Pigs in culture

Pigs, widespread in societies around the world since neolithic times, have been used for many purposes in art, literature, and other expressions of human culture. In classical times, the Romans considered pork the finest of meats, enjoying sausages, and depicting them in their art. Across Europe, pigs have been celebrated in carnivals since the Middle Ages, becoming specially important in Medieval Germany in cities such as Nuremberg, and in Early Modern Italy in cities such as Bologna.

In literature, both for children and adults, pig characters appear in allegories, comic stories, and serious novels. In art, pigs have been represented in a wide range of media and styles from the earliest times in many cultures. Pig names are used in idioms and animal epithets, often derogatory, since pigs have long been linked with dirtiness and greed, while places such as Swindon are named for their association with swine. The eating of pork is forbidden in Islam and Judaism, but pigs are sacred in some other religions.

Celebration of meat

Classical times

The scholar Michael MacKinnon writes that "Pork was generally considered the choicest of all the domestic meats consumed during Roman times, and it was ingested in a multitude of forms, from sausages to steaks, by rich and poor alike. No other animal had so many Latin names (e.g. sus, porcus, porco, aper) or was the ingredient in so many ancient recipes as outlined in the culinary manual of Apicius."[1] Pigs have been found at almost every archaeological site in Roman Italy; they are described by Roman agricultural writers such as Cato and Varro, and in Pliny the Elder's Natural History. MacKinnon notes that ancient breeds of pig can be seen on monuments such as the Arch of Constantine, which portrays a lop-eared, fat-bellied, and smooth breed.[1]

Carnival

Benton Jay Komins, a scholar of culture, notes that the pig has been celebrated throughout Europe since ancient times in its carnivals, the name coming from the Italian carne levare, the lifting of meat.[2] Komins quotes the scholars Peter Stallybrass and Allon White on the pig's ambiguous role:[2]

"In the fair and the carnival, we would expect to find a quite different orientation toward the pig: in 'carne-levare' the pig was celebrated; the pleasures of food were represented in the sausage and the rites of inversion were emblematized in the pig's bladder of the fool. ... Even in the carnival the pig was the locus of conflicting meanings. If the pig was duly celebrated, it could also become the symbolic analogy of scapegoated groups and demonized 'Others'".[3]

English tradition

In England, pork pies were being made in Melton Mowbray, Leicestershire by the 1780s, according to the Melton Mowbray Pork Pie Association (founded in 1998). The pies were originally baked in a clay pot with a pastry cover, developing to their modern form of a pastry case. Local tradition states that farm hands carried these while at work; aristocratic fox hunters of the Quorn, Cottesmore and Belvoir hunts supposedly saw this and acquired a taste for the pies.[4][5] A slightly later date of origin is given by the claim that pie manufacture in the town began around 1831 when a local baker and confectioner, Edward Adcock, started to make pies as a sideline.[6] Melton Mowbray pork pies were granted PGI status in 2008.[7]

German tradition

German cities such as Nuremberg have made pork sausages since at least 1315 AD, when the Würstlein (sausage controller) office was introduced. Some 1500 types of sausage are produced in the country. The Nuremberg bratwurst is required to be at most 90 millimetres (3.5 in) long and to weigh at most 25 grams (0.88 oz); it is flavoured with mace, pepper, and marjoram. In Early Modern times starting in 1614, Nuremberg's butchers paraded through the city each year carrying a 400 metres (440 yd) long sausage.[8]

A range of Bratwurst grilled sausages at the main market in Nuremberg

A range of Bratwurst grilled sausages at the main market in Nuremberg

Italian tradition

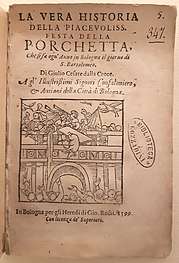

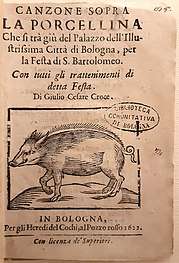

The pig, and pork products such as mortadella, were economically important in Italian cities such as Bologna and Modena in the Early Modern period, and celebrated as such; they have remained so into modern times. In 2019, the Istituzione Biblioteche Bologna held an exhibition Pane e salame. Immagini gastronomiche bolognesi dalle raccolte dell'Archiginnasio ("Bread and salami. Bolognese gastronomic images from the Archiginnasio collection") on the gastronomic images in its collection.[9][10]

La Vera Historia della Piacevolissima Festa Della Porchetta ("The True History of the Most Pleasant Feast of the Little Pig") by Giulio Cesare Croce, Bologna, 1599

La Vera Historia della Piacevolissima Festa Della Porchetta ("The True History of the Most Pleasant Feast of the Little Pig") by Giulio Cesare Croce, Bologna, 1599 Canzone Sopra La Porcellina ("Song Upon the Piglet") by Giulio Cesare Croce, Bologna, 1622

Canzone Sopra La Porcellina ("Song Upon the Piglet") by Giulio Cesare Croce, Bologna, 1622 Dichiarazione del Bando delle Mortadelle ("Declaration of the Band of the Mortadellas"), Bologna, 1661

Dichiarazione del Bando delle Mortadelle ("Declaration of the Band of the Mortadellas"), Bologna, 1661 Gli Elogi del Porco ("The Praises of the Pig"), Modena, 1761

Gli Elogi del Porco ("The Praises of the Pig"), Modena, 1761 Hams, pigs' trotters, sausages, and mortadella in Bologna, 2019

Hams, pigs' trotters, sausages, and mortadella in Bologna, 2019

Literature

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Pigs |

For adults

Pigs have been brought into literature for varying reasons, ranging from the pleasures of eating, as in Charles Lamb's A Dissertation upon Roast Pig, to William Golding's Lord of the Flies (with the fat character "Piggy"), where the rotting boar's head on a stick represents Beelzebub, "lord of the flies" being the direct translation of the Hebrew בעל זבוב, and George Orwell's allegorical novel Animal Farm, where the central characters, representing Soviet leaders, are all pigs.[2][11][12][13] The pig is used to comic effect in P. G. Wodehouse's stories set in Blandings Castle, where the eccentric Lord Emsworth keeps an extremely fat prize pig called the Empress of Blandings which is frequently stolen, kidnapped or otherwise threatened.[11][14] Quite a different use is made of the pig in Lloyd Alexander's fantasy books The Chronicles of Prydain, where Hen Wen is a pig with foresight, used to see the future and locate mystical items such as The Black Cauldron.[15]

One of the earliest literary references is Heraclitus, who speaks of the preference pigs have for mud over clean water in the Fragments.[16] In Wu Cheng'en's 16th century Chinese novel Journey to the West, Zhu Bajie is part human, part pig.[17] In books, poems and cartoons in 18th century England, The Learned Pig was a trained animal who appeared to be able to answer questions.[18] Thomas Hardy describes the killing of a pig in his 1895 novel Jude the Obscure.[19]

For children

Pigs have featured in children's books since at least 1840, when Three Little Pigs appeared in print;[20] the story has appeared in many different versions such as Disney's 1933 film and Roald Dahl's 1982 Revolting Rhymes. Even earlier is the popular 18th-century English nursery rhyme and fingerplay, "This Little Piggy",[21] frequently in film and literature, such as the Warner Brothers cartoons A Tale of Two Kitties (1942) and A Hare Grows In Manhattan (1947) which use the rhyme to comic effect. Two of Beatrix Potter's "little books", The Tale of Pigling Bland (1913) and The Tale of Little Pig Robinson (1930), feature the adventures of pigs dressed as people.[11]

Several animated cartoon series have included pigs as prominent characters. One of the earliest pigs in cartoon was the gluttonous "Piggy", who appeared in four Warner Brothers Merrie Melodies shorts between 1931 and 1937, most notably Pigs Is Pigs, and was followed by Porky Pig, with similar habits.[22]

Piglet is Pooh's constant companion in A. A. Milne's Winnie the Pooh stories and the Disney films based on them, while in Charlotte's Web, the central character Wilbur is a pig who formed a relationship with a spider named Charlotte.[23] The 1995 film Babe humorously portrayed a pig who wanted to be a herding dog, based on the character in Dick King-Smith's 1983 novel The Sheep Pig.[24] Among new takes on the classic Three Little Pigs is Corey Rosen Schwartz and Dan Santat's 2012 The Three Ninja Pigs.[25]

Art

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pigs in art. |

Pigs have appeared in art in media including pottery, sculpture, metalwork, engravings, oil paintings, watercolour, and stained glass, from neolithic times onwards. Some have functioned as amulets.[26]

.jpg) Neolithic pottery pig, Hemudu culture, Zhejiang, China

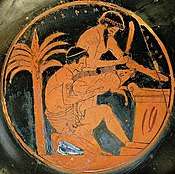

Neolithic pottery pig, Hemudu culture, Zhejiang, China Two men sacrificing a pig to Demeter. red-figure pot, Ancient Greece

Two men sacrificing a pig to Demeter. red-figure pot, Ancient Greece Sarcophagus with Calydonian Boar hunt. Athens, 2nd century

Sarcophagus with Calydonian Boar hunt. Athens, 2nd century Boar-helmeted figure on the Gundestrup Cauldron. 3rd century

Boar-helmeted figure on the Gundestrup Cauldron. 3rd century

Wild boar with boarhounds. Silver powder flask, Germany, 16th century

Wild boar with boarhounds. Silver powder flask, Germany, 16th century The Hog. Etching by Rembrandt van Rijn, 1643

The Hog. Etching by Rembrandt van Rijn, 1643 The Slaughtered Pig by Barent Fabritius, 1656

The Slaughtered Pig by Barent Fabritius, 1656 Pig market in a Dutch town by Nicolaes Molenaer, 17th century

Pig market in a Dutch town by Nicolaes Molenaer, 17th century Pig at the feet of St Anthony the Hermit. Stained glass, Chapelle Notre-Dame-de-Lhor, Moselle, France

Pig at the feet of St Anthony the Hermit. Stained glass, Chapelle Notre-Dame-de-Lhor, Moselle, France.jpg) Prince Hunting Wild Boar. Gouache and gold on paper. India, c. 1765

Prince Hunting Wild Boar. Gouache and gold on paper. India, c. 1765_by_Mori_Sosen.jpg) Folding screens of Inoshishi-zu by Mori Sosen. Edo period, Japan, 18th-19th century

Folding screens of Inoshishi-zu by Mori Sosen. Edo period, Japan, 18th-19th century

Ritual pig mask, Sepik region, Papua New Guinea. Rattan, palm leaf sheaths, and cassowary feathers. Collected 1914

Ritual pig mask, Sepik region, Papua New Guinea. Rattan, palm leaf sheaths, and cassowary feathers. Collected 1914 Amulet in shape of a pig. Pottery, Mexico

Amulet in shape of a pig. Pottery, Mexico

Religion

The pig has come to be seen as unacceptable to some world religions. In Islam and Judaism the consumption of pork is forbidden.[27][28] Many Hindus are lacto-vegetarian, avoiding all kinds of meat.[29] In Buddhism, the pig symbolises delusion (Sanskrit: moha), one of the three poisons (Sanskrit: triviṣa).[30] As with Hindus, many Buddhists are vegetarian, and some sutras of the Buddha state that meat should not be eaten;[31] monks in the Mahayana traditions are forbidden to eat meat of any kind.[32]

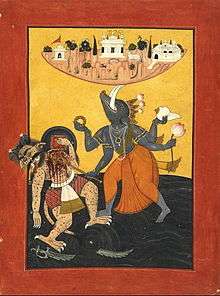

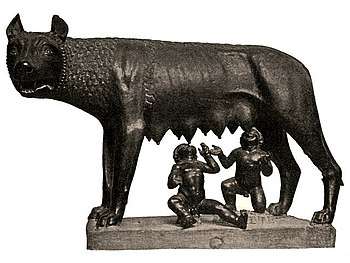

Pigs have in contrast been sacred in several religions, including the Druids of Ireland, whose priests were called "swine". One of the animals sacred to the Roman goddess Diana was the boar; she sent the Calydonian boar to destroy the land. In Hinduism, the boar-headed Varaha is venerated as an avatar of the god Vishnu.[33] The sow was sacred to the Egyptian goddess Isis and used in sacrifice to Osiris.[34]

Places

Many places are named for pigs. In England such placenames include Grizedale ("Pig valley", from Old Scandinavian griss, young pig, and dalr, valley), Swilland ("Pig land", from Old English swin and land), Swindon ("Pig hill"), and Swineford ("Pig ford").[35] In Scandinavia there are names such as Svinbergen ("Pig hill"), Svindal ("Pig valley"), Svingrund ("Pig ground"), Svinhagen ("Pig hedge"), Svinkärr ("Pig marsh"), Svinvik ("Pig bay"), Svinholm ("Pig islet"), Svinskär ("Pig skerry"), Svintorget ("Pig market"), and Svinö ("Pig island").[36]

Idiom

Several idioms related to pigs have entered the English language, often with negative connotations of dirt, greed, or the monopolisation of resources, as in "road hog" or "server hog". As the scholar Richard Horwitz puts it, people all over the world have made pigs stand for "extremes of human joy or fear, celebration, ridicule, and repulsion".[37] Pig names are used as epithets for negative human attributes, especially greed, gluttony, and uncleanliness, and these ascribed attributes have often led to critical comparisons between pigs and humans.[38] "Pig" is used as a slang term for either a police officer or a male chauvinist, the latter term adopted originally by the women's liberation movement in the 1960s.[39]

See also

References

- MacKinnon, Michael (2001). "High on the Hog: Linking Zooarchaeological, Literary, and Artistic Data for Pig Breeds in Roman Italy". American Journal of Archaeology. 105 (4): 649–673. doi:10.2307/507411. ISSN 0002-9114. JSTOR 507411.

- Komins, Benton Jay (2001). "Western Culture and the Ambiguous Legacies of the Pig". CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture. 3 (4). doi:10.7771/1481-4374.1137. ISSN 1481-4374.

- Stallybrass, Peter; White, Allon (1986). The Politics and Poetics of Transgression. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0416415803. Cited by Komins (2001)

- "History of Melton Mowbray Pork Pie". Melton Mowbray Pork Pie Association. Archived from the original on 2 May 2015. Retrieved 15 April 2015.

- Wilson, C. Anne (June 2003). Food and Drink in Britain: From the Stone Age to the 19th Century. Academy Chicago Publishers. p. 273. ISBN 978-0897333641.

- Brownlow, J. E. (1963). "The Melton Mowbray Pork-Pie Industry". Transactions of the Leicestershire Archaeological and Historical Society. 37: 36.

- "Pork pie makers celebrate status". BBC News. 4 April 2008.

- Newey, Adam (8 December 2014). "Nuremberg, Germany: celebrating the city's sausage". The Daily Telegraph.

- "Eventi: Pane e salame" (in Italian). Istituzione Biblioteche Bologna. Retrieved 31 December 2019.

- Virbila, S. Irene (7 August 1988). "Fare of the Country; Mortadella: Bologna's Bologna". The New York Times.

- Mullan, John (21 August 2010). "Ten of the best pigs in literature". The Guardian.

- Bragg, Melvyn. "Topics - Pigs in literature". BBC Radio 4. Retrieved 1 January 2020.

Animal Farm ... Sir Gawain and the Green Knight ... The Mabinogion ... The Odyssey ... (In Our Time)

- Sillar, Frederick Cameron (1961). The symbolic pig: An anthology of pigs in literature and art. Oliver & Boyd. OCLC 1068340205.

- "Blandings". BBC. Retrieved 31 December 2019.

- Jones, Mary (2003). "Hen Wen". Ancient Texts.

- Heraclitus, Fragment 37

- "Zhu Bajie, Zhu Wuneng". Nations Online. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- Buzwell, Greg (19 August 2016). "William Shakespeare and The Learned Pig". British Library.

- Yallop, Jacqueline (15 July 2017). "Pig tales – the swine in books and art". The Guardian.

- Robinson, Robert D. (March 1968). "The Three Little Pigs: From Six Directions". Elementary English. 45 (3): 356–359. JSTOR 41386323.

- Herman, D. (2007). The Cambridge Companion to Narrative. Cambridge University Press. p. 9. ISBN 978-0521673662.

- CNN.com - TV Guide's 50 greatest cartoon characters of all time - July 30, 2002 Archived 23 December 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- Gagnon, Laurence (1973). "Webs of Concern: The Little Prince and Charlotte's Web". Children's Literature. 2 (2): 61–66. doi:10.1353/chl.0.0419.

- Chanko, Kenneth M. (18 August 1995). "This Pig Just Might Fly | Movies". Entertainment Weekly.

- "Variations on Favorite Stories: The Three Little Pigs". ROD Library, University of Northern Iowa. Archived from the original on 10 May 2020. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- "Pig". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 2 January 2020.

- Qur'an 2:173, 5:3, 6:145, and 16:115.

- Leviticus 11:3–8

- Insel, Paul (2014). Nutrition. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 231. ISBN 978-1-284-02116-5. OCLC 812791756.

- Loy, David (2003). The Great Awakening: A Buddhist Social Theory. Simon and Schuster. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-86171-366-0.

- Sutras on refraining from eating meat

- "Buddhism & Vegetarianism". 21 October 2013. Archived from the original on 21 October 2013. Cite magazine requires

|magazine=(help) - Dalal, Roshen (2011). Hinduism: An Alphabetical Guide. Penguin Books India. pp. 444–445. ISBN 978-0-14-341421-6.

- Bonwick, James (1894). "Sacred Pigs". Library Ireland.

- Mills, A. D. (1993). A Dictionary of English Place-Names. Oxford University Press. pp. 150, 318. ISBN 0192831313.

- "Finlands Svenska Ortnamn (FSO), entry "Svin-"" (in Swedish). Institute for the Languages of Finland. Retrieved 2 January 2020.

- Horwitz, Richard P. (2002). Hog Ties: Pigs, Manure, and Mortality in American Culture. University of Minnesota Press. p. 23. ISBN 0816641838.

- "Fine Swine". The Daily Telegraph. 2 February 2001.

- Tarrow, Sidney (2013). "Chapter 5. Gender words". The language of contention: revolutions in words, 1688–2012. Cambridge University Press. p. 123. ISBN 978-1107036246.

Further reading

- Fabre-Vassas, Claudine (1997). The Singular Beast: Jews, Christians & the Pig. Columbia University Press. ISBN 0231103662.

- Harris, Marvin (1974). Cows, Pigs, Wars & Witches: The Riddles of Culture. Random House. ISBN 0394483383.

- Horwitz, Richard P. (2002). Hog Ties: Pigs, Manure, and Mortality in American Culture. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 0816641838.

- Lobban, Jr., R.A. (1994). "Pigs and Their Prohibition". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 26 (1): 57–75. doi:10.1017/S0020743800059766.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)