Catalan Countries

Catalan Countries (Catalan: Països Catalans, Eastern Catalan: [pəˈizus kətəˈlans]) refers to those territories where the Catalan language, or a variant of it, is spoken.[1][2] They include the Spanish regions of Catalonia, Valencia, the Balearic Islands and parts of Aragon and Murcia,[3] as well as the department of Pyrénées-Orientales (including Cerdagne, Vallespir and Roussillon) in France, the Principality of Andorra, and the city of Alghero in Sardinia (Italy).[1][4][5][6] In the context of Catalan nationalism, the term is sometimes used in a more restricted way to refer to just Catalonia, Valencia and the Balearic Islands.[7][8][9] The Catalan Countries do not correspond to any present or past political or administrative unit, though most of the area belonged to the Crown of Aragon in the Middle Ages. Parts of Valencia (Spanish) and Catalonia (Occitan) are not Catalan-speaking.

| Catalan Countries Països Catalans | |

|---|---|

The concept of the Catalan Countries includes territories of the following regions: | |

| State | Territory |

| Where Catalan is the sole official language | |

The "Catalan Countries" have been at the centre of both cultural and political projects since the late 19th century. Its mainly cultural dimension became increasingly politically charged by the late 1960s and early 1970s, as Francoism began to die out in Spain, and what had been a cultural term restricted to connoisseurs of Catalan philology became a divisive issue during the Spanish Transition period, most acrimoniously in Valencia during the 1980s. Modern linguistic and cultural projects include the Institut Ramon Llull and the Fundació Ramon Llull, which are run by the governments of the Balearic Islands, Catalonia and Andorra, the Department Council of the Pyrénées-Orientales, the city council of Alghero and the Network of Valencian Cities. Politically, it involves a pan-nationalist project to unite the Catalan-speaking territories of Spain and France, often in the context of the independence movement in Catalonia. The political project does not currently enjoy wide support, particularly outside Catalonia, where some sectors view it as an expression of pancatalanism.[10][11][12][13] Linguistic unity, however, is widely recognized[14][15][16][17][18][19][20] except for the followers of a political movement known as Blaverism,[21] even though some of its main organizations have recently abandoned such idea.[22]

Different meanings

Països Catalans has different meanings depending on the context. These can be roughly classified in two groups: linguistic or political, the political definition of the concept being the widest, since it also encompasses the linguistic side of it.

As a linguistic term, Països Catalans is used in a similar fashion to the English Anglosphere, the French Francophonie, the Portuguese Lusofonia or the Spanish Hispanophone territories. However, it is not universally accepted, even as a linguistic concept, in the territories it purports to unite.

As a political term, it refers to a number of political projects[23] as advocated by supporters of Catalan independence. These, based on the linguistic fact, argue for the existence of a common national identity that would surpass the limits of each territory covered by this concept and would apply also to the remaining ones. These movements advocate for "political collaboration"[24] amongst these territories. This often stands for their union and political independence.[25] As a consequence of the opposition these political projects have received –notably in some of the territories described by this concept[26] – some cultural institutions avoid the usage of Països Catalans in some contexts, as a means to prevent any political interpretation; in these cases, equivalent expressions (such as Catalan-speaking countries) or others (such as the linguistic domain of Catalan language) are used instead.[27]

Component territories

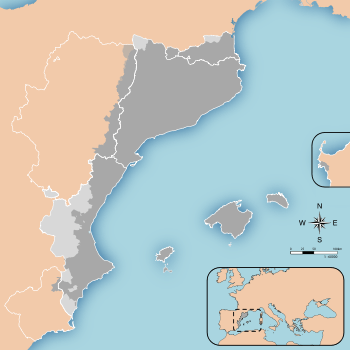

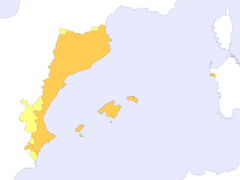

| The Catalan / Valencian cultural domain |

|---|

Map of Catalan language domain |

|

Language

|

|

People

|

|

Geo-political divisions

|

|

Government and politics

|

Catalan and its variants are spoken in:

- the Spanish Autonomous Communities of

- Catalonia – even though in the comarca of Val d'Aran, Occitan is considered the language proper to that territory;

- Aragon, in a Catalan-speaking area known as "La Franja de Ponent" ("Western Strip");

- the Balearic Islands and

- as Valencian, in the Valencian Community, with the exception of some western and southern territories where Spanish is the only language spoken;

- Andorra, a European sovereign state where Catalan is the national and only official language.

- most of the French department of the Pyrénées-Orientales, also called Le Pays Catalan (The Catalan Country) in French or Catalunya (del) Nord (Northern Catalonia) in Catalan;

- the Italian city of Alghero, in the island of Sardinia, where a variant of Catalan is spoken.

Catalan is the official language of Andorra, co-official with Spanish and Occitan in Catalonia, co-official with Spanish in the Balearic Islands and the Valencian Community—with the denomination of Valencian in the latter—and co-official with Italian in the city of Alghero. It is also part of the recognized minority languages of Italy along with Sardinian, also spoken in Alghero.

It is not official in Aragon, Murcia or the Pyrénées-Orientales, even though on 10 December 2007 the General Council of the Pyrénées-Orientales officially recognized Catalan, along with French, as a language of the department.[28] In 2009, the Catalan language was declared llengua pròpia (with the Aragonese language) of Aragon.[29]

Cultural dimension

There are several endeavors and collaborations amongst some of the diverse government and cultural institutions involved. One such case is the Ramon Llull Institute (IRL), founded in 2002 by the government of the Balearic Islands and the government of Catalonia. Its main objective is to promote the Catalan language and culture abroad in all its variants, as well as the works of writers, artists, scientists and researchers of the regions which are part of it. The Xarxa Vives d'Universitats (Vives Network of Universities), an association of universities of Catalonia, Valencia, the Balearic Islands, Northern Catalonia and Andorra founded in 1994, was incorporated into the IRL in 2008.[30] Also in 2008, in order to extend the collaboration to institutions from all across the "Catalan Countries", the IRL and the government of Andorra (which formerly had enjoyed occasional collaboration, most notably in the Frankfurt Book Fair of 2007) created the Ramon Llull Foundation (FRL), an international cultural institution with the same goals as the IRL.[31][32] In 2009, the General Council of the Pyrénées-Orientales, the city council of Alghero and the Network of Valencian Cities (an association of a few Valencian city councils) joined the FRL as well.[33][34][35] In December 2012 the government of the Balearic islands, now dominated by the conservative and pro-Spain Partido Popular (PP), announced that the representatives of the Balearic islands were withdrawing from the Llull institute.[36]

A number of cultural organizations, specifically Òmnium Cultural in Catalonia, Acció Cultural del País Valencià in Valencia, and Obra Cultural Balear in the Balearic islands (collectively the "Llull Federation"), advocate independence as well as the promotion of Catalan language and culture.[37][38]

Political dimension

The political projects that centre on the Catalan Countries have been described as a "hypothetical and future union" of the various territories.[39] In many cases it involves the Spanish autonomous communities of Catalonia, Valencia and the Balearics.[7][8] The 2016 electoral programme of Valencian parties Compromís and Podemos spoke of a "federation" between the Valencian Community, the Balearic Islands and Catalonia. They are to campaign for an amendment to article 145 of the Spanish constitution, which forbids federation of autonomous communities.[9] The territories concerned may also include Roussillon and La Franja.[39][40][41]

Many in Spain see the concept of the Països Catalans as regional exceptionalism, counterpoised to a centralizing Spanish and French national identity. Others see it as an attempt by a Catalonia-proper-centered nationalism to lay a hegemonic claim to Valencia, the Balearic Islands or Roussillon, where the prevailing feeling is that they have their own respective historical personalities, not necessarily related to Catalonia's. The Catalan author and journalist Valentí Puig described the term as "inconvenient", saying it has generated more reactions against it than adhesions.[42]

The concept has connotations that have been perceived as problematic and controversial when establishing relations between Catalonia and other areas of the Catalan linguistic domain.[43][44][45] It has been characterised as a "phantom reality" and an "unreal and fanciful space".[46][47] The pro-Catalan independence author Germà Bel called it an "inappropriate and unfortunate expression lacking any historic, political or social basis",[48] while Xosé Manoel Núñez Seixas spoke of the difficulties in uniting a historicist concept linked to common membership of the Crown of Aragon with a fundamentally linguistic construct.[49]

In many parts of the territories designated by some as Països Catalans, Catalan nationalist sentiment is uncommon. For example, in the Valencian Community case, the Esquerra Repúblicana del País Valencià (ERPV) is the most relevant party explicitly supportive of the idea but its representation is limited to a total of four local councilors elected in three municipalities[50] (out of a total of 5,622 local councilors elected in the 542 Valencian municipalities). At the regional level, it has run twice (2003 and 2007) to the regional Parliament election, receiving less than 0.50% of the total votes.[51] In all, its role in Valencian politics is currently marginal.[52]

There are other parties which sporadically use this term in its cultural or linguistical sense, not prioritizing a national-political unity, as in the case of the Bloc Nacionalista Valencià. The Valencian Nationalist Bloc (Valencian: Bloc Nacionalista Valencià, Bloc or BNV; IPA: [ˈblɔɡ nasionaˈlista valensiˈa]) is the largest Valencian nationalist party in the Valencian Country, Spain. The Bloc's main aim is, as stated in their guidelines, "to achieve full national sovereignty for the Valencian people, and make it legally declared by a Valencian sovereign Constitution allowing the possibility of association with the countries which share the same language, history and culture".[53] Since 2011, they are part of the Coalició Compromís coalition, which won six seats in the 2011 Valencian regional elections and 19 in the 2015 elections, becoming the third largest party in the regional parliament.

Some of the most vocal defenders or promoters of the "Catalan Countries" concept (such as Joan Fuster, Josep Guia or Vicent Partal) were Valencian.

The subject became very controversial during the politically agitated Spanish Transition in what was to become the Valencian Community, especially in and around the city of Valencia. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, as the Spanish Autonomous Communities system took shape, the controversy reached its height. Various Valencian right-wing politicians (originally from Unión de Centro Democrático) fearing what was seen as an annexation attempt from Catalonia, fueled a violent Anti-Catalanist campaign against local supporters of the concept of the Països Catalans, which even included a handful of unsuccessful attacks with explosives against authors perceived as flagships of the concept, such as Joan Fuster or Manuel Sanchis i Guarner. The concept's revival during this period was behind the formation of the fiercely opposed and staunch anti-Catalan blaverist movement, led by Unió Valenciana, which, in turn, significantly diminished during the 1990s and the 2000s as the Països Catalans controversy slowly disappeared from the Valencian political arena.

This confrontation between politicians from Catalonia and Valencia very much diminished in severity during the course of the late 1980s and, especially, the 1990s as the Valencian Community's regional government became consolidated. Since then, the topic has lost most of its controversial potential, even though occasional clashes may appear from time to time, such as controversies regarding the broadcasting of Catalan television in Valencia—and vice versa—or the usage by Catalan official institutions of terms which are perceived in Valencia as Catalan nationalistic, such as Països Catalans or País Valencià (Valencian Country).

A 2004 poll in Valencia found that a majority of the population in this region considered Valencian to be a different language to Catalan.[54] This position is especially supported by people who do not use Valencian regularly.[55] Furthermore, the data indicate that younger people educated in Valencian are much less likely to hold these views. According to an official poll in 2014,[56] 52% of Valencians considered Valencian to be a language different from Catalan, while 41% considered the languages to be the same. This poll showed significant differences regarding age and level of education, with a majority of those aged 18–24 (51%) and those with a higher education (58%) considering Valencian to be the same language as Catalan. This can be compared to those aged 65 and above (29%) and those with only primary education (32%), where the same view has its lowest support.

In 2015, the Spanish newspaper ABC reported that the Catalan government of Artur Mas had spent millions of euros to promote Catalanism in Valencia over the previous three years.[57]

As for the other territories, there are no political parties even mentioning the Països Catalans as a public issue neither in Andorra, nor in la Franja, Carche or Alghero. In the Balearic islands, support for parties related to Catalan nationalism is around 10% of the total votes.[58] Reversely, the Popular Party –which is a staunch opponent of whatever political implications for the Països Catalans concept– is the majority party in Valencia and the Balearic islands.

Even though the topic has been largely absent from the political agenda as of late, in December 2013 the regional Parliament of the Balearic islands passed an official declaration[59] in defence of its autonomy and in response to a prior declaration by the Catalan regional Parliament which included reference to the term in question. In the declaration of the Balearic islands parliament, it was stated that the so-called "Països Catalans do not exist and the Balearic islands do not take part in any 'Catalan country' whatsoever".[60]

In August 2018, the ex-mayor of Alghero, Carlo Sechi, defined algherese identity as part of the Catalan culture whilst politically defining Alghero as part of the Sardinian nation.[61]

The Spanish Constitution of 1978 contains a clause forbidding the formation of federations amongst autonomous communities. Therefore, if it were the case that the Països Catalans idea gained a majority democratic support in future elections, a constitutional amendment would still be needed for those parts of the Països Catalans lying in Spain to create a common legal representative body, even though in the addenda to the Constitution there is a clause allowing an exception to this rule in the case of Navarre, which can join the Basque Country should the people choose to do so.[62]

Catalans in the French territory of Northern Catalonia, although proud of their language and culture, are not committed to independence.[63] Jordi Vera, a CDC councillor in Perpignan, has said that his party favoured closer trade and transport relationships with Catalonia, and that he believed Catalan independence would improve the prospects of that happening, but that secession from France was "not on the agenda".[63][64] When Catalans took to the streets in 2016 under the banner of "Oui au Pays catalan" ("Yes to the Catalan Country") to protest the French government's decision to combine Languedoc-Roussillon, the region which contained Northern Catalonia, with Midi-Pyrénées to create a new region to be called Occitanie, the French magazine Le Point said that the movement was "completely unrelated to the situation on the other side of the border", and that it was "more directed against Toulouse [the chief city of Occitanie] than against Paris or for Barcelona."[65] Oui au Pays catalan, which stood in the 2017 French legislative election, said that's its aim is a "territorial collectivity" within the French Republic on the same lines as Corsica.[66] Every year, though, there are between 300 and 600 people in a demonstration to commemorate the 1759 Treaty of the Pyrenees, that separated Northern Catalonia from the South.[67]

Etymology

The term Països Catalans was first documented in 1876 in Historia del Derecho en Cataluña, Mallorca y Valencia. Código de las Costumbres de Tortosa, I (History of the Law in Catalonia, Majorca and Valencia. Code of the Customs of Tortosa, I) written by the Valencian Law historian Benvingut Oliver i Esteller.

The term was both challenged and reinforced by the use of the term "Occitan Countries" from the Oficina de Relacions Meridionals (Office of Southern Relations) in Barcelona by 1933. Another proposal which enjoyed some popularity during the Renaixença was "Pàtria llemosina" (Limousine Fatherland), proposed by Víctor Balaguer as a federation of Catalan-speaking provinces; both these coinages were based on the theory that Catalan is a dialect of Occitan.

None of these names reached widespread cultural usage and the term nearly vanished until it was rediscovered, redefined and put in the center of the identity cultural debate by Valencian writer Joan Fuster. In his book Nosaltres, els valencians (We, the Valencians, published in 1962) a new political interpretation of the concept was introduced; from the original, meaning roughly Catalan-speaking territories, Fuster developed a political inference closely associated to Catalan nationalism. This new approach would refer to the Catalan Countries as a more or less unitary nation with a shared culture which had been divided by the course of history, but which should logically be politically reunited. Fuster's preference for Països Catalans gained popularity, and previous unsuccessful proposals such as Comunitat Catalànica (Catalanic Community) or Bacàvia[68] (after Balearics-Catalonia-Valencia) diminished in use.

Today, the term is politically charged, and tends to be closely associated with Catalan nationalism and supporters of Catalan independence. The idea of uniting these territories in an independent state is supported by a number of political parties, ERC being the most important in terms of representation (32 members in the Parliament of Catalonia) and CUP (10 members). ERPV, PSAN (currently integrated in SI), Estat Català also support this idea to a greater or lesser extent.

See also

- Catalans

- Catalan Language

- Blaverism

- Catalan independence

- Gate of the Catalan Countries

- Pi de les Tres Branques

- Pan-nationalism

References

- Stone, Peter (2007). Frommer's Barcelona (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. p. 77. ISBN 0470096926.

- "Volume 6". Enciclopedia universal Larousse (in Spanish) (Edición especial para RBA Coleccionables, S.A. ed.). Éditions Larousse. 2006. p. 1133. ISBN 84-8332-879-8.

Catalan Countries: denomination that encompasses the Catalan-speaking territories

- Wheeler, Max (2005). The Phonology of Catalan. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-19-925814-7.

- Guibernau, Montserrat (2010). "Catalonia: nationalism and intellectuals in nations without states". In Guibernau, Montserrat; Rex, John (eds.). The Ethnicity Reader: Nationalism, Multiculturalism and Migration. Polity. p. 151. ISBN 0745647014.

- "Catalonia profile". BBC News. 21 April 2016.

- Conversi, Daniele (2000). The Basques, the Catalans and Spain: Alternative Routes to Nationalist Mobilisation. University of Nevada Press. p. xv. ISBN 0874173620.

- Núñez Seixas, Xosé M. (2013). "Iberia Reborn: Portugal through the lens of Catalan and Galician Nationalism (1850-1950)". In Resina, Joan Ramon (ed.). Iberian Modalities: A Relational Approach to the Study of Culture in the Iberian Peninsula. Liverpool University Press. p. 90. ISBN 1846318335.

- Hargreaves, John (2000). Freedom for Catalonia?: Catalan Nationalism, Spanish Identity and the Barcelona Olympic Games. Cambridge University Press. p. 74. ISBN 0521586151.

- Caparrós, A.; Martínez, D. (22 June 2016). "Compromís y Podemos abren la vía a la "federación" entre Cataluña, Baleares y la Comunidad Valenciana". ABC (in Spanish).

- Melchor, Vicent de; Branchadell, Albert (2002). El catalán: una lengua de Europa para compartir. Univ. Autònoma de Barcelona. p. 37. ISBN 8449022991.

- Fàbrega, Jaume. La cultura del gust als Països Catalans. El Mèdol, 2000, p. 13.

- Flor i Moreno, 2010, p. 135, 262, 324 and 493-494.

- Maseras i Galtés, Alfons «Pancatalanisme. Tesis per a servir de fonament a una doctrina». Renaixement, 21-01-1915, pàg. 53-55.

- "Llei de creació de l'Acadèmia Valenciana de la Llengua - Viquitexts". ca.wikisource.org. Retrieved 23 October 2019.

- "Catalan". Ethnologue. Retrieved 23 October 2019.

- The Valencian Normative Dictionary of the Valencian Academy of the Language states that Valencian is a "romance language spoken in the Valencian Community, as well as in Catalonia, the Balearic Islands, the French department of the Pyrénées-Orientales, the Principality of Andorra, the eastern flank of Aragon and the Sardinian town of Alghero (unique in Italy), where it receives the name of 'Catalan'."

- 20minutos (7 January 2008). "Otra sentencia equipara valenciano y catalán en las oposiciones, y ya van 13". www.20minutos.es - Últimas Noticias (in Spanish). Retrieved 23 October 2019.

- The Catalan Language Dictionary of the Institut d'Estudis Catalans states in the sixth definition of Valencian that it is equivalent to Catalan language in the Valencian community.

- NacióDigital. "L'AVL reconeix novament la unitat de la llengua | NacióDigital". www.naciodigital.cat (in Catalan). Retrieved 23 October 2019.

- "El PP valencià reconeix la unitat de la llengua per primera vegada a les Corts - Diari La Veu". www.diarilaveu.com (in Catalan). Retrieved 23 October 2019.

- Flor i Moreno, 2009, p. 181

- "L'Acadèmia Valenciana de la Llengua reconeix en el seu diccionari que valencià i català són el mateix". Ara.cat (in Catalan). 31 January 2014. Retrieved 23 October 2019.

- Arnau Gonzàlez i Vilalta (2006) The Catalan Countries Project (1931–1939). Department of Contemporary History, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona.

- Statutes of Valencian Nationalist Bloc Archived 28 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Bloc.ws. Retrieved on 12 September 2013.

- Political project of Republican Left of Catalonia. Esquerra.cat. Retrieved on 12 September 2013.

- El Gobierno valenciano, indignado por la pancarta de 'països catalans' exhibida en el Camp Nou – españa –. Elmundo.es (24 October 2005). Retrieved on 12 September 2013.

- Catalan, the language of eleven million Europeans. Ramon Llull Institute

- Charte en faveur du Catalan. cg66.fr

- "LEY 10/2009, de 22 de diciembre, de uso, protección y promoción de las lenguas propias de Aragon". Retrieved 29 April 2010.

- "La Xarxa Vives s'incorpora als òrgans de govern de l'Institut Ramon Llull" (in Catalan). Xarxa Vives d'Universitats. 22 May 2008. Archived from the original on 29 May 2008.

- Neix la Fundació Ramon Llull. 3cat24.cat (31 March 2008). Retrieved on 12 September 2013.

- (in Catalan) La Generalitat crea la Fundació Ramon Llull a Andorra per projectar la llengua i cultura catalanes. europapress.cat. Europapress.es (18 March 2008). Retrieved on 12 September 2013.

- La Fundació Ramon Llull s'eixampla – VilaWeb. Vilaweb.cat (16 January 2009). Retrieved on 12 September 2013.

- L'Ajuntament de Xeraco aprova una moció del BLOC per a adherir-se a la Fundació Ramon Llull. Valencianisme.Com. Retrieved on 12 September 2013.

- Varios municipios valencianos se suman a la Fundación Ramon Llull para fomentar el catalán. Las Provincias. Lasprovincias.es. Retrieved on 12 September 2013.

- "El Govern balear anuncia que abandona el consorci de l'Institut Ramon Llull" (in Catalan). Institut Ramon Llull. Retrieved 13 June 2017.

- "Federació Llull" (in Catalan). Acció Cultural del País Valencià. Retrieved 13 June 2017.

- "Què és?" (in Catalan). Obra Cultural Balear. Retrieved 13 June 2017.

- Jordà Sánchez, Joan Pau; Amengual i Bibiloni, Miquel; Marimon Riutort, Antoni (2014). "A contracorriente: el independentismo de las Islas Baleares (1976-2011)". Historia Actual Online (in Spanish) (35): 22. ISSN 1696-2060.

- Subirats i Humet, Joan; Vilaregut Sáez, Ricard (2012). "El debat sobre la independència a Catalunya. Causes, implicacions i reptes de futur". Anuari del Conflicte Social (in Catalan). University of Barcelona. ISSN 2014-6760.

- Ridaura Martínez, María Josefa (2016). "El proceso de independencia de Cataluña: su visión desde la Comunidad Valenciana". Teoría y Realidad Constitucional (in Spanish) (37): 384.

- Valenti Puig Archived 24 February 2005 at the Wayback Machine. Joanducros.net. Retrieved on 12 September 2013.

- Crameri, Kathryn (2008). "Catalonia". In Guntram H. Herb; David H. Kaplan (eds.). Nations and Nationalism: A Global Historical Overview. 4. ABC-CLIO. p. 1546. ISBN 978-1-85109-907-8.

- Assier-Andrieu, Louis (1997). "Frontières, culture, nation. La Catalogne comme souveraineté culturelle". Revue européenne des migrations internationales. 13 (3): 33. ISSN 1777-5418.

- "Duran ve un error hablar de 'Països Catalans' porque solivianta a muchos valencianos". La Vanguardia. 15 June 2012.

- Gómez López-Egea, Rafael (2007). "Los nuevos mitos del nacionalismo expansivo" (PDF). Nueva Revista. 112: 70–82. ISSN 1130-0426.

- Corral, José Luis (30 August 2015). "Cataluña, Aragón y los países catalanes". El Periódico de Aragón.

- Germà Bel; Germa Bel i Queralt (2015). Disdain, Distrust and Dissolution: The Surge of Support for Independence in Catalonia. Sussex Academic Press. p. 81. ISBN 978-1-84519-704-9.

- Núñez Seixas, Xosé Manoel (2010). "The Iberian Peninsula: Real and Imagined Overlaps". In Tibor Frank; Frank Hadler (eds.). Disputed Territories and Shared Pasts: Overlapping National Histories in Modern Europe. Basingstoke: Palgrave. p. 346.

- Valencia local elections 2007 accessed 27 July 2009

- Datos Electorales – Elecciones Autonómicas de 2007. cortsvalencianes.es

- El difícil salto de Esquerra Republicana. Elpais.com (30 May 2009). Retrieved on 12 September 2013.

- Bloc Nacionalista Valencià Archived 28 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Bloc.ws. Retrieved on 12 September 2013.

- "Casi el 65% de los valencianos opina que su lengua es distinta al catalán, según una encuesta del CIS". La Vanguardia (in Spanish). 19 December 2004.

- Wheeler 2003, p. 207.

- Generalitat Valenciana. "Barómetro de abril 2014" (PDF).

- Caparrós, Alberto (3 May 2015). "Mas inyecta cuatro millones en dos años para fomentar el catalanismo en Valencia". ABC (in Spanish). Retrieved 2 May 2017.

- Eleccions al Parlament de les Illes Balears. contingutsweb.parlamentib.es (8 June 2007)

- "El Ple aprova defensar l'autonomia del Parlament". Parlament de les Illes Balears (in Catalan). 10 December 2013. Archived from the original on 13 December 2013. Retrieved 17 June 2017.

- "El Parlament balear aprova que 'els Països Catalans no existeixen'". e-notícies (in Catalan). 10 December 2013.

- NacióDigital. "Carlo Sechi: "Ens sentim catalans, però som part de la nació sarda" | NacióDigital". www.naciodigital.cat (in Catalan). Retrieved 31 January 2020.

- Constitución Española en inglés. constitucion.es

- Hadden, Gerry (23 November 2012). "No Independence Fever Among French Catalans". PRI.

- Trelawny, Petroc (24 November 2012). "Catalonia vote: The French who see Barcelona as their capital". BBC.

- Thépot, Stéphane (11 September 2016). "Oui au Pays catalan ou non à l'Occitanie ?". Le Point.

- "Le mouvement Oui au Pays Catalan présent aux législatives". L'Indépendant. 29 January 2017.

- "Manifestation à Perpignan pour commémorer la séparation de la Catalogne en 1659". France 3 Occitanie (in French). Retrieved 18 February 2020.

- L'Acadèmia aprova per unanimitat el Dictamen sobre els principis i criteris per a la defensa de la denominació i l'entitat del valencià. Acadèmia Valenciana de la Llengua

Bibliography

- Assier-Andrieu, Louis (1997). "Frontières, culture, nation. La Catalogne comme souveraineté culturelle". Revue européenne des migrations internationales. 13 (3): 29–46. ISSN 1777-5418.

- Bel, Germà (2015). Disdain, Distrust and Dissolution: The Surge of Support for Independence in Catalonia. Sussex Academic Press. ISBN 9781782841906.

- Crameri, Kathryn (2008). "Catalonia". In Guntram H. Herb y David H. Kaplan (ed.). Nations and Nationalism: A Global Historical Overview. 4. ABC-CLIO. pp. 1536–1548. ISBN 978-1-85109-907-8.

- Gómez López-Egea, Rafael (2007). "Los nuevos mitos del nacionalismo expansivo" (PDF). Nueva Revista. 112: 70–82. ISSN 1130-0426.

- Jordà Sánchez, Joan Pau; Amengual i Bibiloni, Miquel; Marimon Riutort, Antoni (2014). "A contracorriente: el independentismo de las Islas Baleares (1976-2011)". Historia Actual Online (35): 22. ISSN 1696-2060.

- Mercadé, Francesc; Hernández, Francesc; Oltra, Benjamín. Once tesis sobre la cuestión nacional en España. Barcelona: Anthropos. ISBN 84-85887-24-7.

- Núñez Seixas, Xosé Manoel (2010). "The Iberian Peninsula: Real and Imagined Overlaps". In Tibor Frank & Frank Hadler (ed.). Disputed Territories and Shared Pasts: Overlapping National Histories in Modern Europe (PDF). Basingstoke: Palgrave. pp. 329–348. ISBN 978-0230500082.

- Wheeler, Max (2003). "5. Catalan". The Romance Languages. London: Routledge. pp. 170–208. ISBN 0-415-16417-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Atles dels Països Catalans. Barcelona: Enciclopèdia Catalana, 2000. (Geo Estel. Atles) ISBN 84-412-0595-7.

- Burguera, Francesc de Paula. És més senzill encara: digueu-li Espanya (Unitat 3i4; 138) ISBN 84-7502-302-9.

- Fuster, Joan. Qüestió de noms. (Online in Catalan)

- Geografia general dels Països Catalans. Barcelona: Enciclopèdia Catalana. 1992–1996. 7 v. ISBN 84-7739-419-9 (o.c.).

- González i Vilalta, Arnau. La nació imaginada: els fonaments dels Països Catalans (1931–1939). Catarroja: Afers, 2006. (Recerca i pensament; 26)

- Grau, Pere. El panoccitanisme dels anys trenta: l'intent de construir un projecte comú entre catalans i occitans. El contemporani, 14 (gener-maig 1998), p. 29–35.

- Guia, Josep. És molt senzill, digueu-li "Catalunya". (El Nom de la Nació; 24). ISBN 978-84-920952-8-5 (Online in Catalan -PDF)

- Història: política, societat i cultura als Països Catalans. Barcelona: Enciclopèdia Catalana, 1995–2000. 13 v. ISBN 84-412-2483-8 (o.c.).

- Mira, Joan F. Introducció a un país. València: Eliseu Climent, 1980 (Papers bàsics 3i4; 12) ISBN 84-7502-025-9.

- Pérez Moragón, Francesc. El valencianisme i el fet dels Països Catalans (1930–1936), L'Espill, núm. 18 (tardor 1983), p. 57–82.

- Prat de la Riba, Enric. Per Catalunya i per l'Espanya Gran.

- Soldevila, Ferran. Què cal saber de Catalunya. Barcelona: Club Editor, 1968. Amb diverses reimpressions i reedicions. Actualment: Barcelona: Columna: Proa, 1999. ISBN 84-8300-802-5 (Columna). ISBN 84-8256-860-4 (Proa).

- Stegmann, Til i Inge. Guia dels Països Catalans. Barcelona: Curial, 1998. ISBN 84-7256-865-2.

- Ventura, Jordi. Sobre els precedents del terme Països Catalans, taken from "Debat sobre els Països Catalans", Barcelona: Curial..., 1977. p. 347–359.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Catalan Countries. |

- Catalan Countries in the English version of the Catalan Hiperencyclopedia.

- Lletra. Catalan Literature Online

- The Spirit of Catalonia. 1946 book by Oxford Professor Dr. Josep Trueta

- Catalan Countries