Operation Ferdinand

Operation Ferdinand was a military deception employed by the Allies during the Second World War. It formed part of Operation Bodyguard, a major strategic deception intended to misdirect and confuse German high command about Allied invasion plans during 1944. Ferdinand consisted of strategic and tactical deceptions intended to draw attention away from the Operation Dragoon landing areas in southern France by threatening an invasion of Genoa in Italy. Planned by Eugene Sweeney in June and July 1944 and operated until early September, it has been described as "quite the most successful of 'A' Force's strategic deceptions".[1] It helped the Allies achieve complete tactical surprise in their landings and pinned down German troops in the Genoa region until late July.

| Operation Ferdinand | |

|---|---|

| Part of Operation Bodyguard | |

Ferdinand formed part of Operation Bodyguard, a Europe-wide deception strategy for 1944 | |

| Operational scope | Military deception |

| Planned | 1944 |

| Planned by | London Controlling Section |

| Objective | To draw attention away from planned Allied landings in Southern France |

Background

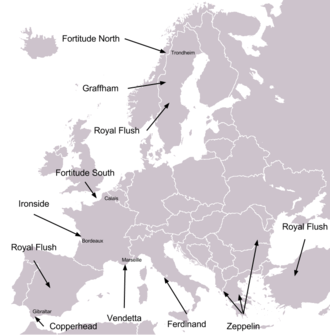

Operation Ferdinand formed part of Operation Bodyguard, a broad strategic military deception intended to confuse the Axis high command as to Allied intentions during the lead-up to the Normandy landings.[2] During early 1944 the main thrust of deceptions in the Middle Eastern theatre were contained under Operation Zeppelin (including its sub-plan Vendetta), which developed threats against Greece and Southern France, and Operation Royal Flush, which ran political deceptions against Spain and Turkey.[3] On 14 June the Allies committed to a landing in Southern France, codenamed Operation Dragoon (formerly Anvil).[4] Royal Flush and Zeppelin were scaled back, to tone down the threat to France, and it was decided a new plan (Ferdinand) was required to cover the intended invasion.[5][6]

The Allied nations invaded Italy in September 1943 and by mid-1944 had pushed the Germans back to the Gothic Line in the North of the country.[1][7] Ferdinand was intended to develop a threat against Genoa, as part of an expected Allied assault on the Gothic Line in August/September 1944.[4] German forces in the French Riviera (originally threatened by Vendetta) were to be put at relative ease, but not left feeling too secure lest they be moved to re-inforce Normandy.[8] Planning for the operation was handled by 'A' Force; the department in charge of deception in the Middle East.[9] A large part of the operation planning was handed to Major Eugene J Sweeney, an Irish-American career officer who had joined the department in late 1943 with the express task of learning the arts of deception before the war ended.[10] Working out of Algiers, at Advanced HQ (West), Sweeney helped implement several deceptions. The most notable of these was Operation Oakfield, the cover plan for Operation Shingle and the Battle of Anzio.[11][12]

John Bevan, head of the London Controlling Section, met with Colonel Dudley Clarke (head of 'A' Force) in Algiers in early June to decide on the outline for Ferdinand. After four days he returned to London leaving 'A' Force to work on the draft. On 4 July the draft was approved by Field Marshall Henry Wilson, Supreme Allied Commander in the Mediterranean theatre.[4][13] In July, Seventh Army HQ (the army due to be used for Dragoon) moved from Algeria to Naples. Sweeney moved with them, as the head of the newly formed No. 2 Tac HQ, and tasked by Colonel Clarke to focus entirely on planning for Ferdinand.[9][11] Sweeney worked on the plan until its final form on 28 July. Despite not being completed until the end of the month Ferdinand went into effect as soon as the first draft was approved.[4]

Operation

Ferdinand was a complex plan, involving misinformation and extensive physical deception. The underlying plot was the Allied forces had been surprised to find the Germans had not moved forces from the Mediterranean to re-inforce Normandy. Therefore, plans to invade southern France and the Balkans were looking less appealing. Instead the Allied commanders had decided to focus all of their resources on the Italian campaign. The real force assigned to Dragoon, the US VI Corps, would land in Genoa. Meanwhile, notional formations, such as the Seventh Army and the British 5th Airborne Division would support pushes along the Italian front and threaten targets in the Balkans. Ferdinand also recycled some of Zeppelin's threats against Turkey with the fictional British Ninth and Twelfth Armies.[4]

The key to Ferdinand was the threat to Genoa. Intelligence intercepts showed that the Abwehr (German military intelligence) listed it as one of the main areas they expected an Allied attack.[14] It was not possible to hide the buildup of naval and amphibious forces in the region, which were easily accessible to German aerial reconnaissance. German commanders identified both Genoa and southern France as the only logical targets, so the task for Allied double agents was to convince them that the former was the true goal.[15] The deception was maintained on the invasion date itself, with a tactical deception. The Dragoon fleet travelled on a course toward Genoa until late at night on 14 August, when they turned west toward their real target.[15]

The Ferdinand threat was continued until 8 September, to support the Allied efforts in France and Italy. It was 'A' Force's last major operation, a brief follow up called Braintree was designed but never implemented because the overall Bodyguard strategy had been mothballed in late August.[16]

Related operations

At the same time as Ferdinand, Tac HQ ran Otterington. This deception built a threat against Rimini in the east of Italy, in support of Alexander's proposed assault on the centre of the Gothic Line. It developed a pincer movement, in tandem with Ferdinand's threat to the west. However, once Otterington had gotten underway, with a major buildup of dummy armour, Alexander changed his plans and decided to push against Rimini. Clarke hastily implemented Ulster, a double bluff in which Otterington was revealed as a sham in the hope it would distract attention from that sector.[1]

Impact

Ferdinand successfully led Fremde Heere West (German military intelligence for the Western Front, also referred to as FHW) to expect a landing in Genoa. In late July and early August the buildup of forces in Italy made it clear that a seaborne invasion was imminent, and the deception was successful in creating this as a realistic threat to Genoa. As a result, the Dragoon landings achieved complete tactical surprise.[15] In his history of British wartime intelligence, historian Michael Howard calls it the "most successful of 'A' Force's strategic operations".[17] However, Howard states that the overwhelming force used for Operation Dragoon meant that the element of surprise was less important than on D-Day.[17]

References

- Holt (2005), p. 620.

- Latimer (2001), p. 218.

- Holt (2005), p. 597.

- Holt (2005), p. 616.

- Holt (2005), p. 602.

- Crowdy (2008), p. 290.

- Lloyd (2003), p. 93.

- Howard (1990), p. 155.

- Holt (2005), p. 615.

- Holt (2005), p. 592.

- Holt (2005), p. 609.

- Holt (2005), p. 830.

- Heathcote (1999), p. 310.

- Holt (2005), p. 617.

- Howard (1990), p. 158.

- Holt (2005), p. 622.

- Howard (1990), p. 159.

Bibliography

- Crowdy, Terry (2008). Deceiving Hitler: Double Cross and Deception in World War II. Oxford: Osprey. ISBN 978-1-84603-135-9.

- Heathcote, Tony (1999). The British Field Marshals 1736–1997. Barnsley (UK): Pen & Sword. ISBN 0-85052-696-5.

- Holt, Thaddeus (2005). The Deceivers: Allied Military Deception in the Second World War. New York: Phoenix. ISBN 0-7538-1917-1.

- Howard, Michael (1990). British Intelligence in the Second World War: Strategic Deception. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-40145-6.

- Latimer, Jon (2001). Deception in War. New York: Overlook Press. ISBN 978-1-58567-381-0.

- Lloyd, Mark (2003). The Art of Military Deception. New York: Pen and Sword. ISBN 1-4738-1196-1.