Theory of relativity

The theory of relativity usually encompasses two interrelated theories by Albert Einstein: special relativity and general relativity.[1] Special relativity applies to all physical phenomena in the absence of gravity. General relativity explains the law of gravitation and its relation to other forces of nature.[2] It applies to the cosmological and astrophysical realm, including astronomy.[3]

| Part of a series of articles about | ||||||

| General relativity | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

|

Fundamental concepts |

||||||

|

Phenomena |

||||||

|

||||||

The theory transformed theoretical physics and astronomy during the 20th century, superseding a 200-year-old theory of mechanics created primarily by Isaac Newton.[3][4][5] It introduced concepts including spacetime as a unified entity of space and time, relativity of simultaneity, kinematic and gravitational time dilation, and length contraction. In the field of physics, relativity improved the science of elementary particles and their fundamental interactions, along with ushering in the nuclear age. With relativity, cosmology and astrophysics predicted extraordinary astronomical phenomena such as neutron stars, black holes, and gravitational waves.[3][4][5]

Development and acceptance

Albert Einstein published the theory of special relativity in 1905, building on many theoretical results and empirical findings obtained by Albert A. Michelson, Hendrik Lorentz, Henri Poincaré and others. Max Planck, Hermann Minkowski and others did subsequent work.

Einstein developed general relativity between 1907 and 1915, with contributions by many others after 1915. The final form of general relativity was published in 1916.[3]

The term "theory of relativity" was based on the expression "relative theory" (German: Relativtheorie) used in 1906 by Planck, who emphasized how the theory uses the principle of relativity. In the discussion section of the same paper, Alfred Bucherer used for the first time the expression "theory of relativity" (German: Relativitätstheorie).[6][7]

By the 1920s, the physics community understood and accepted special relativity.[8] It rapidly became a significant and necessary tool for theorists and experimentalists in the new fields of atomic physics, nuclear physics, and quantum mechanics.

By comparison, general relativity did not appear to be as useful, beyond making minor corrections to predictions of Newtonian gravitation theory.[3] It seemed to offer little potential for experimental test, as most of its assertions were on an astronomical scale. Its mathematics seemed difficult and fully understandable only by a small number of people. Around 1960, general relativity became central to physics and astronomy. New mathematical techniques to apply to general relativity streamlined calculations and made its concepts more easily visualized. As astronomical phenomena were discovered, such as quasars (1963), the 3-kelvin microwave background radiation (1965), pulsars (1967), and the first black hole candidates (1981),[3] the theory explained their attributes, and measurement of them further confirmed the theory.

Special relativity

Special relativity is a theory of the structure of spacetime. It was introduced in Einstein's 1905 paper "On the Electrodynamics of Moving Bodies" (for the contributions of many other physicists see History of special relativity). Special relativity is based on two postulates which are contradictory in classical mechanics:

- The laws of physics are the same for all observers in any inertial frame of reference relative to one another (principle of relativity).

- The speed of light in a vacuum is the same for all observers, regardless of their relative motion or of the motion of the light source.

The resultant theory copes with experiment better than classical mechanics. For instance, postulate 2 explains the results of the Michelson–Morley experiment. Moreover, the theory has many surprising and counterintuitive consequences. Some of these are:

- Relativity of simultaneity: Two events, simultaneous for one observer, may not be simultaneous for another observer if the observers are in relative motion.

- Time dilation: Moving clocks are measured to tick more slowly than an observer's "stationary" clock.

- Length contraction: Objects are measured to be shortened in the direction that they are moving with respect to the observer.

- Maximum speed is finite: No physical object, message or field line can travel faster than the speed of light in a vacuum.

- The effect of Gravity can only travel through space at the speed of light, not faster or instantaneously.

- Mass–energy equivalence: E = mc2, energy and mass are equivalent and transmutable.

- Relativistic mass, idea used by some researchers.[9]

The defining feature of special relativity is the replacement of the Galilean transformations of classical mechanics by the Lorentz transformations. (See Maxwell's equations of electromagnetism).

General relativity

General relativity is a theory of gravitation developed by Einstein in the years 1907–1915. The development of general relativity began with the equivalence principle, under which the states of accelerated motion and being at rest in a gravitational field (for example, when standing on the surface of the Earth) are physically identical. The upshot of this is that free fall is inertial motion: an object in free fall is falling because that is how objects move when there is no force being exerted on them, instead of this being due to the force of gravity as is the case in classical mechanics. This is incompatible with classical mechanics and special relativity because in those theories inertially moving objects cannot accelerate with respect to each other, but objects in free fall do so. To resolve this difficulty Einstein first proposed that spacetime is curved. In 1915, he devised the Einstein field equations which relate the curvature of spacetime with the mass, energy, and any momentum within it.

Some of the consequences of general relativity are:

- Gravitational time dilation: Clocks run slower in deeper gravitational wells.[10]

- Precession: Orbits precess in a way unexpected in Newton's theory of gravity. (This has been observed in the orbit of Mercury and in binary pulsars).

- Light deflection: Rays of light bend in the presence of a gravitational field.

- Frame-dragging: Rotating masses "drag along" the spacetime around them.

- Metric expansion of space: the universe is expanding, and the far parts of it are moving away from us faster than the speed of light.

Technically, general relativity is a theory of gravitation whose defining feature is its use of the Einstein field equations. The solutions of the field equations are metric tensors which define the topology of the spacetime and how objects move inertially.

Experimental evidence

Einstein stated that the theory of relativity belongs to a class of "principle-theories". As such, it employs an analytic method, which means that the elements of this theory are not based on hypothesis but on empirical discovery. By observing natural processes, we understand their general characteristics, devise mathematical models to describe what we observed, and by analytical means we deduce the necessary conditions that have to be satisfied. Measurement of separate events must satisfy these conditions and match the theory's conclusions.[2]

Tests of special relativity

.svg.png)

Relativity is a falsifiable theory: It makes predictions that can be tested by experiment. In the case of special relativity, these include the principle of relativity, the constancy of the speed of light, and time dilation.[11] The predictions of special relativity have been confirmed in numerous tests since Einstein published his paper in 1905, but three experiments conducted between 1881 and 1938 were critical to its validation. These are the Michelson–Morley experiment, the Kennedy–Thorndike experiment, and the Ives–Stilwell experiment. Einstein derived the Lorentz transformations from first principles in 1905, but these three experiments allow the transformations to be induced from experimental evidence.

Maxwell's equations—the foundation of classical electromagnetism—describe light as a wave that moves with a characteristic velocity. The modern view is that light needs no medium of transmission, but Maxwell and his contemporaries were convinced that light waves were propagated in a medium, analogous to sound propagating in air, and ripples propagating on the surface of a pond. This hypothetical medium was called the luminiferous aether, at rest relative to the "fixed stars" and through which the Earth moves. Fresnel's partial ether dragging hypothesis ruled out the measurement of first-order (v/c) effects, and although observations of second-order effects (v2/c2) were possible in principle, Maxwell thought they were too small to be detected with then-current technology.[12][13]

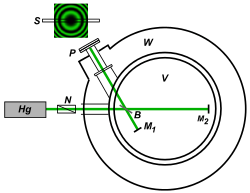

The Michelson–Morley experiment was designed to detect second-order effects of the "aether wind"—the motion of the aether relative to the earth. Michelson designed an instrument called the Michelson interferometer to accomplish this. The apparatus was more than accurate enough to detect the expected effects, but he obtained a null result when the first experiment was conducted in 1881,[14] and again in 1887.[15] Although the failure to detect an aether wind was a disappointment, the results were accepted by the scientific community.[13] In an attempt to salvage the aether paradigm, FitzGerald and Lorentz independently created an ad hoc hypothesis in which the length of material bodies changes according to their motion through the aether.[16] This was the origin of FitzGerald–Lorentz contraction, and their hypothesis had no theoretical basis. The interpretation of the null result of the Michelson–Morley experiment is that the round-trip travel time for light is isotropic (independent of direction), but the result alone is not enough to discount the theory of the aether or validate the predictions of special relativity.[17][18]

While the Michelson–Morley experiment showed that the velocity of light is isotropic, it said nothing about how the magnitude of the velocity changed (if at all) in different inertial frames. The Kennedy–Thorndike experiment was designed to do that, and was first performed in 1932 by Roy Kennedy and Edward Thorndike.[19] They obtained a null result, and concluded that "there is no effect ... unless the velocity of the solar system in space is no more than about half that of the earth in its orbit".[18][20] That possibility was thought to be too coincidental to provide an acceptable explanation, so from the null result of their experiment it was concluded that the round-trip time for light is the same in all inertial reference frames.[17][18]

The Ives–Stilwell experiment was carried out by Herbert Ives and G.R. Stilwell first in 1938[21] and with better accuracy in 1941.[22] It was designed to test the transverse Doppler effect – the redshift of light from a moving source in a direction perpendicular to its velocity—which had been predicted by Einstein in 1905. The strategy was to compare observed Doppler shifts with what was predicted by classical theory, and look for a Lorentz factor correction. Such a correction was observed, from which was concluded that the frequency of a moving atomic clock is altered according to special relativity.[17][18]

Those classic experiments have been repeated many times with increased precision. Other experiments include, for instance, relativistic energy and momentum increase at high velocities, experimental testing of time dilation, and modern searches for Lorentz violations.

Tests of general relativity

General relativity has also been confirmed many times, the classic experiments being the perihelion precession of Mercury's orbit, the deflection of light by the Sun, and the gravitational redshift of light. Other tests confirmed the equivalence principle and frame dragging.

Modern applications

Far from being simply of theoretical interest, relativistic effects are important practical engineering concerns. Satellite-based measurement needs to take into account relativistic effects, as each satellite is in motion relative to an Earth-bound user and is thus in a different frame of reference under the theory of relativity. Global positioning systems such as GPS, GLONASS, and Galileo, must account for all of the relativistic effects, such as the consequences of Earth's gravitational field, in order to work with precision.[23] This is also the case in the high-precision measurement of time.[24] Instruments ranging from electron microscopes to particle accelerators would not work if relativistic considerations were omitted.[25]

See also

References

- Einstein A. (1916), (Translation 1920), New York: H. Holt and Company

- Einstein, Albert (November 28, 1919). . The Times.

- Will, Clifford M (2010). "Relativity". Grolier Multimedia Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2010-08-01.

- Will, Clifford M (2010). "Space-Time Continuum". Grolier Multimedia Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2010-08-01.

- Will, Clifford M (2010). "Fitzgerald–Lorentz contraction". Grolier Multimedia Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2010-08-01.

- Planck, Max (1906), , Physikalische Zeitschrift, 7: 753–761

- Miller, Arthur I. (1981), Albert Einstein's special theory of relativity. Emergence (1905) and early interpretation (1905–1911), Reading: Addison–Wesley, ISBN 978-0-201-04679-3

- Hey, Anthony J.G.; Walters, Patrick (2003). The New Quantum Universe (illustrated, revised ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 227. Bibcode:2003nqu..book.....H. ISBN 978-0-521-56457-1.

- Greene, Brian. "The Theory of Relativity, Then and Now". Retrieved 2015-09-26.

- Feynman, Richard Phillips; Morínigo, Fernando B.; Wagner, William; Pines, David; Hatfield, Brian (2002). Feynman Lectures on Gravitation. West view Press. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-8133-4038-8., Lecture 5

- Roberts, T; Schleif, S; Dlugosz, JM (ed.) (2007). "What is the experimental basis of Special Relativity?". Usenet Physics FAQ. University of California, Riverside. Retrieved 2010-10-31.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Maxwell, James Clerk (1880), , Nature, 21 (535): 314–315, Bibcode:1880Natur..21S.314., doi:10.1038/021314c0

- Pais, Abraham (1982). "Subtle is the Lord ...": The Science and the Life of Albert Einstein (1st ed.). Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press. pp. 111–113. ISBN 978-0-19-280672-7.

- Michelson, Albert A. (1881). . American Journal of Science. 22 (128): 120–129. Bibcode:1881AmJS...22..120M. doi:10.2475/ajs.s3-22.128.120.

- Michelson, Albert A. & Morley, Edward W. (1887). . American Journal of Science. 34 (203): 333–345. Bibcode:1887AmJS...34..333M. doi:10.2475/ajs.s3-34.203.333.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Pais, Abraham (1982). "Subtle is the Lord ...": The Science and the Life of Albert Einstein (1st ed.). Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press. p. 122. ISBN 978-0-19-280672-7.

- Robertson, H.P. (July 1949). "Postulate versus Observation in the Special Theory of Relativity" (PDF). Reviews of Modern Physics. 21 (3): 378–382. Bibcode:1949RvMP...21..378R. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.21.378.

- Taylor, Edwin F.; John Archibald Wheeler (1992). Spacetime physics: Introduction to Special Relativity (2nd ed.). New York: W.H. Freeman. pp. 84–88. ISBN 978-0-7167-2327-1.

- Kennedy, R.J.; Thorndike, E.M. (1932). "Experimental Establishment of the Relativity of Time" (PDF). Physical Review. 42 (3): 400–418. Bibcode:1932PhRv...42..400K. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.42.400.

- Robertson, H.P. (July 1949). "Postulate versus Observation in the Special Theory of Relativity" (PDF). Reviews of Modern Physics. 21 (3): 381. Bibcode:1949RvMP...21..378R. doi:10.1103/revmodphys.21.378.

- Ives, H.E.; Stilwell, G.R. (1938). "An experimental study of the rate of a moving atomic clock". Journal of the Optical Society of America. 28 (7): 215. Bibcode:1938JOSA...28..215I. doi:10.1364/JOSA.28.000215.

- Ives, H.E.; Stilwell, G.R. (1941). "An experimental study of the rate of a moving atomic clock. II". Journal of the Optical Society of America. 31 (5): 369. Bibcode:1941JOSA...31..369I. doi:10.1364/JOSA.31.000369.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-11-05. Retrieved 2015-12-09.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Francis, S.; B. Ramsey; S. Stein; Leitner, J.; Moreau, J.M.; Burns, R.; Nelson, R.A.; Bartholomew, T.R.; Gifford, A. (2002). "Timekeeping and Time Dissemination in a Distributed Space-Based Clock Ensemble" (PDF). Proceedings 34th Annual Precise Time and Time Interval (PTTI) Systems and Applications Meeting: 201–214. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 February 2013. Retrieved 14 April 2013.

- Hey, Tony; Hey, Anthony J. G.; Walters, Patrick (1997). Einstein's Mirror (illustrated ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. x (preface). ISBN 978-0-521-43532-1.

Further reading

- Einstein, Albert (2005). Relativity: The Special and General Theory. Translated by Robert W. Lawson (The masterpiece science ed.). New York: Pi Press. ISBN 978-0-13-186261-6.

- Einstein, Albert (1920). Relativity: The Special and General Theory (PDF). Henry Holt and Company.

- Einstein, Albert; trans. Schilpp; Paul Arthur (1979). Albert Einstein, Autobiographical Notes (A Centennial ed.). La Salle, IL: Open Court Publishing Co. ISBN 978-0-87548-352-8.

- Einstein, Albert (2009). Einstein's Essays in Science. Translated by Alan Harris (Dover ed.). Mineola, NY: Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-47011-5.

- Einstein, Albert (1956) [1922]. The Meaning of Relativity (5 ed.). Princeton University Press.

- The Meaning of Relativity Albert Einstein: Four lectures delivered at Princeton University, May 1921

- How I created the theory of relativity Albert Einstein, December 14, 1922; Physics Today August 1982

- Relativity Sidney Perkowitz Encyclopædia Britannica

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Theory of relativity |

| Wikisource has original works on the topic: Relativity |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikibooks has a book on the topic of: Category:Relativity |

| Wikiversity has learning resources about General relativity |

- Theory of relativity at Curlie

- Relativity Milestones: Timeline of Notable Relativity Scientists and Contributions