Oregon Ballot Measures 37 and 49

Oregon Ballot Measure 37 is a controversial land-use ballot initiative that passed in the U.S. state of Oregon in 2004 and is now codified as Oregon Revised Statutes (ORS) 195.305. Measure 37 has figured prominently in debates about the rights of property owners versus the public's right to enforce environmental and other land use regulations. Voters passed Measure 49 in 2007, substantially reducing the impact of Measure 37.[1]

Content of the proposal

The law enacted by Measure 37 allows property owners whose property value is reduced by environmental or other land use regulations to claim compensation from state or local government. If the government fails to compensate a claimant within two years of the claim, the law allows the claimant to use the property under only the regulations in place at the time he/she purchased the property.[2] Certain types of regulations, however, are exempt from this.

Legal context

Advocates for Measure 37 have described it as a protection against "regulatory taking," a notion with roots in an interpretation of the United States Constitution.

The Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution ends as follows:

…nor shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation.

That phrase provides the foundation for the government power of eminent domain, and requires compensation for governmental appropriations of physical property. It has occasionally been used to require compensation for use restrictions that deprive the owner of any economically-viable use of land. See the 1922 United States Supreme Court case Pennsylvania Coal Co. v. Mahon.)[3]

The advocates of Measure 37 employed a more expansive interpretation of the concept of regulatory taking than required by the Supreme Court, considering any reduction in a piece of property's value - for instance, a reduction resulting from an environmental regulation - to require compensation to the owner.[4]

Measure 37 was ruled unconstitutional in a 2005 circuit court decision,[5] but the Oregon Supreme Court reversed that decision,[6] ruling that the law was not unconstitutional, and noting that the Court was not empowered to rule on its efficacy:

Whether Measure 37 as a policy choice is wise or foolish, farsighted or blind, is beyond this court's purview.

Political context

Oregon

In the early 1970s, Senate Bill 100 and Portland's 1972 Downtown Plan established bold guidelines for the regulation of land use. Oregon became known for its land use planning. While some Oregonians take great pride in that, others consider themselves victimized by government oversight. The strong 2004 passage (61%) of Measure 37 is considered a political backlash to that legacy of regulation,[7] and follows several other unsuccessful efforts to restrict land use regulation:

- Oregon Ballot Measure 65 (1998) and Oregon Ballot Measure 2 (2000) sought to restrict the Legislature's ability to regulate land use; both measures failed.

- Oregon Ballot Measure 7 (2000) was similar to Measure 37. It was approved, but struck down by the Oregon Supreme Court.

- Measure 39, which passed in 2006, restricted the use of eminent domain. It was promoted by Oregonians In Action as a "natural extension" of Measure 37, and passed with very little opposition.[8]

- Measure 49, passed in 2007, virtually replaces Measure 37. It eliminated nearly every Measure 37 provision designed to allow pre-regulation use of one's own property, as well as all compensation provisions. It also addresses questions about transferability, and offered to fast-track some smaller Measure 37 claims under post 2007 land use regulations.

Nationwide

The state of Washington's legislature referred Initiative 164 (also known as Referendum 48) to the ballot in 1995. This "regulatory takings" bill was similar to Measure 37 in its restriction of local governments' ability to regulate land use. The bill was widely criticized, and was not approved by voters.[9]

In 2006, voters in six western states considered ballot initiatives similar to Oregon's 2004 Measure 37.[10] All states except Arizona rejected the initiatives.[11]

Arizona's initiative combined the land use/regulatory taking issue central to Oregon Ballot Measure 37 with a restriction on eminent domain (similar to Oregon Ballot Measure 39 (2006)). The Arizona initiative's proponents focused their arguments almost exclusively on the less controversial eminent domain portion of the initiative.[12]

The Nevada initiative also combined the two issues. The regulatory taking portions of Nevada's initiative (i.e., those most similar to Oregon's Measure 37) were removed by the state Supreme Court, and voters approved the remaining restrictions on eminent domain. The Nevada initiative will be reviewed in the next election.

This surge in related initiatives reflects the rising influence of political activists who coordinate the production and advocacy of state ballot initiatives on a national level. Many of the ballot initiatives in the following table (in numerous states) have been financed by New York libertarian Howie Rich and groups he is involved with, most notably Americans for Limited Government.

2006 initiatives restricting regulation of land use and condemnation:

| state | measure title | passed? | incl. eminent domain component? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arizona | Prop. 207 | passed | yes |

| California | Prop. 90 | defeated | yes |

| Idaho | Prop 2 | defeated[13] | yes |

| Montana | Init. 154 | invalidated by court[14] | yes |

| Nevada | State Ques. 6 | invalidated by court[15][16] | yes; that component passed |

| Washington | I-933[17] | defeated | no |

Legislative text

The following are the first three sections of the law; for a complete version, see Oregon State Land Use site.

- If a public entity enacts or enforces a new land use regulation or enforces a land use regulation enacted prior to the effective date of this amendment that restricts the use of private real property or any interest therein and has the effect of reducing the fair market value of the property, or any interest therein, then the owner of the property shall be paid just compensation.

- Just compensation shall be equal to the reduction in the fair market value of the affected property interest resulting from enactment or enforcement of the land use regulation as of the date the owner makes written demand for compensation under this act.

- Subsection (1) of this act shall not apply to land use regulations:

- Restricting or prohibiting activities commonly and historically recognized as public nuisances under common law. This subsection shall be construed narrowly in favor of a finding of compensation under this act;

- Restricting or prohibiting activities for the protection of public health and safety, such as fire and building codes, health and sanitation regulations, solid or hazardous waste regulations, and pollution control regulations;

- To the extent the land use regulation is required to comply with federal law;

- Restricting or prohibiting the use of a property for the purpose of selling pornography or performing nude dancing. Nothing in this subsection, however, is intended to affect or alter rights provided by the Oregon or United States Constitutions; or

- Enacted prior to the date of acquisition of the property by the owner or a family member of the owner who owned the subject property prior to acquisition or inheritance by the owner, whichever occurred first.

Support for Measure 37

Arguments in support supplied by individuals and interest groups for inclusion in the voter's pamphlet for Measure 37 are found here.

Supporters argue that Measure 37 provided protection of the value of property by insuring that new legislation doesn't decrease property values or limit development possibilities. Timber companies and real estate developers were the most prominent supporters (and the primary funders) of Measure 37,[18] presumably because environmental and other land use regulations would impact them most directly.

Measure 37's sponsor, Oregonians In Action, and various supporters drummed up support during the 2004 election using the case of Dorothy English, a then-92-year-old woman, as a cause célèbre. Enacted zoning regulations prevented English from dividing her land into pieces that could go to each of her children.[19]

Opposition to Measure 37

Arguments in opposition supplied by individuals and interest groups for inclusion in the voter's pamphlet for Measure 37 are found here.

The following are major arguments advanced against Measure 37:

- Given that a large portion of a property's value is created by legislation (e.g. laws providing for public roads, sewers, electrical lines, parks, etc.), it is unreasonable to require the government to compensate property owners for any additional legislation which might restrict property use in the name of the public good [20]

- Measure 37 undermined the property rights of neighbors. Owners who purchased homes in areas zoned single family residential, or wineries in areas zoned exclusively agricultural, lost the value of their property as Measure 37 claimants were authorized to build large subdivisions, gravel mines, and hotels next to their land.[1]

- Environmental impact. Since the government will rarely be able to fund the measure, many property owners, especially major developers, will be able to ignore environmental legislation enacted to protect the public good. This has already led to significant blows to state efforts to protect endangered species.[21] In fact, to date existing land use restrictions have been waived in every claim filed under Measure 37.

- Questionable legality. Rulings by The Supreme Court have deferred to the State and local legislative authorities in determining what constitutes a legitimate exercise of protection of the public interest, as in the 5-4 "Kelo Decision" which allowed takings of private property when a significant public good could be demonstrated. On this ground, existing environmental legislation, even if a 'taking' under the fifth amendment, ought to be allowed as a reasonable expression of the public good.

- As more claims are being filed, many voters are feeling the impact of unregulated development.[22]

- The legislation imposes a large burden on the taxpayers, because there is no provision for funding any payoffs for claims under Measure 37 within the Measure's text. Therefore, all funds must be taken from the general budget of the municipality, which includes funding for schools, roads, health clinics, etc. In order to maintain the existing levels of protection for their communities, taxpayers would have to fund billions of dollars in compensation to landowners.

- The legislation is incomplete, in that it fails to dictate a method for determining property value when a claim is filed or evaluated.[23]

- The legislation is deceptive, in that it coerces governments into altering land use laws without debating them on their merits.[23]

- The campaign for the ballot measure was deceptive, claiming that the law would apply mainly to private property owners (like spokeswoman Dorothy English), when in fact the majority of claims have come from large-scale developers. One of the earliest large claims was brought by a timber company from another state.[24]

Impact

As of March 12, 2007, 7,562 Measure 37 claims for compliance payments or land use waivers had been filed spanning 750,898 acres (3,038.78 km2) statewide in Oregon.[25]

The claims filed included mobile home parks in sacred native burial grounds, shopping malls in farmland, and gravel pit mines in residential neighborhoods. There are no provisions in the law that public notice must be provided to neighboring property owners when a claim is filed. Because municipalities can not afford the billions in compensation, the laws were waived in every case but one.[22]

Claims filed in Portland, Oregon, by December 4, 2006, totalled over $250 million. Many of these claims were filed by major area land developers.[26]

Outside of Oregon, some contend that Measure 37 may have decreased support for national anti-urban sprawl legislation.[18]

Specific cases

The owners of Schreiner's Iris Gardens filed a claim in late 2006, demanding either $9.5 million or the right to subdivide their 400 acres (1.6 km2). They assert that they have no intention of changing the use of the property, but want to keep options open for the future.[27]

John Benton, a Hood River County fruit farmer, filed a Measure 37 claim, demanding either $57 million or the right to build 800 houses on his 210 acres (0.85 km2) of property. Neighboring farmers objected, due to the significant impact they anticipated such a change would bring to their community.[18]

In the fall of 2006, the Palins, a Prineville couple, filed a Measure 37 claim, demanding either $200,000 or the right to develop their property, which is on a scenic portion of rimrock clearly visible from the city. The city did its own appraisal of the property's potential value, and offered $47,000. This was the first case where the government offered money instead of a waiver of land use restrictions, and highlights the Measure's lack of a clear process for determining the value associated with a claim.[28]

In a January 15, 2007 article, a statewide newspaper highlighted a Measure 37-based claim in Hood River County, in which land owners aim to develop a parcel of rural land eight times the size of the city of Hood River:

As negotiations begin, Hood River is emerging as the perfect case study. No other county's Measure 37 dynamics speak so directly to Oregon's changing economy and lifestyle.[29]

Measure 49

| Measure 49 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Modifies Measure 37; clarifies right to build homes; limits large developments; protects farms, forests, groundwater. | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Source: Oregon Secretary of State [30] | ||||||||||||||||||||||

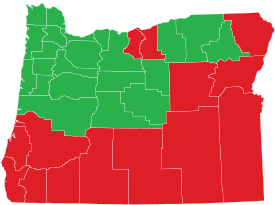

In 2007, the Oregon legislature placed Measure 49 on the November 6, 2007 special election ballot. It passed with 62% in favor.[31] The measure overturns and modifies many of the provisions of Measure 37.[32] The Legislature stated that it would restrict the damaging effects of Measure 37 by limiting some of the development that measure permitted.[33]

This measure protects farmlands, forestlands and lands with groundwater shortages in two ways.

First, subdivisions are not allowed on high-value farmlands, forestlands and groundwater-restricted lands. Claimants may not build more than three homes on such lands.

Second, claimants may not use this measure to override current zoning laws that prohibit commercial and industrial developments, such as strip malls and mines, on land reserved for homes, farms, forests and other uses.

A record 117 paid arguments on Measure 49 appeared in the voter's pamphlet for that election, most favoring it.[34]

Measure 49 passed by an even greater margin than Measure 37 had. The impact of the law is as follows. The measure no longer authorizes challenges to restrictions on industrial or commercial uses of property. In addition, claimants must prove their losses by presenting appraisals of the property one year before and one year after the enactment of the regulation. For land use restrictions enacted before 2007, the restriction may only be waived to permit the claimant to build one to three homes on their land, or up to 10 homes if the property is not high value agricultural land and they can show that the waiver is necessary to restore the appraised value of the property.[35]

References

- Bethany R. Berger, What Owners Want and Governments Do: Lessons from the Oregon Experiment, 78 Fordham L. Rev. 1291 (2009), https://ssrn.com/abstract=1408343

- http://www.lcd.state.or.us/LCD/MEASURE37/index.shtml

- FindLaw: U.S. Constitution: Fifth Amendment: Annotations pg. 14 of 16

- Regulatory Takings

- "Judge rules Measure 37 unconstitutional". Portland Business Journal. October 14, 2005. Retrieved 2007-01-30.

- MacPherson v. Department of Administrative Services, 340 Or. 117, 130 P.3d 308 (2006) Archived September 25, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- Turf: The Green Dream: Endangered Ecotopia (Seattle Weekly)

- Oppenheimer, Laura (September 25, 2006). "Foes of land takings widen aim". The Oregonian. Retrieved 2006-12-29.

- Olsen, Ken (May 29, 1995). "Legislature votes to hamstring Washington state". High Country News. Archived from the original on September 28, 2007. Retrieved January 20, 2007.

- de Place, Eric (October 12, 2006). "Prop. 207 supporters should ask how Oregon's 37 measures up". Tucson Citizen. Retrieved 2006-12-22.

- "Oregon's Neighbors Say "NO!" to Measure 37-Style Initiatives" (Press release). 1000 Friends of Oregon. November 8, 2006. Retrieved 2007-01-17.

- 2006 Ballot Propositions & Judicial Performance Review Archived December 14, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- 2006 General Results statewide Archived 2006-12-13 at the Wayback Machine

- Dennison, Mike (October 27, 2006). "Election 2006 / Initiative ruling stands". Missoulian. Retrieved 2006-12-26.

- State of Nevada 2006 Official Statewide General Election Results Archived December 18, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- "Nevada Ballot Measures, 2006". Project Vote Smart. Archived from the original on 2006-12-14. Retrieved 2007-01-21.

- Pryne, Eric (October 23, 2006). "Measure 37 and I-933: How they stack up". The Seattle Times.

- Blaine Harden (February 28, 2005). "Anti-Sprawl Laws, Property Rights Collide in Oregon". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2007-01-12.

- Sam Lowry (January 12, 2006). "Measure 37 in Court: There's Got To Be A Better Way". NewWest. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved 2007-01-12.

- Rypkema, Donovan (June 13, 2001). "Property Rights and Public Values" (PDF). Georgetown Environmental Law & Policy Institute. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 27, 2007. Retrieved 2007-01-22.

- John D. Echeverria (October 11, 2005). "The House takes an ax to the Endangered Species Act". Headwater News. Archived from the original on April 22, 2007. Retrieved 2007-01-17.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on September 8, 2006. Retrieved October 18, 2006.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Editorial (October 30, 2006). "Prineville tries to save its scenic rimrock vista". The Oregonian. Retrieved 2006-12-22.

- Editorial (December 4, 2006). "Revealing the true game behind Measure 37". The Oregonian. Retrieved 2006-12-22.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on February 8, 2007. Retrieved February 11, 2007.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Nick Budnick (December 19, 2006). "Measure 37 hammers city". Portland Tribune. Retrieved 2013-04-20.

- The Associated Press (October 27, 2006). "Iris grower files Measure 37 claims". The Register Guard. Retrieved 2007-01-16.

- Matthew Pruesch (October 26, 2006). "Prineville offers Measure 37 pay". The Oregonian. Retrieved 2007-01-16.

- Oppenheimer, Laura (January 15, 2007). "Will there be room for pears, paradise under Measure 37?". The Oregonian. Retrieved 2007-01-20.

- Bradbury, Bill (November 6, 2007). "Official Results – November 6, 2007 Special Election" (Website). Elections Division. Oregon Secretary of State. Retrieved December 27, 2008.

- Murphy, Todd (November 6, 2007). "Oregon voters overwhelmingly back Measure 49". Portland Tribune. Retrieved 2013-04-20.

- http://records.sos.state.or.us/ORSOSWebDrawer/Recordpdf/6873597 November 6, 2007, Special Election

- http://records.sos.state.or.us/ORSOSWebDrawer/Recordpdf/6873597 Explanatory Statement

- Hogan, Dave "Voter guide thick with Measure 49 arguments" The Oregonian, September 26, 2007.] Retrieved on October 7, 2007 ]

- Ballot Measure 49, ch. 424, 2007 Or. Laws 1138-1147.

External links

Background on Property Rights

- Georgetown University background on the takings issue

- a "Republican developer type" on property rights from the GELPI site

Oregon specific linkings

- State of Oregon's Measure 37 page

- Full text of Measure 37

- Portland State University project measuring the impact of Measure 37, including searchable index of claims

- Land Use Watch articles about Measure 37 and other land use issues

- Report on impacts of Measure 37

- Measure 37 resources from land use advocates 1000 Friends of Oregon

Political and legal analysis

- report on the context and effects of Measure 37

- list of issues unresolved by MacPherson v. DAS