Siamese fighting fish

The Siamese fighting fish (Betta splendens), also known as the betta, is a popular fish in the aquarium trade. Bettas are a member of the gourami family and are known to be highly territorial. Males in particular are prone to high levels of aggression and will attack each other if housed in the same tank. If there is no means of escape, this will usually result in the death of one or both of the fish. Female bettas can also become territorial towards each other if they are placed in too small an aquarium. It is typically not recommended to keep male and female bettas together, except temporarily for breeding purposes which should always be undertaken with caution.[2]

| Siamese fighting fish | |

|---|---|

| |

| Halfmoon male displaying his flared opercula | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Anabantiformes |

| Family: | Osphronemidae |

| Genus: | Betta |

| Species: | B. splendens |

| Binomial name | |

| Betta splendens Regan, 1910 | |

This species is native to the Mekong basin of Thailand, Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam and is mostly concentrated in the Chao Phraya river in Thailand. The fish can be found in standing waters of canals, rice paddies and floodplains.[3] It is listed as Vulnerable by the IUCN. On 5 February 2019, Thailand's council of ministers confirmed "Siamese fighting fish" as Thailand's national aquatic animal.[4][5]

Description

B. splendens usually grows to a length of about 7 cm (2.8 in).[3] Although aquarium specimens are widely known for their brilliant colors and large, flowing fins, the natural coloration of B. splendens is generally green, brown and grey, and the fins of wild specimens are short. In the wild, they exhibit strong colors only when agitated. In captivity, they have been selectively bred to display a vibrant array of colors and tail types.[6]

Conservation status

Although popular as an aquarium fish, the IUCN has classified B. splendens in the vulnerable category.[7] The fish is naturally endemic to Thailand and can be found in shallow areas in marshes or paddy fields.[7] The primary threat is due to habitat destruction and pollution, as farmlands continue to be developed across central Thailand.[7]

Diet

Betta splendens feed on zooplankton, crustaceans, and the larvae of mosquitoes and other water-bound insects.[8] In captivity they can be fed a varied diet of pellets or frozen foods such as brine shrimp, bloodworms, daphnia and many others.

Reproduction and early development

Male bettas will flare their gills, spread their fins and twist their bodies in a dance if interested in a female. If the female is also interested she will darken in color and develop vertical lines known as breeding bars as a response. Males build bubble nests of various sizes and thicknesses at the surface of the water. Most tend to do this regularly even if there is no female present.

Plants or rocks that break the surface often form a base for bubble nests. The act of spawning itself is called a "nuptial embrace", for the male wraps his body around the female; around 10–40 eggs are released during each embrace, until the female is exhausted of eggs. The male, in his turn, releases milt into the water, and fertilization takes place externally. During and after spawning, the male uses his mouth to retrieve sinking eggs and deposit them in the bubble nest (during mating the female sometimes assists her partner, but more often she simply devours all the eggs she manages to catch). Once the female has released all of her eggs, she is chased away from the male's territory, as she will likely eat the eggs.[9] If she is not removed from the tank then she will most likely be killed by the male.

The eggs will remain in the male's care. He carefully keeps them in his bubble nest, making sure none fall to the bottom, repairing the bubble nest as needed. Incubation lasts for 24–36 hours; newly hatched larvae remain in the nest for the next two to three days until their yolk sacs are fully absorbed. Afterwards, the fry leave the nest and the free-swimming stage begins. In this first period of their lives, B. splendens fry are totally dependent on their gills; the labyrinth organ which allows the species to breathe atmospheric oxygen typically develops at three to six weeks of age, depending on the general growth rate, which can be highly variable. B. splendens can reach sexual maturity at an age as early as 4–5 months.

History

Fighting fish

Some people of Thailand and Malaysia are known to have collected these fish prior to the 19th century from the wild which are line-bred for aggression in eastern Thailand.

In the wild, betta spar for only a few minutes before one fish backs off. Bred specifically for heightened aggression, domesticated betta matches can go on for much longer, with winners determined by a willingness to continue fighting. Once a fish retreats, the match is over.

Seeing the popularity of these fights, the king of Thailand, Rama III, started licensing and collecting these fighting fish. In 1840, he gave some of his prized fish to a man who, in turn, gave them to Theodore Edward Cantor, a medical scientist. Nine years later, Cantor wrote an article describing them under the name Macropodus pugnax. In 1909, the ichthyologist Charles Tate Regan, upon realizing a species was already named Macropodus pugnax, renamed the domesticated Siamese fighting fish Betta splendens.[10]

The vernacular name "plakat", often applied to the short-finned ornamental strains, is derived from the Thai word pla kat (Thai: ปลากัด), which literally means "biting fish" and is the Thai name for all members of the B. splendens species complex (as all members have aggressive tendencies in the wild and all are extensively line-bred for aggression in eastern Thailand) rather than for any specific strain(s) of the Siamese fighting fish. So the term "fighting fish" comes in use to generalize all the members of the B. splendens species complex including the Siamese fighting fish.[11][12]

Aquarium fish

In 1892, this species was imported to France by the French aquarium fish importer Pierre Carbonnier in Paris, and in 1896, the German aquarium fish importer Paul Matte in Berlin imported the first specimens to Germany from Moscow.

Invasive species

In January 2014 a large population of the fish was discovered in the Adelaide River Floodplain in the Northern Territory, Australia.[13] As an invasive species they pose a threat to native fish, frogs and other wetland wildlife.[13]

In the aquarium

Water

Betta species prefer a water temperature of around 75–82 °F (24–28 °C) but have been seen to survive temporarily at the extremes of 56 °F (13 °C) or 95 °F (35 °C). When kept in colder climates, aquarium heaters are recommended.[14]

Bettas are also affected by the pH levels of the water. Ideal levels for Bettas would be at a neutral pH (7.0) However, Bettas are slightly tolerant towards the pH levels.[15] They have an organ known as the labyrinth organ which allows them to breathe air at the water's surface. This organ was thought to allow the fish to be kept in unmaintained aquaria,[16] but this is a misconception, as poor water quality makes all tropical fish, including Betta splendens, more susceptible to diseases such as fin rot.

Properly kept and fed a correct diet, Siamese fighting fish generally live between 3 and 5 years in captivity, but may live between 7 and 10 years in rare cases.

Aquarium size and cohabitants

The minimum tank size is directly related to how experienced the fish keeper is, and how often they want to carry out water changes, in order to keep the water pristine. The Betta must of course have enough room to turn around, but there is no evidence that they require a lot of space. Due to their labyrinth organ they are not dependent on high oxygen levels in the water, so a large surface area for gas exchange is not required. Some Betta enthusiasts claim that there is a minimum tank size for a Betta, but to try to set a strict baseline minimum is somewhat arbitrary.. Reliably performing regular partial water changes (every other day for small unfiltered tanks) would at least ensure the water quality in a smaller tank is acceptable. Most consider 9 to 19 litres ( 3 - 5 US gallons) to be an ideal tank size for a Betta, "but you can successfully keep a Betta in a 4 litre (1 gallon) tank provided you clean it regularly" and maintain an acceptable temperature (generally 24°C to 26°C - 75F to 78F - is considered optimal).[17]

Bettas can cohabit with fish that are bottom feeders, however it is not advised to keep them with feeders that may eat their fins or destroy the slime coat (one example is the Siamese Algae Eater, if kept in an inappropriately sized tank)

Varieties

B. splendens can be hybridized with B. imbellis, B. mahachaiensis, and B. smaragdina, though with the latter, the fry tend to have low survival rates. In addition to these hybrids within the genus Betta, intergeneric hybridizing of Betta splendens and Macropodus opercularis, the paradise fish, has been reported.[18]

Breeders around the world continue to develop new varieties. Often, the males of the species are sold preferentially in stores because of their beauty, compared to the females. Females almost never develop fins as showy as males of the same type and are often more subdued in coloration, though some breeders manage to get females with fairly long fins and bright colors.

Colors

Wild fish exhibit strong colours only when agitated. Breeders have been able to make this coloration permanent, and a wide variety of hues breed true. Colours available to the aquarist include red, orange, yellow, blue, steel blue, turquoise/green, black, pastel, white ("opaque" white, not to be confused with albino) and multi-coloured fish.

Bettas are found in many different colours due to different layers of pigmentation in their skin. The layers (from furthest within to the outer layer) consists of red, yellow, black, iridescent (blue and green), and metallic (not a colour of its own, but reacts with the other colours to change how they are perceived). Any combination of these layers can be present, leading to a wide variety of colours.[19]

The shades of blue, turquoise, and green are slightly iridescent, and can appear to change colour with different lighting conditions or viewing angles; this is because these colours (unlike black or red) are not due to pigments, but created through refraction within a layer of translucent guanine crystals. Breeders have also developed different colour patterns such as marble and butterfly, as well as metallic shades through hybridization[20] like copper, gold, or platinum (these were obtained by crossing B. splendens to other Betta species).

A true albino betta has been feverishly sought since one recorded appearance in 1927, and another in 1953. Neither of these was able to establish a line of true albinos. In 1994, a hobbyist named Kenjiro Tanaka claimed to have successfully bred albino bettas.[21]

Some bettas will change colours throughout their lifetime (known as marbling), attributed to a transposon.[22]

Koi bettas have mutated now and some are no longer marbles and do not change colors or patterns through out their lifetime (known as true Koi) attributed to the defective gene that causes marbling not being repaired in the color layers after a time.[23]

Common Colours[24]

- Super Red

- Super Blue

- Super Yellow

- Opaque

- Super Black

- Super White

- Orange

- Marble

- Candy

- Nemo

- Galaxy Nemo

- Koi

- Alien

- Copper

- Cellophane

- Gold

- Galaxy Koi

Rarer Colours[24]

- Super Orange

- Metallic

- Turquoise

- Lavender

- Mustard Gas

- Grizzle

- Green

Colour patterns[24]

- Solid – The entire fish is one colour with no variations

- Bi-colour – The fins must be a different colour to the body to be a Bi-colour.

- Cambodian – The body is pale, almost colourless, and the fins are a solid colour

- Butterfly – The fins have distinct bands of colours

- Marble – Irregular patterns throughout the body and fin

- Piebald – pale flesh-coloured face irrespective of the body colour.

- Full Mask – the face being the same colour as the body rather than what it would naturally be which would be darker than the body

- Dragon – rich strong base colour with the scales on the main part of the body a pale iridescent

- Multicolour – 3 or more colours on the body that does not fit into any other pattern category

- Pastel – A light shade of colour seen only on the fins, body remains a flesh hue.

- Koi - Koi are judged from the top down and look like their carp counterparts. Patterns should be uniform with clean color defining lines.

- Nemo - are either white based or orange based and have 3 or 4 main colors. Orange, red, yellow, black

Finnage variations[24]

Breeders have developed several different finnage and scale variations:

- Veil tail - extended finnage length and non-symmetrical tail; caudal fin rays usually only split once; the most common tail type seen in pet stores.

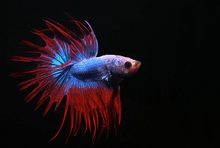

- Crown tail - fin rays are extended well beyond the membrane and consequently the tail can take on the appearance of a crown; also called fringetail

- Comb tail - less extended version of the crown tail, derived from breeding crown and another finnage type

- Half-moon - "D" shaped caudal fin that forms a 180° angle, the edges of the tail are crisp and straight

- Over-half-moon or Super Delta tail - caudal fin is in excess of the 180° angle, byproduct of trying to breed half-moons, can sometimes cause problems because the fins are too big for the fish to swim properly[25]

- Rose tail - variation with so much finnage that it overlaps and looks like a rose

- Feather tail - similar to the rose tail, with a rougher appearance

- Plakat - short fins that resemble the fins seen in wild-type bettas

- Half-moon plakat - short-finned half-moon; plakat and half-moon cross

- Double tail or Full-moon - the tail fin is duplicated into two lobes and the dorsal fin is significantly elongated, the two tails can show different levels of bifurcation depending on the individual

- Delta tail - tail spread less than that of a half-moon [<180]

- Super Delta (aka SD or SDT for short) - are an enhanced version of the Delta. They are one step closer to the Halfmoon variety in that their tails have a span between 130 -170 degrees

- Half-sun - combtail with caudal fin going 180°, like a half-moon

- Elephant ear - pectoral fins are much larger than normal, often white, resembling the ears of an elephant

- Spade tail - caudal fin has a wide base that narrows to a small point

Behavior

Males and females flare or puff out their gill covers (opercula) to appear more impressive, either to intimidate other rivals or as an act of courtship. Other reasons for flaring can include when they are intimidated by movement or change of scene in their environments. Both sexes display pale horizontal bars if stressed or frightened. However, such colour changes, common in females of any age, are rare in mature males due to their intensity of colour. Females often flare at other females, especially when setting up a pecking order. Flirting fish behave similarly, with vertical instead of horizontal stripes indicating a willingness and readiness to breed (females only). Betta splendens enjoy a decorated tank, being a territorial fish it is necessary to establish territory even when housed alone. They may set up a territory centered on a plant or rocky alcove, sometimes becoming highly possessive of it and aggressive toward trespassing rivals. This is the reason why when kept with other fish the minimum tank size should be 45 litres (about 10 gallons). Contrary to popular belief, bettas are compatible with many other species of aquarium fish.[26] Given the proper parameters bettas will be known to only be aggressive towards smaller and slower fish than themselves such as guppies.[27]

The aggression of this fish has been studied by ethologists and comparative psychologists.[28] These fish have historically been the objects of gambling; two male fish are pitted against each other to fight and bets are placed on which one will win. One fish will arise the victor, the fight continuing until one participant is submissive. These competitions can result in the death of either one or both fish depending on the seriousness of their injuries. To avoid fights over territory, male Siamese fighting fish are best isolated from one another. Males will occasionally even respond aggressively to their own reflections in a mirror. Though this is obviously safer than exposing the fish to another male, prolonged sight of their reflection may lead to stress in some individuals. Not all Siamese fighting fish respond negatively to other males, especially when the tank is large enough for each fish to create their own designated territory.[29]

Aggressive behavior in females

In general, studies have shown that females exhibit similar aggressive behaviors as their male counterparts, but these behaviors are less common.[30] A group of female Siamese fighting fish were observed over a period of two weeks. During these two weeks, the following behaviors were recorded: attacking, displays, and biting food. The results of this observational study indicated that when females are housed in small groups, they form a stable dominance order. For example, the fish who was ranked at the top showed higher levels of mutual displays, in comparison to the fish who were of lower ranks. The researchers also found that the duration of the displays differed depending on whether an attack occurred.[31] The results of these studies indicate that female Siamese fighting fish should be considered as often as males, as there are evidently interesting variations in their behaviors as well.

Courtship behavior

There has been numerous research in the area of courtship behavior between male and female Siamese fighting fish. This research has focused on the aggressive behaviors of males during the courtship process. For example, one study found that when male fish are in the bubble nest phase, their aggression toward females is quite low. This is due to the males attempting to attract potential mates to their nest, so eggs can successfully be laid.[32] It has also been found that in regards to mate choice, females often “eavesdrop” on pairs of male Siamese fighting fish while they are fighting. When females witness aggressive behavior between a pair of males, the female is more likely to be attracted to the male who won. In contrast, if a female did not “eavesdrop” on aggressive behavior between a pair of males, the female will show no preference in mate choice. In regards to the male fish, the “loser” fish are more likely to attempt to court the fish who did not “eavesdrop”. The “winner” fish have been found to show no preference in regards to female fish who “eavesdropped” and those who did not.[33]

One study considered the ways in which male Siamese fighting fish alter their behaviors during courtship when another male is present. During this experiment, a dummy female was placed in the tank. The researchers expected that males would conceal their courtship from intruders, however this surprisingly was not the case. It was found that when another male fish was present, the male was more likely to engage in courtship behaviors with the dummy female fish. When no barriers were present, the males were more likely to engage in gill flaring at an intruder male fish. Therefore, the researchers conclude that the male is attempting to court the female and communicate with the rival male present at the same time.[34] These results indicate the importance of considering courtship behavior, as the literature has suggested there are many factors that can dramatically affect the ways in which both male and females can act in courtship settings.

Metabolic costs of aggression

Studies have found that Siamese fighting fish often begin with behaviors that require high cost, and gradually decrease their behaviors as the encounter proceeds.[32] This indicates that Siamese fighting fish will first begin an encounter using much metabolic energy, but will gradually decrease, as to not use too much energy, thus making the encounter a waste if the fish is not successful. Similarly, researchers have found that when pairs of male Siamese fighting fish were kept together in the same tank for a three-day period, aggressive behavior was most prevalent during the mornings of the first two days of their cohabitation. However the researchers observed that the fighting between the two males decreased as the day progressed. The male in the dominant position initially had metabolic advantage; although as the experiment progressed, both fish became equal in regards to metabolic advantages.[35] In regards to oxygen consumption, one study found that when two male Siamese fighting fish fought, the metabolic rates of both fish did not differ before or during the fight. However, the fish who won showed higher oxygen consumption during the evening subsequent to the fight. Therefore, the results of this study indicate that aggressive behavior in the form of fighting has long-lasting effects on metabolism.[36]

Effects of chemical exposure on behavior

Chemicals such as hormones can have powerful effects on the behavior of an individual. Researchers have considered the effect that such chemicals can have on Siamese fighting fish. This section will examine three studies, each of which indicates that chemicals can significantly affect the behaviors of Siamese fighting fish. In particular, these behavior changes are most likely to occur in regards to aggression.

One study investigated the effect of testosterone on female Siamese fighting fish. Females were first given testosterone, which resulted in physical changes. This included fin length, body coloration and gonads. These physical changes resulted in the females resembling typical male fish. Next their aggressive behavior was monitored. It was found that when these females interacted with other females, their aggression increased. In contrast, when the females interacted with males, their aggressive behavior decreased. The researchers then allowed the female fish to interact socially with a group of other female fish, who had not been exposed to testosterone. It was found that when the female fish stopped receiving testosterone, those who were exposed to the female fish still exhibited the male typical behaviors. In contrast, the female fish who were kept isolated did not continue to exhibit the male typical behaviors after testosterone was discontinued.[37]

Another study exposed male Siamese fighting fish to endocrine-disrupting chemicals. The researchers were curious if exposure to these chemicals would affect the ways in which females respond to the exposed males. It was found that when shown videos of the exposed males, the females favored those who were not exposed to the endocrine-disrupting chemicals, and avoided those male who were exposed. Therefore, the researchers concluded that exposure to these chemicals can negatively affect the mating success of male Siamese fighting fish.[38]

The last study investigated the effect of the SSRI, fluoxetine, on male Siamese fighting fish. It has been previously found that this chemical reduces aggressive behavior; therefore, researchers were curious if this would occur in their experiment. As predicted, it was found that when exposed to fluoxetine, male Siamese fighting fish exhibited less aggressive behavior than they would have if they had not been exposed to the chemical.[39]

Name

Although commonly called a betta in the aquarium trade, especially in North America, that is the name of a genus not only containing this fish, but also other species. B. splendens is more accurately called by its scientific name or "Siamese fighting fish", to avoid confusion with the other species in the genus.

In popular culture

- The Fisheries Department of Thailand is promoting pla kat, or Siamese fighting fish, as the national fish. Department chief Adisorn Promthep said that the proposal will be submitted to the National Identity Office under the Prime Minister's Office for approval. He said that once the status is recognised, fighting fish farming would be promoted, which would generate money and create jobs. He added that credible records show that pla kat of the Betta splendens species are native to Thailand and were first collected for fighting during the reign of King Rama III.[40]

- The titular character in the novel Rumble Fish and subsequent film adaptation is a Siamese fighting fish.[41] In both, the character Motorcycle Boy is fascinated with the creatures and dubs them "rumble fish". He speculates that if the fish were to be set free in the river, they wouldn't behave so aggressively. A common misconception regarding keeping B. splendens is that they should live in vases or bowls. However, this has been proven to damage their health, life expectancy, and cause negative behavioral changes.[42]

- A scene in the James Bond film From Russia with Love shows three Siamese fighting fish in an aquarium as the villain Ernst Stavro Blofeld likens the modus operandi of his criminal organisation, SPECTRE, to one of the fish that observes as the other two fight to the death, then kills the weakened victor.[43]

References

- Vidthayanon, C. (2011). "Betta splendens.". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2019: e.T180889A7653828. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2011-1.RLTS.T180889A7653828.en.

- "Guidelines released for keeping Fighters". Practical Fishkeeping Magazine. Retrieved 15 March 2017.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2014). "Betta splendens" in FishBase. February 2014 version.

- Limited, Bangkok Post Public Company. "Siamese fighting fish confirmed as national aquatic animal". bangkokpost.com. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- AFP (2019-02-05). "Thailand makes Siamese fighting fish national aquatic animal". Business Standard India. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- "Bubbles & Bettas: Tail Types and Patterns". Bubbles & Bettas. Archived from the original on 2016-11-22. Retrieved 2017-01-31.

- "Betta splendens (Siamese Fighting Fish)". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved 2018-03-15.

- "betta food". Bettatalk.com. Retrieved 2012-08-01.

- "Betta Fish Spawn: Guide from Preparing Breeding Tank to Feeding the Fry". Leaffin.com. 8 November 2017. Retrieved 1 April 2019.

- "Betta Origins". Betta Fish Center. Retrieved 11 June 2011.

- "Betta splendens – Siamese Fighting Fish (Micracanthus marchei)". Retrieved 1 April 2019.

- "Betta Fish Information; Plakats, Veiltails, Halfmoon, Crowntail". Americanaquariumproducts.com. Retrieved 1 April 2019.

- Bray, Dianne. "Siamese Fighting Fish, Betta splendens". Fishes of Australia. Retrieved 29 September 2014.

- "Ideal Water Temperature for Betta Fish | The Aquarium Club". Theaquarium.club. Retrieved 2017-11-19.

- "Betta water". Bettatalk.com. Retrieved 2015-10-05.

- Caller, Steven. "Betta Fish Introduction". My Betta Fish. Retrieved 2012-08-01.

- Gordon, H. Betta Pals Betta Guide.

- "Betta Splendens & Siamese Fighting Fish". Retrieved 1 April 2019.

- Griffin, Gerald (January 2016). "Betta Primer". Amazonas.

- "Metallics and Masked". Betty

Splendens.

com. - "Albino image" (JPG). Bettas-jimsonnier.com. Retrieved 2012-08-01.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-10-22. Retrieved 2014-10-22.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Koi vs Marble Betta". Worldbettas.com. 2 May 2018. Retrieved 1 April 2019.

- "Colors & Patterns". Bettasource.com. Retrieved 2015-10-04.

- "Grundlegendes über die Fischgabel" (in German). Fischbesteck24.de.

- "7 Excellent Betta Tank Mates for Your Siamese Fighting Fish". Retrieved 2015-08-20.

- "Betta Fish Facts". Earthsfriends.com. Retrieved 2015-08-20.

- Bronstein, Paul M. (1998). "Agonistic Sequences and the Assessment of Opponents in Male Betta splendens". American Journal of Psychology. 265 (2): 163–177. JSTOR 1422809.

- "Complete Betta Fish Care Guide (Tank, Diet & Aggression)". Retrieved 2016-03-03.

- Elcoro, Mirari; Da Silva, Stephanie; Lattal, Kennon (2008). "Visual Reinforcement in the Female Siamese Fighting Fish, Betta Splendens". Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 90 (1): 53–60. doi:10.1901/jeab.2008.90-53. PMC 2441580. PMID 18683612.

- Elwood, R.W.; Rainey, C.J. (1983). "Social Organization and Aggression Within Small Groups of Female Siamese Fighting Fish, Betta Splendens". Aggressive Behavior. 9 (4): 303–308. doi:10.1002/1098-2337(1983)9:4<303::aid-ab2480090404>3.0.co;2-5.

- Forsatkar, Mohammad; Nematollahi, Mohammad; Bron, Culum (August 2016). "Male Siamese Fighting Fish Use Gill Flaring As The First Display Towards Territorial Intruders". Journal of Ethology. 35: 51–59. doi:10.1007/s10164-016-0489-1.

- Herb, Brodie M.; Biron, Suzanne A.; Kidd, Michael R. (2003). "Courtship By Subordinate Male Simease Fighting Fish, Betta Splendens: Their Response to Eavesdropping and Niave Females". Behaviour. 140 (1): 71–78. doi:10.1163/156853903763999908. JSTOR 4536011.

- Dzieweczynski, Teresa L.; Lyman, Sarah; Poor, Elysia A. (2008). "Male Siamese Fighting Fish, Betta Splendens, Increase Rather Than Conceal Courtship Behaviour When a Rival is Present". Ethology. 115 (2): 186–195. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0310.2008.01602.x.

- Haller, Jozesf (1994). "Biochemical Costs of a Three Day Long Cohabitation in Dominant and Submissive Male Betta Splenons". Aggressive Behavior. 20 (5): 369–378. doi:10.1002/1098-2337(1994)20:5<369::aid-ab2480200504>3.0.co;2-f.

- Castro, Nidia; Ros, Albert F.H.; Becker, Klaus; Oliveira, Rui F. (2006). "Metabolic Costs of Aggressive Behaviour in the Siamese Fighting Fish, Betta Splendons". Aggressive Behavior. 32 (5): 474–480. doi:10.1002/ab.20147. hdl:10400.12/1283.

- Badura, Lori L.; Freidman, Herbert (1988). "Sex Reversal in Female Betta Splendons as a Function of Testosterone Manipulation and Social Influence". Journal of Comparative Psychology. 102 (3): 262–268. doi:10.1037/0735-7036.102.3.262. PMID 3180734.

- Dzieeczynski, Teresea L.; Kane, Jessica L. (2017). "The Bachorlette: Female Siamese Fighting Fish Avoid Males Exposed to an Estrogen Mimic". Behavioural Processes. 140: 169–173. doi:10.1016/j.beproc.2017.05.005. PMID 28478321.

- Eisenreich, Benjamin; Greene, Susan; Szalda-Petree, Allen (2017). "Of Fish and Mirrors: Fluoxetine Disrupts Aggression and Learning For Social Rewards". Physiology & Behavior. 173: 258–262. doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2017.02.021. PMID 28237550.

- "'Pla gud' to be national fish". Bangkok Post. 6 November 2018. Retrieved 6 November 2018.

- Hinton, S.E. (2013). Rumble Fish. Delacorte Press. ISBN 978-0385375689.

- "Why betta bowls are bad". Aquariadis.come. Retrieved 18 January 2018.

- Moore, Roger (2012). "The Spector of Evil". Bond on Bond: The Ultimate Book on 50 Years of Bond Movies. Michael O'Mara Books. ISBN 978-1843178613.

Further reading

- Simpson, M. J. A. (1968). "The display of the Siamese fighting fish Betta splendens". Animal Behaviour Monographs. 1: 1–73. doi:10.1016/S0066-1856(68)80001-9.

- Thompson, T (1966). "Operant and Classically-Conditioned Aggressive Behavior in Siamese Fighting Fish". American Zoologist. 6 (4): 629–741. doi:10.1093/icb/6.4.629. PMID 6009828.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Betta splendens. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Betta splendens |

| The Wikibook Do-It-Yourself has a page on the topic of: Breed siamese fighting fish |