Shastasaurus

Shastasaurus ("Mt. Shasta lizard") is an extinct genus of ichthyosaur from the middle and late Triassic, and is the largest known marine reptile.[2] Specimens have been found in the United States, Canada, and China.[3]

| Shastasaurus | |

|---|---|

| |

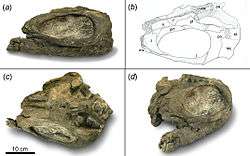

| Partial skull of Shastasaurus pacificus (UCMP 9017) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | †Ichthyosauria |

| Suborder: | †Longipinnati |

| Node: | †Merriamosauria |

| Family: | †Shastasauridae Merriam, 1895 |

| Genus: | †Shastasaurus Merriam, 1895 |

| Type species | |

| †Shastasaurus pacificus Merriam, 1895 | |

| Species | |

|

†S. pacificus | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Description

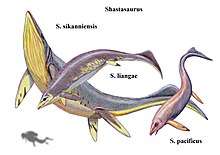

Shastasaurus lived during the late Triassic period. The type species Shastasaurus pacificus is known from California. A second possible species of Shastasaurus, S. sikanniensis, is known from the Pardonet Formation British Columbia, dating to the middle Norian age (about 210 million years ago).[4] If S. sikanniensis belongs to Shastasaurus, it would be the largest species, measuring up to 21 metres (69 ft).

Shastasaurus was highly specialized, and differed considerably from other ichthyosaurs. It was very slender in profile. The largest specimens had a ribcage slightly less than 2 metres (6.6 ft) deep despite a distance of over 7 metres (23 ft) between its flippers.[4] Due to its unusually short, toothless snout (compared to the long, toothed, dolphin-like snouts of most ichthyosaurs) it was proposed that Shastasaurus was thought to be a suction feeder, feeding primarily on soft-bodied cephalopods,[5] although current research indicates ichthyosaur jaws do not fit the suction-feeding profile.[6]

In S. liangae, the only species with several well preserved skulls, the skull measures only 8.3% of the total body length (9.3% in a juvenile specimen). Unlike the related Shonisaurus, even juvenile Shastasaurus completely lacked teeth. The snout was highly compressed via a unique arrangement of skull bones. Unlike almost all other reptiles, the nasal bone, which usually forms the mid part of the skull, extended to the very tip of the snout, and all bones of the snout tapered to abrupt points.[5]

Shastasaurus was also traditionally depicted with a dorsal fin, a feature found in more advanced ichthyosaurs. However, other shastasaurids likely lacked dorsal fins, and there is no evidence to support the presence of such a fin in any species. The upper fluke of the tail was probably also much less developed than the shark-like tails found in later species.[7]

Species and synonyms

The type species of Shastasaurus is S. pacificus, from the late Carnian of northern California. It is known only from fragmentary remains, which have led to the assumption that it was a 'normal' ichthyosaur in terms of proportions, especially skull proportions. Several species of long-snouted ichthyosaur were referred to Shastasaurus based on this misinterpretation, but are now placed in other genera (including Callawayia and Guizhouichthyosaurus).[5]

Shastasaurus may include a second species, Shastasaurus liangae. It is known from several good specimens, and was originally placed in the separate genus Guanlingsaurus. Complete skulls show that it had an unusual short and toothless snout. S. pacificus probably also had a short snout, although its skull is incompletely known. The largest specimen of S. liangae (YIGMR SPCV03109) measures 8.3 metres (27 ft) long. A juvenile specimen (YIGMR SPCV03108) has also been found, measuring 3.74 metres (12.3 ft) in length.[5]

S. sikanniensis was originally described in 2004 as a large species of Shonisaurus. However, this classification was not based on any phylogenetic analysis, and the authors also noted similarities with Shastasaurus. The first study testing its relationships, in 2011, supported the hypothesis that it was indeed more closely related to Shastasaurus than to Shonisaurus, and it was reclassified as Shastasaurus sikanniensis.[5] However, a 2013 analysis supported the original classification, finding it more closely related to Shonisaurus than to Shastasaurus.[8] Specimens belonging to S. sikanniensis have been found in the Pardonet Formation British Columbia, dating to the middle Norian age (about 210 million years ago).[4]

In 2009, Shang & Li reclassified the species Guizhouichthyosaurus tangae as Shastasaurus tangae. However, later analysis showed that Guizhouichthyosaurus was in fact closer to more advanced ichthyosaurs, and so cannot be considered a species of Shastasaurus.[5]

Dubious species that were referred to this genus include S. carinthiacus (Huene, 1925) from the Austrian Alps and S. neubigi (Sander, 1997) from the German Muschelkalk.[3] S. neubigi, however, has recently been re-described and reassigned to its own genus, Phantomosaurus.[9]

Synonyms of S. / G. liangae:

Guanlingichthyosaurus[10] liangae Wang et al., 2008 (lapsus calami)

Synonyms of S. pacificus:

Shastasaurus alexandrae Merriam, 1902

Shastasaurus osmonti Merriam, 1902

See also

- List of ichthyosaurs

- Timeline of ichthyosaur research

References

- "†Shastasaurus Merriam 1895 (ichthyosaur)". Paleobiology Database. Fossilworks. Retrieved 11 August 2017.

- Hilton, Richard P., Dinosaurs and Other Mesozoic Animals of California, University of California Press, Berkeley 2003 ISBN 0-520-23315-8, at pages 90-91.

- Shang Qing-Hua, Li Chun (2009). "On the occurrence of the ichthyosaur Shastasaurus in the Guanling Biota (Late Triassic), Guizhou, China" (PDF). Vertebrata PalAsiatica. 47 (3): 178–193.

- Nicholls, E.L.; Manabe, M. (2004). "Giant ichthyosaurs of the Triassic - a new species of Shonisaurus from the Pardonet Formation (Norian: Late Triassic) of British Columbia". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 24 (3): 838–849. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2004)024[0838:GIOTTN]2.0.CO;2.

- Sander P, Chen X, Cheng L, Wang X (2011). Claessens L (ed.). "Short-Snouted Toothless Ichthyosaur from China Suggests Late Triassic Diversification of Suction Feeding Ichthyosaurs". PLoS ONE. 6 (5): e19480. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0019480. PMC 3100301. PMID 21625429.

- Motani R, Tomita T, Maxwell E, Jiang D, Sander P (2013). "Absence of Suction Feeding Ichthyosaurs and Its Implications for Triassic Mesopelagic Paleoecology". PLoS ONE. 8 (12): e66075. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0066075. PMC 3859474. PMID 24348983.

- Wallace, D.R. (2008). Neptune's Ark: From Ichthyosaurs to Orcas. University of California Press, 282pp.

- Ji, C.; Jiang, D. Y.; Motani, R.; Hao, W. C.; Sun, Z. Y.; Cai, T. (2013). "A new juvenile specimen of Guanlingsaurus (Ichthyosauria, Shastasauridae) from the Upper Triassic of southwestern China". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 33 (2): 340–348. doi:10.1080/02724634.2013.723082.

- Maisch, M. W.; Matzke, A. T. (2006). "The braincase ofPhantomosaurus neubigi(Sander, 1997), an unusual ichthyosaur from the Middle Triassic of Germany". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 26 (3): 598–607. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2006)26[598:TBOPNS]2.0.CO;2.

- Xiaofeng, W.; Bachmann, G. H.; Hagdorn, H.; Sander, P. M.; Cuny, G.; Xiaohong, C.; Chuanshang, W.; Lide, C.; Long, C.; Fansong, M.; Guanghong, X. U. (2008). "The Late Triassic Black Shales of the Guanling Area, Guizhou Province, South-West China: A Unique Marine Reptile and Pelagic Crinoid Fossil Lagerstätte". Palaeontology. 51: 27–61. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2007.00735.x.