Penicillamine

Penicillamine, sold under the trade names of Cuprimine among others, is a medication primarily used for the treatment of Wilson's disease.[1] It is also used for people with kidney stones who have high urine cystine levels, rheumatoid arthritis, and various heavy metal poisonings.[1][2] It is taken by mouth.[2]

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Cuprimine, Cuprenyl, Depen, others |

| Other names | D-penicillamine |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a618021 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of administration | By mouth (capsules) |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | Variable |

| Metabolism | Liver |

| Elimination half-life | 1 hour |

| Excretion | Kidney |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.136 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C5H11NO2S |

| Molar mass | 149.21 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Common side effects include rash, loss of appetite, nausea, diarrhea, and low blood white blood cell levels.[1] Other serious side effects include liver problems, obliterative bronchiolitis, and myasthenia gravis.[1] It is not recommended in people with lupus erythematosus.[2] Use during pregnancy may result in harm to the baby.[2] Penicillamine works by binding heavy metals; the resulting penicillamine–metal complexes are then removed from the body in the urine.[1]

Penicillamine was approved for medical use in the United States in 1970.[1] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[3]

Medical uses

It is used as a chelating agent:

- In Wilson's disease, a rare genetic disorder of copper metabolism, penicillamine treatment relies on its binding to accumulated copper and elimination through urine.[4]

- Penicillamine was the second line treatment for arsenic poisoning, after dimercaprol (BAL).[5] It is no longer recommended.[6]

In cystinuria, a hereditary disorder in which high urine cystine levels lead to the formation of cystine stones, penicillamine binds with cysteine to yield a mixed disulfide which is more soluble than cystine.[7]

Penicillamine has been used to treat scleroderma.[8]

Penicillamine can be used as a disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD) to treat severe active rheumatoid arthritis in patients who have failed to respond to an adequate trial of conventional therapy,[9] although it is rarely used today due to availability of TNF inhibitors and other agents, such as tocilizumab and tofacitinib. Penicillamine works by reducing numbers of T-lymphocytes, inhibiting macrophage function, decreasing IL-1, decreasing rheumatoid factor, and preventing collagen from cross-linking.

Adverse effects

Bone marrow suppression, dysgeusia, anorexia, vomiting and diarrhea are the most common side effects, occurring in ~20–30% of the patients treated with penicillamine.[10][11]

Other possible adverse effects include:

- Nephropathy[7][10]

- Hepatotoxicity[12]

- Membranous glomerulonephritis[13]

- Aplastic anemia (idiosyncratic)[12]

- Antibody-mediated myasthenia gravis[10] and Lambert–Eaton myasthenic syndrome, which may persist even after its withdrawal

- Drug-induced systemic lupus erythematosus[14]

- Elastosis perforans serpiginosa[15]

- Toxic myopathies[16]

- Unwanted breast growth[17]

Chemistry

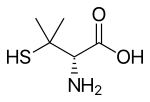

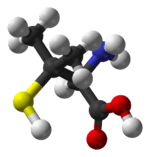

Penicillamine is a trifunctional organic compound, consisting of a thiol, an amine, and a carboxylic acid. It is structurally similar to the α-amino acid cysteine, but with geminal dimethyl substituents α to the thiol. Like most amino acids, it is a colorless solid that exists in the zwitterionic form at physiological pH. Of its two enantiomers, L-penicillamine (having R absolute configuration) is toxic because it inhibits the action of pyridoxine (also known as vitamin B6).[18] That enantiomer is a metabolite of penicillin but has no antibiotic properties itself.[19] A variety of penicillamine–copper complex structures are known.[20]

History

John Walshe first described the use of penicillamine in Wilson's disease in 1956.[21] He had discovered the compound in the urine of patients (including himself) who had taken penicillin, and experimentally confirmed that it increased urinary copper excretion by chelation. He had initial difficulty convincing several world experts of the time (Denny Brown and Cumings) of its efficacy, as they held that Wilson's disease was not primarily a problem of copper homeostasis but of amino acid metabolism, and that dimercaprol should be used as a chelator. Later studies confirmed both the copper-centered theory and the efficacy of D-penicillamine. Walshe also pioneered other chelators in Wilson's such as triethylene tetramine dihydrochloride and tetrathiomolybdate.[22]

Penicillamine was first synthesized by John Cornforth (Somerville College, Oxford) under supervision of Robert Robinson.[23]

Penicillamine has been used in rheumatoid arthritis since the first successful case in 1964.[24]

Cost

In the United States, Valeant raised the cost of the medication from about US$500 to US$24,000 per month in 2016.[25]

References

- "Penicillamine". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 21 December 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- World Health Organization (2009). Stuart MC, Kouimtzi M, Hill SR (eds.). WHO Model Formulary 2008. pp. 64, 592. hdl:10665/44053. ISBN 9789241547659.

- World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- Peisach, J.; Blumberg, W. E. (1969). "A mechanism for the action of penicillamine in the treatment of Wilson's disease". Molecular Pharmacology. 5 (2): 200–209. PMID 4306792.

- Peterson, R. G.; Rumack, B. H. (1977). "D-Penicillamine therapy of acute arsenic poisoning". The Journal of Pediatrics. 91 (4): 661–666. doi:10.1016/S0022-3476(77)80528-3. PMID 908992.

- Hall, A. H. (2002). "Chronic arsenic poisoning". Toxicology Letters. 128 (1–3): 69–72. doi:10.1016/S0378-4274(01)00534-3. PMID 11869818.

- Rosenberg, L. E.; Hayslett, J. P. (1967). "Nephrotoxic Effects of Penicillamine in Cystinuria". JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 201 (9): 698. doi:10.1001/jama.1967.03130090062021.

- Steen, V. D.; Medsger Jr, T. A.; Rodnan, G. P. (1982). "D-Penicillamine therapy in progressive systemic sclerosis (scleroderma): A retrospective analysis". Annals of Internal Medicine. 97 (5): 652–659. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-97-5-652. PMID 7137731.

- "Cuprimine (penicillamine) Capsules for Oral Use. U.S. Full Prescribing Information" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 September 2015. Retrieved 29 April 2016.

- Camp, A. V. (1977). "Penicillamine in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis". Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine. 70 (2): 67–69. doi:10.1177/003591577707000201. PMC 1542978. PMID 859814.

- Grasedyck, K. (1988). "D-Penicillamine—side effects, pathogenesis and decreasing the risks". Zeitschrift für Rheumatologie. 47 Suppl 1: 17–19. PMID 3063003.

- Fishel, B.; Tishler, M.; Caspi, D.; Yaron, M. (1989). "Fatal aplastic anaemia and liver toxicity caused by D-penicillamine treatment of rheumatoid arthritis". Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 48 (7): 609–610. doi:10.1136/ard.48.7.609. PMC 1003826. PMID 2774703.

- Mitchell, Richard Sheppard; Kumar, Vinay; Abbas, Abul K.; Fausto, Nelson (2007). "Table 14-2". Robbins Basic Pathology (8th ed.). Philadelphia: Saunders. ISBN 978-1-4160-2973-1.

- Chalmers, A.; Thompson, D.; Stein, H. E.; Reid, G.; Patterson, A. C. (1982). "Systemic lupus erythematosus during penicillamine therapy for rheumatoid arthritis". Annals of Internal Medicine. 97 (5): 659–663. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-97-5-659. PMID 6958210.

- Bolognia, Jean; et al. (2007). Dermatology. Philadelphia: Elsevier. ISBN 978-1-4160-2999-1.2nd edition.

- Underwood, J. C. E. (2009). General and Systemic Pathology. Elsevier Limited. ISBN 978-0-443-06889-8.

- Taylor; Cumming; Corenblum (31 January 1981). "Successful treatment of D-penicillamine-induced breast gigantism with danazol". Br Med J. 282 (6261): 362–3. doi:10.1136/bmj.282.6261.362-a. PMC 1504185. PMID 6780026.

- Aronson, J. K. (2010). Meyler's Side Effects of Analgesics and Anti-inflammatory Drugs. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science. p. 613. ISBN 9780080932941. Archived from the original on 10 September 2017.

- Parker, C. W.; Shapiro, J.; Kern, M.; Eisen, H. N. (1962). "Hypersensitivity to penicillenic acid derivatives in human beings with penicillin allergy". The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 115 (4): 821–838. doi:10.1084/jem.115.4.821. PMC 2137514. PMID 14483916.

- Birker, Paul J. M. W. L.; Freeman, Hans C. (1977). "Structure, properties, and function of a copper(I)–copper(II) complex of D-penicillamine: pentathallium(I) μ8-chloro-dodeca(D-penicillaminato)octacuprate(I)hexacuprate(II) n-hydrate". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 99 (21): 6890–6899. doi:10.1021/ja00463a019. PMID 903530.

- Walshe, J. M. (January 1956). "Wilson's disease; new oral therapy". Lancet. 270 (6906): 25–6. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(56)91859-1. PMID 13279157.

- Walshe, J. M. (August 2003). "The story of penicillamine: a difficult birth". Mov. Disord. 18 (8): 853–9. doi:10.1002/mds.10458. PMID 12889074.

- Oakes, Elizabeth H. (2007). Encyclopedia of World Scientists. Infobase Publishing. p. 156. ISBN 9781438118826.

- Jaffe, I. A. (1964). "Rheumatoid Arthritis with Arteritis; Report of a Case Treated with Penicillamine". Annals of Internal Medicine. 61: 556–563. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-61-3-556. PMID 14218939.

- Petersen, Melody. "How 4 drug companies rapidly raised prices on life-saving drugs". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 27 March 2019.

External links

- "Penicillamine". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.