Pathé

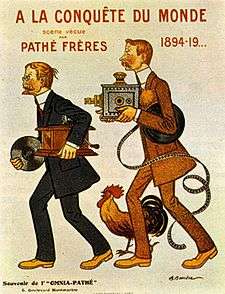

Pathé or Pathé Frères (French pronunciation: [pate fʁɛʁ], styled as PATHÉ!) is the name of various French businesses that were founded and originally run by the Pathé Brothers of France starting in 1896. In the early 1900s, Pathé became the world's largest film equipment and production company, as well as a major producer of phonograph records. In 1908, Pathé invented the newsreel that was shown in cinemas before a feature film.[2]

Pathé's current logo | |

| Industry | Entertainment |

|---|---|

| Founded | 28 September 1896 |

| Founder | Charles Pathé |

| Headquarters | , |

| Revenue | |

| Owner | Jérôme Seydoux Eduardo Malone |

Number of employees | 4,210 (2017)[1] |

| Subsidiaries | Les Cinémas Gaumont Pathé |

| Website | www |

Pathé is a major film production and distribution company, owning a number of cinema chains through its subsidiary Les Cinémas Gaumont Pathé and television networks across Europe. It is the second oldest operating film company behind Gaumont Film Company which was established in 1895.

History

The company was founded as Société Pathé Frères (Pathé Brothers Company) in Paris, France on 28 September 1896, by the four brothers Charles, Émile, Théophile and Jacques Pathé.[3] During the first part of the 20th century, Pathé became the largest film equipment and production company in the world, as well as a major producer of phonograph records.

Pathé Records

The driving force behind the film operation and phonograph business was Charles Pathé, who had helped open a phonograph shop in 1894 and established a phonograph factory at Chatou on the western outskirts of Paris. The Pathé brothers began selling Edison and Columbia phonographs and accompanying cylinder records and later, the brothers designed and sold their own phonographs that incorporated elements of other brands.[4] Soon after, they also started marketing pre-recorded cylinder records. By 1896 the Pathé brothers had offices and recording studios not only in Paris, but also in London, Milan, and St. Petersburg. Pathé manufactured cylinder records until approximately 1914. In 1905[5] the Pathé brothers entered the growing field of disc records.[6]

In France, Pathé became the largest and most successful distributor of cylinder records and phonographs. These, however, failed to make significant headway in foreign markets such as the United Kingdom and the United States where other brands were already in widespread use.[7]

In December 1928, the French and British Pathé phonograph assets were sold to the British Columbia Graphophone Company. In July 1929, the assets of the American Pathé record company were merged into the newly formed American Record Corporation.[5] The Pathé and Pathé-Marconi labels and catalogue still survive, first as imprints of EMI and now currently EMI's successor Parlophone Records.

Pathé films

As the phonograph business became successful, Pathé saw the opportunities offered by new means of entertainment and in particular by the fledgling motion picture industry. Having decided to expand the record business to include film equipment, the company expanded dramatically. To finance its growth, the company took the name Compagnie Générale des Établissements Pathé Frères Phonographes & Cinématographes (sometimes abbreviated as "C.G.P.C.") in 1897, and its shares were listed on the Paris Stock Exchange.[8] In 1896, Mitchell Mark of Buffalo, New York, became the first American to import Pathé films to the United States, where they were shown in the Vitascope Theater.[9]

In 1907, Pathé acquired the Lumière brothers' patents and then set about to design an improved studio camera and to make their own film stock. Their technologically advanced equipment, new processing facilities built at Vincennes, and aggressive merchandising combined with efficient distribution systems allowed them to capture a huge share of the international market. They first expanded to London in 1902 where they set up production facilities and a chain of movie theatres.[10]

By 1909, Pathé had built more than 200 movie theatres in France and Belgium and by the following year they had facilities in Madrid, Moscow, Rome and New York City plus Australia and Japan. Slightly later, they opened a film exchange in Buffalo, New York.[11] Through its American subsidiary, it was part of the MPCC cartel of production in the United States. It participated in the Paris Film Congress in February 1909 as part of a plan to create a similar European organisation. The company withdrew from the project in a second meeting in April which fatally undermined the proposal.

Prior to the outbreak of World War I, Pathé dominated Europe's market in motion picture cameras and projectors. It has been estimated[12] that at one time, 60 percent of all films were shot with Pathé equipment. In 1908, Pathé distributed Excursion to the Moon by Segundo de Chomón, an imitation of Georges Méliès's A Trip to the Moon. Pathé and Méliès worked together in 1911. Georges Méliès made a film Baron Munchausen's Dream, his first film to be distributed by Pathé. Pathé's relationship with Méliès soured, and in 1913 Méliès went bankrupt, and his last film was never released by Pathé.[13]

Innovations

Worldwide, the company emphasised research, investing in such experiments as hand-coloured film and the synchronisation of film and gramophone recordings. In 1908, Pathé invented the newsreel that was shown in theatres prior to the feature film. The news clips featured the Pathé logo of a crowing rooster at the beginning of each reel. In 1912, it introduced 28 mm non-flammable film and equipment under the brand name Pathescope. Pathé News produced cinema newsreels from 1910, up until the 1970s when production ceased as a result of mass television ownership.[14]

In the United States, beginning in 1914, the company's film production studios in Fort Lee and Jersey City, NJ, where their building still stands. The Heights, Jersey City produced the extremely successful serialised episodes called The Perils of Pauline. By 1918 Pathé had grown to the point where it was necessary to separate operations into two distinct divisions. With Emile Pathé as chief executive, Pathé Records dealt exclusively with phonographs and recordings while brother Charles managed Pathé-Cinéma which was responsible for film production, distribution, and exhibition.[15]

1922 saw the introduction of the Pathé Baby home film system using a new 9.5 mm film stock which became popular over the next few decades. In 1921, Pathé sold off its United States motion picture production arm, which was renamed "Pathé Exchange" and later merged into RKO Pictures, disappearing as an independent brand in 1931. Pathé sold its British film studios to Eastman Kodak in 1927 while maintaining the theatre and distribution arm.[16]

Natan to Parretti

Pathé was already in substantial financial trouble when Bernard Natan took control of the company in 1929. Studio founder Charles Pathé had been selling assets for several years to boost investor value and keep the studio's cash flow healthy. The company's founder had even sold Pathé's name and "rooster" trademark to other companies in return for a mere 2 percent of revenues. Natan had the bad luck to take charge of the studio just as the Great Depression convulsed the French economy.[17][18]

Natan attempted to steady Pathé's finances and implement modern film industry practices at the studio. Natan acquired another film studio, Société des Cinéromans, from Arthur Bernède and Gaston Leroux, which enabled Pathé to expand into projector and electronics manufacturing. He also bought the Fornier chain of motion picture theatres and rapidly expanded the chain's nationwide presence.[17][18][19] The French press, however, attacked Natan mercilessly for his stewardship of Pathé. Many of these attacks were antisemitic.[20]

Pathé-Natan did well under Natan's guidance. Between 1930 and 1935, despite the world economic crisis, the company made 100 million francs in profits, and produced and released more than 60 feature films (just as many films as major American studios produced at the time). He resumed production of the newsreel Pathé News, which had not been produced since 1927.[17]

Natan also invested heavily into research and development to expand Pathé's film business. In 1929, he pushed Pathé into sound film. In September, the studio produced its first sound feature film, and its first sound newsreel a month later. Natan also launched two new cinema-related magazines, Pathé-Revue and Actualités Féminines, to help market Pathé's films and build consumer demand for cinema. Under Natan, Pathé also funded the research of Henri Chrétien, who developed the anamorphic lens (leading to the creation of CinemaScope and other widescreen film formats common today).[18][19]

Natan expanded Pathé's business interests into communications industries other than film. In November 1929, Natan established France's first television company, Télévision-Baird-Natan. A year later, he purchased a radio station in Paris and formed a holding company (Radio-Natan-Vitus) to run what would become a burgeoning radio empire.[17][18][19]

But in 1935, Pathé went bankrupt. In order to finance the company's continued expansion, Pathé's board of directors (which still included Charles Pathé) voted in 1930 to issue shares worth 105 million francs. But with the depression deepening, only 50 percent of the shares were purchased. One of the investor banks collapsed due to financial difficulties unrelated to Pathé's problems, and Pathé was forced to follow through with the purchase of several movie theatre chains it no longer could afford to buy. Although the company continued to make a profit (as noted above), it lost more money than it could bring in.[18][19]

The collapse of Pathé led French authorities to indict Bernard Natan on charges of fraud. Natan was accused of financing the purchase of the company without any collateral, of bilking investors by establishing fictitious shell corporations, and negligent financial mismanagement. Natan was even accused of hiding his Romanian and Jewish heritage by changing his name. Natan was indicted and imprisoned in 1939. A second indictment was brought in 1941, and he was convicted shortly thereafter. He was removed from prison by the French authorities in September 1942, delivered to the Nazis, and deported to Auschwitz where he died in October 1942.[17][18][19]

The company was forced to undergo a restructuring in 1943 and was acquired by Adrien Ramauge.[21] Over the years, the business underwent a number of changes including diversification into producing programmes for the burgeoning television industry. During the 1970s, operating theatres overtook film production as Pathé's primary source of revenue.

In the late 1980s, Italian financier Giancarlo Parretti tried to make a bid for Pathé, even taking over Cannon and renaming it Pathé Communications in anticipation of owning the storied studio. Parretti's shady past, however, raised enough eyebrows in the French government that the deal fell through. It turned out to be a fortunate decision, as Parretti later took over Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, and merged it with his Pathé Communications Group to create MGM-Pathé Communications in 1990, only to lose it in bankruptcy in late 1991.

Jérôme Seydoux

In 1990 Chargeurs, a French conglomerate led by Jérôme Seydoux, took control of the company.[22] As a result of the deregulation of the French telecommunications market, in June 1999, Pathé merged with Vivendi, the exchange ratio for the merger fixed at three Vivendi shares for every two Pathé shares. The Wall Street Journal estimated the value of the deal at US$2.59 billion. Following the completion of the merger, Vivendi retained Pathé's interests in British Sky Broadcasting and CanalSatellite, a French broadcasting corporation,[23] but then sold all remaining assets to Jérôme Seydoux's family-owned corporation, Fornier SA, which changed its name to Pathé.

Sectors

The sectors in which Pathé operates today are:

Cinema

Television

At the beginning of the 2000s, Pathé owned several generalist or thematic French television channels. These channels would eventually be sold to other companies:

- Comédie+: In 2003, Pathé bought the entire channel and sold it to the Canal+ Group (via MultiThématiques) at the end of 2004.

- Cuisine.tv: Pathé created the channel with RF2K in 2001 and sold it in 2011 to the Canal+ Group (via MultiThématiques).

- Histoire: During the creation of the channel in 1997, Pathé owned 30% of the channel. It sold their stake at the end of 2004 to the TF1 Group.

- Pathé Sport: In 1998, Pathé bought the AB Sports channel belonging to the AB Groupe and renamed it. It was sold in 2002 to Canal+ Group to become Sport+.

- TMC: In 2002, Pathé bought an 80% stake on the Canal+ Group and sold them in 2004 to TF1 Group and AB Groupe.

- Voyage: Pathé bought the channel in May 1997 and sold it in 2004 to Fox International Channels.

International distribution

In its home country France, Pathé self-distributes its films through Pathé Distribution (formerly called AMLF from 1972 to 1998). On home video, their films are distributed by Fox Pathé Europa, a joint venture between 20th Century Fox, Pathé and EuropaCorp.

Since 2020 in the United Kingdom, Walt Disney Studios Home Entertainment currently distributes Pathé's material on home video. Previously, 20th Century Fox Home Entertainment distributed Pathé's material from the 1990s until 2020. For theatrical releases, Pathé formerly distributed their releases through Guild Film Distribution, renamed to Guild Pathé Cinema when the company purchased Guild in 1996, which then became the British branch of Pathé Distribution in 1999. In 2009, Warner Bros. began to distribute Pathé's material theatrically, until the rights were transferred over to Fox in February 2011.[26] After The Walt Disney Company's purchase of 20th Century Fox, Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures took over distributing Pathé's material in the UK.

Films

1980's

- The Apple (France distribution only)

- The Cook, the Thief, His Wife & Her Lover (France distribution only)

- Felix the Cat: The Movie (France distribution only)

- Halloween 4: The Return of Michael Myers (France distribution only)

- Halloween 5: The Revenge of Michael Myers (France distribution only)

- Highlander (France distribution only)

- Kickboxer (France distribution only)

- Pirates (France distribution only)

- Prom Night (France distribution only)

- Rambo III (France distribution only; co-production with Carolco Pictures)

- Scanners (France distribution only)

- Sex, Lies, and Videotape (France distribution only)

1990's

- Asterix & Obelix Take On Caesar (UK and France distribution only; co-production with Canal+ and TF1)

- Austin Powers: International Man of Mystery (UK distribution only; produced by New Line Cinema)

- Austin Powers: The Spy Who Shagged Me (UK distribution only; produced by New Line Cinema)

- Basic Instinct (UK and France distribution only; co-production with Carolco Pictures)

- The Blair Witch Project (UK distribution only)

- Bound (UK distribution only)

- Cliffhanger (UK and France distribution only; co-production with Carolco Pictures)

- Cutthroat Island (UK and France distribution only; co-production with Carolco Pictures and Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer)

- Event Horizon (France distribution only; co-production with Paramount Pictures)

- The Fifth Element (UK distribution only; co-production with Gaumont)

- Freddy's Dead: The Final Nightmare (UK distribution only; co-production with New Line Cinema)

- Grey Owl (UK distribution only; co-production with 20th Century Fox, Largo Entertainment, BBC, Toho, and Allied Filmmakers)

- Highlander II: The Quickening (France distribution only)

- Jacob's Ladder (UK and France distribution only; co-production with Carolco Pictures)

- James and the Giant Peach (UK distribution only; co-production with Allied Filmmakers and Walt Disney Pictures)

- Jane Eyre (UK distribution only; co-production with Miramax Films)

- Jason Goes to Hell: The Final Friday (UK distribution only; co-production with New Line Cinema)

- Judge Dredd (UK distribution only; co-production with Hollywood Pictures)

- Kickboxer 2 (France distribution only)

- Lolita (co-production with Samuel Goldwyn Films)

- The Mask (UK and France distribution only; co-production with New Line Cinema)

- Mortal Kombat (UK and France distribution only; co-production with New Line Cinema)

- Pi (UK distribution only)

- The Player (UK distribution only; co-production with New Line Cinema)

- Ratcatcher (co-production with BBC Films)

- A River Runs Through It (UK distribution only)

- Rogue Trader (UK distribution only)

- Showgirls (UK and France distribution only; co-production with Carolco Pictures and United Artists)

- Sleepy Hollow (UK and France distribution only; co-production with Mandalay Entertainment)

- Stargate (UK and France distribution only; co-production with Carolco Pictures, Centropolis Entertainment, and Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer)

- Super Mario Bros. (France distribution only)

- Swingers (UK distribution only)

- Terminator 2: Judgment Day (UK and France distribution only; co-production with Carolco Pictures and Lightstorm Entertainment)

- Topsy-Turvy (UK distribution only; co-production with Thin Man Films)

- Total Recall (UK and France distribution only; co-production with Carolco Pictures)

- Universal Soldier (UK and France distribution only; co-production with Carolco Pictures and Centropolis Entertainment)

- The Virgin Suicides (UK and France distribution only)

- Wagons East (UK and France distribution only; co-production with Carolco Pictures)

- White Squall (UK distribution only; co-production with Hollywood Pictures and Scott Free Productions)

- The Wind in the Willows (UK and France distribution only; co-production with Walt Disney Pictures, 20th Century Fox, Columbia Pictures, and Allied Filmmakers)

- Wrongfully Accused (UK and France distribution only; co-production with Warner Bros., Constantin Film, and Morgan Creek Productions)

2000's

- Adulthood (UK distribution only; co-production with the UK Film Council)

- The Air I Breathe (UK distribution only; co-production with ThinkFilm)

- Alexander (France distribution only; co-production with Constantin Film, Pinewood Studios, Intermedia, France 3 Cinema and Warner Bros. Pictures)

- Alone in the Dark (France distribution only; co-production with Lionsgate Films, Brightlight Pictures, and Boll KG)

- Ask the Dust (UK distribution only; co-production with Paramount Vantage)

- Asterix & Obelix: Mission Cleopatra (UK and France distribution only; co-production with Canal+ and TF1)

- Asterix at the Olympic Games (UK and France distribution only; co-production with TF1 and Canal+)

- Austin Powers in Goldmember (UK distribution only; produced by New Line Cinema)

- Bad Education (France distribution only)

- Bandits (UK and France distribution only; co-production with Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Constantin Film and Hyde Park Entertainment)

- Basic Instinct 2 (UK and France distribution only; co-production with Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Sony Pictures Releasing, Intermedia Films, and C2 Pictures)

- Be Kind Rewind (UK distribution only; co-production with Focus Features and New Line Cinema)

- The Believer (UK distribution only; co-production with Fireworks Entertainment)

- Big Nothing (co-production with Ingenious Media)

- Black Book (France distribution only; co-production with Clockwork Pictures and Babelsberg Studio)

- Black Christmas (UK distribution only; co-production with Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer and the Weinstein Company)

- Blindness (UK and France distribution only)

- Bride and Prejudice (UK distribution only; co-production with Miramax Films)

- Broken Embraces (UK distribution only; co-production with Sony Pictures Classics and Universal Pictures)

- Bulletproof Monk (UK distribution only; co-production with Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer)

- Chéri (co-production with Bill Kenwright Films and UK Film Council)

- Chicken Run (co-production with DreamWorks Animation and Aardman Animations)

- The Chorus (UK and France distribution only)

- Company Man (UK and France distribution only; co-production with Intermedia Films)

- The Cottage (co-production with the UK Film Council)

- Crash (UK distribution only; co-production with Lionsgate)

- The Descent (UK and France distribution only; co-production with Celador Films)

- The Descent Part 2 (UK and France distribution only; co-production with Celador Films)

- The Diving Bell and the Butterfly (France distribution only; co-production with France 3 Cinema)

- DOA: Dead or Alive (France distribution only; co-production with Constantin Film, Team Ninja, and Dimension Films)

- Doomsday (France distribution only; co-production with UK Film Council, Rogue Pictures, Relativity Media, and Universal Pictures)

- The Duchess (co-production with Paramount Vantage)

- Eastern Promises (UK distribution only; co-production with BBC Films)

- Eden Lake (co-production with The Weinstein Company)

- Enemy at the Gates (co-production with Mandalay Pictures and Paramount Pictures)

- Evelyn (UK and France distribution only)

- Fantastic Four (2005) (France distribution only; co-production with 20th Century Fox, 1492 Pictures, Marvel Entertainment, and Constantin Film)

- Fantastic Four: Rise of the Silver Surfer (France distribution only; co-production with 20th Century Fox, 1492 Pictures, Marvel Entertainment, and Constantin Film)

- Far Cry (France distribution only; co-production with Vivendi Entertainment, Touchstone Pictures, 20th Century Fox, Ubisoft, Brightlight Pictures, and Boll KG)

- Farce of the Penguins (co-production with Permut Presentations and ThinkFilm)

- The Fox and the Child (UK distribution only; produced by Canal+ and France 3 Cinema)

- Gerry (UK distribution only)

- The Goods: Live Hard, Sell Hard (UK distribution only; co-production with Paramount Vantage)

- Hannibal (France distribution only; co-production with Universal Pictures, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Scott Free Productions, and Dino De Laurentiis Company)

- Hannibal Rising (France distribution only; co-production with Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer and Dino De Laurentiis Company)

- Hardball (UK and France distribution only; co-production with Fireworks Entertainment and Paramount Pictures)

- Hard Rain (UK and France distribution only; co-production with Paramount Pictures, Lawrence Gordon Productions, Mutual Film Company, BBC, and Toho)

- Honest (UK distribution only)

- The Hottie and the Nottie (co-production with Summit Entertainment)

- House of the Dead (France distribution only; co-production with Lionsgate Films and Boll KG)

- Interstate 60 (UK distribution only; co-production with Fireworks Entertainment)

- Jeepers Creepers (UK distribution only; co-production with United Artists and American Zoetrope)

- Jeepers Creepers 2 (UK distribution only; co-production with United Artists and American Zoetrope)

- Jeepers Creepers 3 (UK distribution only; co-production with Screen Media Films and American Zoetrope)

- K-19: The Widowmaker (France distribution only; co-production with Paramount Pictures, Intermedia, BBC, Toho, and National Geographic Films)

- Lara Croft: Tomb Raider (France distribution only; co-production with Paramount Pictures, Lawrence Gordon Productions, Mutual Film Company, BBC, Toho, and Eidos)

- Lara Croft Tomb Raider: The Cradle of Life (France distribution only; co-production with Paramount Pictures, Lawrence Gordon Productions, Mutual Film Company, BBC, Toho, and Eidos)

- Lost in Translation (France distribution only; co-production with Focus Features)

- Love Labour's Lost (UK and France distribution only; co-production with Miramax, Shepperton Studios and Intermedia)

- The Magic Roundabout (UK and France distribution only; co-production with France 3 Cinema, and UK Film Council)

- Marie Antoinette (France distribution only; co-production with American Zoetrope and Columbia Pictures)

- Memento (UK distribution only; co-production with Summit Entertainment and Newmarket Films)

- Mr. & Mrs. Smith (France distribution only; co-production with Summit Entertainment, Regency Enterprises, and 20th Century Fox)

- Mr. Nobody (France distribution only; co-production with Wild Bunch Productions and Canal+)

- Mulholland Drive (UK distribution only; co-production with StudioCanal)

- Pandorum (France distribution only; co-production with Constantin Film and Overture Films)

- The Patriot (France distribution only; co-production with Columbia Pictures, Centropolis Entertainment, Lawrence Gordon Productions, Mutual Film Company, BBC, and Toho)

- Perfume: The Story of a Murderer (UK distribution only; co-production with Constantin Film)

- The Pianist (UK distribution only)

- Rat Race (UK distribution only; co-production with Fireworks Entertainment and Paramount Pictures)

- Red Dragon (France distribution only; co-production with Universal Pictures, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, and Dino De Laurentiis Company)

- Rescue Dawn (UK distribution only; co-production with Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer)

- Resident Evil (UK distribution only; co-production with Constantin Film)

- Resident Evil: Apocalypse (UK distribution only; co-production with Constantin Film)

- Resident Evil: Extinction (UK distribution only; co-production with Constantin Film)

- Saw (France distribution only; co-production with Twisted Pictures and Lionsgate Films)

- Saw II (France distribution only; co-production with Twisted Pictures and Lionsgate Films)

- Saw III (France distribution only; co-production with Twisted Pictures and Lionsgate Films)

- The Score (UK and France distribution only; co-production with Mandalay Entertainment)

- The Scouting Book for Boys (co-production with Film4 Productions and Celador Films)

- Silent Hill (UK distribution only; co-production with Davis Films, Konami, and Team Silent)

- Slumdog Millionaire (UK and France distribution only; co-production with Celador Films, Film4 Productions, Warner Bros. Pictures and Fox Searchlight Pictures)

- Son of the Mask (UK and France distribution only; co-production with New Line Cinema)

- Terminator 3: Rise of the Machines (UK and France distribution only; co-production with Sony Pictures Releasing, Intermedia Films, and C2 Pictures)

- Thunderpants (UK distribution only; co-production with CP Medien AG and Mission Pictures)

- Touching the Void (UK distribution only; co-production with IFC Films, Film4 Productions and the UK Film Council)

- Transamerica (UK distribution only; co-production with IFC Films and The Weinstein Company)

- Two Brothers (UK and France distribution only; co-production with Universal Pictures and France 3 Cinema

- The Walker (UK and France distribution only)

- What Just Happened (UK distribution only, produced by Magnolia Pictures)

- White Noise (UK distribution only; co-production with Universal Pictures, Brightlight Pictures, and Gold Circle Films)

- Wrong Turn (UK distribution only; co-production with Regency Enterprises, Constantin Film, and Summit Entertainment)

- Youth Without Youth (UK distribution only; co-production with American Zoetrope and Sony Pictures Classics)

- Zoolander (UK and France distribution only; co-production with Paramount Pictures, VH1 Films, Red Hour Films, and Village Roadshow Pictures)

2010s

French

- 127 Hours (UK and France distribution; co-production with Fox Searchlight Pictures, Dune Entertainment, Warner Bros. Pictures, Everest Entertainment, Film4 Productions, Darlow Smithson Productions, and Cloud 8 Films)

- Beauty and the Beast (France distribution only; co-production with TF1, Canal+, Ciné+ and Studio Babelsberg)

- Centurion (UK and France distribution only; co-production with Celador Films)

- Enemy (studio credit only; co-production with Entertainment One, Corus Entertainment, Telefilm Canada and Roxbury Pictures)

- Fantastic Four (2015) (France distribution only; co-production with 20th Century Fox, Genre Films, Marvel Entertainment, and Constantin Film)

- Florence Foster Jenkins (UK and France distribution only; co-production)

- The Illusionist (UK and France distribution only; co-production with Canal+, France 3 Cinema, Django Films, Warner Bros. Pictures and Sony Pictures Classics)

- Jacky in Women's Kingdom (co-production with France 2 Cinema, France Télévisions, Canal+, Ciné+ and Orange Studio)

- Jappeloup (co-production with Canal+, Ciné+, Orange Studio and TF1)

- Judy (co-production with BBC Films and Calamity Films)

- Julieta (UK and France distribution only)

- Mandela: Long Walk to Freedom (UK and France distribution only; co-production with Origin Pictures)

- No One Lives (co-production with WWE Studios and Anchor Bay Films)

- Oceans (France distribution only; co-production with Canal+, France 2 Cinema, France 3 Cinema and Participant Media, US and Canadian distribution is Disneynature)

- Pain and Glory (France distribution only)

- Philomena (UK and France distribution only; co-production with BBC Films, Canal+, and Ciné+)

- Pride (UK and France distribution only; co-production with CBS Films, BBC Films, British Film Institute, Canal+ and Ciné+)

- Playmobil: The Movie (France distribution only; co-production with Method Animation, ON Animation Studios, and DMG Entertainment)

- Resident Evil: Afterlife (UK distribution only; co-production with Constantin Film)

- Resident Evil: The Final Chapter (UK distribution only; co-production with Constantin Film)

- Resident Evil: Retribution (UK distribution only; co-production with Constantin Film)

- Rush (France distribution only; produced by Imagine Entertainment, Revolution Media, Working Title Films, StudioCanal, Exclusive Media, Cross Creek Pictures and Universal Pictures)

- Savages (France distribution only; co-production with Relativity Media and Universal Pictures)

- Selma (co-production with Harpo Films, Paramount Pictures and Celador Films)

- Silent Hill: Revelation (UK and France distribution; co-production with Davis Films, Konami, and Team Silent)

- Suffragette (UK and France distribution only; co-production with Film4 Productions, Canal+ and Ciné+)

- Titeuf (France distribution only; co-production with MoonScoop Group)

- Trance (International sales only; co-production with Fox Searchlight Pictures, Film4 Productions and Indian Paintbrush)

- Twixt (co-production with American Zoetrope)

- A United Kingdom (co-production with BBC Films, Ingenious Media and British Film Institute)

- Viceroy's House (UK and France distribution only)

- Why I Did (Not) Eat My Father (France distribution)

- Zarafa (France distribution only; co-production with France 3 Cinema)

2020's

French

- Benedetta

- CODA

- Mon Cousin

- Le Meilleur Reste à Cenir

- Petit Pays

British

See also

- Category:Pathé films

- Pathé Records

- Pathé News and British Pathé

- List of film serials by studio lists the Pathé film serials

- Fumagalli, Pion & C., Italian Pathé importer

References

Notes

- http://2017.pathe.com/en/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Pathe-year_book-2017.pdf

- "History of British Pathé". www.britishpathe.com. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- "Trade catalogs from Pathé Frères SA". National Museum of American History. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- Hoffmann, Frank; Howard Ferstler (2005). The Encyclopedia of Recorded Sound. CRC Press. ISBN 0-415-93835-X.

- Copeland, George; Ronald Dethlefson (1999). Pathé Records and Phonographs in America, 1914-1922 (1 ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Mulholland Press. OCLC 44146208.

- "Pathé vertical-cut disc record (1905 – 1932) – Museum Of Obsolete Media". www.obsoletemedia.org. Retrieved 12 February 2018.

- Fabrizio, Timothy; George Paul (2000). Discovering Antique Phonographs. Atglen PA: Sciffer Publishing Ltd. ISBN 0-7643-1048-8.

- "Who's Who of Victorian Cinema". www.victorian-cinema.net.

- Abel 1999, pp. 23–24.

- Abel 1999, p. 25.

- Abel 1999, p. 25.

- "Film and Electrolux through the ages". Electrolux. Archived from the original on 1 February 2014. Retrieved 13 January 2013.

- Abel 1999, p. 26.

- Researcher's Guide to British Newsreels 1993, p. 80.

- Abel 1999, pp. 32–35.

- Abel 1999, pp. 32–35.

- Willems, Gilles "Les origines de Pathé-Natan" In Une Histoire Économique du Cinéma Français (1895–1995), Regards Croisés Franco-Américains, Pierre-Jean Benghozi and Christian Delage, eds. Paris: Harmattan, Collection Champs Visuels, 1997. English translation: "The origins of Pathé-Natan." Archived 9 January 2008 at the Wayback Machine La Trobe University. Retrieved: 1 January 2017.

- Abel, Richard. French Cinema: The First Wave 1915–1929 Paperback ed. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1987, ISBN 0-691-00813-2.

- Willems, Gilles. "Les Origines du Groupe Pathé-Natan et le Modele Americain." Vingtième Siècle 46, April–June 1995.

- Hutchinson, Pamela (14 December 2015). "In need of rehabilitation: Bernard Natan, the Holocaust victim who saved France's film industry". The Guardian. Retrieved 22 November 2017.

- Gant 1999, p. 370.

- "Pathé, Gaumont and Seydoux: Pathe." Archived 24 September 2010 at the Wayback Machine Ketupa.net. Retrieved: 19 October 2010.

- Williams, Michael (8 June 1999). "Vivendi nabs sat stakes for Pathe merger". Variety. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- https://www.pathe.com/sites/default/files/PATHE_2016_UK_PLANCHES_OK.pdf

- Groupe, Olympique Lyonnais. "Shareholders - Olympique Lyonnais Groupe". investisseur.olympiquelyonnais.com.

- London, Tim Adler in (1 February 2011). "Pathé UK Swaps Warner Bros For Fox".

Bibliography

- Abel, Richard. The Red Rooster Scare: Making Cinema American, 1900–1910. Berkeley, California: University of California Press, 1999. ISBN 0-520-21478-1.

- Gant, Tina. International Directory of Company Histories, Volume 8; Volume 29. Farmington Hills, Michigan: Gale, 1999. ISBN 1-5-586-2392-2.

- Researcher's Guide to British Newsreels. London: British Universities Film & Video Council. 1993. ISBN 0-901299-65-0.