Operculum (fish)

The operculum is a series of bones found in bony fish that serves as a facial support structure and a protective covering for the gills; it is also used for respiration and feeding.[1]

Anatomy

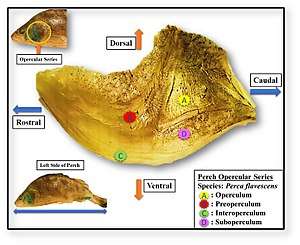

The opercular series contains four bone segments known as the preoperculum, suboperculum, interoperculum and operculum. The preoperculum is a crescent-shaped structure that has a series of ridges directed posterodorsally to the organisms canal pores. The preoperculum can be located through an exposed condyle that is present immediately under its ventral margin; it also borders the operculum, suboperculum, and interoperculum posteriorly. The suboperculum is rectangular in shape in most bony fishy and is located ventral to the preoperculum and operculum components. It is the thinnest bone segment out of the opercular series and is located directly above the gills. The interoperculum is triangular shaped and borders the suboperculum posterodorsally and the preoperculum anterodorsally. This bone is also known to be short on the dorsal and ventral surrounding borders.[2]

Developmental

During development the opercular series is known to be one of the first bone structures to form. In the three-spined stickleback the opercular series is seen forming at around seven days after fertilization. Within hours the formation of the shape is visible and then the individual components are developed days later. The size and shape of the operculum bone is dependent on the organism's location. For example, fresh water threespine sticklebacks form a less dense and smaller opercular series in relation to marine threespine sticklebacks. The marine threespine stickleback exhibits a larger and thicker opercular series. This provides evidence that there was an evolutionary change in the operculum bone. The thicker and more dense bone may have been favored due to selective pressures exerted from the threespine stickleback's environment. The development of the operculuar series has changed dramatically over time. The fossil record of the threespine stickleback provide the ancestral shapes of the operculum bone. Overall, the operculum bone became more triangular in shape and thicker in size over time.[2]

Genes that are essential in the development of the opercular series is the Eda and Pitx1 genes. These genes are known to be a part of the development and loss of armor plates in gnathostomes. The Endothelin1 pathway is thought to be associated with the development of the operculum bone since it regulates dorsal-ventral patterning of the hyomandibular region. Mutations in Edn1-pathway in zebrafish are known to lead to deformities of the opercular series shape and size.[2]

The opercular series is vital in obtaining oxygen. They open as the mouth closes, causing the pressure inside the fish to drop. Water then flows towards the lower pressure across the fish's gill lamellae, allowing some oxygen to be absorbed from the water. In cartilaginous ratfishes, they present soft and flexible opercular flaps. Sharks, rays and relatives such as elasmobranch fishes lack the opercular series. They instead respire through a series of gill slits that perforate the body wall. Without the operculum bone, other methods of getting water to the gills are required, such as ram ventilation, as used by many sharks.

See also

References

- Charles B. Kimmel; Windsor E. Aguirre; Bonnie Ullmann; Mark Currey; William A. Cresko (2008). "Allometric change accompanies opercular shape evolution in Alaskan threespine sticklebacks". Fifth International Conference on Stickleback Behavior and Evolution. 145 (4/5): 669–691. JSTOR 40295944.

- Lane, Jennifer A.; Ebert, Martin (2012). "Revision of Furo muensteri (Halecomorphi, Ophiopsidae) from the Upper Jurassic of Western Europe, with comments on the genus". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 32 (4): 799–819. doi:10.1080/02724634.2012.680325.