Ops (B)

Ops (B) was an Allied military deception planning department, based in the United Kingdom, during the Second World War. It was set up under Colonel Jervis-Read in April 1943 as a department of Chief of Staff to the Supreme Allied Commander (COSSAC), an operational planning department with a focus on western Europe. That year, Allied high command had decided that the main Allied thrust would be in southern Europe, and Ops (B) was tasked with tying down German forces on the west coast in general, and drawing out the Luftwaffe in particular.

The department's first operation was a three-pronged plan called Operation Cockade, an elaborate ploy to threaten invasions in France and Norway. Cockade was not much of a success. The main portion of the operation, a deceptive thrust against the Boulogne region named Operation Starkey, intended to draw out the German air arm, failed to elicit a response. The plan was undermined by the fact that any Allied push towards France that year was obviously unlikely.

In January 1944, COSSAC was absorbed into SHAEF and Ops (B) survived the transition, expanding in the process. Colonel Wild took over from Jervis-Read (who became his deputy) and reorganised the department into two sections: Operations and Intelligence. The refreshed department was given control over double agents and other avenues of disinformation. Ops (B) was tasked with operational planning for the main portion of Operation Bodyguard, a deception plan to cover the 1944 Normandy landings, named Operation Fortitude. In early 1944 David Strangeways joined the 21st Army (the invasion force); Strangeways clashed with Wild, and ended up rewriting major portions of Fortitude. Ops (B) was eventually relegated to the role of managing the information flowing out through disinformation channels.

Background

In March 1943, General Frederick E. Morgan was appointed Chief of Staff to the Supreme Allied Commander (Designate) (COSSAC), and tasked with operational planning in Northwest Europe.[1] Morgan's operational orders from Allied high command, received in April, referred to "an elaborate camouflage and deception" with the dual aim of keeping German forces in the west, and drawing the Luftwaffe into an air battle. The cross-channel invasion had already been postponed until 1944, and the main Allied push that year was toward southern Europe. Morgan's overall task was to help keep the enemy away from the fighting.[2][3]

In principle, overall deception strategy across all theatres of war fell to the London Controlling Section, a Whitehall department established in 1941 and by then run by Colonel John Bevan. Bevan convinced Morgan to establish a specialist deception section on his staff to conduct operational planning for the Western Front. However, Morgan's hierarchy was not set up to accommodate such a department. Instead, Ops (B) was set up within the "G-3" operations division in April 1943, and Colonel John Jervis-Read was appointed as its head.[2][4][lower-alpha 1] The concept was inspired by early successes in deception by Dudley Clarke and his 'A' Force in the Mediterranean theatre. However, Morgan disliked Clarke's department (referring to it as a "private army")[5] and Jervis-Read was given only limited resources.[5]

Bevan intended Ops (B) to focus on physical deception, with existing groups handling double agents, and so only one intelligence officer was assigned. Major Roger Fleetwoord-Hesketh was seconded from another part of COSSAC to act as intermediary between Ops (B) and the committee handing double agents.[6] The department was also assigned two Americans from the Ops (A) planning department, Lieutenant Colonel Percy Lash and Major Melvin Brown.[7]

Cockade

The department's first assignment was Operation Cockade, a deception intended to draw German attention from the Balkans by threatening invasions in France and Norway. Cockade was not a success. The operation was originally thought up by the London Controlling Section and, under the new departmental structure, Ops (B) was tasked with the operational planning.[4][5]

Cockade consisted of three operations throughout 1943, variously threatening invasions in Norway, Boulogne and Brest. The centrepiece was Operation Starkey, which included a major bombing campaign prior to a cross-channel amphibious "invasion". The feint failed to elicit any response from the enemy, who had already made up their mind that Allied action that year would be focused on the Mediterranean.[4][5]

One outcome of 1943 (and the failure of Cockade) was that control of operational deception in the Western theatre was fixed under the umbrella of Ops (B). Previously various groups had been involved in executing a deception strategy, with mixed results.[8]

Bodyguard

Following on from Cockade, Ops (B) was set to drafting the deception plans for Operation Overlord. In reality the task fell to the London Controlling Section, on account of lacking resources. However, in December 1943 Eisenhower was appointed Supreme Commander and in January 1944 it was decided a new, experienced, head was needed for Ops (B).[7][9] Noel Wild, Clarke's deputy at 'A' Force, was drafted in to replace Jervis-Head (who became Wild's deputy). Wild completely re-organised the department, dividing it into two branches: Operations and Intelligence. Jervis-Head became head of the Operations division whilst Lieutenant-Colonel Roger Fleetwood-Hesketh took charge of the Intelligence division.[7][10] Lash and Brown left Ops (B) Operations and returned to Ops (A), having only been temporary loan. An MI5 liaison, Major Christopher Harmer, joined Hesketh's intelligence section, as did a civilian secretary and Hesketh's brother Cuthbert.[7]

With these new resources Ops (B) was able to take over local planning for the Overlord deception plan, Operation Bodyguard. Wild began laying out strategy for Operation Fortitude, the portion of Bodyguard that would convince the Germans of a threat to both Norway and the Pas de Calais.[10] In January 1944, Ops (B) was granted membership of the Twenty Committee, the group that controlled all double agents in Britain and Western Europe.[11] From then on, material sent by double agents to their German handlers was created between Ops (B) and the individual agent's handlers.[12]

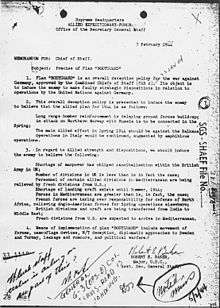

On 26 February, General Eisenhower issued the Fortitude Directive, which outlined who would be responsible for implementing the North and South portions of the Fortitude plan. GOC Scottish Command was tasked with Fortitude South, whilst the Joint Chiefs and 21st Army Group were given Fortitude South. For both plans, the Special Means were to be handled by SHAEF and Ops (B).[13] Field Marshal Montgomery, head of 21st Army Group, brought in David Strangeways (another 'A' Force alumni.) to command of R Force. He was tasked with implementing the Fortitude deception. Strangeways almost immediately objected to Ops (B)'s outline, and in fact rewrote Fortitude South to his liking.[7][14] Ops (B)'s Operations sub-section staff, for this period, were relegated to the role of courier between those groups implementing Fortitude North and South, to ensure the message of both plans were consistent with each other. By contrast, the department's Intelligence section were solely responsible for information disseminated via double agents, resulting in a constant stream of communication between SHAEF and R Force (Roger Fleetwood-Hesketh recounts how his brother made almost daily courier trips between London and Portsmouth).[13]

In May the Operations Section added four new members. Three Americans Lieutenant Colonel Frederic W. Barnes and Major Al Moody and Captain John B. Corbett and an Englishman. Sam Hood was another 'A' Force alumni who had been working for one of Clarke's tactical deception groups (TAC HQ) in Italy.[7]

Post-invasion

On 20 July, with R Force tied up running deception on the continent, control of Fortitude South was returned directly to Ops (B).[15] Wild decided to split Ops (B) into two groups. A forward section based in France, consisting of Jervis-Read and two others, was responsible for managing plans in the field. Wild kept the remainder of the team back in London to manage operations and planning in the UK.[16] In September, SHAEF moved its base to Versailles and Ops (B)'s American staff returned home. Wild moved the bulk of the team to Versailles, leaving Sam Hood in command in London.[16]

In June Ops (B) had begun work on Fortitude South II, it created a new American 2nd Army Group (SUSAG) to replace FUSAG and its threat to Calais. The story Ops (B) aimed to sell to the Germans was that the Allies, having met less resistance than planned, had moved FUSAG elements to France and intended to try and defeat Germany in Normandy. Strangeways, as before, objected to the plan on several grounds and once again rewrote it. In the end SUSAG was activated but never used (instead FUSAG continued to maintain the threat to Calais).[15]

Impact

Between January and February 1944, and from July onwards, Wild had significant authority over deception and misinformation on the Western Front. However, Ops (B)'s impact on the success of Bodyguard is debated. Wild himself was criticised as being "useless" whilst Strangeways deliberately frustrated Wild (for whom he had a personal dislike) at every turn.[17][18] Strangeways, along with others, identified key problems with the Bodyguard plan as outlined by Ops (B) and the LCS. He put significant pressure on SHAEF to have it re-written to his specification.[18]

See also

Notes

References

- Bond (2004)

- Holt (2004), pg. 477

- Hesketh (1999), pg. xv

- Latimer (2001), pg. 153

- Crowdy (2011), pg. 220

- Holt (2004), pg. 478

- Holt (2004), pg. 528–530

- Latimer (2001), pg. 155

- Hesketh (1999), pg. 28

- Crowdy (2011), pg. 230

- Hinsley (1990), pg. 237

- Hinsley (1990), pg. 238

- Hesketh (1999), pg. 29

- Holt (2004), pg. 536

- Holt (2004), pg. 584–585

- Holt (2004), pg. 634

- Holt (2004), pg. 530–531

- Holt (2004), pg. 532

Bibliography

- Bond, Brian (2004). "Morgan, Sir Frederick Edgworth (1894–1967)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/35103. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Crowdy, Terry (20 December 2011). Deceiving Hitler: Double Cross and Deception in World War II. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84603-135-9.

- Hesketh, Roger (1999). Fortitude: The D-Day Deception Campaign. St Ermin's Press. ISBN 0-316-85172-8.

- Hinsley, F.H.; Simkins, C.A.G. (1990). British intelligence in the Second World War : security and counter-intelligence. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521394090.

- Holt, Thaddeus (2004). The Deceivers: Allied Military Deception in the Second World War. Scribner. ISBN 0-7432-5042-7.

- Howard, Michael (1990). British Intelligence in the Second World War: Strategic Deception (1. publ. ed.). Great Britain: HMSO. ISBN 0-11-630954-7.

- Latimer, John (2001). Deception in War. New York: Overlook Press. ISBN 978-1-58567-381-0.

- Mure, David (1980). Master of Deception: Tangled Webs in London and the Middle East. W. Kimber. ISBN 0-7183-0257-5.