half-century later. He suggests that the "peace" Winslow says was lately made between the two could have been a "rouse" but does not explain how Massasoit could have accomplished the feat on the very remote southeast end of Cape Cod, more than 85 miles distant from Pokanoket.[180]

Squanto is reputed to be buried in the village of Chatham Port.[lower-alpha 25]

Assessment, memorials, representations, and folklore

Historical assessment

Because almost all the historical records of Squanto were written by English Separatists and because most of that writing had the purpose to attract new settlers, give account of their actions to their financial sponsors or to justify themselves to co-religionists, they tended to relegate Squanto (or any other Native American) to the role of assistant to them in their activities. No real attempt was made to understand Squanto or Native culture, particularly religion. The closest that Bradford got in analyzing him was to say "that Squanto sought his own ends and played his own game, … to enrich himself". But in the end, he gave "sundry of his things to sundry of his English friends".[177]

Historians' assessment of Squanto depended on the extent they were willing to consider the possible biases or motivations of the writers. Earlier writers tended to take the colonists' statements at face value. Current writers, especially those familiar with ethnohistorical research, have given a more nuanced view of Squanto, among other Native Americans. As a result, the assessment of historians has run the gamut. Adams characterized him as "a notable illustration of the innate childishness of the Indian character".[182] By contrast, Shuffelton says he "in his own way, was quite as sophisticated as his English friends, and he was one of the most widely traveled men in the New England of his time, having visited Spain, England, and Newfoundland, as well as a large expanse of his own region."[183] Early Plymouth historian Judge John Davis, more than a half century before, also saw Squanto as a "child of nature", but was willing to grant him some usefulness to the enterprise: "With some aberrations, his conduct was generally irreproachable, and his useful services to the infant settlement, entitle him to grateful remembrance."[184] In the middle of the 20th century Adolf was much harder on the character of Squanto ("his attempt to aggrandize himself by playing the Whites and Indians against each other indicates an unsavory facet of his personality") but gave him more importance (without him "the founding and development of Plymouth would have been much more difficult, if not impossible.").[185] Most have followed the line that Baylies early took of acknowledging the alleged duplicity and also the significant contribution to the settlers' survival: "Although Squanto had discovered some traits of duplicity, yet his loss was justly deemed a public misfortune, as he had rendered the English much service."[186]

Memorials and landmarks

As for monuments and memorials, although many (as Willison put it) "clutter up the Pilgrim towns there is none to Squanto …"[187] The first settlers may have named after him the peninsula called Squantum once in Dorchester,[188] now in Quincy, during their first expedition there with Squanto as their guide.[189] Thomas Morton refers to a place called "Squanto's Chappell",[190] but this is probably another name for the peninsula.[191]

Literature and popular entertainment

Squanto rarely makes appearances in literature or popular entertainment. Of all the 19th century New England poets and story tellers who drew on pre-Revolution America for their characters, only one seems to have mentioned Squanto. And while Henry Wadsworth Longfellow himself had five ancestors aboard the Mayflower, "The Courtship of Miles Standish" has the captain blustering at the beginning, daring the savages to attack, yet the enemies he addresses could not have been known to him by name until their peaceful intentions had already been made known:

Let them come if they like, be it sagamore, sachem, or pow-wow,

Aspinet, Samoset, Corbitant, Squanto, or Tokamahamon!

Squanto is almost equally scarce in popular entertainment, but when he appeared it was typically in implausible fantasies. Very early in what Willison calls the "Pilgrim Apotheosis", marked by the 1793 sermon of Reverend Chandler Robbins, in which he described the Mayflower settlers as "pilgrims",[192] a "Melo Drama" was advertised in Boston titled "The Pilgrims, Or the Landing of the Forefathrs at Plymouth Rock" filled with Indian threats and comic scenes. In Act II Samoset carries off the maiden Juliana and Winslow for a sacrifice, but the next scene presents "A dreadful Combat with Clubs and Shileds, between Samoset and Squanto".[193] Nearly two centuries later Squanto appears again as an action figure in the Disney film Squanto: A Warrior's Tale (1994) with not much more fidelity to history. Squanto (voiced by Frank Welker) appears in the first episode ("The Mayflower Voyagers", aired October 21, 1988) of the animated mini-series This Is America, Charlie Brown. A more historically accurate depiction of Squanto (as played by Kalani Queypo) appeared in the National Geographic Channel film Saints & Strangers, written by Eric Overmyer and Seth Fisher, which aired the week of Thanksgiving 2015.[194]

Didactic literature and folklore

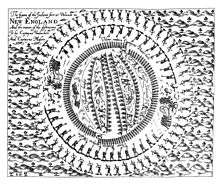

_(14768269922).jpg)

Where Squanto is most encountered is in literature designed to instruct children and young people, provide inspiration, or guide them to a patriotic or religious truth. This came about for two reasons. First, Lincoln's establishment of Thanksgiving as a national holiday enshrined the New England Anglo-Saxon festival, vaguely associated with an American strain of Protestantism, as something of a national origins myth, in the middle of a divisive Civil War when even some Unionists were becoming concerned with rising non-Anglo-Saxon immigration.[195] This coincided, as Ceci noted, with the "noble savage" movement, which was "rooted in romantic reconstructions of Indians (for example, Hiawatha) as uncorrupted natural beings—who were becoming extinct—in contrast to rising industrial and urban mobs". She points to the Indian Head coin first struck in 1859 "to commemorate their passing.'"[196] Even though there was only the briefest mention of "Thanksgiving" in the Plymouth settlers' writings, and despite the fact that he was not mentioned as being present (although, living with the settlers, he likely was), Squanto was the focus around both myths could be wrapped. He is, or at least a fictionalized portrayal of him, thus a favorite of a certain politically conservative American Protestant groups.[lower-alpha 26]

The story of the selfless "noble savage" who patiently guided and occasionally saved the "Pilgrims" (to whom he was subservient and who attributed their good fortune solely to their faith, all celebrated during a bounteous festival) was thought to be an enchanting figure for children and young adults. Beginning early in the 20th century Squanto entered high school textbooks,[lower-alpha 27] children's read-aloud and self-reading books,[lower-alpha 28] more recently learn-to-read and coloring books[lower-alpha 29] and children's religious inspiration books.[lower-alpha 30] Over time and particularly depending on the didactic purpose, these books have greatly fictionalized what little historical evidence remains of Squanto's life. Their portraits of Squanto's life and times spans the gamut of accuracy. Those intending to teach a moral lesson or tell history from a religious viewpoint tend to be the least accurate even when they claim to be telling a true historical story.[lower-alpha 31] Recently there have been attempts to tell the story as accurately as possible, without reducing Squanto to a mere servant of the English.[lower-alpha 32] There have even been attempts to place the story in the social and historical context of fur trade, epidemics and land disputes.[197] Almost none, however, have dealt with Squanto's life after "Thanksgiving" (except occasionally the story of the rescue of John Billington). An exception to all of that is the publication of a "young adult" version of Philbrick's best-selling adult history.[198] Nevertheless, given the sources which can be drawn on, Squanto's story inevitably is seen from the European perspective.

Notes, references and sources

Notes

- Kinnicutt proposes meanings for the various renderings of his name: Squantam, a contracted form of Musquqntum meaning "He is angry"; Tantum is a shortened form of Keilhtannittoom, meaning "My great god"; Tanto, from Kehtanito, for "He is the greatest god": and Tisquqntum, for Atsquqntum, possibly for "He possesses the god of evil."[5]

- Dockstader writes that Tiquantum means "door" or "entrance", although his source is not explained.[6]

- The languages of Southern New England are known today as Western Abenaki, Massachusett, Loup A and Loup B, Narragansett, Mohegan-Pequot, and Quiripi-Unquachog.[12] Many 17th-century writers state that numerous people in the coastal areas of Southern New England were fluent in two or more of these languages.[13]

- Roger Williams writes in his grammar of the Narragansett language that "their Dialects doe exceedingly differ" between the French settlements in Canada and the Dutch settlements in New York, "but (within that compass) a man may, by this helpe, converse with thousands of Natives all over the Countrey."[14]

- Adolf,[15]

- Winslow called this supernatural being Hobbamock (the Indians north of the Pokanokets call it Hobbamoqui, he said) and expressly equated him with the devil.[27] William Wood called this same supernatural being Abamacho and said that it presided over the infernal regions where "loose livers" were condemned to dwell after death.[28] Winslow used the term powah to refer to the shaman who conducted the healing ceremony,[29] and Wood described these ceremonies in detail.[30]

- Paleopathological evidence exists for European importation of typhoid, diphtheria, influenza, measles, chicken pox, whooping cough, tuberculosis, yellow fever, scarlet fever, gonorrhea and smallpox.[34]

- The Indians taken by Weymouth were Eastern Abenaki from Maine, whereas Squanto was Patuxet, a Southern New England Algonquin. He lived in Plymouth, where the Archangel neither reached nor planned to.

- See, e.g., Salisbury 1982, pp. 265–66 n.15; Shuffelton 1976, p. 109; Adolf 1964, p. 247; Adams 1892, p. 24 n. 2; Deane 1885, p. 37; Kinnicutt 1914, pp. 109–11

- See Philbrick 2006, pp. 95–96

- Mourt's Relation says that they left on June 10, but Prince points out that it was a Sabbath and therefore unlikely to be the day of their departure.[78] Both he and Young[79] follow Bradford, who recorded that they left on July 2.[80]

- "we promised him restitution, & desired him either to come Patuxet for satisfaction, or else we would bring them so much corne againe, he promised to come, wee used him very kindly for the present."[86]

- Bradford describes him as "a proper lusty man, and a man of account for his valour and parts amongst the Indians".[93]

- The Abeneki were known as "Tarrateens" or "Tarrenteens" and lived on the Kennebec and nearby rivers in Maine. "There was great enmity between the Tarrentines and the Alberginians, or the Indians of Massachusetts Bay."[104]

- Bradford quoted Deuteronomy 32:8, which those familiar would understand the unspoken allusion to a "waste howling wilderness." But the chapter also has the assurance that the Lord kept Jacob "as the apple of his eye."

- So Alexander Young put it as early as 1841.[112]

- Humins surmises that the entourage included sachems and other headmen of the confederation's villages."[114]

- According to John Smith's account in New England Trials (1622), the Fortune arrived at New Plymouth on November 11, 1621 o.s. and departed December 12.[118] Bradford described the 35 that were to remain as "unexpected or looked for" and detailed how they were less prepared than the original settlers had been, bringing no provisions, no material to construct habitation and only the poorest of clothes. It was only when they entered Cape Cod Bay, according to Bradford, that they began to consider what desperation they would be in if the original colonists had perished. The Fortune also brought a letter from London financier Thomas Weston complaining about holding the Mayflower for so long the previous year and failing to lade her for her return. Bradford's response was surprisingly mild. They also shipped back three hogshead of furs as well as sasssafras, and clapboard for a total freight value of £500.[119]

- Winslow wrote that the Narragansett had sought and obtained a peace agreement with the Plymouth settlers the previous summer,[120] although no mention of it is made in any of the writings of the settlers.

- The story was revealed by Squanto himself when some barrels of gunpowder were unearthed under a house. Hobomok asked what they were, and Squanto replied that it was the plague that he had told him and others about. Oddly in a tale of the wickedness of Squanto for claiming the English had control over the plague is this addendum: Hobomok asked one of the settlers whether it was true, and the settler replied, "no; But the God of the English had it in store, and could send it at is pleasure to the destruction of his and our enemies."[138]

- The first two numbered items of the treaty as it was printed in Mourt's Relation provided: "1. That neither he nor any of his should injure or doe hurt to any of our people. 2. And if any of his did hurt to any of ours, he should send the offender, that we might punish him."[139] As printed the terms do not seem reciprocal, but Massasoit apparently thought they were. Neither Bradford in his answer to the messenger, nor Bradford or Winslow in their history of this event denies that the treaty entitled Massasoit to the return of Squanto.

- The events in Bradford's and Winslow's chronologies, or at least the ordering of the narratives, do not agree. Bradford's order is: (1) Provisions spent, no source of food found; (2) end of May brings shallop from Sparrow with Weston letters and seven new settlers; (3) Charity and Swan arrive depositing "sixty lusty men"'; (4) amidst "their straights" letter from Huddleston brought by "this boat" from the east; (5) Winslow and men return with them; (6) "this summer" they build fort.[151] Winslow's sequence is: (1) Shallop from Sparrow arrives; (2) end of May 1622, food storehouse spent; (3) Winslow and his men sail to Damariscove in Maine; (4) on return finds state of colony much weakened from lack of bread; (5) Native taunts cause settlers to start building fort, at expense of planting; (6) end of June–beginning of July Charity and Swan arrive.[152] The chronology adopted below follows Willison's combination of the two accounts.[153] Although Bradford's rather careless use of pronouns makes it unclear which "pilot" Winslow followed to the fishing grounds in Maine (which carried the Huddleton letter) or indeed who brought the Huddleton letter,[154] it is likely the shallop from the Sparrow and not another boat from Huddleston himself, as Willison and Adams before him[155] conclude. Philbrick has Huddleston's letter arrive after the Charity and Swan, and only mentions Winslow's voyage to the fishing grounds, which, if it took place after the arrival of those two vessels, would have taken place after the end of the fishing season.[156]

- The islands off the Damariscove river in Maine early on provided stages for fishermen from early times.[158] Damariscove Island was called Damerill's Isles on John Smith's 1614 map. Bradford noted that in 1622 there "were many more ships come afishing".[159] The Sparrow was stationed on these grounds.[160] Morison states that 300 to 400 sails of different countries, including 30 to 40 English as well as some from Virginia, came to fish these grounds in May, leaving in the summer.[161] Winslow's mission was to beg or borrow supplies from these fishermen.

- These were the same "perilous shoals and breakers" that caused the Mayflower to turn back on November 9, 1620 o.s.[173]

- A marker on the front lawn of the Nickerson Genealogical Research Center on Orleans Road in Chatham states that Squanto is buried at the head of Ryder's Cove. Nickerson claims that the skeleton which washed out "of a hill between Head of the Bay and Cove's Pond" around 1770 was probably Squanto's.[181]

- See, for example, "The Story of Squanto". Christian Worldview Journal. August 26, 2009. Archived from the original on December 8, 2013.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link); "Squanto: A Thanksgiving Drama". Focus on the Family Daily Broadcast. May 1, 2007.; "Tell Your Kids the Story of Squanto". Christian Headlines. November 19, 2014.; "History of Thanksgiving Indian: Why Squanto already knew English". Bill Petro: Building the Gap from Strategy and Execution. November 23, 2016..

- The illustration at the head of this article, for example, is one of two of Squanto in Bricker, Garland Armor (1911). The Teaching of Agriculture in the High School. New York: Macmillan Co. (Plates after p. 112.)

- For example, Olcott, Frances Jenkins (1922). Good Stories for Great Birthdays, Arranged for Story-Telling and Reading Aloud and for the Children's Own Reading. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co. This book was reissued by the University of Virginia Library in 1995. Squanto is referred to as "Tisquantum" and "A Big Indian" in the stories entitled "The Father of the New England Colonies" (William Bradford), at pp. 125–139. See also Bradstreet, Howard (1925). Squanto. [Hartford? Conn.]: [Bradstreet?].

- E.g.: Beals, Frank L.; Ballard, Lowell C. (1954). Real Adventure with the Pilgrim Settlers: William Bradford, Miles Standish, Squanto, Roger Williams. San Francisco: H. Wagner Publishing Co. Bulla, Clyde Robert (1954). Squanto, Friend of the White Men. New York: T.Y. Crowell. Bulla, Clyde Robert (1956). John Billington, friend of Squanto. New York: Crowell. Stevenson, Augusta; Goldstein, Nathan (1962). Squanto, Young Indian Hunter. Indianapolis, Indiana: Bobbs-Merrill. Anderson, A.M. (1962). Squanto and the Pilgrims. Chicago: Wheeler. Ziner, Feenie (1965). Dark Pilgrim. Philadelphia: Chilton Books. Graff, Robert; Graff (1965). Squanto: Indian Adventurer. Champaign, Illinois: Garrard Publishing Co. Grant, Matthew G. (1974). Squanto: The Indian who Saved the Pilgrims. Chicago: Creative Education. Jassem, Kate (1979). Squanto: The Pilgrim Adventure. Mahwah, New Jersey: Troll Associates. Cole, Joan Wade; Newsom, Tom (1979). Squanto. Oklahoma City, Oklahoma: Economy Co. ;Kessel, Joyce K. (1983). Squanto and the First Thanksgiving. Minneapolis, Minnesota: Carolrhoda Bookr. Rothaus, James R. (1988). Squanto: The Indian who Saved the Pilgrims (1500 -1622). Mankato, Minnesota: Creative Education.;Celsi, Teresa Noel (1992). Squanto and the First Thanksgiving. Austin, Texas: Raintree Steck-Vaughn. Dubowski, Cathy East (1997). The Story of Squanto: First Friend to the P. Milwaukee, Wisconsin: Gareth Stevens Publishers. ;Bruchac, Joseph (2000). Squanto's Journey: The Story of the First Thanksgiving. n.l.: Silver Whistle.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) Samoset and Squanto. Peterborough, New Hampshire: Cobblestone Publishing Co. 2001. Whitehurst, Susan (2002). A Plymouth Partnership: Pilgrims and Native Americans. New York: PowerKids Press. Buckley, Susan Washborn (2003). Squanto the Pilgrims' Friend. New York: Scholastic. Hirschfelder, Arlene B. (2004). Squanto, 1585?-1622. Mankato, Minnesota: Blue Earth Books. Roop, Peter; Roop, Connie (2005). Thank You, Squanto!. New York: Scholastic. Banks, Joan (2006). Squanto. Chicago: Wright Group / McGraw Hill. Ghiglieri, Carol; Noll, Cheryl Kirk (2007). Squanto: A Friend to the Pilgrims. New York: Scholastic.

- E.g., Hobbs, Carolyn; Roland, Pat (1981). Squanto. Milton, Florida: Printed by the Children's Bible Club. The Legend of Squanto. Carol Stream, Illinois. 2005. Metaxas, Eric (2005). Squanto and the First Thanksgiving. Rowayton, Connecticut: ABDO Publishing Co.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) The book was retitled Squanto and the Miracle of Thanksgiving when it was republished in 2014 by the religious publisher Thomas Nelson. The book was turned into an animated video by Rabbit Ears Entertainment in 2007.

- For example, Metaxas 2005, praised as a "true story" by the author's colleague Chuck Colson, misstates almost every well documented fact in Squanto's life. It begins with the abduction of 12 year old Squanto which the first sentence dates at "the year of our Lord 1608" (rather than 1614). When he meets the "Pilgrims" he greets Governor Bradford (rather than Carver). The rest is A fictIonalized religious parable which ends with Squanto (after "Thanksgiving" and before any allegations of treachery) thanking God for the Pilgrims.

- Bruchac 2000, for example, even names Hunt, Smith and Dermer and tries to portray Squanto from a Native American, rather than "Pilgrim," perspective.

References

- Baxter 1890, p. I104 n.146; Kinnicutt 1914, pp. 110–12.

- Young 1841, p. 202 n.1.

- Mann 2005.

- Martin 1978, p. 34.

- Kinnicutt 1914, p. 112.

- Dockstader 1977, p. 278.

- Salisbury 1981, p. 230.

- Salisbury 1981, pp. 228.

- Salisbury 1981, pp. 228–29.

- Bragdon 1996, p. i.

- Letter of Emmanuel Altham to his brother Sir Edward Altham, September 1623, in James 1963, p. 29. A copy of the letter is also reproduced online by MayflowerHistory.com.

- Goddard 1978, pp. passim.

- Bragdon 1996, pp. 28–29, 34.

- Williams 1643, pp. [ii]–[iii]. See also Salisbury 1981, p. 229.

- Adolf 1964, p. 257 n.1.

- Bradford 1952, p. 82 n.7.

- Bennett 1955, pp. 370–71.

- Bennett 1955, pp. 374–75.

- Russell 1980, pp. 120–21; Jennings 1976, pp. 65–67.

- Jennings 1976, p. 112.

- Winslow 1924, p. 57 reprinted at Youmg 1841, p. 361

- Bragdon 1996, p. 146.