Owens Lake

Owens Lake is a mostly dry lake in the Owens Valley on the eastern side of the Sierra Nevada in Inyo County, California. It is about 5 miles (8.0 km) south of Lone Pine, California. Unlike most dry lakes in the Basin and Range Province that have been dry for thousands of years, Owens held significant water until 1913, when much of the Owens River was diverted into the Los Angeles Aqueduct, causing Owens Lake to desiccate by 1926.[2] Today, some of the flow of the river has been restored, and the lake now contains some water. Nevertheless, as of 2013, it is the largest single source of dust pollution in the United States.[3]

| Owens Lake | |

|---|---|

Image of the Owens Valley from the International Space Station – oriented top = true west. | |

Owens Lake | |

| Location | Sierra Nevada Inyo County, California, United States |

| Coordinates | 36.4332°N 117.9509°W |

| Type | Flat |

| Primary inflows | Owens River Natural springs and wells |

| Basin countries | United States |

| Max. length | 17.5 mi (28.2 km) |

| Max. width | 10 mi (16 km) |

| Max. depth | 3 ft (0.91 m) |

| Surface elevation | 3,556 ft (1,084 m)[1] |

| References | GNIS feature ID 272820[1] |

History

Owens Lake was given its present name by the explorer John C. Fremont, in honor of one of his guides, Richard Owens.[4] Richard Owens however never stepped foot in the valley. The lakes original name, given by the Nüümü (Owens Valley Paiute), is Patsiata.[5]

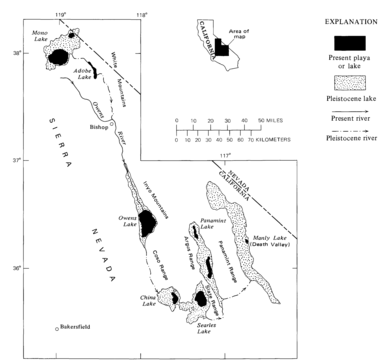

Before the diversion of the Owens River, Owens Lake was up to 12 miles (19 km) long and 8 miles (13 km) wide, covering an area of up to 108 square miles (280 km2). In the last few hundred years the lake had an average depth of 23 to 50 feet (7.0 to 15.2 m), and sometimes overflowed to the south, after which the water would flow into the Mojave Desert.[2] In 1905, the lake's water was thought to be "excessively saline."[6] It is thought that in the late Pleistocene about 11–12,000 years ago Owens Lake was even larger, covering nearly 200 square miles (520 km2) and reaching a depth of 200 feet (61 m). The increased inflow from the Owens River, from melting glaciers of the post-Ice Age Sierra Nevada, caused Owens Lake to overflow south through Rose Valley into another now-dry lakebed China Lake, in the Indian Wells Valley near Ridgecrest, California. After the glaciers melted, the lake waters receded. This accelerated with human exploitation of the lake, even before the Los Angeles Aqueduct was built, because Owens Valley farmers had already appropriated most of the Owens River's tributaries' flow, causing the lake level to drop slightly each year.

Starting in 1913, the river and streams that fed Owens Lake were diverted by Los Angeles Department of Water and Power (LADWP) into the Los Angeles Aqueduct, and the lake level started to drop quickly.[7] As the lake dried, soda processing at nearby Keeler, California, switched from relatively cheap chemical methods to more expensive physical ones. The Natural Soda Products Company sued the city of Los Angeles and built a new plant with a $15,000 settlement. A fire destroyed this plant shortly after it was built, but the company rebuilt it on the dry lakebed in the 1920s.

During the unusually wet winter of 1937, LADWP diverted water from the aqueduct into the lakebed, flooding the soda plant. Because of this, the courts ordered the city to pay $154,000. After an unsuccessful appeal to the state supreme court in 1941, LADWP built the Long Valley Dam, which impounded Lake Crowley for flood control.[7]

Current conditions

The lake is currently a large salt flat whose surface is made of a mixture of clay, sand, and a variety of minerals including halite, burkeite, mirabilite, thenardite, and trona. In wet years, these minerals form a chemical soup in the form of a small brine pond within the dry lake. When conditions are right, bright pink halophilic (salt-loving) archaea spread across the salty lakebed. Also, on especially hot summer days when ground temperatures exceed 150° F (66 °C), water is driven out of the hydrates on the lakebed creating a muddy brine. More commonly, periodic winds stir up noxious alkali dust storms that carry away as much as four million tons (3.6 million metric tons) of dust from the lakebed each year, causing respiratory problems in nearby residents.[7][8] The dust includes carcinogens, such as cadmium, nickel and arsenic.[9]

Current management

The LADWP and the California State Lands Commission own most of the Owens Lake bed, though a few small parcels along the historic western shoreline are privately owned.[10] In 2004, the California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW) acquired a 218-acre (88 ha) parcel at the foot of Owens Lake. Designated the Cartago Wildlife Area in 2007, it is one of the few remaining spring and wetland areas on the shore of Owens Lake.[11] CDFW is using mitigation funds from CalTrans to enhance habitat.

As part of an air quality mitigation settlement, LADWP is currently shallow flooding 27 square miles (69.9 km2) of the salt pan to try to help minimize alkali dust storms and further adverse health effects. There is also about 3.5 square miles (9.1 km2) of managed vegetation being used as a dust control measure. The vegetation consists of saltgrass, which is a native perennial grass highly tolerant of the salt and boron levels in the lake sediments.[12] Gravel covers are also used.[13]

Ecology

This once-blue saline lake was an important feeding and resting stop for millions of waterfowl each year. During a visit to Owens Lake in 1917 Joseph Grinnell from the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology in Berkeley reported "Great numbers of water birds are in sight along the lake shore--avocets, phalaropes, ducks. Large flocks of shorebirds in flight over the water in the distance, wheeling about show in mass, now silvery now dark, against the gray-blue of the water. There must be literally thousands of birds within sight of this one spot."

Owens Lake is still recognized as an Important Bird Area in California by the National Audubon Society.[10] At the shore, a chain of wetlands, fed by springs and artesian wells, keep part of the former Owens Lake ecosystem alive. Snowy plovers nest at Owens along with several thousand snow geese and ducks. As a result of current dust mitigation efforts, shallow flooding of the lakebed has created both shallow and deeper (about 3 feet (0.9 m) deep) habitats on the lakebed.[14] This water, although seasonally applied, is helping to buoy the lake's ecosystem causing hope in conservationists that an expanded shallow flooding program could do even more. There are no serious plans, however, to restore Owens to anything resembling a conventional lake.[7]

On April 19, 2008, the Eastern Sierra Audubon Society, Audubon California, and the Owens Valley Committee held the first lake-wide survey of the bird populations of Owens Lake. Volunteers recorded a total of 112 avian species and 45,650 individual birds — the highest total number of birds ever officially recorded at Owens Lake. Volunteers identified 15 species of waterfowl (ducks and geese) and 22 species of shorebirds. The highest totals for individuals of a species included 13,873 California gulls (an inland nester at Mono Lake and elsewhere); 9,218 American avocets; 1,767 eared grebes; 13,826 peeps or small sandpipers such as dunlin, western and least sandpipers; and 2,882 individual ducks.[12]

Local industry

Cerro Gordo Mines

The town of Cartago, below the Sierra Nevada near present-day Olancha, California, was the western shipping port for the Cerro Gordo Mines production and transported goods across Owens Lake with the northern ports of Swansea and Keeler directly below the mines. From Cartago a barge-like vessel, the Bessie Brady, was launched in 1872, which cut the three-day freight journey around the lake down to three hours.[15]

Much of the freight it carried was silver and lead bullion from the Cerro Gordo mines, which at their height were so productive that the bars of the refined metals waited in large stacks before twenty-mule team teamsters could haul it to Los Angeles. The trying three-week (one way) journey improved after the formation of the Cerro Gordo Freighting Company, run by ancestors of regional historian Remi Nadeau who has written of this period.

The town of Keeler, below the Inyo Mountains on the former north shore, replaced Swansea as the shipping port for the mines after the 1872 Lone Pine earthquake. In the 1870s it had a population of 5,000 people as the center of trade for the Cerro Gordo mines.

The Cottonwood Charcoal Kilns, traditional stone masonry 'beehive' charcoal kilns, were built to transform wood from trees in Cottonwood Canyon above the lake into charcoal, to feed the Cerro Gordo mines' silver and lead smelters across the lake at Swansea. The ruins are located on the southern side of the lakebed near Cartago. They were similar to the nearby Panamint Charcoal Kilns near Death Valley. The kilns are identified as California Historical Landmark #537.[16]

Other enterprises

In 1879 silver mining ended, but Keeler was saved when the Carson and Colorado Railroad built narrow-gauge rail tracks to the town. It then became a soda, salt, and marble shipping center until 1960. The rail line had been sold to Southern Pacific Railroad in 1900. Keeler's current population is around 50 people and continues in decline.

In the 20th century the Clark Chemical Company operated on the northwestern shore at Bartlett, with evaporation ponds for lake brine and a plant to extract its chemicals.

Mineral extraction plants around the lake:[17]

- Inyo Development Company, 1887-1920

- Natural Soda Products Company/Michigan Alkali Company/Wyandotte Chemical Corporation, 1912-1953

- California Alkali Company/Inyo Chemical Company, 1917-1932

- Pacific Alkali/Columbia-Southern Chemical Corp./Pittsburgh Plate Glass, 1928-1968

- Permanente Metals Corporation, 1947-1950

- Morrison and Weatherly Chemical Corporation (M&W)/Lake Minerals Corporation (LMC)/Cominco American Inc./Owens Lake Soda Ash Company (OLSAC)/U.S. Borax/Rio Tinto Minerals, 1962–present. Rio Tinto Minerals has mineral lease renewals through 2048.[18]

Filmography

Numerous Western films have been shot by Owens Lake, including Westward Ho (1935) starring John Wayne, Maverick (1994) starring Mel Gibson, Riders of the Dawn (1937), Across the Plains (1939), Stage to Tucson (1951), From Hell to Texas (1958) and Nevada Smith (1966).[19]

Other films that had scenes shot at Owens Lake or the nearby Alabama Hills where Owens Lake is visible includes Top Gun (1986) starring Tom Cruise, and Tremors (1990) starring Kevin Bacon.[20]

Public access

The Cartago Wildlife Area continues to develop as a wildlife-viewing area for the public. The site is open year-round for viewing numerous bird species attracted to the ponds and wetlands as well as the ruins of a historic soda ash plant from the World War I era and the 1920s.[12]

Surroundings from Earth orbit

See also

- Owens River course

- List of lakes in California

- Los Angeles Aqueduct

- California Water Wars

- List of drying lakes

References

Notes

- U.S. Geological Survey (19 January 1981). "Feature Detail Report: Owens Lake". Geographic Names Information System (GNIS). U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved 2009-03-26.

- Reheis, Marith C. (2006-04-11). "Owens (Dry) Lake, California: A Human-Induced Dust Problem". Impacts of Climate Change and Land Use in the Southwestern United States. U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved 2010-06-03.

- Siegler, Kirk (2013-03-11). "Owens Valley Salty As Los Angeles Water Battle Flows Into Court". NPR.

- M. Morgan Estergreen (1962). Kit Carson: A Portrait in Courage. University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 126–144. ISBN 978-0758117656.

- Indigenous Women Hike. Personal communication. Dec 28, 2019.

- Gilman, D. C.; Peck, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905). . New International Encyclopedia (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead.

- "Bledsoe Collection 1908-1933, Los Angeles Department of Water and Power". Scenic Views – Owens Valley.

- Knudson, Tom (January 5, 2014). "Outrage in Owens Valley a century after L.A. began taking its water". Sacramento Bee. Retrieved 21 October 2014.

- Owens Lake Valley PM10 Planning Area Screening Ecological Risk Assessment of Proposed Dust Control Measures (PDF). 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2015-07-28.

- "National Audubon Society -> Important Bird Areas -> Site Profile". netapp.audubon.org. 2016-09-12. Retrieved 2015-07-24.

- "Cartago Wildlife Area". www.wildlife.ca.gov. Retrieved 2015-07-24.

- Prather, Michael (Winter 2008). "Owens Lake is coming back to wildlife" (PDF). Rainshadow Newsletter. 4 (2). Owens Valley Committee. p. 5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2009-02-01.

- "History - Owens Valley, California Air Actions | Pacific Southwest | US EPA". www.epa.gov. Retrieved 2015-07-28.

- Sahagun, Louis (November 14, 2014) "New dust-busting method ends L.A.'s longtime feud with Owens Valley" Los Angeles Times

- Parsons, Dana (March 24, 1988) "Digging Up a Mythtery : Under the Floor of Owens Lake, a Fabled Silver Cache Awaits Discovery, So They Say" Los Angeles Times

- "California Historical Landmarks - Inyo County". California State Parks Department. State of California. Retrieved 19 April 2011.

- "Minerals and Mining". Carson & Colorado Railway. Archived from the original on 2015-07-14.

- "U.S. Borax Inc. Owens Lake Operations". Owens Lake Bed Master Project. Archived from the original on 2015-10-18.

- Schneider, Jerry L. (2016). Western Filming Locations California Book 6. CP Entertainment Books. Page 80. ISBN 9780692722947.

- Lone Pine Film History Museum, http://www.lonepinefilmhistorymuseum.org/film-history

Bibliography

- Sahagun, Louis. "Dammed by Past, Owens River Flows Again". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on December 8, 2006.

- Sharp, Glazner (1997). Geology Underfoot in Death Valley and Owens Valley. Missoula: Mountain Press Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-87842-362-0.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Owens Lake. |

- The Owens Valley Committee: Owens Lake

- Owens (Dry) Lake, California: A Human-Induced Dust Problem

- Owens Lake Dust Bedevils Keeler

- David Maisel's "The Lake Project"

- "The Eternal Dustbowl" March 22, 2006 feature article in the LA Weekly on the controversy surrounding the Los Angeles Dept. of Water and Power's environmental mitigation efforts at Owens Lake, written by Jeffrey Anderson, with photographs by Claudio Cambon.

- Birds of the Owens Lake

- Minerals and Mining