Bosom of Abraham

"Bosom of Abraham" refers to the place of comfort in the Biblical Sheol (or Hades in the Greek Septuagint version of the Hebrew scriptures from around 200 BC, and therefore so described in the New Testament)[1] where the righteous dead await Judgment Day.

.jpg)

The phrase and concept are found in both Judaism and Christian religions and religious art, but is not found in Islam.

Origin of the phrase

The word found in the Greek text for "bosom" is kolpos, meaning "lap" "bay".[2] This relates to the Second Temple period practice of reclining and eating meals in proximity to other guests, the closest of whom physically was said to lie on the bosom (chest) of the host. (See John 13:23 )[3][4]

While commentators generally agree upon the meaning of the "Bosom of Abraham", they disagree about its origins. Up to the time of Maldonatus (AD 1583), its origin was traced back to the universal custom of parents to take up into their arms, or place upon their knees, their children when they are fatigued, or return home, and to make them rest by their side during the night (cf. 2 Samuel 12:3;[5] 1 Kings 3:20; 17:19; Luke 11:7 sqq.), thus causing them to enjoy rest and security in the bosom of a loving parent. After the same manner was Abraham supposed to act towards his children after the fatigues and troubles of the present life, hence the metaphorical expression "to be in Abraham's Bosom" as meaning to be in repose and happiness with him.

According to Maldonatus (1583),[6] whose theory has since been accepted by many scholars, the metaphor "to be in Abraham's Bosom" is derived from the custom of reclining on couches at table, which prevailed among the Jews during and before the time of Jesus. As at a feast each guest leaned on his left elbow so as to leave his right arm at liberty, and as two or more lay on the same couch, the head of one man was near the breast of the man who lay behind, and he was therefore said "to lie in the bosom" of the other.

It was also considered by the Jews of old a mark of special honour and favour for one to be allowed to lie in the bosom of the master of the feast (cf. John 13:23), and it is by this illustration that they pictured the next world. They conceived of the reward of the righteous dead as a sharing in a banquet given by Abraham, "the father of the faithful" (cf. Matthew 8:11 sqq.), and of the highest form of that reward as lying in "Abraham's Bosom".

Abode of the righteous dead

Judaism

In First Temple Judaism, Sheol in the Hebrew Old Testament, or Hades in the Septuagint, is primarily a place of "silence" to which all humans go. However, during, or before, the exile in Babylon ideas of activity of the dead in Sheol began to enter Judaism.[7][8]

During the Second Temple period (roughly 500 BCE–70 CE) the concept of a Bosom of Abraham first occurs in Jewish papyri that refer to the "Bosom of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob".[9] This reflects the belief of Jewish martyrs who died expecting that: "after our death in this fashion Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob will receive us and all our forefathers will praise us" (4 Maccabees 13:17).[10] Other early Jewish works adapt the Greek mythical picture of Hades to identify the righteous dead as being separated from unrighteous in the fires by a river or chasm. In the pseudepigraphical Apocalypse of Zephaniah the river has a ferryman equivalent to Charon in Greek myth, but replaced by an angel. On the other side in the Bosom of Abraham : "You have escaped from the Abyss and Hades, now you will cross over the crossing place... to all the righteous ones, namely Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, Enoch, Elijah and David."[11] In this story Abraham was not idle in the Bosom of Abraham, he acted as intercessor for those in the fiery part of Hades.[12]

The pseudepigraphic Book of Enoch describes travels through the cosmos and divides Sheol into four sections: for the truly righteous, the good, the wicked who are punished till they are released at the resurrection, and the wicked that are complete in their transgressions and who will not even be granted mercy at the resurrection. However, since the book is pseudepigraphic to the hand of Enoch, who predates Abraham, naturally the character of Abraham does not feature.

Later rabbinical sources preserve several traces of the Bosom of Abraham teaching.[13][14] In Kiddushin 72b, Adda bar Ahavah of the third century, is said to be "sitting in the bosom of Abraham", Likewise "In the world to come Abraham sits at the gate of Gehenna, permitting none to enter who bears the seal of the covenant" according to Rabbi Levi in Genesis Rabba 67.[15] In the 1860s Abraham Geiger suggested that the parable of Lazarus in Luke 16 preserved a Jewish legend and that Lazarus represented Abraham's servant Eliezer[16]

New Testament

The phrase bosom of Abraham occurs only once in the New Testament, in the parable of the rich man and Lazarus in the gospel of Luke (Luke 16:22). Leprous Lazarus is carried by the angels to that destination after death. Abraham's bosom contrasts with the destination of a rich man who ends up in Hades (see Luke 16:19-31). The account corresponds closely with documented 1st century AD Jewish beliefs (see above), that the dead were gathered into a general tarrying-place, made equivalent with the Sheol of the Old Testament. In Christ's account, the righteous occupied an abode of their own, which was distinctly separated by a chasm from the abode to which the wicked were consigned. The chasm is equivalent to the river in the Jewish version, but in Christ's version there is no angelic ferryman, and it is impossible to pass from one side to the other.

The fiery part of Hades (Hebrew Sheol) is distinguished from the separate Old Testament, New Testament and Mishnah concept of Gehenna (Hebrew Hinnom), which is generally connected with the Last Judgment. Matthew 5:29–30; 18:9ff, Mark 9:42.[17]

The concept of paradise is not mentioned in Luke 16, nor are any of the distinguishing Jewish associations of paradise such as Third Heaven (found with "paradise" in 2 Corinthians 12:2–4 and Apocalypse of Moses), or the tree of life (found with "paradise" in Genesis 2:8 Septuagint and Book of Revelation 2:7).[18] Consequently, identification of Bosom of Abraham with Paradise is contested.[19] It is not clear whether Matthew 8:11 "And I tell you that many will come from the East and West and will eat with Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob in the kingdom of heaven." represents an alternative or complementary cosmology to the ideas of Luke 16:19–31.[20]

Early Christianity

In the 3rd century, Hippolytus of Rome referred to Abraham's bosom as the place in hades where the righteous await judgment day in delight.[21] Due to a copying error a loose section of Hippolytus' commentary on Luke 16 was misidentified as a Discourse to the Greeks on Hades by Josephus and included in William Whiston's translation of the Complete Works of Josephus.[22]

Augustine of Hippo likewise referred to the righteous dead as disembodied spirits blissfully awaiting Judgment Day in secret receptacles.[23]

Since the righteous dead are rewarded in the bosom of Abraham before Judgment Day, this belief represents a form of particular judgment.

Abraham's bosom is also mentioned in the Penitence of Origen of uncertain date and authorship.

Relation to Christian heaven

Among Christian writers, since the 1st century AD, "the Bosom of Abraham" has gradually ceased to designate a place of imperfect happiness, especially in the Western Catholic tradition, and it has generally become synonymous with Christian Heaven itself, or the Intermediate state. Church fathers sometimes used the term to mean the limbo of the fathers, the abode of the righteous who died before Christ and who were not admitted to heaven until his resurrection. Sometimes they mean Heaven, into which the just of the New Covenant are immediately introduced upon their demise. Tertullian, on the other hand, described the bosom of Abraham as that section of Hades in which the righteous dead await the day of the Lord.[24]

When Christians pray that the angels may carry the soul of the departed to "Abraham's Bosom", non-Orthodox Christians might mean it as heaven; as it is taught in the West that those in the Limbo of the Fathers went to heaven after the Ascension of Jesus, and so Abraham himself is now in heaven. However, the understanding of both Eastern Orthodoxy and Oriental Orthodoxy preserves the Bosom of Abraham as distinct from heaven.[25]

The belief that the souls of the dead go immediately to hell, heaven, or purgatory is a Western Christian teaching. That is rejected and in contrast to the Eastern Christian concept of the Bosom of Abraham.[25]

Martin Luther considered the parable allegorical. Christian mortalism, especially prevalent among Seventh-day Adventists, is the belief that the dead, righteous and unrighteous, rest unconsciously while awaiting the Judgment.

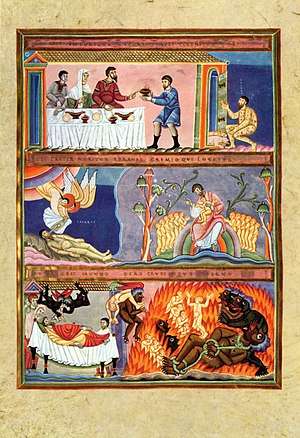

In Christian art

In medieval Christian art the phase was illustrated literally: images of a number of miniature figures, representing souls, held on the lap of a much larger one occur in a number of contexts. Many Gothic cathedrals, especially in France, have reliefs of Abraham holding such a group (right), which are also found in other media. In a detached miniature of about 1150, from a work of Hildegard of Bingen, a figure usually described as "Synagogue", of youngish appearance with closed eyes, holds a group, here of Jewish souls, with Moses carrying the Tablets above the others, held in the large figure's folded arms.[26] In the Bosom of Abraham Trinity, a subject only found in medieval English art, God the Father holds the group, now representing specifically Christian souls. The Virgin of Mercy is a different but somewhat similar image.

In literature

- In William Shakespeare's play Henry V, after the death of Sir John Falstaff, Mistress Quickly asserts confidently that "He's in Arthur's bosom, if ever man went to Arthur's bosom." Quickly, an uneducated innkeeper, has presumably confused the Christian idea of Abraham's bosom with the legend of King Arthur.

- In William Wordsworth's poem "It is a beauteous evening, calm and free", Wordsworth writes about a walk on the beach with his daughter Caroline, who lived in France with her mother and whom he saw only rarely. A line from the poem reads, "Thou liest in Abraham's bosom all the year"—a double meaning, in that to Wordsworth she is righteous and blissful, and also that she "liest" in her father's heart all the time, even when they are apart.

References

Citations

- Longenecker, Richard N. (2003). "Cosmology". In Gowan, Donald E. (ed.). The Westminster Theological Wordbook of the Bible. Westminster John Knox Press. p. 189.

- The Septuagint Greek version of Isaiah 40:11 uses another Greek word: γαστρι

- Jhn 13:23 Now there was leaning on Jesus' bosom one of his disciples, whom Jesus loved.

- Jhn 1:18 No man hath seen God at any time; the only begotten Son, which is in the bosom of the Father, he hath declared [him].

- Septuagint ἐν τῷ κόλπῳ αὐτοῦ

- In Lucam, xvi, 22

- Gen. 37:36, Ps. 88:13, Ps. 154:17; Eccl. 9:10 etc.

- Jewish Encyclopedia "Sheol"

- F. Preisigke, Sammelbuch Griechischer Urkunden aus Aegypten (Scrapbook Greek documents from Egypt) 2034:11

- James H. Charlesworth (1983). "4 Maccabees 13:7". The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha. Doubleday. ISBN 0385096305.

- James H. Charlesworth (1983). "Apoc. Zeph. 9:2". The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha. Doubleday. ISBN 0385096305.

- Apoc. Zeph. 11:1–2

- John Lightfoot Horae Hebraicae et Talmudicae 1671

- Louis Ginzberg, Legends of the Jews 1909

- "Bosom of Abraham" in Jewish Encyclopedia 1904

- Jüdische Zeitschrift für Wissenschaft und Leben Vol.VII 200. 1869

- "Gehenna": in Freedman, David Noel, ed., The Anchor Bible Dictionary, New York Doubleday 1997

- "Paradise": in Freedman, David Noel, ed., The Anchor Bible Dictionary, New York Doubleday 1997

- Fitzmyer, Joseph A. The Gospel According to Luke X–XXIV The Anchor Yale Bible Commentaries Volume 28A

- Nolland J. Luke 9:21–18:34, Word Biblical Commentary Vol. 35b, 1993

- Hippolytus of Rome, Against Plato, on the Cause of the Universe, §1. As to the state of the righteous, he writes, "And there the righteous from the beginning dwell, not ruled by necessity, but enjoying always the contemplation of the blessings which are in their view, and delighting themselves with the expectation of others ever new, and deeming those ever better than these. And that place brings no toils to them. There, there is neither fierce heat, nor cold, nor thorn; but the face of the fathers and the righteous is seen to be always smiling, as they wait for the rest and eternal revival in heaven which succeed this location. And we call it by the name Abraham's bosom." Ibid.

- Josephus, Flavius; Whiston, William (1841). The works of Flavius Josephus, the learned and authentic Jewish historian. Simms and Mʻintyre. p. 824.

- Augustine of Hippo, City of God, Book XII

- Tertullian, A Treatise on the Soul, Chapter 7.

- Life After Death Archived 2009-02-19 at the Wayback Machine by Metropolitan Hierotheos

- Dodwell, C. R.; The Pictorial arts of the West, 800–1200, p. 282 (with illustration), 1993, Yale UP, ISBN 0-300-06493-4

Other sources

External links

- Abraham's Bosom in the Jewish Encyclopedia.