Gingerbread house

A gingerbread house is a novelty confectionery shaped like a building that is made of cookie dough, cut and baked into appropriate components like walls and roofing. The usual material is crisp ginger biscuit made of gingerbread – the ginger nut. Another type of model-making with gingerbread uses a boiled dough that can be moulded like clay to form edible statuettes or other decorations. These houses, covered with a variety of candies and icing, are popular Christmas decorations, often built by children with the help of their parents.

History

_Kirchweih.jpg)

Records of honey cakes can be traced to ancient Rome.[2] Food historians ratify that ginger has been seasoning foodstuffs and drinks since antiquity. It is believed gingerbread was first baked in Europe at the end of the 11th century, when returning crusaders brought back the custom of spicy bread from the Middle East.[3] Ginger was not only tasty, it had properties that helped preserve the bread. According to the French legend, gingerbread was brought to Europe in 992 by the Armenian monk, later saint, Gregory of Nicopolis (Gregory Makar). He lived for seven years in Bondaroy, France, near the town of Pithiviers, where he taught gingerbread cooking to priests and other Christians. He died in 999.[4][5][6] An early medieval Christian legend elaborates on the Gospel of Matthew's account of the birth of Jesus. According to the legend, attested to in a Greek document from the 8th century, of presumed Irish origin and translated into Latin with the title Collectanea et Flores, in addition to gold, frankincense, and myrrh, given as gifts by three "wise men from the east" (magi), ginger was the gift of one wise man (magus) who was unable to complete the journey to Bethlehem. As he was lingering in his last days in a city in Syria, the magus gave his chest of ginger roots to the Rabbi who had kindly cared for him in his illness. The Rabbi told him of the prophesies of the great King who was to come to the Jews, one of which was that He would be born in Bethlehem, which, in Hebrew, meant "House of Bread". The Rabbi was accustomed to having his young students make houses of bread to eat over time to nourish the hope for their Messiah. The Magus suggested adding ground-up ginger to the bread for zest and flavor. Gingerbread, as we know it today, descends from Medieval European culinary traditions. Gingerbread was also shaped into different forms by monks in Franconia, Germany in the 13th century. Lebkuchen bakers are recorded as early as 1296 in Ulm and 1395 in Nuremberg, Germany. Nuremberg was recognized as the "Gingerbread Capital of the World" when in the 1600s the guild started to employ master bakers and skilled workers to create complicated works of art from gingerbread.[3] Medieval bakers used carved boards to create elaborate designs. During the 13th century, the custom spread across Europe. It was taken to Sweden in the 13th century by German immigrants; there are references from Vadstena Abbey of Swedish nuns baking gingerbread to ease indigestion in 1444.[7][8] The traditional sweetener is honey, used by the guild in Nuremberg. Spices used are ginger, cinnamon, cloves, nutmeg and cardamom. Gingerbread figurines date back to the 15th century, and figural biscuit-making was practised in the 16th century.[9] The first documented instance of figure-shaped gingerbread biscuits is from the court of Elizabeth I of England: she had gingerbread figures made in the likeness of some of her important guests.[10]

History of gingerbread shaping

The gingerbread bakers were gathered into professional baker guilds. In many European countries gingerbread bakers were a distinct component of the bakers' guild. Gingerbread baking developed into an acknowledged profession. In the 17th century only professional gingerbread bakers were permitted to bake gingerbread except at Christmas and Easter, when anyone was allowed to bake it.[3]

In Europe gingerbreads were sold in special shops and at seasonal markets that sold sweets and gingerbread shaped as hearts, stars, soldiers, babies, riders, trumpets, swords, pistols and animals.[2] Gingerbread was especially sold outside churches on Sundays. Religious gingerbread reliefs were purchased for the particular religious events, such as Christmas and Easter. The decorated gingerbreads were given as presents to adults and children, or given as a love token, and bought particularly for weddings, where gingerbreads were distributed to the wedding guests.[2] A gingerbread relief of the patron saint was frequently given as a gift on a person's name day, the day of the saint associated with his or her given name.[2] It was the custom to bake biscuits and paint them as window decorations. The most intricate gingerbreads were also embellished with iced patterns, often using colours, and also gilded with gold leaf.[11] Gingerbread was also worn as a talisman in battle or as protection against evil spirits.[5]

Gingerbread was a significant form of popular art in Europe;[2] major centers of gingerbread mould carvings included Lyon, Nuremberg, Pest, Prague, Pardubice, Pulsnitz, Ulm, and Toruń. Gingerbread moulds often displayed actual happenings, by portraying new rulers and their consorts, for example. Substantial mould collections are held at the Ethnographic Museum in Toruń, Poland and the Bread Museum in Ulm, Germany. During the winter months medieval gingerbread pastries, usually dipped in wine or other alcoholic beverages, were consumed. In America, the German-speaking communities of Pennsylvania and Maryland continued this tradition until the early 20th century.[2] The tradition survived in colonial North America, where the pastries were baked as ginger snap cookies and gained favour as Christmas tree decorations.[2]

The tradition of making decorated gingerbread houses started in Germany in the early 1800s. According to certain researchers, the first gingerbread houses were the result of the well-known Grimm's fairy tale "Hansel and Gretel"[3] in which the two children abandoned in the forest found an edible house made of bread with sugar decorations. After this book was published, German bakers began baking ornamented fairy-tale houses of lebkuchen (gingerbread). These became popular during Christmas, a tradition that came to America with Pennsylvanian German immigrants.[12] According to other food historians, the Grimm brothers were speaking about something that already existed.[3]

Modern times

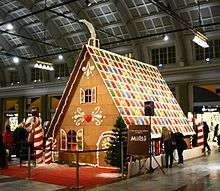

In modern times the tradition has continued in certain places in Europe. In Germany the Christmas markets still sell decorated gingerbread before Christmas. (Lebkuchenhaus or Pfefferkuchenhaus are the German terms for a gingerbread house.) Making gingerbread houses is still a way of celebrating Christmas in many families. They are built traditionally before Christmas using pieces of baked gingerbread dough assembled with melted sugar. The roof tiles can consist of frosting or candy. The gingerbread house yard is usually decorated with icing to represent snow.[13]

A gingerbread house does not have to be an actual house, although it is the most common. It can be anything from a castle to a small cabin, or another kind of building, such as a church, an art museum,[14] or a sports stadium,[15] and other items, such as cars, gingerbread men and gingerbread women, can be made of gingerbread dough.[16]

In most cases, royal icing is used as an adhesive to secure the main parts of the house, as it can be made quickly and forms a secure bond when set.

In Sweden gingerbread houses are prepared on Saint Lucy's Day. Since 1991, the people of Bergen, Norway, have built a city of gingerbread houses each year before Christmas. Named Pepperkakebyen (Norwegian for "the gingerbread village"), it is claimed to be the world's largest such city.[17] Every child under the age of 12 can make their own house at no cost with the help of their parents. In 2009, the people of Bergen were shocked when the gingerbread city was destroyed in an act of vandalism.[18] A group of building design, construction, and sales professionals in Washington, D.C., also collaborate on a themed "Gingertown" every year.[15]

In San Francisco, the Fairmont and St. Francis hotels display rival gingerbread houses during the Christmas season.[19]

Guinness World records

In 2013, a group in Bryan, Texas, USA, broke the Guinness World Record set the previous year for the largest gingerbread house, with a 2,520-square-foot (234 m2) edible-walled house in aid of a hospital trauma centre.[20] The gingerbread house had an estimated calorific value exceeding 35.8 million and ingredients included 2,925 pounds (1,327 kg) of brown sugar, 1,800 pounds (820 kg) of butter, 7,200 eggs and 7,200 pounds (3,300 kg) of general purpose flour.[20]

The executive sous-chef at the New York Marriott Marquis hotel, Jon Lovitch, broke the record for the largest gingerbread village with 135 residential and 22 commercial buildings, and cable cars and a train also made of gingerbread.[21] It was displayed at the New York Hall of Science. Another contender from Bergen, Norway made a gingerbread town called Pepperkakebyen.[22]

Gingerbread houses

- Gingerbread houses

Gingerbread house with candy

Gingerbread house with candy A gingerbread house with clock and candy decorations

A gingerbread house with clock and candy decorations Gingerbread house with double doors

Gingerbread house with double doors Gingerbread house with steps and trees

Gingerbread house with steps and trees Gingerbread house with path

Gingerbread house with path Gingerbread house with lighting

Gingerbread house with lighting Gingerbread house with snowman

Gingerbread house with snowman Gingerbread ship

Gingerbread ship- Gingerbread house as a Christmas Eve decoration

Gingerbread houses with Christmas tree

Gingerbread houses with Christmas tree.jpg) Gingerbread village with model trains

Gingerbread village with model trains Gingerbread house and Elizabeth Tower in London, United Kingdom

Gingerbread house and Elizabeth Tower in London, United Kingdom

See also

References

- List and amount of ingredients used (sign at rear of gingerbread house). Stockholm. 2009.

- "Gingerbread". enotes.com. Archived from the original on 12 December 2013. Retrieved 10 December 2013.

- Olver, Lynne. "Traditional Christmas foods" (PDF). The Food Timeline. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 December 2013. Retrieved 10 December 2013 – via City of Tea Tree Gully.

- La Confrérie du Pain d'Epices, archived from the original on 15 December 2013, retrieved 15 December 2013

- Le Pithiviers, archived from the original on 12 December 2013, retrieved 15 December 2013

- Monastère orthodoxe des Saints Grégoire Armeanul et Martin le Seul, archived from the original on 10 January 2014, retrieved 15 December 2013

- "History and tradition". Annas Pepparkakor. Archived from the original on 14 December 2013. Retrieved 10 December 2013.

- "Pepparkakan och dess historia". Danska Wienerbageriet. Archived from the original on 2 September 2013. Retrieved 10 December 2013.

- Campbell Franklin, Linda (1997). 300 Years of Kitchen Collectibles (4th ed.). Iowa, Wisconsin: Krause. p. 183. ISBN 9780896891128.

- "A History of Gingerbread Men". Ferguson Plarre Bakehouses. Archived from the original on 13 September 2009. Retrieved 13 November 2009.

- "Gingerbread (more)". Archived from the original on 10 December 2013. Retrieved 7 December 2013.

- "Holiday Tradition with Spicy History". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. 9 December 2001 (p. N-9).

- Brones, Anna. "The Magic of Swedish Gingerbread Cookies". Huffington Post. Archived from the original on 19 December 2013. Retrieved 14 December 2013.

- "Gingerbread Architecture Makes Normal Gingerbread Houses Look Pathetic". Huffington Post. 3 December 2013.

- Basch, Michelle (5 December 2013). "'Gingertown' brings modern twist to gingerbread houses". WTOP-FM.

- "Gingerbread model houses COOP" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 December 2011. Retrieved 8 December 2013.

- "Pepperkakebyen i Bergen" (in Norwegian and English). Archived from the original on 12 December 2010. Retrieved 23 December 2010.

- Rolleiv Solholm (23 November 2009). "Bergen's "Gingerbread City" vandalized". The Norway Post. Archived from the original on 22 December 2010. Retrieved 23 December 2010.

- Rubenstein, Steve (3 December 2013). "The great San Francisco gingerbread war commences". San Francisco Chronicle.

- Herskovitz, Jon (6 December 2013). "With nearly a ton of butter, Texas gingerbread house sets record". Texas A &M University / Reuters.

- "Largest gingerbread village: Chef Jon Lovitch breaks Guinness World Records' record". World Record Academy. 3 December 2013.

- Wilson, Antonia (22 December 2018). "A brief history of the gingerbread house". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

Further reading

- Weaver, William Woys – The Christmas Cook, Three Centuries of American Yuletide Sweets.

- Eliza Leslie Miss Leslie's New Cookery Book – The Original Classic Edition Miss Leslie's New Cookery Book, online

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gingerbread houses. |

| Wikibooks Cookbook has a recipe/module on |

- Gingerbread at the Open Directory Project

- Facebook Fan Page