Nor'easter

A nor'easter (also northeaster; see below) is a macro-scale extratropical cyclone in the western North Atlantic Ocean. The name derives from the direction of the winds that blow from the northeast. The original use of the term in North America is associated with storms that impact the upper north Atlantic coast of the United States and the Atlantic Provinces of Canada.

| Part of a series on |

| Weather |

|---|

|

|

|

Typically, such storms originate as a low-pressure area that forms within 100 miles (160 km) of the shore between North Carolina and Massachusetts. The precipitation pattern is similar to that of other extratropical storms. Nor'easters are usually accompanied by very heavy rain or snow, and can cause severe coastal flooding, coastal erosion, hurricane-force winds, or blizzard conditions. Nor'easters are usually most intense during winter in New England and Atlantic Canada. They thrive on converging air masses—the cold polar air mass and the warmer air over the water—and are more severe in winter when the difference in temperature between these air masses is greater.[1][2][3]

Nor'easters tend to develop most often and most powerfully between the months of November and March, although they can (much less commonly) develop during other parts of the year as well. The susceptible regions are generally impacted by nor'easters a few times each winter.[4][5][6]

Etymology and usage

The term nor'easter came to American English by way of British English. One of the earliest uses of this term is recorded in the Bible. In the book of Acts, the author Luke refers to a storm on the Mediterranean as a northeaster. The original Greek refers to this storm with the word Euroclydon, which is defined as "a storm with an east wind" or just "the east wind." [7][8][9] Other early recorded uses of the contraction nor (for north) in combinations such as nor'-east and nor-nor-west, as reported by the Oxford English Dictionary, date to the late 16th century, as in John Davis's 1594 The Seaman's Secrets: "Noreast by North raiseth a degree in sayling 24 leagues."[10] The spelling appears, for instance, on a compass card published in 1607. Thus, the manner of pronouncing from memory the 32 points of the compass, known in maritime training as "boxing the compass", is described by Ansted[11] with pronunciations "Nor'east (or west)," "Nor' Nor'-east (or west)," "Nor'east b' east (or west)," and so forth. According to the OED, the first recorded use of the term "nor'easter" occurs in 1836 in a translation of Aristophanes. The term "nor'easter" naturally developed from the historical spellings and pronunciations of the compass points and the direction of wind or sailing.

As noted in a January 2006 editorial by William Sisson, editor of Soundings magazine,[12] use of "nor'easter" to describe the storm system is common along the U.S. East Coast. Yet it has been asserted by linguist Mark Liberman (see below) that "nor'easter" as a contraction for "northeaster" has no basis in regional New England dialect; the Boston accent would elide the "R": no'theastuh'. He describes nor'easter as a "fake" word. However, this view neglects the little-known etymology and the historical maritime usage described above.

19th-century Downeast mariners pronounced the compass point "north northeast" as "no'nuth-east", and so on. For decades, Edgar Comee, of Brunswick, Maine, waged a determined battle against use of the term "nor'easter" by the press, which usage he considered "a pretentious and altogether lamentable affectation" and "the odious, even loathsome, practice of landlubbers who would be seen as salty as the sea itself". His efforts, which included mailing hundreds of postcards, were profiled, just before his death at the age of 88, in The New Yorker.[13]

Despite the efforts of Comee and others, use of the term continues by the press. According to Boston Globe writer Jan Freeman, "from 1975 to 1980, journalists used the nor’easter spelling only once in five mentions of such storms; in the past year (2003), more than 80 percent of northeasters were spelled nor'easter".[14]

University of Pennsylvania linguistics professor Mark Liberman has pointed out that while the Oxford English Dictionary cites examples dating back to 1837, these examples represent the contributions of a handful of non-New England poets and writers. Liberman posits that "nor'easter" may have originally been a literary affectation, akin to "e'en" for "even" and "th'only" for "the only", which is an indication in spelling that two syllables count for only one position in metered verse, with no implications for actual pronunciation.[15]

However, despite these assertions, the term can be found in the writings of New Englanders, and was frequently used by the press in the 19th century.

- The Hartford Times reported on a storm striking New York in December 1839, and observed, "We Yankees had a share of this same "noreaster," but it was quite moderate in comparison to the one of the 15h inst."[16]

- Thomas Bailey Aldrich, in his semi-autobiographical work The Story of a Bad Boy (1870), wrote "We had had several slight flurries of hail and snow before, but this was a regular nor'easter".[17]

- In her story "In the Gray Goth" (1869) Elizabeth Stuart Phelps Ward wrote "...and there was snow in the sky now, setting in for a regular nor'easter".[18]

- John H. Tice, in A new system of meteorology, designed for schools and private students (1878), wrote "During this battle, the dreaded, disagreeable and destructive Northeaster rages over the New England, the Middle States, and southward. No nor'easter ever occurs except when there is a high barometer headed off and driven down upon Nova Scotia and Lower Canada."[19]

Usage existed into the 20th century in the form of:

- Current event description, as the Publication Committee of the New York Charity Organization Society wrote in Charities and the commons: a weekly journal of philanthropy and social advance, Volume 19 (1908): "In spite of a heavy "nor'easter," the worst that has visited the New England coast in years, the hall was crowded."[20]

- Historical reference, as used by Mary Rogers Bangs in Old Cape Cod (1917): "In December of 1778, the Federal brig General Arnold, Magee master and twelve Barnstable men among the crew, drove ashore on the Plymouth flats during a furious nor'easter, the "Magee storm" that mariners, for years after, used as a date to reckon from."[21]

- A "common contraction for "northeaster"", as listed in Ralph E. Huschke's Glossary of Meteorology (1959).[22]

Geography and formation characteristics

Formation

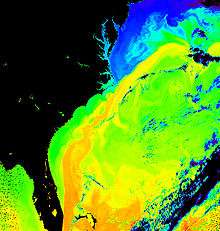

Nor'easters develop in response to the sharp contrast in the warm Gulf Stream ocean current coming up from the tropical Atlantic and the cold air masses coming down from Canada. When the very cold and dry air rushes southward and meets up with the warm Gulf stream current, which is often near 70 °F (21 °C) even in mid-winter, intense low pressure develops.

In the upper atmosphere, the strong winds of the jet stream remove and replace rising air from the Atlantic more rapidly than the Atlantic air is replaced at lower levels; this and the Coriolis force help develop a strong storm. The storm tracks northeast along the East Coast, normally from North Carolina to Long Island, then moves toward the area east of Cape Cod. Counterclockwise winds around the low-pressure system blow the moist air over land. The relatively warm, moist air meets cold air coming southward from Canada. The low increases the surrounding pressure difference, which causes the very different air masses to collide at a faster speed. When the difference in temperature of the air masses is larger, so is the storm's instability, turbulence, and thus severity.[1][23]

The nor'easters taking the East Coast track usually indicates the presence of a high-pressure area in the vicinity of Nova Scotia.[24] Sometimes a nor'easter will move slightly inland and bring rain to the cities on the coastal plain (New York City, Philadelphia, Baltimore, etc.) and snow in New England (Boston northward). On occasion, nor'easters can pull cold air as far south as Virginia or North Carolina, bringing as wet snow inland in those areas for a brief time.[25] Such a storm will rapidly intensify, tracking northward and following the topography of the East Coast, sometimes continuing to grow stronger during its entire existence. A nor'easter usually reaches its peak intensity while off the Canadian coast. The storm then reaches Arctic areas, and can reach intensities equal to that of a weak hurricane. It then meanders throughout the North Atlantic and can last for several weeks.[25]

Characteristics

Nor'easters are usually formed by an area of vorticity associated with an upper-level disturbance or from a kink in a frontal surface that causes a surface low-pressure area to develop. Such storms are very often formed from the merging of several weaker storms, a "parent storm", and a polar jet stream mixing with the tropical jet stream.

Until the nor'easter passes, thick, dark, low-level clouds often block out the sun. Temperatures usually fall significantly due to the presence of the cooler air from winds that typically come from a northeasterly direction. During a single storm, the precipitation can range from a torrential downpour to a fine mist. All precipitation types can occur in a nor'easter. High wind gusts, which can reach hurricane strength, are also associated with a nor'easter. On very rare occasions, such as in the nor'easter in 1978, North American blizzard of 2006, and January 2018 North American blizzard, the center of the storm can take on the circular shape more typical of a hurricane and have a small "dry slot" near the center, which can be mistaken for an eye, although it is not an eye.

Difference from tropical cyclones

Often, people mistake nor'easters for tropical cyclones and do not differentiate between the two weather systems. Nor'easters differ from tropical cyclones in that nor'easters are cold-core low-pressure systems, meaning that they thrive on drastic changes in temperature of Canadian air and warm Atlantic waters. Tropical cyclones are warm-core low-pressure systems, which means they thrive on purely warm temperatures.

Difference from other extratropical storms

A nor'easter is formed in a strong extratropical cyclone, usually experiencing bombogenesis. While this formation occurs in many places around the world, nor'easters are unique for their combination of northeast winds and moisture content of the swirling clouds. Nearly similar conditions sometimes occur during winter in the Pacific Northeast (northern Japan and northwards) with winds from NW-N. In Europe, similar weather systems with such severity are hardly possible; the moisture content of the clouds is usually not high enough to cause flooding or heavy snow, though NE winds can be strong.

Geography

The eastern United States, from North Carolina to Maine, and Eastern Canada can experience nor'easters, though most often they affect the areas from New England northward. The effects of a nor'easter sometimes bring high surf and strong winds as far south as coastal South Carolina. Nor'easters cause a significant amount of beach erosion in these areas, as well as flooding in the associated low-lying areas.

Biologists at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution on Cape Cod have determined nor'easters are an environmental factor for red tides on the Atlantic coast.

List of nor'easters

A list of nor'easters with short description about the events.

| Event | Date | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Great Blizzard of 1888 | March 11–14, 1888 | One of the worst blizzards in U.S. history. Dropped 40–50 inches (100–130 cm) of snow, killed 400 people, mostly in New York. |

| Great Appalachian Storm of November 1950 | November 24–30, 1950 | A very severe storm that dumped more than 30 inches (76 cm) of snow in many major metropolitan areas along the eastern United States, record breaking temperatures, and hurricane-force winds. The storm killed 353 people. |

| Ash Wednesday Storm of 1962 | March 5–9, 1962 | Caused severe tidal flooding and blizzard conditions from the Mid-Atlantic to New England, killed 40 people. |

| Eastern Canadian Blizzard of March 1971 | March 3–5, 1971 | Dropped over 32 inches (81 cm) of snow over areas of eastern Canada, killed at least 30 people. |

| Groundhog Day gale of 1976 | February 1–5, 1976 | Caused blizzard conditions for much of New England and eastern Canada, dropping a maximum of 56 inches (140 cm) of snow. |

| Northeastern United States blizzard of 1978 | February 5–7, 1978 | A catastrophic storm, which dropped over 27 inches (69 cm) of snow in areas of New England, killed a total of 100 people, mainly people trapped in their cars on metropolitan Boston's inner beltway and in Rhode Island. |

| 1991 Perfect Storm (the "Perfect Storm," combined Nor'easter/hurricane) | October 28 – November 2, 1991 | Very unusual storm in which a tropical and extratropical system interacted strangely, tidal surge caused severe damage to coastal areas, especially Massachusetts, killed 13 people. |

| December 1992 nor'easter | December 10–12, 1992 | A powerful storm which caused severe coastal flooding throughout much of the northeastern United States. |

| 1993 Storm of the Century | March 12–15, 1993 | A superstorm which affected the entire eastern U.S., parts of eastern Canada and Cuba. It caused 6.65 billion (2008 USD) in damage, and killed 310 people. |

| Christmas 1994 nor'easter | December 22–26, 1994 | An intense storm which affected the east coast of the U.S., and exhibited traits of a tropical cyclone. |

| North American blizzard of 1996 | January 6–10, 1996 | Severe snowstorm which brought up to 4 feet (120 cm) of snow to areas of the mid-atlantic and northeastern U.S.. |

| North American blizzard of 2003 | February 14–22, 2003 | Dropped over 2 feet (61 cm) of snow in several major cities, including Boston, and New York City, affected large areas of the Northeastern and Mid-Atlantic U.S., and killed a total of 27 people. |

| White Juan of 2004 | February 17–23, 2004 | A blizzard that affected Atlantic Canada, crippling transportation in Halifax, Nova Scotia, and dropping over 37 inches (94 cm) of snow in areas. |

| North American blizzard of 2005 | January 20–23, 2005 | Brought blizzard conditions to southern New England and dropped over 40 inches (100 cm) of snow in areas of Massachusetts. |

| North American blizzard of 2006 | February 11–13, 2006 | A powerful storm that developed a hurricane-like eye when off the coast of New Jersey. It brought over 30 inches (76 cm) of snow in some areas and killed 3 people. |

| April 2007 nor'easter | April 13–17, 2007 | An unusually late storm that dumped heavy snow in parts of Northern New England and Canada and heavy rains elsewhere. The storm caused a total of 18 fatalities. |

| November 2009 nor'easter | November 11–17, 2009 | Formed from the remnants of Hurricane Ida, produced moderate storm surge, strong winds and very heavy rainfall throughout the mid-atlantic region. It caused US$300 million (2009) in damage, and killed six people. |

| December 2009 North American blizzard | December 16–20, 2009 | A major blizzard which affected large metropolitan areas, including New York City, Philadelphia, Providence, and Boston. In some of these areas, the storm brought up to 2 feet (61 cm) of snow. |

| March 2010 nor'easter | March 12–16, 2010 | A slow-moving nor'easter that devastated the Northeastern United States. Winds of up to 70 miles per hour (110 km/h) snapped trees and power lines, resulting in over 1 million homes and businesses left without electricity. The storm produced over 10 inches (25 cm) of rain in New England, causing widespread flooding of urban and low-lying areas. The storm also caused extensive coastal flooding and beach erosion. |

| December 2010 North American blizzard | December 5, 2010 – January 15, 2011 | A severe and long-lasting blizzard which dropped up to 36 inches (91 cm) of snow throughout much of the eastern United States. |

| January 8–13, 2011 North American blizzard and January 25–27, 2011 North American blizzard | January 8–13 and January 25–27, 2011 | In January 2011, two nor'easters struck the East Coast of the United States just two weeks apart and severely crippled New England and the Mid-Atlantic. During the first of the two storms, a record of 40 inches (100 cm) was recorded in Savoy, Massachusetts. Two people were killed. |

| 2011 Halloween nor'easter | October 28 – November 1, 2011 | A rare, historic nor'easter, which produced record breaking snowfall for October in many areas of the Northeastern U.S., especially New England. The storm produced a maximum of 32 inches (81 cm) of snow in Peru, Massachusetts, and killed 39 people. After the storm, the rest of the winter for New England remained very quiet, with much less than average snowfall and no other significant storms to strike the region for the rest of the season. |

| November 2012 nor'easter | November 7–10, 2012 | A moderately strong nor'easter that struck the same regions that were impacted by Hurricane Sandy a week earlier. The storm exacerbated the problems left behind by Sandy, knocking down trees that were weakened by Sandy. It also left several residents in the Northeast without power again after their power was restored following Hurricane Sandy. Highest snowfall total from the storm was 13 inches (33 cm), recorded in Clintonville, Connecticut. |

| Late December 2012 North American storm complex | December 17–31, 2012 | A major nor'easter that was known for its tornado outbreak across the Gulf Coast states on Christmas day as well as giving areas such as northeastern Texas a white Christmas. The low underwent secondary cyclogenesis near the coast of North Carolina and dumped a swath of heavy snow across northern New England and New York, caused blizzard conditions across the Ohio Valley, as well as an ice storm in the mountains of the Virginia and West Virginia. |

| Early February 2013 North American blizzard | February 7–18, 2013 | An extremely powerful and historic nor'easter that dumped heavy snow and unleashed hurricane-force wind gusts across New England. Many areas received well over 2 feet (61 cm) of snow, especially Connecticut, Rhode Island, and eastern Massachusetts. The highest amount recorded was 40 inches (100 cm) in Hamden, Connecticut, and Gorham, Maine, received a record 35.5 inches (90 cm). Over 700,000 people were left without power and travel in the region came to a complete standstill. On the afternoon of February 9, when the storm was pulling away from the Northeastern United States, a well defined eye was seen in the center. The eye feature was no longer there the next day and the storm quickly moved out to sea. The nor'easter later moved on to impact the United Kingdom, before finally dissipating on February 20. The storm killed 18 people. |

| March 2013 nor'easter | March 1–21, 2013 | A large and powerful nor'easter that ended up stalling along the eastern seaboard due to a blocking ridge of high pressure in Newfoundland and pivoted back heavy snow and strong winds into the Northeast United States for a period of 2 to 3 days. Many officials and residents were caught off guard as local weather stations predicted only a few inches (several centimeters) of snow and a change over to mostly rain. Contrary to local forecasts, many areas received over one foot (30 cm) of snow, with the highest amount being 29 inches (74 cm) in Milton, Massachusetts. Several schools across the region, particularly in the Boston, Massachusetts, metropolitan area, remained in session during the height of the storm, not knowing the severity of the situation. Rough surf and rip currents were felt all the way southwards towards Florida's east coast. |

| January 2015 North American blizzard | January 23–31, 2015 | Unlike recent historical winter storms, there was no indication that a storm of this magnitude was coming until about 3 days in advance. The European computer model (ECMWF) first picked up on the potential for the nor'easter sometime before January 24. By the afternoon of January 24, most if not all major computer models were forecasting the storm to be much more severe than previously indicated earlier in the week. On the same day, the National Weather Service said they were aware about the potential for a major, crippling snowstorm but decided to hold off on winter weather headlines due to still being in the middle of another nor'easter. The Blizzard began as an Alberta Clipper in the Midwestern States, which was forecast to transfer its energy to a new, secondary Low Pressure off the coast of the Mid Atlantic and move northeastward and pass to the south and east of New England. Before the transition began, most of the area was being affected by generally light snow on the morning and afternoon of January 26. It wasn't until the evening into the early morning hours of January 27, that the storm was forecast to begin rapid deepening, stall, and also do a loop. It did stall for a time, however, the loop of the storm that was forecast did not happen. Due to this the storm began to slowly pull away to the northeast, a little quicker than expected. Contrary to local forecasts, western portions of the area, including western Connecticut and New York City only receiving a general 4 to 6 inches (10 to 15 cm) of snow, with a maximum of 9 inches (23 cm) recorded at Central Park. Further to the east, the storm brought over 20 inches (51 cm) of snow to much of the area, with several reports of over 30 inches (76 cm) across the State of Massachusetts, breaking many records. A maximum of 36 inches (91 cm) was recorded in at least four towns across Worcester County in Massachusetts and the city of Worcester itself received 34.5 inches (88 cm), marking the city's largest storm snowfall accumulation on record. The city of Boston recorded 24.6 inches (62 cm), making it the largest storm snowfall accumulation during the month of January and the city's sixth largest storm snowfall accumulation on record. On the coast of Massachusetts, Hurricane Force gusts up to around 80 mph (130 km/h) along with sustained winds between 50 and 55 mph (80 and 89 km/h) at times, were reported. The storm also caused severe coastal flooding and storm surge. The storm bottomed out to a central pressure of 970 mb (970 hPa). By January 28, the storm began to pull away from the area. |

| October 2015 North American storm complex | September 29 – October 2, 2015 | In early October, a low pressure system formed in the Atlantic, Tapping into moisture from Hurricane Joaquin, the storm dumped a huge amount of rain, mostly in South Carolina. |

| January 2016 United States blizzard (also known as Winter Storm Jonas, Snowzilla, or The Blizzard of 2016 by media outlets) | January 19–29, 2016 | This system dumped 2 to 3 feet (61 to 91 cm) of snow in the East Coast of the United States. States of Emergencies were declared in 12 States in advance of the storm as well as by the Mayor of Washington D.C.. The blizzard also caused significant storm surge in New Jersey and Delaware that was equal to or worse than Hurricane Sandy. Sustained damaging winds over 50 mph (80 km/h) were recorded in many coastal communities, with a maximum gust to 85 mph (137 km/h) on Assateague Island, Virginia. A total of 55 people died due to the storm. |

| February 2017 United States blizzard (also known as Winter Storm Niko and The Blizzard of 2017 by media outlets) | February 6–11, 2017 | Forming as an Alberta clipper in the northern United States on February 6, the system initially produced light snowfall from the Midwest to the Ohio Valley as it tracked southeastwards. It eventually reached the East Coast of the United States on February 9 and began to rapidly grow into a powerful nor'easter, dumping 1 to 2 feet (30 to 61 cm) across the Northeast Megapolis. The storm also produced prolific thunder and lightning across Southern New England. Prior to the blizzard, unprecedented and record-breaking warmth had enveloped the region, with record highs of above 60 °F (16 °C) recorded in several areas, including Central Park in New York City. Some were caught off guard by the warmth and had little time to prepare for the snowstorm. |

| October 2017 nor'easter | October 28–31, 2017 | An extratropical storm absorbed the remnants of Tropical Storm Philippe. The combined systems became an extremely powerful nor'easter that wreaked havoc across the Northeastern United States and Eastern Canada. The storm produced sustained tropical storm force winds along with hurricane-force wind gusts. The highest wind gust recorded was 93 mph (150 km/h) in Popponesset, Massachusetts. The storm caused over 1,400,000 power outages. Damage across New England, especially in Connecticut, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island, was extreme. This was due to the combination of the high winds, heavy rainfall, saturated ground, and most trees still being fully leaved. Autumn foliage in parts of northern New England was removed from the landscape in a matter of hours due to high winds. Some residents in Connecticut were without power for nearly a week following the storm. Heavy rain in Quebec and Eastern Ontario, with up to 98 mm (3.9 in) in the Canadian capital region of Ottawa, greatly interfered with transportation. |

| January 2018 North American blizzard | January 2–6, 2018 | A powerful blizzard that caused severe disruption along the East Coast of the United States and Canada. It dumped snow and ice in places that rarely receive wintry precipitation, even in the winter, such as Florida and Georgia, and produced snowfall accumulations of over 2 feet (61 cm) in the Mid-Atlantic states, New England, and Atlantic Canada. The storm originated on January 3 as an area of low pressure off the coast of the Southeast. Moving swiftly to the northeast, the storm explosively deepened while moving parallel to the Eastern Seaboard, causing significant snowfall accumulations. The storm received various unofficial names, such as Winter Storm Grayson, Blizzard of 2018 and Storm Brody. The storm was also dubbed a "historic bomb cyclone", with a minimum central pressure of 948 mb, similar to that of a Category 3 or 4 hurricane |

| March 1-3, 2018 nor'easter (also known as Winter Storm Riley or False Tropical Storm Riley by media outlets) | March 1–5, 2018 | A very powerful nor'easter that caused major impacts in the Northeastern, Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern United States. It originated as the northernmost low of a stationary front over the Midwest on March 1, which moved eastward into the Northeast later that night. A new low pressure system rapidly formed off the coast on March 2 as it slowly meandered near the coastline. It peaked later that day and began to gradually move out to sea by March 3. Producing over 2 feet (24 in) of snow in some areas, it was one of the most significant March snowstorms in many areas, particularly in Upstate New York. In other areas, it challenged storm surge records set by other significant storms, such as Hurricane Sandy. It also produced widespread damaging winds, with gusts well over Hurricane force strength in some areas across Eastern New England as well as on the back side in the Mid-Atlantic via a sting jet. Over 2.2 million customers were left without power. |

| March 6-8, 2018 nor'easter (also known as Winter Storm Quinn by media outlets) | March 2–9, 2018 | A powerful nor'easter that affected the Northeast United States. It came just days after another nor'easter devastated much of the Northeast. Frequent cloud to ground Thundersnow as well as snowfall rates of up to 3 inches (7.6 cm) an hour were reported in areas around the Tri-State Area, signaling the rapid intensification of the storm. Late in the afternoon, an eye-like feature was spotted near the center of the storm. It dumped over 2 feet of snow in many areas across the Northeast, including many areas in New England where the predominant precipitation type was rain for the previous storm. Over 1 million power outages were reported at the height of the storm due to the weight of the heavy, wet snow on trees and power lines. Many people who lost power in the previous storm found themselves in the dark again. |

| March 12–14, 2018 nor'easter (also known as Winter Storm Skylar by media outlets) | March 11–14, 2018 | A powerful nor'easter that affected portions of the Northeast United States. The storm underwent rapid intensification with a central millibaric pressure dropping down from 1001 mb to 974 mb in just 24 hours. This was the third major storm to strike the area within a period of 11 days. The storm dumped over up 2 feet of snow and brought Hurricane-force wind gusts to portions of Eastern New England. Hundreds of public school districts including, Boston, Hartford, and Providence were closed on Tuesday, March 13. |

| March 20–22, 2018 nor'easter (also known as Winter Storm Toby and Four'Easter by media outlets) | March 20–22, 2018 | A powerful nor'easter that became the fourth major nor'easter to affect the Northeast United States in a period of less than three weeks. It caused a severe weather outbreak over the Southern United States on March 19 before moving off of the North Carolina coast on March 20 and spreading freezing rain and snow into the Mid-Atlantic States after shortly dissipating later that night. A new low pressure center then formed off of Chesapeake Bay on March 21 and then became the primary nor'easter. Dry air prevented most of the precipitation from reaching the ground in areas in New England such as Boston, Hartford, and Providence, all of which received little to no accumulation, in contrast with what local forecasts had originally predicted. In Islip, New York at the height of the storm, snowfall rates of up to 5 inches per hour were reported. 8 inches was reported at Central Park and over 12 inches was reported in many locations on Long Island as well in and around New York City and in parts of New Jersey. Over 100,000 customers lost power at the peak of the storm, mostly due to the weight of the heavy, wet snow on trees and power lines, with a majority of the outages being in New Jersey. |

| July 21–22, 2018 nor'easter | July 21–22, 2018 | A rare summertime nor'easter that developed off the coast of North Carolina along the warm front of a powerful upper level low during July 21 and retrograded to the west into Delaware and Pennsylvania then rapidly weakened in Upstate New York on the morning of July 22. An extremely rare summertime Wind Advisory was issued for parts of New Jersey, New York City, Long Island, and Connecticut. The storm produced strong to damaging winds that created tropical storm conditions for much of New Jersey, New York City, and Long Island. The western side of the storm also brought excessive rainfall and extensive flooding in several metropolitan areas in the Mid-Atlantic States while the tail of the storm channeled a huge moisture feed into Southern New England along with the threat for waterspouts and tornadoes, though none were reported. |

| October 25–28 nor'easter | October 25–28, 2018 | An early season nor'easter that developed along the Gulf Coast near Louisiana and trekked northeastward then northward into Long Island and Southern New England. It formed on October 25 and absorbed the remnant moisture from Hurricane Willa. It brought severe weather along the Gulf Coast, Florida, and the Carolinas, though only minor instances were reported. The nor'easter intensified on October 26 and the morning of October 27th, before becoming occluded and moving inland late on the 27th. The storm brought strong to damaging winds for many coastal areas in the Northeast as well as moderate to major coastal flooding for New York City, Long Island, and parts of Connecticut, with levels coming close to what was experienced during Hurricane Sandy, especially in western parts of Long Island Sound. The storm was also responsible for an early season snow to parts of Upstate New York and Northern New England. Accumulations were minor. |

| April 2–4 nor'easter | April 2–4, 2019 | A very significant, large, and intense late season Nor'easter that brushed parts of the East Coast of the United States while undergoing explosive cyclogensis. Impacts were thankfully very minor and limited to light to moderate rain in parts of Eastern North Carolina and in Rhode Island and Southeastern Massachusetts. Some snow, however was reported in downtown Charlotte and nearby locations in North Carolina during the afternoon of April 2, though no accumulation was reported. Minor accumulations were reported in parts of Downeast Maine as well as in the higher terrain areas of Northern Massachusetts and Connecticut before daybreak on April 3. Behind the storm, many of these same areas that experienced snow warmed significantly in a matter of a few hours from around 30 degrees to above 60 degrees on strong westerly winds of 50 mph. The winds prompted several Red Flag Warnings across the Northeastern United States, mainly west of the Hudson River Valley. On April 4, while the winds were weaker, Red Flag Warnings were then expanded to all of Southern New England and Long Island. Winds of 50 mph continued across Eastern Maine as the nor'easter continued to pull into the Canadian Maritimes. |

| March 5–8 nor'easter | March 5–8, 2020 | An extremely significant and powerful Nor'easter that nearly missed the Northeastern United States. It underwent bombogensis and developed into a Hurricane Force Low Pressure as it passed well south and east of the 40 North/70 West Benchmark. The same storm was responsible for a Tornado Outbreak in the Southeastern United States days prior. Impacts along the East Coast were limited to light rain and snow showers for most with High Wind Warning conditions and minor snow accumulations and near Blizzard conditions for Cape Cod and the Islands. A buoy to the southeast of Nantucket reported Sustained Winds of 55 mph and Gusts up to 74 mph before going offline. An eye-like feature was seen on radar on the morning of March 7 as the storm pulled away. |

| March 31 – April 4 nor'easter | March 31 – April 4, 2020 | A very significant, large, and intense late season Nor'easter that narrowly missed the East Coast of the United States while undergoing bombogensis into a Hurricane Force Low with a very large wind field. It stalled and looped over the open Atlantic due to the Greenland Block and came close enough to parts of Southern New England to bring rain and snow as well as gusty to damaging winds while looping, especially in Eastern Massachusetts. Similar to Tropical Cyclones, the Nor'easter exhibited an eye-like feature while at its peak intensity, which was less than 980 millibars at one point. |

| April 12-13 nor'easter | April 12-13, 2020 | A very large and significant extratropical cyclone developed from moisture from the Gulf of Mexico on April 10. A series of destructive tornadoes affected the Southeastern United States on Easter Sunday and Monday, April 12–13, 2020. Several were responsible for prompting tornado emergencies, including the first one to be issued by the National Weather Service in Charleston, South Carolina. A large squall line formed and tracked through the mid-Atlantic on April 13, prompting multiple tornado warnings and watches. Fifteen total watches were produced during the course of the event, two of which were designated Particularly Dangerous Situations. With 34 tornadic fatalities reported, it was the deadliest tornado outbreak in the U.S. since the April 2014 tornado outbreak. The nor'easter moved up the east coast, affecting areas such as New York, New Jersey, Delaware, Maryland, Washington D.C., Virginia, and North Carolina with 70 mph winds. A wind gust of 82 mph was reported in New Jersey. |

See also

References

- Multi-Community Environmental Storm Observatory (2006). "Nor'easters". Multi-community Environmental Storm Observatory. Archived from the original on October 9, 2007.

- "Know the dangers of nor'easters". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on February 14, 2016.

- How stuff works (2006). "What are nor'easters?". Retrieved January 22, 2008.

- "National Weather Service". National Weather Service. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved February 29, 2016.

- "AccuWeather.com".

- L. Dove, Laurie. "What's a nor'easter?".

- Acts 27:14

- https://levendwater.org/bible_interlinear/greek/2148.htm

- https://www.scripture4all.org/OnlineInterlinear/NTpdf/act27.pdf

- "nor'-east, n., adj., and adv." OED Online. Oxford University Press, January 2018. Web. March 13, 2018.

- Ansted. A Dictionary of Sea Terms, Brown Son & Ferguson, Glasgow, 1933

- "Featuring Boating News, Stories and More". Soundings Online. Retrieved August 18, 2012.

- McGrath, Ben (September 5, 2005). "Nor'Easter". The New Yorker: Tsk-Tsk Dept. Condé Nast. Retrieved June 3, 2013.

- Freeman, Jan (December 21, 2003). "Guys and dolls". Boston Globe: The Word. The New York Times Company. Retrieved June 3, 2013.

- Liberman, Mark (January 25, 2004). "Nor'Easter Considered Fake". Language Log. Retrieved June 3, 2013.

- "Snow Storm", The Hartford Times, Hartford, December 28, 1836

- Thomas Bailey Aldrich (1911). The Story of a Bad Boy. Houghton, Mifflin. Retrieved May 19, 2013.

- Charles Dudley Warner (1896). Library of the World's Best Literature. Retrieved October 10, 2013.

- John H. Tice (1878). A new system of meteorology, designed for schools and private students: Descriptive and explanatory of all the facts, and demonstrative of all the causes and laws of atmospheric phenomena. Tice & Lillingston. Retrieved May 19, 2013.

- Charities and the Commons: A Weekly Journal of Philanthropy and Social Advance. Publication Committee of the New York Charity Organization Society. 1908. p. unknown. Retrieved May 19, 2013.

- Mary Rogers Bangs (1920). Old Cape Cod: The Land, the Men, the Sea. Houghton Mifflin. pp. 182–. Retrieved May 19, 2013.

- Ralph E. Huschke (1959). Glossary of Meteorology. American Meteorological Soc. Retrieved May 19, 2013.

- Storm-E (2007). "Nor'easters". Archived from the original on June 26, 2007. Retrieved January 22, 2008.

- The Weather Channel (2007). "Nor'easters". The Weather Channel. Archived from the original on April 8, 2016. Retrieved January 24, 2016.

- Multi-Community Environmental Storm Observatory (2006). "Nor'easters". Archived from the original on October 9, 2007. Retrieved January 22, 2008.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Nor'easters. |

- Blizzard Video: Dec 9, 2005 (duration: 9m59sec)

- Archived issues of NOR'EASTER (Magazine of the Northeast Sea Grant Programs), published until 1999.

- Duxbury, Massachusetts April 2007 Nor'easter photos