Hoffstetterius

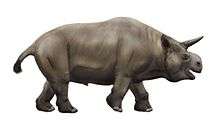

Hoffstetterius is an extinct genus of toxodontid notoungulate mammal, whose remains were discovered in the Middle to Late Miocene (Mayoan to Montehermosan) Mauri Formation in the La Paz Department in Bolivia.[1] The only described species is the type Hoffstetterius imperator.[2]

| Hoffstetterius | |

|---|---|

| |

| Skeletal drawing of the skull of the adult holotype of H. imperator | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Subfamily: | |

| Genus: | †Hoffstetterius Saint-André 1993 |

| Binomial name | |

| †Hoffstetterius imperator Saint-André 1993 | |

Etymology

The genus is named after paleontologist Robert Hoffstetter, who discovered the fossil in 1969.[2]

Discovery

The remains of Hoffstetterius were discovered in a volcanic tuff in the 6th member of the Mauri Formation, located in the northwestern part of the Bolivian highlands, to 5 kilometres (3.1 mi). near to the village of Achiri in the Pacajes Province, Bolivia. These volcanic sediments have been dated in 10.35 million years, which indicates that they are of the Late Miocene and would correspond to the Chasicoan mammal-age. The uncovered remains include the holotype specimen MNHN ACH1, a partial skull and mandible of an adult individual, plus postcranial remains including an axis, right humerus, both radius, part of the left ulna and left femur, retrieved by the expedition of the paleontologist Robert Hoffstetter in 1969.[2] A second specimen, the paratype MNHN BOL V 3291 corresponds to the partial skull of a juvenile individual, which comes from Cerro Pisakeri, also near to Achiri, recovered by the joint expedition of the French Institute of Andean Studies (IFEA) and The Geological Service of Bolivia (GEOBOL) in 1989. These remains were the basis for the designation of the new genus and species Hoffstetterius imperator in 1993 by French paleontologist Pierre-Antoine Saint-André. The name of the genus commemorates the scientific work of Professor Hoffstetter, while the name of the species, imperator ("emperor" in Latin) refers to the great sagittal crest of the animal, reminiscent of the crown of the emperors of the Holy Empire.[2]

Description

The skull of Hoffstetterius is high and elongated; in the holotype specimen it measures 527 millimetres (20.7 in) in length, while in the juvenile specimen it reaches 469 millimetres (18.5 in). The most notable characteristic of this is the elevation of the frontal bone over the nasals, forming a large sagittal crest, which is more developed in the adult individual, and also presents in the anterior frontal area a sort of triangular "shield", which may have served as a point of attachment for a keratinous horn, as in modern rhinoceroses and some toxodontids such as Trigodon and Paratrigodon. In dorsal view, the skull is triangular in shape. The mandible has a notorious projection pointing downwards into the mandibular ramus, at the level of the lower third molar (m3), a feature seen in other toxodontids such as Mixotoxodon and Pericotoxodon.[2]

The dental formula is 2.0.3.32.1.3.3 in the holotype; in the juvenile paratype it is 2.1.4.3[unknown]. Molar teeth have lingual folds with less depths than in other toxodontids such as Ocnerotherium, a well-developed middle lobe and a complex contour in the posterior lobe of the upper molar, apart from a sharp posterior edge in the upper third molar (M3), while in the second lower molar (m2) the lingual surface of the trigonid is much longer. The upper premolars lack of lingual folds and the upper molars lacking of the bifurcated lingual fold, a trait shared with advanced toxodontids such as Trigodon, Stereotoxodon and Mixotoxodon.[2]

The femur of Hoffstetterius has an elongated trochlear medial crest at its lower end, in the area of the knee joint, as in Toxodon. This type of structure may have served these toxodontids to maintain static their legs while standing, facilitating them to maintain this posture for long periods throughout the day without fatigue, as in modern horses and rhinoceroses.[3]

Classification

Hoffstetterius is clearly a toxodontid, identified by characteristics such as the hypsodont molars and the development of four large frontal hypselodont incisors of continuous growth. However, it is more difficult to establish its position within this family, since it has features in common with Ocnerotherium, which were considered as part of a subfamily called Dinotoxodontinae, while dental characteristics and the frontal prominence bring it closer to another subfamily, the Haplodontotheriinae; Saint-André considered it as part of the latter group in its initial description in 1992.[2] However, it seems that the traits that distinguish these subfamilies are actually found in different genera and therefore is better only distinguish between the primitive forms grouped in Nesodontinae and the more advanced Toxodontinae, including Hoffstetterius.[4]

Cladogram based in the analysis of Analía Forasiepi et al. (2014), showing the phylogenetic position of Hoffstetterius:[5]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Paleoenviroment

Hoffstetterius is one of the few toxodonts found in the Bolivian Altiplano, apart from another Late Miocene genus, Andinotoxodon, which has also been found in the Nabón Formation in Ecuador. The area is today at about 4,000 metres (13,000 ft) above sea level, but during the Late Miocene it was at an altitude of 1,600 to 1,200 metres (5,200 to 3,900 ft), with an average temperature of 20 °C (68 °F).[6] In this warmer environment were found plants typical from a subtropical dry forest, with plants of the genus Polylepis, Zyzyphus and Berberis,[6] whereas the contemporary fauna includes the mesotheriid Plesiotypotherium, a notoungulate that constitutes a fossil guide of the area;[7] the typothere Hemihegetotherium, remains of macrauchenids, rodents like dynomyids, octodontoids, caviods and the chinchillid Prolagostomus. Among the xenarthrans have been found remains of the glyptodontine Trachycalyptoides, the dasypodid Chorobates and the pampatherid Kraglievichia, along ground sloths like scelidotheriids, mylodontids, the nothrotherid Xyophorus and a megatherid.[8]

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hoffstetterius. |

- Hoffstetterius at Fossilworks.org

- Saint-Andre, P. A. (1993). Hoffstetterius imperator ng, n. sp. du Miocène supérieur de l'Altiplano bolivien et le statut des Dinotoxodontinés (Mammalia, Notoungulata). Comptes rendus de l'Académie des sciences. Série 2, Mécanique, Physique, Chimie, Sciences de l'univers, Sciences de la Terre, 316(4), 539-545.

- Shockey, B. J. (2001). Specialized knee joints in some extinct, endemic, South American herbivores. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica, 46(2).

- Bond, Mariano (2016). Ungulados nativos de Sudamérica. Una corta síntesis. En Historia evolutiva y paleobiogeográfica de los vertebrados de América del Sur. Contribuciones del MACN, Número 6. p. 296-301.

- Forasiepi, A. A. M.; Cerdeño, E.; Bond, M.; Schmidt, G. I.; Naipauer, M.; Straehl, F. R.; Martinelli, A. N. G.; Garrido, A. C.; Schmitz, M. D.; Crowley, J. L. (2014). "New toxodontid (Notoungulata) from the Early Miocene of Mendoza, Argentina". Paläontologische Zeitschrift. doi:10.1007/s12542-014-0233-5.

- Gregory-Wodzicki, K. M. (2002). A late Miocene subtropical-dry flora from the northern Altiplano, Bolivia. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 180(4), 331-348.

- Saint-Andre, P. A. (1994). Contribution à l'étude des grands mammifères du Néogène de l'Altiplano bolivien (Doctoral dissertation).

- Pujos, F., Antoine, P. O., Mamani Quispe, B., Abello, A., & Andrade Flores, R. (2012, September). The Miocene vertebrate faunas of Achiri, Bolivia. In Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology (Vol. 32, pp. 159-159).