Perugia

Perugia (/pəˈruːdʒə/,[3][4] also US: /-dʒiə, peɪˈ-/,[5] Italian: [peˈruːdʒa] (![]()

Perugia | |

|---|---|

| Comune di Perugia | |

Piazza IV Novembre | |

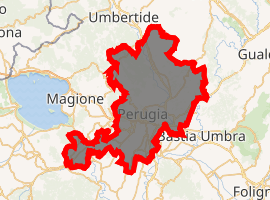

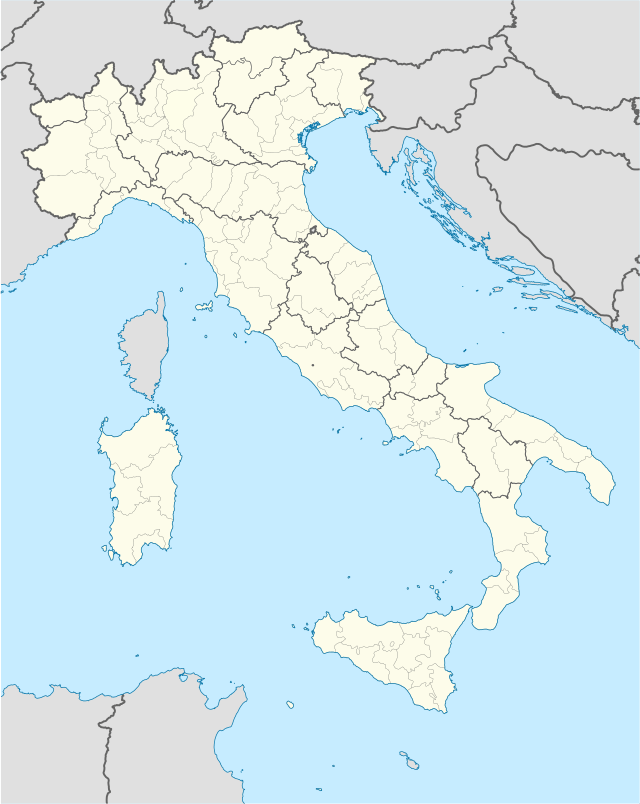

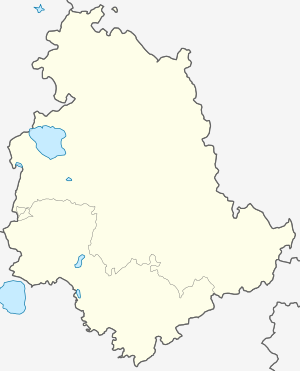

Location of Perugia

| |

Perugia Location of Perugia in Umbria  Perugia Perugia (Umbria) | |

| Coordinates: 43°6′44″N 12°23′20″E | |

| Country | Italy |

| Region | Umbria |

| Province | Perugia (PG) |

| Frazioni | See list |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Andrea Romizi (Forza Italia) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 449.92 km2 (173.72 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 493 m (1,617 ft) |

| Population (30 September 2010)[2] | |

| • Total | 168,066 |

| • Density | 370/km2 (970/sq mi) |

| Demonym(s) | Perugino |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 06100 |

| Dialing code | 075 |

| Patron saint | St. Constantius, St. Herculanus, St. Lawrence |

| Saint day | 29 January |

| Website | Official website |

The history of Perugia goes back to the Etruscan period; Perugia was one of the main Etruscan cities.

The city is also known as the universities town, with the University of Perugia founded in 1308 (about 34,000 students), the University for Foreigners (5,000 students), and some smaller colleges such as the Academy of Fine Arts "Pietro Vannucci" (Italian: Accademia di Belle Arti "Pietro Vannucci") public athenaeum founded in 1573, the Perugia University Institute of Linguistic Mediation for translators and interpreters, the Music Conservatory of Perugia, founded in 1788, and other institutes.

Perugia is also a well-known cultural and artistic centre of Italy. The city hosts multiple annual festivals and events, e.g., the Eurochocolate Festival (October), the Umbria Jazz Festival (July), and the International Journalism Festival (in April), and is associated with multiple notable people in the arts.

The painter Pietro Vannucci, nicknamed Perugino, was a native of Città della Pieve, near Perugia. He decorated the local Sala del Cambio with a series of frescoes; eight of his pictures can also be seen in the National Gallery of Umbria.[6]

Perugino was the teacher of Raphael,[7] the great Renaissance artist who produced five paintings in Perugia (today no longer in the city)[8] and one fresco.[9] Another painter, Pinturicchio, lived in Perugia. Galeazzo Alessi is the most famous architect from Perugia.

The city's symbol is the griffin, which can be seen in the form of plaques and statues on buildings around the city.

History

Perugia was an Umbrian settlement[10] but first appears in written history as Perusia, one of the 12 confederate cities of Etruria;[10] it was first mentioned in Q. Fabius Pictor's account, utilized by Livy, of the expedition carried out against the Etruscan League by Fabius Maximus Rullianus[11] in 310 or 309 BC. At that time a thirty-year indutiae (truce) was agreed upon;[12] however, in 295 Perusia took part in the Third Samnite War and was reduced, with Volsinii and Arretium (Arezzo), to seek for peace in the following year.[13]

In 216 and 205 BC it assisted Rome in the Second Punic War but afterwards it is not mentioned until 41–40 BC, when Lucius Antonius took refuge there, and was reduced by Octavian after a long siege, and its senators sent to their death. A number of lead bullets used by slingers have been found in and around the city.[14] The city was burnt, we are told, with the exception of the temples of Vulcan and Juno—the massive Etruscan terrace-walls,[15] naturally, can hardly have suffered at all—and the town, with the territory for a mile round, was allowed to be occupied by whoever chose. It must have been rebuilt almost at once, for several bases for statues exist, inscribed Augusto sacr(um) Perusia restituta; but it did not become a colonia, until 251–253 AD, when it was resettled as Colonia Vibia Augusta Perusia, under the emperor C. Vibius Trebonianus Gallus.[16]

It is hardly mentioned except by the geographers until it was the only city in Umbria to resist Totila, who captured it and laid the city waste in 547, after a long siege, apparently after the city's Byzantine garrison evacuated. Negotiations with the besieging forces fell to the city's bishop, Herculanus, as representative of the townspeople.[17] Totila is said to have ordered the bishop to be flayed and beheaded. St. Herculanus (Sant'Ercolano) later became the city's patron saint.[18]

In the Lombard period Perugia is spoken of as one of the principal cities of Tuscia.[19] In the 9th century, with the consent of Charlemagne and Louis the Pious, it passed under the popes; but by the 11th century its commune was asserting itself, and for many centuries the city continued to maintain an independent life, warring against many of the neighbouring lands and cities— Foligno, Assisi, Spoleto, Todi, Siena, Arezzo etc. In 1186 Henry VI, rex romanorum and future emperor, granted diplomatic recognition to the consular government of the city; afterward Pope Innocent III, whose major aim was to give state dignity to the dominions having been constituting the patrimony of St. Peter, acknowledged the validity of the imperial statement and recognised the established civic practices as having the force of law.[20]

On various occasions the popes found asylum from the tumults of Rome within its walls, and it was the meeting-place of five conclaves (Perugia Papacy), including those that elected Honorius III (1216), Clement IV (1265), Celestine V (1294), and Clement V (1305); the papal presence was characterised by a pacificatory rule between the internal rivalries.[20] But Perugia had no mind simply to subserve the papal interests and never accepted papal sovereignty: the city used to exercise a jurisdiction over the members of the clergy, moreover in 1282 Perugia was excommunicated due to a new military offensive against the Ghibellines regardless of a papal prohibition. On the other hand, side by side with the 13th century bronze griffin of Perugia above the door of the Palazzo dei Priori stands, as a Guelphic emblem, the lion, and Perugia remained loyal for the most part to the Guelph party in the struggles of Guelphs and Ghibellines. However this dominant tendency was rather an anti-Germanic and Italian political strategy.[20] The Angevin presence in Italy appeared to offer a counterpoise to papal powers: in 1319 Perugia declared the Angevin Saint Louis of Toulouse "Protector of the city's sovereignty and of the Palazzo of its Priors"[21] and set his figure among the other patron saints above the rich doorway of the Palazzo dei Priori. Midway through the 14th century Bartholus of Sassoferrato, who was a renowned jurist, asserted that Perugia was dependent upon neither imperial nor papal support.[20] In 1347, at the time of Rienzi's unfortunate enterprise in reviving the Roman republic, Perugia sent ten ambassadors to pay him honour; and, when papal legates sought to coerce it by foreign soldiers, or to exact contributions, they met with vigorous resistance, which broke into open warfare with Pope Urban V in 1369; in 1370 the noble party reached an agreement signing the treaty of Bologna and Perugia was forced to accept a papal legate; however the vicar-general of the Papal States, Gérard du Puy, Abbot of Marmoutier and nephew of Gregory IX,[22] was expelled by a popular uprising in 1375, and his fortification of Porta Sole was razed to the ground.[23]

Civic peace was constantly disturbed in the 14th century by struggles between the party representing the people (Raspanti) and the nobles (Beccherini). After the assassination in 1398 of Biordo Michelotti, who had made himself lord of Perugia, the city became a pawn in the Italian Wars, passing to Gian Galeazzo Visconti (1400), to Pope Boniface IX (1403), and to Ladislaus of Naples (1408–14) before it settled into a period of sound governance under the Signoria of the condottiero Braccio da Montone (1416–24), who reached a concordance with the Papacy. Following mutual atrocities of the Oddi and the Baglioni families, power was at last concentrated in the Baglioni, who, though they had no legal position, defied all other authority, though their bloody internal squabbles culminated in a massacre, 14 July 1500.[23] Gian Paolo Baglioni was lured to Rome in 1520 and beheaded by Leo X; and in 1540 Rodolfo, who had slain a papal legate, was defeated by Pier Luigi Farnese, and the city, captured and plundered by his soldiery, was deprived of its privileges. A citadel known as the Rocca Paolina, after the name of Pope Paul III, was built, to designs of Antonio da Sangallo the Younger "ad coercendam Perusinorum audaciam."[24]

In 1797, the city was conquered by French troops. On 4 February 1798, the Tiberina Republic was formed, with Perugia as capital, and the French tricolour as flag. In 1799, the Tiberina Republic merged to the Roman Republic.

In 1832, 1838 and 1854, Perugia was hit by earthquakes. Following the collapse of the Roman republic of 1848–49, when the Rocca was in part demolished,[23] it was seized in May 1849 by the Austrians. In June 1859 the inhabitants rebelled against the temporal authority of the Pope and established a provisional government, but the insurrection was quashed bloodily by Pius IX's troops.[25] In September 1860 the city was united finally, along with the rest of Umbria, as part of the Kingdom of Italy. During World War II the city suffered only some damage and was liberated by the British 8th army on 20 June 1944.[26]

Economy

Perugia has become famous for chocolate, mostly because of a single firm, Perugina, whose Baci ("kisses" in English) are widely exported.[27] Perugian chocolate is popular in Italy. The company's plant located in San Sisto (Perugia) is the largest of Nestlé's nine sites in Italy.[28] According to the Nestlé USA official website,[29] today Baci is the most famous chocolate brand in Italy.

The city hosts a chocolate festival every October.[30]

Geography

Perugia is the capital city of the region of Umbria. Cities' distances from Perugia: Assisi 19 kilometres (12 miles), Siena 102 km (63 miles), Florence 145 km (90 miles), Rome 164 km (102 miles).

Climate

Even though Perugia is located in the central part of Italy, the city experiences a humid subtropical climate (Köppen climate classification Cfa) similar to much of Northern Italy. Climate in this area has mild differences between highs and lows, and there is adequate rainfall year-round.[31]

| Climate data for Perugia (1971–2000, extremes 1967–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 17.3 (63.1) |

21.7 (71.1) |

25.6 (78.1) |

29.7 (85.5) |

35.0 (95.0) |

37.5 (99.5) |

39.6 (103.3) |

38.9 (102.0) |

35.3 (95.5) |

30.2 (86.4) |

24.0 (75.2) |

19.3 (66.7) |

39.6 (103.3) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 8.9 (48.0) |

10.9 (51.6) |

14.1 (57.4) |

16.8 (62.2) |

22.1 (71.8) |

26.1 (79.0) |

30.0 (86.0) |

30.0 (86.0) |

25.5 (77.9) |

19.7 (67.5) |

13.3 (55.9) |

9.3 (48.7) |

18.9 (66.0) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 4.8 (40.6) |

6.0 (42.8) |

8.4 (47.1) |

11.0 (51.8) |

15.7 (60.3) |

19.4 (66.9) |

22.6 (72.7) |

22.8 (73.0) |

19.2 (66.6) |

14.4 (57.9) |

8.9 (48.0) |

5.5 (41.9) |

13.2 (55.8) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 0.6 (33.1) |

1.1 (34.0) |

2.6 (36.7) |

5.1 (41.2) |

9.3 (48.7) |

12.6 (54.7) |

15.2 (59.4) |

15.6 (60.1) |

12.8 (55.0) |

9.1 (48.4) |

4.4 (39.9) |

1.8 (35.2) |

7.5 (45.5) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −15.8 (3.6) |

−17.0 (1.4) |

−8.3 (17.1) |

−5.0 (23.0) |

−1.9 (28.6) |

5.2 (41.4) |

6.9 (44.4) |

6.0 (42.8) |

3.6 (38.5) |

−1.4 (29.5) |

−8.2 (17.2) |

−14.8 (5.4) |

−17.0 (1.4) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 52.7 (2.07) |

56.8 (2.24) |

54.0 (2.13) |

72.0 (2.83) |

75.6 (2.98) |

69.9 (2.75) |

37.4 (1.47) |

49.7 (1.96) |

87.6 (3.45) |

85.7 (3.37) |

94.7 (3.73) |

68.4 (2.69) |

804.5 (31.67) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 7.1 | 7.1 | 7.0 | 8.7 | 8.4 | 7.1 | 4.7 | 4.9 | 6.5 | 7.7 | 8.4 | 7.8 | 85.4 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 83 | 77 | 73 | 74 | 74 | 71 | 68 | 69 | 71 | 76 | 82 | 85 | 75 |

| Source: Servizio Meteorologico (humidity 1968–1990)[32][33][34] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

In 2007, there were 163,287 people residing in Perugia, located in the province of Perugia, Umbria, of whom 47.7% were male and 52.3% were female. Minors (children ages 18 and younger) totalled 16.41 percent of the population compared to pensioners who number 21.51 percent. This compares with the Italian average of 18.06 percent (minors) and 19.94 percent (pensioners). The average age of Perugia residents is 44 compared to the Italian average of 42. In the five years between 2002 and 2007, the population of Perugia grew by 7.86 percent, while Italy as a whole grew by 3.85 percent.[35]

As of 2006, 90.84% of the population was Italian. The largest immigrant group came from other European countries (particularly from Albania and Romania): 3.93%, the Americas: 2.01%, and North African: 1.3%. The majority of inhabitants are Roman Catholic.

Education

Perugia today hosts two main universities, the ancient Università degli Studi (University of Perugia) and the Foreigners University (Università per Stranieri). Stranieri serves as an Italian language and culture school for students from all over the world.[36] Other educational institutions are the Perugia Fine Arts Academy "Pietro Vannucci" (founded in 1573), the Perugia Music Conservatory for the study of classical music, and the RAI Public Broadcasting School of Radio-Television Journalism.[37] The city is also host to the Umbra Institute, an accredited university program for American students studying abroad.[38] The Università dei Sapori (University of Tastes), a National centre for Vocational Education and Training in Food, is located in the city as well.[39]

Frazioni

The comune includes the frazioni of Bagnaia, Bosco, Capanne, Casa del Diavolo, Castel del Piano, Cenerente, Civitella Benazzone, Civitella d'Arna, Collestrada, Colle Umberto I, Cordigliano, Colombella, Farneto, Ferro di Cavallo, Fontignano, Fratticiola Selvatica, La Bruna, La Cinella, Lacugnano, Lidarno, Madonna Alta, Migiana di Monte Tezio, Monte Bagnolo, Monte Corneo, Montelaguardia, Monte Petriolo, Mugnano, Olmo, Parlesca, Pianello, Piccione, Pila, Pilonico Materno, Piscille, Ponte della Pietra, Poggio delle Corti, Ponte Felcino, Ponte Pattoli, Ponte Rio, Ponte San Giovanni, Ponte Valleceppi, Prepo, Pretola, Ramazzano-Le Pulci, Rancolfo, Ripa, Sant'Andrea delle Fratte, Sant'Egidio, Sant'Enea, San Fortunato della Collina, San Giovanni del Pantano, Sant'Andrea d'Agliano, Santa Lucia, San Marco, Santa Maria Rossa, San Martino dei Colli, San Martino in Campo, San Martino in Colle, San Sisto, Solfagnano, Villa Pitignano. Other localities are Boneggio, Canneto, Colle della Trinità, Monte Pulito, Montevile, Pieve di Campo, Montemalbe and Monte Morcino.

Collestrada, in the territory of the suburb of Ponte San Giovanni, saw a battle between the inhabitants of Perugia and Assisi in 1202.

Main sights

Churches

- Cathedral of S. Lorenzo

- San Pietro: late 16th-century church and abbey.

- San Domenico: Basilica church of the Dominican order, building began in 1394 and finished in 1458. Before 1234, this site housed markets and a horse fair. The exterior design attributed to Giovanni Pisano, while its interior redecorated in Baroque fashion by Carlo Maderno. The massive belfry was partially cut around the mid-16th century. The interior hosts the splendid tomb of Pope Benedict XI and a wooden choir from the Renaissance period.

- Sant'Angelo, also called San Michele Arcangelo: small paleo-Christian church from the 5th–6th centuries. Sixteen antique columns frame circular layout recalling the Roman church of Santo Stefano Rotondo.

- Sant'Antonio da Padova.

- San Bernardino: church with façade by Agostino di Duccio.

- San Ercolano: 14th-century church that resembles a polygonal tower. This church once had two floors. Its upper floor was demolished when the Rocca Paolina was built. Baroque interior decorations commissioned from 1607. The main altar has a sarcophagus found in 1609.

- Santa Giuliana: church and monastery founded by heir of a female monastery in 1253. In its later years, the church gained a reputation for dissoluteness. Later, the Napoleonic forces turned the church into a granary. Now, the church is a military hospital. The church, with a single nave, bears only traces of 13th century frescoes, which probably used to cover all of the walls. The cloister is a noteworthy example of mid-14th-century Cistercian architecture from Matteo Gattaponi. The upper part of the campanile is from the 13th-century.

- San Bevignate: church of the Templar.

Secular buildings

- The Palazzo dei Priori (Town Hall, encompassing the Collegio del Cambio, Collegio della Mercanzia, and Galleria Nazionale), one of Italy's greatest buildings.[40] The Collegio del Cambio has frescoes by Pietro Perugino, while the Collegio della Mercanzia has a fine later 14th century wooden interior.

- Galleria Nazionale dell'Umbria, the National Gallery of Umbrian art in Middle Ages and Renaissance (it includes works by Duccio, Piero della Francesca, Beato Angelico, Perugino)

- Fontana Maggiore, a medieval fountain designed by Fra Bevignate and sculpted by Nicola and Giovanni Pisano.

- Chapel of San Severo, which retains a fresco painted by Raphael[9] and Perugino.

- the Rocca Paolina, a Renaissance fortress (1540–1543) of which only a bastion today is remaining. The original design was by Antonio and Aristotile da Sangallo, and included the Porta Marzia (3rd century BC), the tower of Gentile Baglioni's house and a medieval cellar.

- Orto Botanico dell'Università di Perugia, the university's botanical garden

Antiquities

- the Ipogeo dei Volumni (Hypogeum of the Volumnus family), an Etruscan chamber tomb

- an Etruscan Well (Pozzo Etrusco).

- National Museum of Umbrian Archaeology, where one of the longest inscription in Etruscan is conserved, the so-called Cippus perusinus.

- Etruscan Arch (also known as Porta Augusta), an Etruscan gate with Roman elements.

Modern architecture

- Centro Direzionale (1982–1986), an administration civic center owned by the Umbria Region. The building was designed by the Pritzker Architecture prizewinner Aldo Rossi.[41]

Art

Perugia has had a rich tradition of art and artists. The High Renaissance painter Pietro Perugino created some of his masterpieces in the Perugia area. The other High Resaissance master Raphael was also active in Perugia and painted his famous Oddi Altar there in 1502–04.

Today, the Galleria Nazionale dell'Umbria in Perugia houses a number of masterpieces, including the Madonna with Child and six Angels, which represents the Renaissance Marian art of Duccio. And the private Art collection of Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Perugia has two separate locations.

The Collegio del Cambio is an extremely well preserved representation of a Renaissance building and houses a magnificent Pietro Perugino fresco.[42] The newly re-opened Academy of Fine Arts has a small but impressive plaster casts gallery and Perugian paintings and drawings from the 16th century on.[43]

Culture

- The Umbria Jazz Festival is one of the most important venues for Jazz in Europe and has been held annually since 1973, usually in July.[44]

- Sagra Musicale Umbra[45] is a classical and chamber music festival.

- The International Journalism Festival (Festival del Giornalismo).[46]

- Eurochocolate, chocolate festival and fair usually held in October each year.

- Music Fest Perugia, music festival for young talented musicians, usually in the summer.[47]

Umbria Jazz Festival 2008

International Journalism Festival 2009

Eurochocolate 2008

Notable people

- Trebonianus Gallus (206–253), Roman emperor

- Aaron the Bookseller, dealer in Hebrew and other ancient manuscripts

- Bartolo da Sassoferrato (1314–1357), medieval jurist

- Baldo degli Ubaldi (1327–1400), medieval guitarist

- Biordo Michelotti (1352–1398), condottiero

- Braccio da Montone (1368–1424), condottiero

- Matteo da Perugia (fl. 1390–1416), composer

- Niccolò Piccinino (1386–1444), condottiero

- Agostino di Duccio (ca. 1418–1481), sculptor

- Perugino (1450–1523), painter

- Pinturicchio (1454–1513), painter

- Giulio III (1487–1555), pope

- Galeazzo Alessi (1512–1572), architect

- Vincenzo Danti (1530–1576), sculpture and civil engineer

- Ignazio Danti (1536–1586), mathematician, cosmographer and bishop

- Giovanni Andrea Angelini Bontempi (1624–1705), composer

- Baldassarre Orsini (1732–1820), architect, academic and art historian

- Annibale Mariotti (1738–1801), physician and poet

- Francesco Morlacchi (1784–1841), composer

- Luisa Spagnoli (1877–1935), entrepreneur

- Gerardo Dottori (1884–1977), painter

- Gabriele Santini (1886–1964), orchestral conductor

- Giuseppe Prezzolini (1882–1982), writer

- Aldo Capitini (1899–1968), philosopher

- Sandro Penna (1906–1977), poet

- Walter Binni (1913–1997), literary critic

- Antonietta Stella (b. 1929), soprano

- Giovanni Mirabassi (b. 1970), jazz musician

- Walkiria Terradura (b. 1924), Partisan

Sport

A.C. Perugia Calcio is the main football club in the city, playing in Italy's second-highest division Serie B. The club plays at the 28,000-seat Stadio Renato Curi, named after a former player who died during a match. From 1983 to 2001, the stadium held four matches for the Italy national football team.[48]

Perugia has two water polo teams: L.R.N. Perugia and Gryphus. The team of LRN Perugia is currently in SERIE B ( second-highest division) and the Gryphus team is in the SERIE C (the third highest) division. The L.R.N Perugia has also a women's water polo team which is also playing in the division of SERIE B.

Sir Safety Umbria Volley, in English Sir Sicoma Colussi Perugia, is an Italian Volleyball club, playing at the top level of the Italian Volleyball League. They won their first Italian championship in 2018. Notable players include Luciano de Cecco of Argentina, Aleksandar Atanasijević of Serbia, and Wilfredo Leon of Poland.

The martial arts in Perugia have been present since the sixties with Chinese techniques, followed by judo. Later there were karate contact (later called kickboxing), karate, taijiquan, jūjutsu, kendo, aikido, taekwondo and, in recent years, krav maga has also arrived.

In 2014 Jessica Scricciolo, under the Ju-Jitsu Sports Group Perugia, won the title of World Champion in the Fighting System speciality, 55 kg. In March 2015 at the World Championship of Greece (J.J.I.F.) Andrea Calzon' (Ju-Jitsu Sports Group Perugia) won the gold medal in the Ne-Waza (U21.56 kg) and a bronze medal in the Fighting System.

Transport

An electric tramway operated in Perugia from 1901 until 1940. It was decommissioned in favour of buses, and since 1943 trolley buses – the latter were in service until 1975.

Two elevators were established since 1971:

- Mercato Coperto (Parking) – Terrazza Mercato Coperto

- Galleria Kennedy – Mercato Coperto (Pincetto)

This was followed by public escalators:

- Rocca Paolina: Piazza Partigiani – Piazza Italia (1983)

- Cupa-Pellini: Piazzale della Cupa – Via dei Priori (1989)

- Piazzale Europa – Piazzale Bellucci (1993)

- Piazzale Bellucci – Corso Cavour (1993)

- Minimetrò: Pincetto – Piazza Matteotti (2008)

Since 1971 Perugia has taken several measures against car traffic, when the first traffic restriction zone was implemented. These zones were expanded over time and at certain hours of the day driving is forbidden in the city centre. Large parking lots are provided in the lower town, from where the city can be reached via public transport.

Since 2008, an automated people mover called Minimetrò has also been in operation. It has seven stations, with one terminal at a large parking lot, and the other in the city centre.[49]

Perugia railway station, also known as Perugia Fontivegge, was opened in 1866. It forms part of the Foligno–Terontola railway, which also links Florence with Rome. The station is situated at Piazza Vittorio Veneto, in the heavily populated district of Fontivegge, about 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) southwest of the city centre.

Perugia San Francesco d'Assisi – Umbria International Airport is located 12 kilometres (7.5 mi) outside the city.

Twin towns — sister cities

Perugia is twinned with:[50]

References

- "Superficie di Comuni Province e Regioni italiane al 9 ottobre 2011". Istat. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- https://www.tuttitalia.it/umbria/provincia-di-perugia/72-comuni/popolazione/; Istat.

- "Perugia" (US) and "Perugia". Oxford Dictionaries UK Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- "Perugia". Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- "Perugia". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- cf. Perugia, Raffaele Rossi, Pietro Scarpellini, 1993 (Vol. 1, pg. 337, 344)

- "...it appears most probable that he did not enter Perugino's studio till the end of 1499, as during the four or five years before that Perugino was mostly absent from his native city. The so-called Sketch Book of Raphael in the academy of Venice contains studies apparently from the cartoons of some of Perugino's Sistine frescoes, possibly done as practice in drawing." (Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition).

See also "Perugia". The Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition. Columbia University Press., 2003 - The precise role of Raphael in Perugino's works, executed during his apprenticeship, is disputed by scholars. The independent works depicted in Perugia are: the Ansidei Madonna (taken by the French under the terms of the Treaty of Tolentino in 1798), the Deposition by Raphael (Pala Baglioni, this masterpiece was expropriated by Scipione Borghese in 1608, cf. 'The Guardian, October 19, 2004), the Madonna and Child Enthroned with Saints, by Raphael (formerly located in the convent of St Anthony of Padua cf.The Colonna Altarpiece review at Art History Archived 2007-12-19 at the Wayback Machine), the Connestabile Madonna (this picture left Perugia in 1871, when Count Connestabile sold it to the emperor of Russia for £13,200, cf. Encyclopædia Britannica), the Oddi altar by Raphael (requisitioned by the French in 1798)

- "...some studies for the figure of St. John the Martyr which Raphael used in 1505 in his great fresco in the Church of San Severo at Perugia." (The Notebooks of Leonardo Da Vinci (X)

- Perugia (2007). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved May 21, 2007, from Encyclopædia Britannica Online

- "How much of his glory is due to his kinsman, Fabius Pictor, the first historian of Rome, or to the family legends, which found in Etruria the most fitting scene for the exploits of the great Fabian house, we cannot tell" (Walter W. How and Henry Devenish Leigh, A History of Rome to the Death of Caesar London: Longmans, Green 1898:112).

- Livy ix.37.12).

- Livy ix.30.1–2, 31.1–3; indutiae with Volsinii, Perusia and Arretium, ix.37.4–5.

- cf. Corpus Inscr. Lat. xi. 1212

- Etruscan town walls.

- Latin inscriptions at two of the preserved Etruscan gates.

- Patrick Amory, People and Identity in Ostrogothic Italy, 489–554 pp185-86, referring to Perugia in passing, notes the increasingly localized role assumed since the mid-5th century by the bishops.

- Procopius, Bellum Gothicum, 3 (7).2.35.2, characteristically does not mention the incident, reported in Gregory the Great, Dialogues, 13 Archived 2009-09-17 at the Wayback Machine, who imagines a seven-year siege (i.e. since 540, before the accession of Baduila) and dramatically reports Herculanus' grotesque murder.

- Procopius of Caesarea, Gothic Wars I,16 and III,35.

- cf. Perugia, Raffaele Rossi, Attilio Bartoli Angeli, Roberta Sottani 1993 (Vol. 1, pp. 120–140)

- "Avvocato della Signoria cittadina e del Palazzo dei suoi Priori"

- Made a cardinal by his uncle, 20 December 1375 (Cardinals of the Holy Roman Church: 14th century)

- cf. Touring Club Italiano, Guida d'Italia: Umbria (1966)

- "in order to bring to heel the audacious Perugini".

- cf. Chicago Tribune, Jul 18, 1859 and "The outrage of the American witnesses in Perugia," Chicago Tribune, Jul 21, 1859

- "Advance to the Gothic Line". World War II Database. Retrieved 13 May 2014.

- Nestlè-Perugina produced in 2005 about 1.5 million Baci a day. Each October, Perugia has an annual chocolate festival called EuroChocolate. In Italy, right in the kisser, The Washington Post, May 29, 2005

- "European Industrial Relations Observatory, April 9, 2003". Eurofound.europa.eu. Archived from the original on October 10, 2013. Retrieved 2013-06-08.

- Archived September 29, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- Lehndorff, John; 471 words. "Thousands converge on historic city to celebrate everything chocolate Associated Press, October 21, 2002". Highbeam.com. Archived from the original on 2012-11-02. Retrieved 2013-06-08.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "Perugia, Italy Köppen Climate Classification (Weatherbase)". Weatherbase. Retrieved May 10, 2020.

- "Perugia/Sant'Egidio(PG)" (PDF). Atlante climatico. Servizio Meteorologico. Retrieved December 11, 2014.

- "STAZIONE 181 PERUGIA: medie mensili periodo 68–90" (in Italian). Servizio Meteorologico. Retrieved December 11, 2014.

- "Perugia Sant'Egidio: Record mensili dal 1967" (in Italian). Servizio Meteorologico dell’Aeronautica Militare. Retrieved December 11, 2014.

- "Statistiche demografiche ISTAT". Demo.istat.it. Retrieved 2009-05-06.

- BBC students diaries March 13, 2007

- See Perugia, University Town Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine and La Repubblica Università – Italian Journalism recognized schools (in Italian)

- "The Umbra Institute".

- See the institution educational purposes at the Università dei Sapori official site

- A short break in Perugia The Independent – London, June 6, 1999

- The Centro Direzionale is mentioned in the Aldo Rossi personal page at the Pritzker Prize official website Archived 2007-05-23 at the Wayback Machine

- "Collegio del Cambio". Travel.nytimes.com. The New York Times Company. Archived from the original on 16 July 2012. Retrieved 20 April 2010.

- "The Academy of Fine Arts of Perugia". Inperugia.com. 20 January 2013. Retrieved 20 January 2013.

- "Umbria Jazz".

- The Umbrian musical event is hosted in Perugia since the end of World War II NYT, October 18, 1953

- "International Journalism Festival".

- "Music Fest Perugia".

- http://eu-football.info/_venue.php?id=826

- "Perugia MiniMetro on". Urbanrail.net. 2008-01-29. Archived from the original on 2010-04-09. Retrieved 2010-04-20.

- "Città gemelle". turismo.comune.perugia.it (in Italian). Turismo Perugia. Retrieved 2019-12-16.

Bibliography

- Conestabile della Staffa, Giancarlo (1855). I Monumenti di Perugia etrusca e romana. Perugia.

- Gallenga Stuart, Romeo Adriano (1905). Perugia. Bergamo: Istituto italiano d'arti grafiche Editore.

- Heywood, William (1910). A history of Perugia. London: Methuen & Co.

- Mancini, Francesco Federico; Giovanna Casagrande. Perugia – guida storico-artistica. Perugia: Italcards. ISBN 88-7193-746-5.

- Rubin Blanshei, Sarah (1976). Perugia, 1260-1340: Conflict and Change in a Medieval Italian Urban Society. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society. ISBN 0-87169-662-2.

- Rossi, Raffaele; et al. (1993). Perugia. Milan: Elio Sellino Editore. ISBN 88-236-0051-0.

- Symonds, Margaret; Lina Duff Gordon (1898). The Story of Perugia. London: J.M. Dent & Co. ISBN 0-8115-0865-X.

- Zappelli, Maria Rita (2013). Zachary Nowak (ed.). Home Street Home: Perugia's History Told Through its Streets. Perugia: Morlacchi Editore. ISBN 978-88-6074-548-4.

Further reading

- Symonds, Margaret & Duff Gordon, Lina. The Story of Perugia.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Perugia. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Perugia. |

| Library resources about Perugia |

- Official website (in Italian)

- Official Perugia tourism website (in English, German, and Italian)

- ITALYscapes - Perugia