Litopterna

Litopterna (from Ancient Greek: λῑτή πτέρνα "smooth heel") is an extinct order of fossil hoofed mammals from the Cenozoic era. The order is one of the five great clades of South American ungulates that gave the continent a unique fauna until the Great American Biotic Interchange. Like other endemic South American mammals, their relationship to other mammal groups has long been unclear.

| Litopterna | |

|---|---|

| |

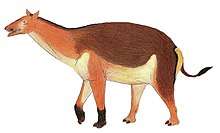

| Reconstruction of Macrauchenia | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| (unranked): | †Meridiungulata |

| Order: | †Litopterna Ameghino 1889 |

There were two major groups of litopterns: Prototheriidae and Macraucheniidae. Prototherids were medium to large animals that evolved adaptations for fast running, and occupied a variety of niches that elsewhere were filled by animals such as goats and antelopes, mouse deer, and horses. Macrauchenids were large to very large animals with long necks; they evolved retracted nasal openings, indicating that a number of their species likely had a muscular upper lip or short trunk. They likely filled roles in the environment similar to camels, giraffes, sivatheres, and browsing rhinoceroses on other continents. Many types of litopterns were abundant in South American faunas, all ate plants, and the group reached its maximum diversity in the late Miocene. All litoperns displayed toe reduction – three-toed forms developed, and some prototherids had a single hoof on each foot.[1]

Together with Neolicaphrium, Macrauchenia was among the youngest genera of litopterns, and these two appear to have been the only members of the group to survive the Great American Biotic Interchange. Both became extinct at the end of the Pleistocene. The genera that died out during this faunal exchange are presumed to have been driven to extinction at least in part by competition with invading North American ungulates.[2][3][4]

Evolutionary background

This order is known only from fossils in South America and Antarctica.[5][6] Litopterns, like the notoungulates and pyrotheres, are examples of ungulate mammals that evolved independently in "splendid isolation" on the island continent of South America. Like Australia, South America was isolated from all other continents following the breakup of Gondwana. During this period of isolation, unique mammals evolved to fill ecological niches similar to other mammals elsewhere. The Litopterna occupied ecological roles as browsers and grazers similar to perissodactyl and artiodactyl hoofed mammals in Laurasia.

Litopterns were common and varied in early faunas and persisted, in decreasing variety, into the Pleistocene. Early forms were originally classified by European and North American paleontologists as closely related to condylarths, believed to be the order that gave rise to modern hoofed mammals. Litopterns were seen as persisting condylarths, primitive mammals that survived in isolation. "Condylarth" is now recognized as a wastebasket taxon for any generalized early mammal that wasn't obviously a predator, making this theory outdated. The modern version of the idea is that litopterns are a sister group of one of the ungulate taxa whose early fossils are found in Eurasia, meaning that all hoofed mammals share distant common ancestors. However, an opposing view has been that litopterns (together with other South-American ungulates) originated independently from ungulates on other continents, and thus are unrelated to all the groups once called condylarths, including the early perissodactyls and artiodactyls. In the independent-origin theory, litopterns are classified with other endemic South American ungulates as the clade Meridiungulata.

Sequencing of mitochondrial DNA recently extracted from a Macrauchenia patachonica fossil from a cave in southern Chile indicates that Litopterna is the sister group to Perissodactyla, making litopterns true ungulates. The estimated divergence date is 66 million years ago.[7] Analyses of collagen sequences obtained from Macrauchenia and the notoungulate Toxodon have led to the same conclusion, and add notoungulates to the sister group clade to litopterns.[8][9] This idea contrasts with the results of some past morphological analyses which favoured them as afrotherians. It is consistent with some more recent morphological analyses which suggested they were basal euungulates. Panperissodactyla has been proposed as the name of an unranked clade to include perissodactyls and their extinct South American ungulate relatives.[8]

Families

- Order Litopterna

- Eolicaphrium

- Lambdaconus

- Paulogervaisia

- Proacrodon

- Proadiantus

- Family Protolipternidae - incertae sedis

- Asmithwoodwardia

- Miguelsoria

- Protolipterna

- Superfamily Macrauchenioidea

- Family Adianthidae

- Adianthinae

- Adianthus

- Proadiantus

- Proheptaconus

- Thadanius

- Tricoelodus

- Indaleciinae

- Adiantoides

- Indalecia

- Proheptoconus

- Adianthinae

- Family Macraucheniidae

- Family Mesorhinidae

- Coelosoma

- Mesorhinus

- Pseudocoelosoma

- Family Notonychopidae

- Notonychops

- Requisia

- Family Sparnotheriodontidae

- Notiolofos

- Notolophus

- Sparnotheriodon

- Family Adianthidae

- Superfamily Proterotherioidea

- Family Proterotheriidae

References

- Farina, Richard A, Sergio F. Vizcaino, and Gerry de Iuliis (2013). Megafauna; Giant Beasts of Pleistocene South America. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. pp. 174–75. ISBN 9780253002303.

- Webb, S. D. (1976). "Mammalian Faunal Dynamics of the Great American Interchange". Paleobiology. 2 (3): 220–234. doi:10.1017/S0094837300004802. JSTOR 2400220.

- Marshall, L. G.; Cifelli, R. L. (1990). "Analysis of changing diversity patterns in Cenozoic land mammal age faunas, South America". Palaeovertebrata. 19: 169–210. Retrieved 2018-10-08.

- Webb, S. D. (1991). "Ecogeography and the Great American Interchange". Paleobiology. 17 (3): 266–280. doi:10.1017/S0094837300010605. JSTOR 2400869.

- M. Bond; M. A. Reguero; S. F. Vizcaíno; S. A. Marenssi (2006). "A new 'South American ungulate' (Mammalia: Litopterna) from the Eocene of the Antarctic Peninsula". In J. E. Francis; D. Pirrie; J. A. Crame (eds.). Cretaceous-tertiary high-latitude palaeoenvironments: James Ross Basin, Antarctica. Geological Society, London, Special Publications. 258. The Geological Society of London. pp. 163–176. doi:10.1144/GSL.SP.2006.258.01.12.

- Gelfo, J. N.; Mörs, T.; Lorente, M.; López, G. M.; Reguero, M.; O'Regan, H. (2014-07-16). "The oldest mammals from Antarctica, early Eocene of the La Meseta Formation, Seymour Island". Palaeontology. 58 (1): 101–110. doi:10.1111/pala.12121.

- Westbury, M.; Baleka, S.; Barlow, A.; Hartmann, S.; Paijmans, J. L. A.; Kramarz, A.; Forasiepi, A. M.; Bond, M.; Gelfo, J. N.; Reguero, M. A.; López-Mendoza, P.; Taglioretti, M.; Scaglia, F.; Rinderknecht, A.; Jones, W.; Mena, F.; Billet, G.; de Muizon, C.; Aguilar, J. L.; MacPhee, R. D. E.; Hofreiter, M. (2017-06-27). "A mitogenomic timetree for Darwin's enigmatic South American mammal Macrauchenia patachonica". Nature Communications. 8: 15951. doi:10.1038/ncomms15951. PMC 5490259. PMID 28654082.

- Welker, F.; Collins, M. J.; Thomas, J. A.; Wadsley, M.; Brace, S.; Cappellini, E.; Turvey, S. T.; Reguero, M.; Gelfo, J. N.; Kramarz, A.; Burger, J.; Thomas-Oates, J.; Ashford, D. A.; Ashton, P. D.; Rowsell, K.; Porter, D. M.; Kessler, B.; Fischer, R.; Baessmann, C.; Kaspar, S.; Olsen, J. V.; Kiley, P.; Elliott, J. A.; Kelstrup, C. D.; Mullin, V.; Hofreiter, M.; Willerslev, E.; Hublin, J.-J.; Orlando, L.; Barnes, I.; MacPhee, R. D. E. (2015-03-18). "Ancient proteins resolve the evolutionary history of Darwin's South American ungulates". Nature. 522 (7554): 81–84. doi:10.1038/nature14249. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 25799987.

- Buckley, M. (2015-04-01). "Ancient collagen reveals evolutionary history of the endemic South American 'ungulates'". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 282 (1806): 20142671. doi:10.1098/rspb.2014.2671. PMC 4426609. PMID 25833851.

Further reading

- McKenna, Malcolm C; Bell, Susane K (1997). Classification of Mammals Above the Species Level. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-11013-6.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Litopterna. |

- An artist's rendition of a Macrauchenia, a representative genus of the Litopterna. Retrieved from the Red Académica Uruguaya megafauna page