Operation Graffham

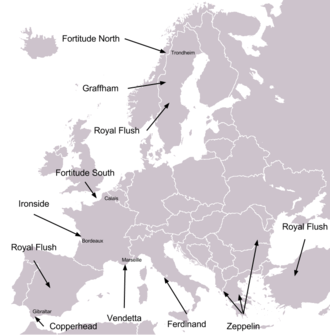

Operation Graffham was a military deception employed by the Allies during the Second World War. It formed part of Operation Bodyguard, a broad strategic deception designed to disguise the imminent Allied invasion of Normandy. Graffham provided political support to the visual and wireless deception of Operation Fortitude North. These operations together created a fictional threat to Norway during the summer of 1944.

| Operation Graffham | |

|---|---|

| Part of Operation Bodyguard | |

Graffham was one of several plans within the overall Bodyguard deception | |

| Operational scope | Political Deception |

| Location | Stockholm, Sweden |

| Planned | February – March 1944 |

| Planned by | London Controlling Section |

| Target | Sweden, German intelligence |

| Date | March – June 1944 |

| Outcome | Failure to outright convince Swedish government of an impending Allied invasion in Norway |

Planning for the operation began in February 1944. In contrast to the other aspects of Bodyguard, Graffham was planned and executed by the British, with no American involvement. Graffham's aim was to convince German intelligence that the Allies were actively building political ties with Sweden, in preparation for an upcoming invasion of Norway. It involved meetings between several British and Swedish officials, as well as the purchase of Norwegian securities and the use of double agents to spread rumours. During the war, Sweden maintained a neutral stance and it was hoped that if the government were convinced of an imminent Allied invasion of Norway this would filter through to German intelligence.

The impact of Graffham was minimal. The Swedish government agreed to few of the concessions requested during the meetings, and few high-level officials were convinced that the Allies would invade Norway. Overall, the influence of Graffham and Fortitude North on German strategy in Scandinavia is disputed.

Background

Operation Graffham formed part of Operation Bodyguard, a broad strategic military deception intended to confuse the Axis high command as to Allied intentions during the lead-up to the Normandy landings. One of the key elements of Bodyguard was Operation Fortitude North, which promoted a fictional threat against Norway via wireless traffic and visual deception. Fortitude North played on German, and particularly Adolf Hitler's, belief that Norway was a key objective for the Allies (although they had earlier considered and rejected the option).[1]

The Allies had previously employed several deceptions against the region (for example Operation Hardboiled in 1942 and Operation Cockade in 1943). As a result, John Bevan, head of the London Controlling Section (LCS) and charged with overall organisation of Bodyguard, was concerned that visual/wireless deception would not be enough to create a believable threat.[2]

Bevan suggested a political deception with the aim of convincing the Swedish government that the Allies intended to invade Norway. During the war Sweden maintained a neutral position, and had relations with both Axis and the Allied nations. It was therefore assumed that if Sweden believed in an imminent threat to Norway this would be passed on to German intelligence.[2] Graffham was envisioned as an extension of existing pressure the Allies were placing on Sweden to end their neutral stance, one example being the requests to end the export of ball bearings (an important component in military hardware) to Germany. By increasing this pressure with additional, false requests, Bevan hoped to further convince the Germans that Sweden was preparing to join the Allied nations.[3]

Planning

On 3 February 1944, the LCS proposed a plan "to induce the enemy to believe that we are enlisting the help of Sweden in connection with the British and Russian contemplated operations against northern Norway in the Spring of this year."[4] The department received approval to move forward with Graffham on 10 February 1944. It would be an entirely British operation with no American involvement (in contrast to the other Bodyguard components). Based on recommendations from the Chiefs of Staff, the LCS outlined seven requests to present to the Swedish government:[2]

- Access to Swedish airspace for the passage of Allied aircraft, including permission for emergency landings

- Access to repair facilities at Swedish airfields for up to 48 hours

- Permission for reconnaissance flights within Swedish airspace

- Collaboration between British and Swedish transport experts to organize transport of equipment across Sweden following German withdrawal

- Permission for Colonel H. V. Thornton (the former military attaché to Sweden) to meet Swedish officials

- Agreement to the purchase of Norwegian securities by the British government

- False wireless traffic between the two countries and the option for Norwegian exiles to move from Britain to Sweden

After some discussion, it was decided that requests to land at Swedish airfields and those related to Norwegian exiles would be dropped. The LCS devised a plan to present the requests in stages rather than all at once. Various envoys would build relations with the Swedish government and present the proposals over a period of time.[2]

Operation

Agent Tate, 25 March 1944[3]

The first stage of Graffham began in March and April 1944. Sir Victor Mallet, the British Minister to Sweden, was recalled to London for a briefing on the operation. On 25 March, Wulf Schmidt, a double agent with the code name Tate, transmitted a message to his handlers explaining that Mallet was in the country to receive instructions and would be returning to Sweden for "important negotiations".[3][5][6]

Mallet traveled to Stockholm on 4 April where he met with Erik Boheman, the Swedish State Secretary for Foreign Affairs. During the meeting he presented the proposals for British reconnaissance flights and for the transport collaboration. The Swedish government rejected the former but accepted the latter. However, privately Boheman indicated that Sweden's air force would not pursue Allied planes in their airspace, and also that limitations of the transport collaboration meant it would have little benefit for the British.[5]

This was not an encouraging start for the operation but despite this, the LCS decided to continue with the deception. Colonel Thornton's trip was approved and he travelled to Stockholm toward the end of April. Thornton spent two weeks in Sweden, meeting with the head of the Royal Swedish Air Force, General Bengt Nordenskiöld.[5] The conferences were treated with a high degree of secrecy in the hope this would emphasise their importance. It had the required effect; Thornton's conversations were recorded by a pro-German chief of police and forwarded to Germany.[7] Despite siding with the Allies, Nordenskiöld communicated very little sensitive information to Thornton. Nordenskiöld was convinced that the Allies intended to invade Norway, but he kept this conviction to himself, contrary to Allied hopes. Thornton returned to England on 30 April.[5]

In tandem with these approaches, the British government began purchasing Norwegian securities.[5] The operation was replaced by Operation Royal Flush in June 1944, an expanded political deception also targeting Spain and Turkey.[8]

Impact

Overall the operation appeared to meet few of its initial aims. The political approach did lead to an increased discussion among the lower levels of Swedish officialdom as to the possibility of an invasion in Norway. However, it failed to convince the higher levels of government (with the exception of Nordenskiöld, who did not communicate his beliefs to anyone). Even the purchase of Norwegian securities went unnoticed. The overriding belief within the Swedish government was that any invasion of Norway would be diversionary, and that the European mainland would always be the main target of the Allies.[5]

Graffham was envisioned as a way to bolster the aims of Fortitude North, and overall this aspect of the plan was successful. German documents, captured after the war, showed that, although they did not believe Norway to be the main invasion target, the Fortitude North units were considered capable of a diversionary attack. As a result of the deceptions, German forces in Scandinavia were put on higher alert and were not transferred south to reinforce France.[6][9]

The extent to which both Graffham and Fortitude North influenced German strategy in Scandinavia is disputed, with some historians arguing that very little of either deception reached the enemy. While others argue that the existence of fictional units in Scotland helped confirm German fears of a diversionary attack in the region.[10]

References

- Latimer (2001), p. 218–232.

- Barbier (2007), p. 52.

- Levine (2011), p. 219.

- Howard (1990), p. 117.

- Barbier (2007), p. 53.

- Barbier (2007), p. 54.

- Crowdy (2008), p. 233.

- Crowdy (2008), p. 289.

- Barbier (2007), p. 60.

- Barbier (2007), p. 185.

Bibliography

- Barbier, Mary (2007). D-Day Deception: Operation Fortitude and the Normandy Invasion. Westport: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0-275-99479-1.

- Crowdy, Terry (2008). Deceiving Hitler: Double Cross and Deception in World War II. Oxford: Osprey. ISBN 1-84603-135-4.

- Howard, Michael (1990). British Intelligence in the Second World War: Strategic Deception (1. publ. ed.). Great Britain: HMSO. ISBN 0116309547.

- Latimer, Jon (2001). Deception in War. New York: New York: Overlook Press. ISBN 978-1-58567-381-0.

- Levine, Joshua (2011). Operation Fortitude: The True Story of the Key Spy Operation of WWII That Saved D-Day. London: HarperCollins UK. ISBN 0-00-741324-6.