Botanical illustration

Botanical illustration is the art of depicting the form, color, and details of plant species, frequently in watercolor paintings. They must be scientifically accurate but often also have an artistic component and may be printed with a botanical description in books, magazines, and other media or sold as a work of art.[2] Often composed in consultation with a scientific author, their creation requires an understanding of plant morphology and access to specimens and references.

History

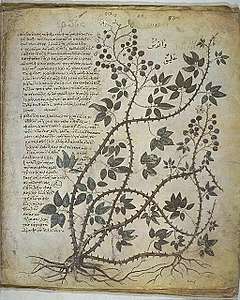

Early herbals and pharmacopoeia of many cultures have included the depiction of plants. This was intended to assist identification of a species, usually with some medicinal purpose. The earliest surviving illustrated botanical work is the Codex vindobonensis. It is a copy of Dioscorides's De Materia Medica, and was made in the year 512 for Juliana Anicia, daughter of the former Western Roman Emperor Olybrius.[3] The problem of accurately describing plants between regions and languages, before the introduction of taxonomy, was potentially hazardous to medicinal preparations. The low quality of printing of early works sometimes presents difficulties in identifying the species depicted.

%2C_late_19th_century%2C_NGA_52325.jpg)

When systems of botanical nomenclature began to be published, the need for a drawing or painting became optional. However, it was at this time that the profession of botanical illustrator began to emerge. The eighteenth century saw many advances in the printing processes, and the illustrations became more accurate in colour and detail. The increasing interest of amateur botanists, gardeners, and natural historians provided a market for botanical publications; the illustrations increased the appeal and accessibility of these to the general reader. The field guides, Floras, catalogues and magazines produced since this time have continued to include illustrations. The development of photographic plates has not made illustration obsolete, despite the improvements in reproducing photographs in printed materials. A botanical illustrator is able to create a compromise of accuracy, an idealized image from several specimens, and the inclusion of the face and reverse of the features such as leaves. Additionally, details of sections can be given at a magnified scale and included around the margins around the image.

Botanical illustration is a feature of many notable books on plants, a list of these would include:

Recently a renaissance has been occurring in botanical art and illustration. Organizations devoted to furthering the art form are found in the US (American Society of Botanical Artists), UK (Society of Botanical Artists), Australia (Botanical Art Society of Australia), and South Africa (Botanical Artists Association of South Africa), among others. The reasons for this resurgence are many. In addition to the need for clear scientific illustration, botanical depictions continue to be one of the most popular forms of "wall art" [4]. There is an increasing interest in the changes occurring in the natural world, and in the central role plants play in maintaining healthy ecosystems. A sense of urgency has developed in recording today's changing plant life for future generations. Working in media long understood provides confidence in the long-term conservation of the drawings, paintings, and etchings. Many artists are drawn to more traditional figurative work, and find plant depiction a perfect fit. Working with scientists, conservationists, horticulturists, and galleries locally and around the world, today's illustrators and artists are pushing the boundaries of what has traditionally been considered part of the genre.

See also

References

- "American Turk's cap Lily". Victoria and Albert Museum. Retrieved 2007-12-12.

- Sydney Living Museums (2016-07-13), The art in the illustration, retrieved 2016-07-29

- "Kew Gardens website".

- Antique botanical illustrations for use as home decor at Fine Rare Prints

Further reading

- De Bray, Lys (2001). The Art of Botanical Illustration: A history of classic illustrators and their achievements. Quantum Publishing, London. ISBN 1-86160-425-4.

- Blunt, Wilfrid and Stearn, William T. (1994). The Art of Botanical Illustration. Antique Collector's Club, London. ISBN 1-85149-177-5.

- Morris, Colleen; Louisa Murray: (2016). The Florilegium: the Royal Botanic Gardens Sydney celebrating 200 years: plants of the three gardens of the Royal Botanic Gardens and Domain Trust, The Florilegium Society at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Sydney. ISBN 978-099-447790-3

- Sherwood, Shirley (2001). A Passion for Plants: Contemporary Botanical Masterworks. Cassell and Co, London. ISBN 0-304-35828-2.

- Sherwood, Shirley and Rix, Martyn (2008). Treasures of Botanical Art. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. ISBN 978-1-84246-221-8.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Botanical illustrations. |

- American Society of Botanical Artists

- Art Serving Science: Solutions for the Preservation and Access of a Collection of Botanical Art and Illustration

- Botanical Art Society of Australia

- Botanical Drawings of carnivorous plants from the John Innes Centre Historical Collection

- Plantillustrations.org: searchable database of historic illustrations

- Botany.si.edu: online Smithsonian catalogue

- Flora of New Granada (Colombia) Drawings online, from the Royal Botanical Expedition led by Jose Celestino Mutis

- Traveling Artist Wildflowers Project

- University of Delaware: 'The Art of Botanical Illustration' exhibit