Rhynchippus

Rhynchippus is an extinct genus of notoungulate mammals from the Late Oligocene (Deseadan in the SALMA classification) of South America. The genus was first described by Florentino Ameghino in 1897 and the type species is R. equinus, with lectotype MACN A 52–31.[2] Fossils of Rhynchippus have been found in the Sarmiento Formation of Argentina, the Salla and Petaca Formations of Bolivia, and in the Tremembé Formation of Brazil.[3]

| Rhynchippus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Rhynchippus equinus (on land) with Pyrotherium romeroi (in water) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | †Rhynchippus Ameghino 1897 |

| Type species | |

| Rhynchippus equinus Ameghino 1897 | |

| Species | |

| |

Description

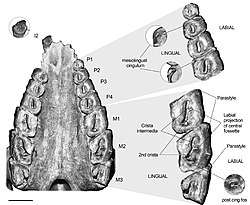

Rhynchippus was about 1 metre (3.3 ft) in length and weighted up to 120 kilograms (260 lb), with a deep body and three clawed toes on each foot.[4] Although its teeth were extremely similar to those of horses or rhinos, Rhynchippus was actually a relative of Toxodon, having developed teeth suitable for grazing through convergent evolution. Unlike its relatives, Rhynchippus had no large tusks; they were the same size and shape as the incisors. Enamel on the molars allowed it to chew tough food.[5] The genus shows similarities with Mendozahippus, Eurygenium and Pascualihippus.[1]

In 2016, a well-preserved specimen of R. equinus was described by Martínez et al. from the Sarmiento Formation in Patagonia.[6] The extraordinary preservation of the specimen allowed the researchers to appreciate the three connected spaces that constitute a heavily pneumatized middle ear; the epitympanic sinus, the tympanic cavity itself, and the ventral expansion of the tympanic cavity through the notably inflated bullae.[7]

Paleoecology

Fossils of Rhynchippus have been found in various fossiliferous stratigraphic units in South America, all restricted to the Deseadan South American land mammal age. Several specimens come from the Sarmiento Formation in the Golfo San Jorge Basin in southern Patagonia, with other finds from the Petaca Formation of the Subandean Belt in Bolivia, the Salla Formation from the same country, and the Tremembé Formation of the Taubaté Basin in eastern Brazil.

The Sarmiento and Salla Formations have provided a rich assemblage of many mammals and terror birds, as Physornis. The faunal assemblage of Rhynchippus fossil locations also constitutes several crocodylians, snakes (Madtsoia), helmeted bull frogs, a catfish; Taubateia paraiba, and the caiman Caiman tremembensis. The Tremembé Formation is known for the preservation of several insects.

Gallery

_(14577312258).jpg) Sketch of Rhynchippus by Frederic Brewster Loomis

Sketch of Rhynchippus by Frederic Brewster Loomis

Notes and references

Notes

- R. medianus is considered a junior synonym of R. equinus by Patterson[1]

References

- Martínez et al., 2016, p.5

- Martínez et al., 2016, p.6

- Rhynchippus at Fossilworks.org

- Patterson & Pires Costa, 2012, p.83

- Palmer et al., 1999, p.252

- Martínez et al., 2016, p.7

- Martínez et al., 2016, p.27

Bibliography

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Rhynchippus. |

- Martínez, Gastón; María Teresa Dozo; Javier N. Gelfo, and Hernán Marani. 2016. Cranial Morphology of the Late Oligocene Patagonian Notohippid Rhynchippus equinus Ameghino, 1897 (Mammalia, Notoungulata) with Emphases in Basicranial and Auditory Region. PLoS ONE 11. 1–29. Accessed 2019-03-02.

- Palmer, D. et al. 1999. The Marshall Illustrated Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs and Prehistoric Animals, 252. Marshall Editions. ISBN 1-84028-152-9

- Patterson, Bruce D., and Leonora Pires Costa. 2012. Bones, Clones, and Biomes: The History and Geography of Recent Neotropical Mammals, 1–432. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0226649191