Kennedy–Thorndike experiment

The Kennedy–Thorndike experiment, first conducted in 1932 by Roy J. Kennedy and Edward M. Thorndike, is a modified form of the Michelson–Morley experimental procedure, testing special relativity.[1] The modification is to make one arm of the classical Michelson–Morley (MM) apparatus shorter than the other one. While the Michelson–Morley experiment showed that the speed of light is independent of the orientation of the apparatus, the Kennedy–Thorndike experiment showed that it is also independent of the velocity of the apparatus in different inertial frames. It also served as a test to indirectly verify time dilation – while the negative result of the Michelson–Morley experiment can be explained by length contraction alone, the negative result of the Kennedy–Thorndike experiment requires time dilation in addition to length contraction to explain why no phase shifts will be detected while the Earth moves around the Sun. The first direct confirmation of time dilation was achieved by the Ives–Stilwell experiment. Combining the results of those three experiments, the complete Lorentz transformation can be derived.[2]

Improved variants of the Kennedy–Thorndike experiment have been conducted using optical cavities or Lunar Laser Ranging. For a general overview of tests of Lorentz invariance, see Tests of special relativity.

The experiment

The original Michelson–Morley experiment was useful for testing the Lorentz–FitzGerald contraction hypothesis only. Kennedy had already made several increasingly sophisticated versions of the MM experiment through the 1920s when he struck upon a way to test time dilation as well. In their own words:[1]

The principle on which this experiment is based is the simple proposition that if a beam of homogeneous light is split […] into two beams which after traversing paths of different lengths are brought together again, then the relative phases […] will depend […] on the velocity of the apparatus unless the frequency of the light depends […] on the velocity in the way required by relativity.

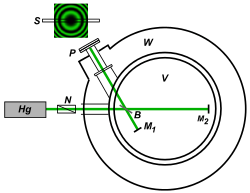

Referring to Fig. 1, key optical components were mounted within vacuum chamber V on a fused quartz base of extremely low coefficient of thermal expansion. A water jacket W kept the temperature regulated to within 0.001 °C. Monochromatic green light from a mercury source Hg passed through a Nicol polarizing prism N before entering the vacuum chamber, and was split by a beam splitter B set at Brewster's angle to prevent unwanted rear surface reflections. The two beams were directed towards two mirrors M1 and M2 which were set at distances as divergent as possible given the coherence length of the 5461 Å mercury line (≈32 cm, allowing a difference in arm length ΔL ≈ 16 cm). The reflected beams recombined to form circular interference fringes which were photographed at P. A slit S allowed multiple exposures across the diameter of the rings to be recorded on a single photographic plate at different times of day.

By making one arm of the experiment much shorter than the other, a change in velocity of the Earth would cause changes in the travel times of the light rays, from which a fringe shift would result unless the frequency of the light source changed to the same degree. In order to determine if such a fringe shift took place, the interferometer was made extremely stable and the interference patterns were photographed for later comparison. The tests were done over a period of many months. As no significant fringe shift was found (corresponding to a velocity of 10±10 km/s within the margin of error), the experimenters concluded that time dilation occurs as predicted by Special relativity.

Theory

Basic theory of the experiment

Although Lorentz–FitzGerald contraction (Lorentz contraction) by itself is fully able to explain the null results of the Michelson–Morley experiment, it is unable by itself to explain the null results of the Kennedy–Thorndike experiment. Lorentz–FitzGerald contraction is given by the formula:

where

- is the proper length (the length of the object in its rest frame),

- is the length observed by an observer in relative motion with respect to the object,

- is the relative velocity between the observer and the moving object, i.e. between the hypothetical aether and the moving object

- is the speed of light,

and the Lorentz factor is defined as

- .

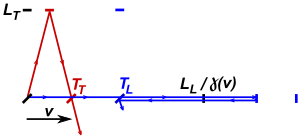

Fig. 2 illustrates a Kennedy–Thorndike apparatus with perpendicular arms and assumes the validity of Lorentz contraction.[3] If the apparatus is motionless with respect to the hypothetical aether, the difference in time that it takes light to traverse the longitudinal and transverse arms is given by:

The time it takes light to traverse back-and-forth along the Lorentz–contracted length of the longitudinal arm is given by:

where T1 is the travel time in direction of motion, T2 in the opposite direction, v is the velocity component with respect to the luminiferous aether, c is the speed of light, and LL the length of the longitudinal interferometer arm. The time it takes light to go across and back the transverse arm is given by:

The difference in time that it takes light to traverse the longitudinal and transverse arms is given by:

Because ΔL=c(TL-TT), the following travel length differences are given (ΔLA being the initial travel length difference and vA the initial velocity of the apparatus, and ΔLB and vB after rotation or velocity change due to Earth's own rotation or its rotation around the Sun):[4]

- .

In order to obtain a negative result, we should have ΔLA−ΔLB=0. However, it can be seen that both formulas only cancel each other as long as the velocities are the same (vA=vB). But if the velocities are different, then ΔLA and ΔLB are no longer equal. (The Michelson–Morley experiment isn't affected by velocity changes since the difference between LL and LT is zero. Therefore, the MM experiment only tests whether the speed of light depends on the orientation of the apparatus.) But in the Kennedy–Thorndike experiment, the lengths LL and LT are different from the outset, so it is also capable of measuring the dependence of the speed of light on the velocity of the apparatus.[2]

According to the previous formula, the travel length difference ΔLA−ΔLB and consequently the expected fringe shift ΔN are given by (λ being the wavelength):

- .

Neglecting magnitudes higher than second order in v/c:

For constant ΔN, i.e. for the fringe shift to be independent of velocity or orientation of the apparatus, it is necessary that the frequency and thus the wavelength λ be modified by the Lorentz factor. This is actually the case when the effect of time dilation on the frequency is considered. Therefore, both length contraction and time dilation are required to explain the negative result of the Kennedy–Thorndike experiment.

Importance for relativity

In 1905, it had been shown by Henri Poincaré and Albert Einstein that the Lorentz transformation must form a group to satisfy the principle of relativity (see History of Lorentz transformations). This requires that length contraction and time dilation have the exact relativistic values. Kennedy and Thorndike now argued that they could derive the complete Lorentz transformation solely from the experimental data of the Michelson–Morley experiment and the Kennedy–Thorndike experiment. But this is not strictly correct, since length contraction and time dilation having their exact relativistic values are sufficient but not necessary for the explanation of both experiments. This is because length contraction solely in the direction of motion is only one possibility to explain the Michelson–Morley experiment. In general, its null result requires that the ratio between transverse and longitudinal lengths corresponds to the Lorentz factor – which includes infinitely many combinations of length changes in the transverse and longitudinal direction. This also affects the role of time dilation in the Kennedy–Thorndike experiment, because its value depends on the value of length contraction used in the analysis of the experiment. Therefore, it's necessary to consider a third experiment, the Ives–Stilwell experiment, in order to derive the Lorentz transformation from experimental data alone.[2]

More precisely: In the framework of the Robertson-Mansouri-Sexl test theory,[2][5] the following scheme can be used to describe the experiments: α represents time changes, β length changes in the direction of motion, and δ length changes perpendicular to the direction of motion. The Michelson–Morley experiment tests the relationship between β and δ, while the Kennedy–Thorndike experiment tests the relationship between α and β. So α depends on β which itself depends on δ, and only combinations of those quantities but not their individual values can be measured in these two experiments. Another experiment is necessary to directly measure the value of one of these quantities. This was actually achieved with the Ives-Stilwell experiment, which measured α as having the value predicted by relativistic time dilation. Combining this value for α with the Kennedy–Thorndike null result shows that β necessarily must assume the value of relativistic length contraction. And combining this value for β with the Michelson–Morley null result shows that δ must be zero. So the necessary components of the Lorentz transformation are provided by experiment, in agreement with the theoretical requirements of group theory.

Recent experiments

Cavity tests

In recent years, Michelson–Morley experiments as well as Kennedy–Thorndike type experiments have been repeated with increased precision using lasers, masers, and cryogenic optical resonators. The bounds on velocity dependence according to the Robertson-Mansouri-Sexl test theory (RMS), which indicates the relation between time dilation and length contraction, have been significantly improved. For instance, the original Kennedy–Thorndike experiment set bounds on RMS velocity dependence of ~10−2, but current limits are in the ~10−8 range.[5]

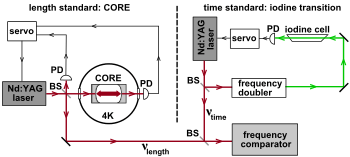

Fig. 3 presents a simplified schematic diagram of Braxmaier et al.'s 2002 repeat of the Kennedy–Thorndike experiment.[6] On the left, photodetectors (PD) monitor the resonance of a sapphire cryogenic optical resonator (CORE) length standard kept at liquid helium temperature to stabilize the frequency of a Nd:YAG laser to 1064 nm. On the right, the 532 nm absorbance line of a low pressure iodine reference is used as a time standard to stabilize the (doubled) frequency of a second Nd:YAG laser.

| Author | Year | Description | Maximum velocity dependence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hils and Hall[7] | 1990 | Comparing the frequency of an optical Fabry–Pérot cavity with that of a laser stabilized to an I2 reference line. | |

| Braxmaier et al.[6] | 2002 | Comparing the frequency of a cryogenic optical resonator with an I2 frequency standard, using two Nd:YAG lasers. | |

| Wolf et al.[8] | 2003 | The frequency of a stationary cryogenic microwave oscillator, consisting of sapphire crystal operating in a whispering gallery mode, is compared to a hydrogen maser whose frequency was compared to caesium and rubidium atomic fountain clocks. Changes during Earth's rotation have been searched for. Data between 2001–2002 was analyzed. | |

| Wolf et al.[9] | 2004 | See Wolf et al. (2003). An active temperature control was implemented. Data between 2002–2003 was analyzed. | |

| Tobar et al.[10] | 2009 | See Wolf et al. (2003). Data between 2002–2008 was analyzed for both sidereal and annual variations. |

Lunar laser ranging

In addition to terrestrial measurements, Kennedy–Thorndike experiments were carried out by Müller & Soffel (1995)[11] and Müller et al. (1999)[12] using Lunar Laser Ranging data, in which the Earth-Moon distance is evaluated to an accuracy of centimeters. If there is a preferred frame of reference and the speed of light depends on the observer's velocity, then anomalous oscillations should be observable in the Earth-Moon distance measurements. Since time dilation is already confirmed to high precision, the observance of such oscillations would demonstrate dependence of the speed of light on the observer’s velocity, as well as direction dependence of length contraction. However, no such oscillations were observed in either study, with a RMS velocity bound of ~10−5,[12] comparable to the bounds set by Hils and Hall (1990). Hence both length contraction and time dilation must have the values predicted by relativity.

References

- Kennedy, R. J.; Thorndike, E. M. (1932). "Experimental Establishment of the Relativity of Time". Physical Review. 42 (3): 400–418. Bibcode:1932PhRv...42..400K. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.42.400.

- Robertson, H. P. (1949). "Postulate versus Observation in the Special Theory of Relativity" (PDF). Reviews of Modern Physics. 21 (3): 378–382. Bibcode:1949RvMP...21..378R. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.21.378.

- Note: In contrast to the following demonstration, which is applicable only to light traveling along perpendicular paths, Kennedy and Thorndike (1932) provided a general argument applicable to light rays following completely arbitrary paths.

- Albert Shadowitz (1988). Special relativity (Reprint of 1968 ed.). Courier Dover Publications. pp. 161. ISBN 0-486-65743-4.

- Mansouri R.; Sexl R.U. (1977). "A test theory of special relativity: III. Second-order tests". Gen. Rel. Gravit. 8 (10): 809–814. Bibcode:1977GReGr...8..809M. doi:10.1007/BF00759585.

- Braxmaier, C.; Müller, H.; Pradl, O.; Mlynek, J.; Peters, A.; Schiller, S. (2002). "Tests of Relativity Using a Cryogenic Optical Resonator" (PDF). Phys. Rev. Lett. 88 (1): 010401. Bibcode:2002PhRvL..88a0401B. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.88.010401. PMID 11800924.

- Hils, Dieter; Hall, J. L. (1990). "Improved Kennedy–Thorndike experiment to test special relativity". Phys. Rev. Lett. 64 (15): 1697–1700. Bibcode:1990PhRvL..64.1697H. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.64.1697. PMID 10041466.

- Wolf; et al. (2003). "Tests of Lorentz Invariance using a Microwave Resonator". Physical Review Letters. 90 (6): 060402. arXiv:gr-qc/0210049. Bibcode:2003PhRvL..90f0402W. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.90.060402. PMID 12633279.

- Wolf, P.; Tobar, M. E.; Bize, S.; Clairon, A.; Luiten, A. N.; Santarelli, G. (2004). "Whispering Gallery Resonators and Tests of Lorentz Invariance". General Relativity and Gravitation. 36 (10): 2351–2372. arXiv:gr-qc/0401017. Bibcode:2004GReGr..36.2351W. doi:10.1023/B:GERG.0000046188.87741.51.

- Tobar, M. E.; Wolf, P.; Bize, S.; Santarelli, G.; Flambaum, V. (2010). "Testing local Lorentz and position invariance and variation of fundamental constants by searching the derivative of the comparison frequency between a cryogenic sapphire oscillator and hydrogen maser". Physical Review D. 81 (2): 022003. arXiv:0912.2803. Bibcode:2010PhRvD..81b2003T. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.81.022003.

- Müller, J.; Soffel, M. H. (1995). "A Kennedy–Thorndike experiment using LLR data". Physics Letters A. 198 (2): 71–73. Bibcode:1995PhLA..198...71M. doi:10.1016/0375-9601(94)01001-B.

- Müller, J., Nordtvedt, K., Schneider, M., Vokrouhlicky, D. (1999). "Improved Determination of Relativistic Quantities from LLR" (PDF). Proceedings of the 11th International Workshop on Laser Ranging Instrumentation. 10: 216–222.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)