Notoungulata

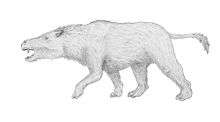

Notoungulata is an extinct order of mammalian ungulates that inhabited South America during the Paleocene to the Holocene, living from approximately 57 Ma to 11,000 years ago.[1][2] Notoungulates were morphologically diverse, with forms resembling animals as disparate as rabbits and rhinoceroses. Notoungula were the dominant group of ungulates in South America during the Paleogene and early Neogene. Their diversity declined during the Late Neogene, with only the large toxodontids persisting until the end of the Pleistocene. Several groups of Notoungulates separately evolved ever growing teeth like rodents and lagomorphs, a distinction among ungulates only shared with Elasmotherium.

| Notoungulata | |

|---|---|

| |

| Skeleton of Toxodon platensis | |

| |

| Skeleton of Propachyrucos (Hegetotheriidae) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| (unranked): | †Meridiungulata |

| Order: | †Notoungulata Roth 1903 |

| Suborders and Families | |

|

See text | |

Taxonomy

Notoungulata is divided into two major suborders, Typotheria and Toxodontia, alongside some basal groups (Notostylopidae and Henricosborniidae) which are potentially paraphyletic.[3] Due to the isolated nature of South America, many notoungulates evolved along convergent lines into forms that resembled mammals on other continents. Examples of this are Pachyrukhos, a notoungulate that filled an ecological niche similar to those of rabbits and hares, and Homalodotherium, which resembled chalicotheres. The families Interatheriidae, Hegetotheriidae, Mesotheriidae and Toxodontidae separately evolved high crowned (hypsodont) ever-growing teeth.[4] During the Pleistocene, Toxodon was the largest common notoungulate. Most of the group (Mixotoxodon, Piauhytherium and Toxodon being exceptions) became extinct after the landbridge between North and South America formed and allowed North American ungulates to enter South America in the Great American Interchange, and then to out-compete the native fauna.[5][6][7] Mixotoxodon was the only member of the group to be successful in invading Central America and southern North America, reaching as far north as Texas.[8]

This order is united with other South American ungulates in the super-order Meridiungulata. The notoungulate and litoptern native ungulates of South America have been shown by studies of collagen and mitochondrial DNA sequences to be a sister group to the perissodactyls, making them true ungulates.[9][10][11] The estimated divergence date is 66 million years ago.[11] This conflicts with the results of some morphological analyses which favoured them as afrotherians. It is in line with some more recent morphological analyses which suggested they were basal euungulates. Panperissodactyla has been proposed as the name of an unranked clade to include perissodactyls and their extinct South American ungulate relatives.[9]

Cifelli has argued that Notioprogonia is paraphyletic, as it would include the ancestors of the remaining suborders. Similarly, Cifelli indicated that Typotheria would be paraphyletic if it excluded Hegetotheria and he advocated inclusion of Archaeohyracidae and Hegetotheriidae in Typotheria.[12]

Notoungulata were for many years taken to include the order Arctostylopida, whose fossils are found mainly in China. Recent studies, however, have concluded that Arctostylopida are more properly classified as gliriforms, and that the notoungulates were therefore never found outside South and Central America.[13]

Based on an analysis of 133 morphological characters in 50 notoungulate genera, Billet in 2011 concluded that Homalodotheriidae, Leontiniidae, Toxodontidae, Interatheriidae, Mesotheriidae, and Hegetotheriidae are the only monophyletic families of notoungulates.[14]

Phylogeny

| Notoungulata |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Orders and families

- Order Notoungulata - notoungulates

- Suborder Notioprogonia

- Family Henricosborniidae

- Family Notostylopidae

- Suborder Toxodonta

- Family Isotemnidae

- Family Leontiniidae

- Family Notohippidae

- Family Toxodontidae

- Family Homalodotheriidae

- Suborder Typotheria

- Family Archaeopithecidae

- Family Oldfieldthomasiidae

- Family Interatheriidae

- Family Campanorcidae

- Family Mesotheriidae

- Suborder Hegetotheria

- Family Archaeohyracidae

- Family Hegetotheriidae

- Suborder Notioprogonia

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Notoungulata. |

- Notoungulata in the Paleobiology Database. Retrieved April 2013.

- Turvey, Samuel T. (2009-05-28). Holocene Extinctions. OUP Oxford. ISBN 9780191579981.

- Croft, Darin A.; Gelfo, Javier N.; López, Guillermo M. (2020-05-30). "Splendid Innovation: The Extinct South American Native Ungulates". Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences. 48 (1): 259–290. doi:10.1146/annurev-earth-072619-060126. ISSN 0084-6597.

- Gomes Rodrigues, Helder; Herrel, Anthony; Billet, Guillaume (2017-01-31). "Ontogenetic and life history trait changes associated with convergent ecological specializations in extinct ungulate mammals". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 114 (5): 1069–1074. doi:10.1073/pnas.1614029114. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 5293108. PMID 28096389.

- Webb, S. D. (1976). "Mammalian Faunal Dynamics of the Great American Interchange". Paleobiology. 2 (3): 220–234. doi:10.1017/S0094837300004802. JSTOR 2400220.

- Marshall, L. G.; Cifelli, R. L. (1990). "Analysis of changing diversity patterns in Cenozoic land mammal age faunas, South America". Palaeovertebrata. 19: 169–210. Retrieved 2018-10-08.

- Webb, S. D. (1991). "Ecogeography and the Great American Interchange". Paleobiology. 17 (3): 266–280. doi:10.1017/S0094837300010605. JSTOR 2400869.

- Lundelius, E. L.; Bryant, V. M.; Mandel, R.; Thies, K. J.; Thoms, A. (January 2013). "The first occurrence of a toxodont (Mammalia, Notoungulata) in the United States". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 33 (1): 229–232. doi:10.1080/02724634.2012.711405. hdl:1808/13587.

- Welker et al. 2015

- Buckley 2015

- Westbury et al. 2017

- Cifelli 1993

- Missiaen et al. 2006

- Billet 2011

Bibliography

- Billet, Guillaume (December 2011). "Phylogeny of the Notoungulata (Mammalia) based on cranial and dental characters". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 9 (4): 481–97. doi:10.1080/14772019.2010.528456. OCLC 740994816.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Buckley, M. (2015-04-01). "Ancient collagen reveals evolutionary history of the endemic South American 'ungulates'". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 282 (1806): 20142671. doi:10.1098/rspb.2014.2671. PMC 4426609. PMID 25833851.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cifelli, Richard L (1993). "The phylogeny of the native South American ungulates". In Szalay, F.S.; Novacek, M.J.; McKenna, M.C. (eds.). Mammal phylogeny: Placentals. 2. New York: Springer-Verlag. pp. 195–216. ISBN 0-387-97853-4. OCLC 715426850.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Missiaen, P; Smith, T; Guo, DY; Bloch, JI; Gingerich, PD (August 2006). "Asian gliriform origin for arctostylopid mammals". Naturwissenschaften. 93 (8): 407–11. doi:10.1007/s00114-006-0122-1. hdl:1854/LU-353125. PMID 16865388.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Roth, Santiago (1903). "Los Ungulados Sudamericanos". Anales del Museo de la Plata (Sección Paleontológica). 5: 1–36. OCLC 14012855.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Welker, F.; Collins, M. J.; Thomas, J. A.; Wadsley, M.; Brace, S.; Cappellini, E.; Turvey, S. T.; Reguero, M.; Gelfo, J. N.; Kramarz, A.; Burger, J.; Thomas-Oates, J.; Ashford, D. A.; Ashton, P. D.; Rowsell, K.; Porter, D. M.; Kessler, B.; Fischer, R.; Baessmann, C.; Kaspar, S.; Olsen, J. V.; Kiley, P.; Elliott, J. A.; Kelstrup, C. D.; Mullin, V.; Hofreiter, M.; Willerslev, E.; Hublin, J.-J.; Orlando, L.; Barnes, I.; MacPhee, R. D. E. (2015-03-18). "Ancient proteins resolve the evolutionary history of Darwin's South American ungulates". Nature. 522 (7554): 81–84. doi:10.1038/nature14249. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 25799987.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Westbury, M.; Baleka, S.; Barlow, A.; Hartmann, S.; Paijmans, J. L. A.; Kramarz, A.; Forasiepi, A. M.; Bond, M.; Gelfo, J. N.; Reguero, M. A.; López-Mendoza, P.; Taglioretti, M.; Scaglia, F.; Rinderknecht, A.; Jones, W.; Mena, F.; Billet, G.; de Muizon, C.; Aguilar, J. L.; MacPhee, R. D. E.; Hofreiter, M. (2017-06-27). "A mitogenomic timetree for Darwin's enigmatic South American mammal Macrauchenia patachonica". Nature Communications. 8: 15951. doi:10.1038/ncomms15951. PMC 5490259. PMID 28654082.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Carroll, Robert Lynn (1988). Vertebrate Paleontology and Evolution. New York: W.H. Freeman and Company. ISBN 9780716718222. OCLC 14967288.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McKenna, M.C. (1975). "Toward a phylogenetic classification of the Mammalia". In Luckett, W.P.; Szalay, F.S. (eds.). Phylogeny of the primates: a multidisciplinary approach (Proceedings of WennerGren Symposium no. 61, Burg Wartenstein, Austria, July 6–14, 1974). New York: Plenum. pp. 21–46. doi:10.1007/978-1-4684-2166-8_2. ISBN 978-1-4684-2168-2. OCLC 1693999.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McKenna, Malcolm C.; Bell, Susan K. (1997). Classification of Mammals Above the Species Level. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0231110138. OCLC 37345734.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)