Madison, Georgia

Madison is a city in Morgan County, Georgia, United States. It is part of the Atlanta-Athens-Clarke-Sandy Springs Combined Statistical Area. The population was 3,979 at the 2010 census. The city is the county seat of Morgan County and the site of the Morgan County Courthouse.

Madison, Georgia | |

|---|---|

| City of Madison | |

Morgan County Courthouse at Madison | |

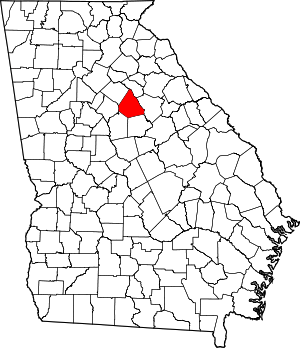

Location in Morgan County and the state of Georgia | |

Madison Location within the contiguous United States of America | |

| Coordinates: 33°35′17″N 83°28′21″W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | Morgan |

| Incorporated | December 12, 1809 |

| Named for | James Madison |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor–Council |

| • Mayor | Fred Perriman |

| • Council | Members

|

| Area | |

| • Total | 8.86 sq mi (22.94 km2) |

| • Land | 8.78 sq mi (22.75 km2) |

| • Water | 0.07 sq mi (0.19 km2) |

| Elevation | 679 ft (207 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 3,979 |

| • Estimate (2019)[3] | 4,210 |

| • Density | 479.28/sq mi (185.06/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| ZIP code(s) | 30650 |

| Area code(s) | 706 |

| FIPS code | 13-49196[4] |

| GNIS feature ID | 0332303[5] |

| Major airport | ATL |

| Website | madisonga |

The Historic District of Madison is one of the largest in the state.[6] Many of the nearly 100 antebellum homes have been carefully restored. Bonar Hall is one of the first of the grand-style Federal homes built in Madison during the town's cotton-boom heyday from 1840 to 1860.

Budget Travel magazine voted Madison as one of the world's 16 most picturesque villages.[7]

Madison is featured on Georgia's Antebellum Trail, and is designated as one of the state's Historic Heartland cities.

History

Early 19th century

Madison was described in an early 19th-century issue of White's Statistics of Georgia as "the most cultured and aristocratic town on the stagecoach route from Charleston to New Orleans."[6] In an 1849 edition of White's Statistics of Georgia, the following was written about Madison: "In point of intelligence, refinement, and hospitality, this town acknowledges no superior." On December 12, 1809, the town, named for 4th United States president, James Madison, was incorporated.[8]

While many believe that Sherman spared the town because it was too beautiful to burn during his March to the Sea, the truth is that Madison was home to pro-Union Congressman (later Senator) Joshua Hill. Hill had ties with General William Tecumseh Sherman's brother in the House of Representatives, so his sparing the town was more political than appreciation of its beauty.[9]

Jim Crow era

In 1895 Madison was reported to have an oil mill with a capital of $35,000, a soap factory, a fertilizer factory, four steam ginneries, a mammoth compress, two carriage factories, a furniture factory, a grist and flouringmill, a bottling works, a distillery with a capacity of 120 gallons a day, an ice factory with a capital of $10,500, a canning factory with a capital of $10,000, a bank with a capital of $75,000, surplus $12,000, and a number of small industries operated by individual enterprise.[10]

Against the backdrop of this Jim Crow-era prosperity, white Madisonians participated in at least three documented lynchings of African Americans. In February 1890, after a rushed trial involving knife-wielding jurors, Brown Washington, a 15-year-old,[11] was found guilty of the murder of a 9-year-old local white girl. After the verdict, though the sheriff with the governor's approval, called up the Madison Home Guard to protect Washington, "only three militiamen and none of the officers" [12] responded to the order. Washington was thus easily taken from jail by a posse of ten men organized by a "leading local businessman." [12] Described as "among the best citizens," they promptly handed him over to a mob of 300+ [11] waiting outside the courthouse. From there, he was taken to a telegraph pole behind a Mr. Poullain's residence,[11] allowed a prayer, then strung up and shot, his body mutilated by more than a hundred bullets. Afterwards, in the patriarchal exhibition-style common of southern lynchings, a sign was posted on the telegraph pole: "Our women and children will be protected." [12] His body was not taken down until noon the next day.[13]

According to Brundage's account of the lynching of Brown Washington in Lynching in the New South: Georgia and Virginia, 1880-1930:

The open participation of men 'of all ages and standing in life,' the carefully organized public meeting that planned the mob's course of action, the obvious complicity of the militia, and the ritualized execution of Washington all highlight the degree to which the lynching was sanctioned by the community at large. Shared attitudes toward women, sexuality, and black criminality, combined with local bonds of community and family, focused the fears and rage of whites on Washington and guaranteed mass involvement in his execution.[12]

In the aftermath, though local and state authorities vowed to thoroughly investigate the lynching as well as the Madison Home Guard's dereliction of duty,[13] just a week later a grand jury was advised by a judge of the superior court of Madison that any investigation would be a waste of time. In addition, the state body charged with investigating the home guard's non-response reported that their absence had been satisfactorily explained and no tribunal would be convened to investigate the matter.[14]"

Although the local Madisonian newspaper failed to report on the 1890 extra-judicial murder of Mr. Washington, an even earlier first lynching by Madisonians of a man they similarly pulled out of the old stone county jail appears in the contemporary accounts from the Atlanta Constitution.[14]

In 1919, ten years after the erection of a Lost Cause memorial in front of the newly built Morgan County courthouse, a third lynching occurred in the dark of night a few days before Thanksgiving. This time, citizens skipped the show-trials altogether, opting to travel to the home of Mr. Wallace Baynes in what one paper of the day called an "arresting party," though no charges against Mr. Baynes were stipulated in the news account.[15] Baynes shot at the party, striking Mr. Frank F. Ozburn of Madison in the head, killing him instantly. In response, the mob outside his home grew to 40-50 men. Despite the arrival of Madison Sheriff C.S. Baldwin, Mr. Baynes was pulled from his home by a rope and shot near the Little River. Afterwards, the sheriff present at the lynching said he could not identify any of the men who came for Mr. Baynes, despite the fact that they arrived in cars and lit up Mr. Baynes' home with the headlights of their vehicles.[15] In an editorial that argued that mobs in the south were no worse than mobs in the north yet condemned future lynchings, the local Madisonian claimed: "There is not now and perhaps will never be, any friction between the races here." [16]

The Lost Cause[17] monument erected in 1909 by the Morgan County Daughters of the Confederacy in front of the courthouse where Mr. Baynes was not afforded a trial was inscribed in part: "NO NATION ROSE/SO WHITE AND FAIR, NONE FELL SO PURE OF CRIME."[18] In the 1950s the monument was moved to Hill Park, a Madison city property donated by the descendants of Joshua Hill, the aforementioned pro-Union senator who before the civil war resigned his position rather than support secession.

Present day

Madison has one of the largest historic districts in the state of Georgia, and tourists from all over the world come to marvel at the antebellum architecture of the homes. Allie Carroll Hart was instrumental in establishing Madison's historical prestige.[19]

According to the Madison Historic Preservation Commission, "The Madison Historic District is listed in the National Register of Historic Places and is Madison's foremost tourist attraction. Preservation of the district and of each property within its boundary provides for the protection of Madison's unique historic character and quality environment. Madison's preservation efforts reflect a nationwide movement to preserve a "sense of place" amid generic modern development."

The Historic Preservation Commission consists of seven unelected/appointed members of the community. Before making exterior changes to their homes, property owners in the historic district must submit to a Historic Preservation Commission design review process, (meetings held once a month). If they receive a certificate of appropriateness they may then apply for a county building permit. Administrative HPC approval is required for roof replacement, fence installation (maximum heights apply), and some hardscape applications. Parking pads, demolitions, modern siding applications, and window replacements are rarely approved.[20]

Geography

Madison is located at 33°35′17″N 83°28′21″W (33.588038, -83.472368).[21] According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 8.9 square miles (23 km2), of which, 8.9 square miles (23 km2) of it is land and 0.04 square miles (0.10 km2) of it (0.45%) is water. Madison is situated on a high ridge which traverses Morgan County from the northeast to the southwest at an elevation of 760 feet.[10]

Interstate 20, U.S. Route 129, U.S. Route 441, and U.S. Route 278 pass through Madison. I-20 serves the city from exits 113 and 114, leading east 92 mi (148 km) to Augusta and west 59 mi (95 km) to Atlanta. U.S. 278 runs through the city from west to east, leading east 19 mi (31 km) to Greensboro and west 26 mi (42 km) to Covington. U.S. 129/441 run through the city from south to north together, leading north 29 mi (47 km) to Athens and south 22 mi (35 km) to Eatonton.

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1880 | 1,974 | — | |

| 1890 | 2,131 | 8.0% | |

| 1900 | 1,992 | −6.5% | |

| 1910 | 2,412 | 21.1% | |

| 1920 | 2,348 | −2.7% | |

| 1930 | 1,966 | −16.3% | |

| 1940 | 2,045 | 4.0% | |

| 1950 | 2,489 | 21.7% | |

| 1960 | 2,680 | 7.7% | |

| 1970 | 2,890 | 7.8% | |

| 1980 | 2,954 | 2.2% | |

| 1990 | 3,483 | 17.9% | |

| 2000 | 3,636 | 4.4% | |

| 2010 | 3,979 | 9.4% | |

| Est. 2019 | 4,210 | [3] | 5.8% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[22] | |||

As of the census[4] of 2000, there were 3,636 people, 1,362 households, and 964 families residing in the city. The population density was 410.2 people per square mile (158.5/km2). There were 1,494 housing units at an average density of 168.5 per square mile (65.1/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 48.93% White, 47.83% African-American, 0.08% Native American, 0.99% Asian, 1.10% from other races, and 1.07% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 2.09% of the population.

There were 1,362 households, out of which 32.0% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 44.0% were married couples living together, 22.6% had a female householder with no husband present, and 29.2% were non-families. 25.2% of all households were made up of individuals, and 10.7% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.61 and the average family size was 3.11.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 26.1% under the age of 18, 7.4% from 18 to 24, 28.2% from 25 to 44, 22.4% from 45 to 64, and 15.9% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 37 years. For every 100 females, there were 84.3 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 77.9 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $36,055, and the median income for a family was $40,265. Males had a median income of $40,430 versus $21,411 for females. The per capita income for the city was $19,551. About 10.3% of families and 11.6% of the population were below the poverty line, including 14.2% of those under age 18 and 13.3% of those age 65 or over.

Culture and parks

Madison is home to a handful of art galleries and museums. The Madison-Morgan Cultural Center (MMCC) provides a regional focus for performing and visual arts, plus permanent exhibits including a historical exhibit of Georgia's Piedmont region. The Center occupies an elegantly restored 1895 Romanesque Revival building and is located in the heart of Madison's nationally registered Historic District. Athens band, R.E.M., recorded an MTV Unplugged session at Madison-Morgan Cultural Center in 1991, where they played "Losing My Religion" with the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra.[23] Because of the legal dispute between Viacom and YouTube only a Japanese version of the permformance is available on YouTube. The song won the award for Best Pop Performance by a Duo or Group with Vocal at the 34th Annual Grammy Awards in 1992.

The Morgan County African American Museum is located in Madison.

Heritage Hall is maintained by the Morgan County Historical Society and has been restored for its architectural and historical significance. Heritage Hall was built in Greek Revival style in 1811 and was a private residence until 1977.

The Madison Artists' Guild has more than 150 members and is a nonprofit organization dedicated education and the encouragement of artistic endeavors in its members and the community through planned programs and regular gatherings.

Madison Museum of Fine Art, a charitable non-profit museum, is also located in the city.

There are four parks in the city limits. Wellington, Washington, and Hill Park are designated for active play, whereas Town Park is designed for events and public gatherings.[24]

Crime

According to a 2017 Crime Report produced by the city's Planning & Development Director, property crime rates in Madison are double and triple of nearby Social Circle and Watkinsville, Georgia, respectively. Violent crime remains steady at a rate of 10 violent crime incidents out of a population of 4,034, which makes its rates comparable with Social Circle and Watkinsville. In addition, property crime decreased in 2016 to a six-year low.[25] The online analytical platform Niche rates Madison's crime a "C" based on violent and property crime rates.[26]

Education

The Morgan County School District is a charter school system that covers pre-school to grade twelve, and consists of two elementary schools, a middle school, and a high school.[27] The district has 210 full-time teachers and over 3,171 students, with a high school completion rate of 71%.[28][29] The Superintendent is Dr. James Woodward whose background includes over 12 years serving the Georgia Department of Education in Agricultural and Career and Technical initiatives.[30]

- Morgan County Primary School

- Morgan County Elementary School 44% students proficient in math, 42% in reading.[31]

- Morgan County Middle School: 30% students proficient in math, 42% in reading.[32]

- Morgan County High School: 32% students proficient in math, 44% in reading.[33]

In popular culture

Parts of the 2017 film American Made starring Tom Cruise were shot in the Morgan County Courthouse.

Parts of the opening credits scene from the movie My Cousin Vinny, was filmed in Madison.

Significant parts of the movie Goosebumps (starring Jack Black) were filmed in Madison and at the Madison-Morgan Cultural Center.

In Harry Turtledove's final Southern Victory novel Volume 11: In at the Death, Madison was the site of an important climax to the long running series.

I'll Fly Away (1991–93), an NBC series starring Sam Waterston as a southern lawyer at the dawn of the civil rights movement, was shot largely in historic Madison.[34]

The historic mansion Bonar Hall was President Franklin D. Roosevelt's hospital in HBO's Warm Springs.

Road Trip was filmed in Madison

The 1978 movie The Great Bank Hoax starring Ned Beatty, Richard Basehart and Charlene Dallas was filmed in Madison.

Portions of the TV series, October Road were filmed in Madison.

Portions of the TV series, The Originals', were filmed in Madison. The show was a spin-off of The Vampire Diaries.

Hissy Fit, a novel by Mary Kay Andrews, is set in Madison.[35]

The main character of the webcomic, "Check, Please!" Eric "Bitty" Bittle is noted as being from Madison.

Notable people

- Benny Andrews, nationally recognized as an artist, teacher, author, activist, and advocate of the arts, grew up in rural Morgan County.

- Raymond Andrews (June 6, 1934 – November 25, 1991), African-American novelist, grew up in rural Morgan County.

- George Gordon Crawford (August 24, 1869 – March 20, 1936), industrialist, was born in Madison.

- Monday Floyd carpenter and Georgia Assemblyman who was harassed, threatened, and attacked by the Ku Klux Klan until he fled to Atlanta

- Oliver "Ollie" Hardy (born Norvell Hardy) (January 18, 1892 – August 7, 1957), comic actor famous as one half of Laurel and Hardy, lived in Madison as a child where his Mother owned a hotel called The Hardy House.[36] The Madison-Morgan Cultural Center is a preserved Romanesque Revival schoolhouse housing the room where Oliver Hardy attended first grade.

- Albert T. Harris, World War II naval hero was born in Madison.

- Allie Carroll Hart (1913–2003), director of the Georgia Department of Archives and History, 1964 to 1982.

- Bill Hartman (William Coleman "Bill" Hartman, Jr., March 17, 1915 – March 16, 2006) the Washington Redskins' running back, started playing American football in Madison.

- Jamond Simms (July-2015–Present) took Morgan County High School to four 3A GHSA State Championship games, winning 2 of 4 in 2016 and 2019.

- Joshua Hill (January 10, 1812 – March 6, 1891) was a United States Senator who lived in Madison. During the Civil War, General William Tecumseh Sherman, a friend of Hill, did not burn Madison, Georgia, on his "March to the Sea".

- Lancelot Johnston (1790–1866) resided in Madison. Johnston is credited with having perfected the process of extracting oil from cotton seed. He also invented the cotton seed huller.[37]

- Eugenius Aristides Nisbet began his practice of law in Madison Georgia, before later being elected as one of the three initial justices of the Supreme Court of Georgia in 1845.

- Brooks Pennington Jr., Georgia businessman, philanthropist and politician, operated his father's seed store on Main Street.

- Seaborn Reese (November 28, 1846 – March 1, 1907), the American politician, jurist and lawyer, was born in Madison. Reese filled the seat for Georgia in the United States House of Representatives during the 47th United States Congress. He was reelected to the 48th and 49th Congresses, serving from December 4, 1882, until March 3, 1887.

- Mark Schlabach, the American sports journalist, New York Times best-selling author and columnist and reporter for ESPN.com lives in Madison.

- William Tappan Thompson, humorist and writer who co-founded the Savannah Morning News newspaper in the 1850s, lived in Madison in the 1840s and worked on the city's first newspaper, The Southern Miscellany.[38]

- Jesse Triplett, lead guitarist with Collective Soul, was born in Madison[39] and attended the Morgan County School System.

- Philip Lee Williams (born January 30, 1950), novelist, poet, and essayist, grew up in Madison. He is the winner of many literary awards including the 2004 Michael Shaara Prize for his novel A Distant Flame (St. Martin's), an examination of southerners who were against the Confederacy's position in the American Civil War. He is also a winner of the Townsend Prize for Fiction for his novel The Heart of a Distant Forest, and has been named Georgia Author of the Year four times by the Georgia Writers Association. In 2007, he was recipient of a Georgia Governor's Award in the Humanities.

See also

References

- "Mayor & Council". Madison, GA. 2017. Retrieved May 16, 2017 – via CivicPlus .

- "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 9, 2020.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. October 25, 2007. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- "The Historical News". The Historical News. 21 (43): 7–8. June 2001.

- "World's 16 Most Picturesque Villages". Budget Travel. Retrieved March 18, 2018.

- "Madison". GeorgiaGov. n.d. Retrieved March 21, 2017.

- Melton, Brian (2002). "'The Town that Sherman Wouldn't Burn': Sherman's March and Madison, Georgia, in History, Memory, and Legend". Georgia Historical Quarterly. 86 (2): 201. Retrieved February 19, 2018.

- Cotton States Publishing and Advertising Company (1895). A Fruit Paradise. Issued for Madison and Morgan Counties, Georgia. Atlanta, Ga.: The Foote & Davies Co. LCCN tmp92003490. OL 22843961M – via Internet Archive.

- "Athens Weekly Banner". dlg.galileo.usg.edu. Retrieved May 17, 2018.

- Brundage, W. Fitzhugh (1993). Lynching in the New South: Georgia and Virginia, 1880-1930. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 9780252063459.

- "He Deserved His Fate: The Brave Men of Morgan Have Done Justice". The Atlanta Constitution. March 1, 1890.

- "There Will Be No Investigation: The Lynching of a Morgan County Negro Passes Out of Notice". The Atlanta Constitution. March 7, 1890.

- "Two Men Slain Near Broughton". The Madisonian. November 21, 1919.

- "Lynchings in Georgia". The Madisonian. December 1919.

- "An Appeal to the Women of Morgan County". The Madisonian. May 19, 1905.

- "Morgan County, Georgia Confederate Monument". waymarking.com.

- Henry, Derrick (July 26, 2003). "Carroll Hart, helped to save Georgia's past". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. p. E4.

- "Local Designation and Design Review Brochure".

- "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- "Watch "Losing My Religion" Live From MTV's 10th Anniversary Celebration | R.E.M.HQ". remhq.com. Retrieved March 18, 2018.

- "Madison City Parks".

- Callahan, Monica H. (October 9, 2017). "2017 Crime Report".

- "Madison, Georgia". May 16, 2018. Retrieved May 16, 2018.

- Georgia Board of Education, Retrieved June 24, 2010.

- School Stats, Retrieved June 24, 2010.

- "School Stats Morgan County High School Specific".

- "James Woodard's LinkedIn Profile".

- "Explore Morgan County Elementary School". Niche. Retrieved May 18, 2018.

- "Explore Morgan County Middle School". Niche. Retrieved May 18, 2018.

- "Explore Morgan County High School". Niche. Retrieved May 18, 2018.

- "Film Industry in Georgia | New Georgia Encyclopedia". georgiaencyclopedia.org. Retrieved March 18, 2018.

- Andrews, Mary Kay (March 5, 2015). Hissy Fit. Harper Paperbacks. ISBN 978-0060564650.

- Louvish, Simon (June 23, 2005). Stan and Ollie: The Roots of Comedy: The Double Life of Laurel and Hardy. Griffin: St. Martin's. pp. 40–41. ISBN 0312325983.

- Johnson, Lancelot. "Lancelot Johnson Paper" (PDF). ghs.galileo.usg.edu. Georgia Historical Society. Retrieved March 26, 2015.

- "Chapter 1 - Madison's History and Development". Madison, GA. Retrieved May 16, 2017 – via CivicPlus.

- Ruggieri, Melissa. "Atlanta Journal Constitution". Access Atlanata. Amy Glennon. Archived from the original on June 3, 2014. Retrieved May 26, 2014.

Further reading

- Strong, Robert Hale (1961). Halsey, Ashley (ed.). A Yankee Private's Civil War. Chicago: Henry Regnery Company. pp. 110–114. LCCN 61-10744. OCLC 1058411.

External links

- Government

- General information

- Community Settlement Historical Marker at The Historical Marker Database (HMdb.org)

- Madison Historical Marker at Digital Library of Georgia

- Madison – Morgan Chamber of Commerce at Madison Studios (madisonstudios.com)

- Madison – Morgan County Convention & Visitors Bureau at Madison Studios (madisonstudios.com)

- Morgan County Library at Azalea Regional Library System