Nicomedia

Nicomedia (/ˌnɪkəˈmiːdiə/;[1] Greek: Νικομήδεια, Nikomedeia; modern İzmit) was an ancient Greek city in Turkey. The city was incorporated into the Ottoman Empire with the victory of Sultan Orhan Gazi against the Eastern Roman Empire. In 286 Nicomedia became the eastern and most senior capital city of the Roman Empire (chosen by Diocletian who assumed the title Augustus of the East), a status which the city maintained during the Tetrarchy system (293–324).

French illustration of Nicomedia, 1882 | |

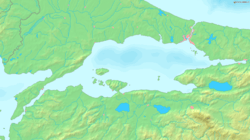

Shown within Turkey  Nicomedia (Sea of Marmara) | |

| Location | Turkey |

|---|---|

| Region | Kocaeli Province |

| Coordinates | 40°45′45″N 29°55′03″E |

The Tetrarchy ended with the Battle of Chrysopolis (Üsküdar) in 324, when Constantine defeated Licinius and became the sole emperor. In 330 Constantine chose for himself the nearby Byzantium (which was renamed Constantinople, modern Istanbul) as the new capital of the Roman Empire.

History

It was founded in 712/11 BC as a Megarian colony and was originally known as Astacus (/ˈæstəkəs/; Ancient Greek: Ἀστακός, "lobster").[2] After being destroyed by Lysimachus,[3] it was rebuilt by Nicomedes I of Bithynia in 264 BC under the name of Nicomedia, and has ever since been one of the most important cities in northwestern Asia Minor. The great military commander Hannibal Barca came to Nicomedia in his final years and committed suicide in nearby Libyssa (Diliskelesi, Gebze). The historian Arrian was born there.

Nicomedia was the metropolis and capital of the Roman province of Bithynia under the Roman Empire. It is referenced repeatedly in Pliny the Younger's Epistles to Trajan during his tenure as governor of Bithynia.[5] Pliny, in his letters, mentions several public buildings of the city such as a senate-house, an aqueduct, a forum, a temple of Cybele, and others, and speaks of a great fire, during which the place suffered much.[6] Diocletian made it the eastern capital city of the Roman Empire in 286 when he introduced the Tetrarchy system.

Persecutions of 303

Nicomedia was at the center of the Diocletianic Persecution of Christians which occurred under Diocletian and his Caesar Galerius. On 23 February 303 AD, the pagan festival of the Terminalia, Diocletian ordered that the newly built church at Nicomedia be razed, its scriptures burnt, and its precious stones seized.[7] The next day he issued his "First Edict Against the Christians," which ordered similar measures to be taken at churches across the Empire.

The destruction of the Nicomedia church incited panic in the city, and at the end of the month a fire destroyed part of Diocletian's palace, followed 16 days later by another fire.[8] Although an investigation was made into the cause of the fires, no party was officially charged, but Galerius placed the blame on the Christians. He oversaw the execution of two palace eunuchs, who he claimed conspired with the Christians to start the fire, followed by six more executions through the end of April 303. Soon after Galerius declared Nicomedia to be unsafe and ostentatiously departed the city for Rome, followed soon after by Diocletian.[8]

Later Empire

Nicomedia remained as the eastern (and most senior) capital of the Roman Empire until co-emperor Licinius was defeated by Constantine the Great at the Battle of Chrysopolis (Üsküdar) in 324. Constantine mainly resided in Nicomedia as his interim capital city for the next six years, until in 330 he declared the nearby Byzantium (which was renamed Constantinople) the new capital. Constantine died in a royal villa in the vicinity of Nicomedia in 337. Owing to its position at the convergence of the Asiatic roads leading to the new capital, Nicomedia retained its importance even after the foundation of Constantinople.[9]

A major earthquake, however, on 24 August 358, caused extensive devastation to Nicomedia, and was followed by a fire which completed the catastrophe. Nicomedia was rebuilt, but on a smaller scale.[10] In the sixth century under Emperor Justinian I the city was extended with new public buildings. Situated on the roads leading to the capital, the city remained a major military center, playing an important role in the Byzantine campaigns against the Caliphate.[11] From inscriptions we learn that in the later period of the empire Nicomedia enjoyed the honour of a Roman colony.[12]

In 451, the local bishopric was promoted to a Metropolitan see under the jurisdiction of the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople.[13] The metropolis of Nicomedia was ranked 7th in the Notitiae Episcopatuum among the metropolises of the patriarchate.[14] In the eighth century the Emperor Constantine V established his court there for a time, when plague broke out in Constantinople and drove him from his capital in 746–47.[15] From the 840s on, Nicomedia was the capital of the thema of the Optimatoi. By that time, most of the old, seawards city had been abandoned and is described by the Persian geographer Ibn Khurdadhbih as lying in ruins, with settlement restricted to the hilltop citadel.[11] In the 1080s, the city served as the main military base for Alexios I Komnenos in his campaigns against the Seljuk Turks, and the First and Second Crusades both encamped there.

The city was briefly held by the Latin Empire following the fall of Constantinople to the Fourth Crusade in 1204: in late 1206 the seneschal Thierry de Loos made it his base, converting the church of Saint Sophia into a fortress; however, the Crusader stronghold was subjected to constant raids by the Emperor of Nicaea Theodore I Laskaris, during which de Loos was captured by Nicaean soldiers; by the summer of 1207 Emperor Henry of Flanders agreed to evacuate Nicomedia in exchange for de Loos and other prisoners Emperor Theodore held.[16] The city remained in Byzantine control for over a century after that, but following the Byzantine defeat at the Battle of Bapheus in 1302, it was threatened by the rising Ottoman beylik. The city was twice sieged and blockaded by the Ottomans (in 1304 and 1330) before finally succumbing in 1337.[11]

Infrastructure

During the Empire, Nicomedia was a cosmopolitan and commercially prosperous city which received all the amenities appropriate for a major Roman city. Nicomedia was well known for having a bountiful water supply from two to three aqueducts,[17] one of which was built in Hellenistic times. Pliny the Younger complains in his Epistulae to Trajan, written in 110 AD, that the Nicomedians wasted 3,518,000 sesterces on an unfinished aqueduct which twice ran into engineering troubles. Trajan instructs him to take steps to complete the aqueduct, and to investigate possible official corruption behind the large waste of money.[18] Under Trajan, there was also a large Roman garrison.[19] Other public amenities included a theatre, a colonnaded street typical of Hellenistic cities and a forum.[20]

The major religious shrine was a temple of Demeter, which stood in a sacred precinct on a hill above the harbor.[5] The city adopted official cults of Rome avidly, there were temples dedicated to the Emperor Commodus,[21] a sacred precinct of the city dedicated to Octavian,[22] and a temple of Roma dedicated during the late-Republic.[5]

The city was sacked in AD 253 by the Goths, but when Diocletian made the city his capital in 283 AD he undertook grand restorations and built an enormous palace, an armory, mint and new shipyards.[5]

Notable natives and residents

- Diocletian

- Arrian

- Saint George

- Saint Barbara

- Saint Panteleimon

- Adrian of Nicomedia

- Anthimus of Nicomedia

- Arsacius of Nicomedia

- Cecropius of Nicomedia

- Juliana of Nicomedia

- Theopemptus of Nicomedia

- Theophylact of Nicomedia

- Michael Psellos (11th-century) Greek writer, philosopher, politician, and historian

- Maximus Planudes (13th-century) Greek scholar, anthologist, translator and grammarian

- Aaron ben Elijah (14th-century) Karaite Jewish philosopher

_by_shakko.jpg) St. Pantaleon

St. Pantaleon Arrian

Arrian_-_Foto_G._Dall'Orto_28-5-2006.jpg) Diocletian

Diocletian.jpg) Licinus

Licinus.jpg)

Remains

.jpg)

The ruins of Nicomedia are buried beneath the densely populated modern city of İzmit, which has largely obstructed comprehensive excavation. Before the urbanization of the 20th century occurred, select ruins of the Roman-era city could be seen, most prominently sections of the Roman defensive walls which surrounded the city and multiple aqueducts which once supplied Nicomedia's water. Other monuments include the foundations of a 2nd-century AD marble nymphaeum on İstanbul street, a large cistern in the city's Jewish cemetery, and parts of the harbor wall.[5]

The 1999 İzmit earthquake, which seriously damaged most of the city, also led to major discoveries of ancient Nicomedia during the subsequent debris clearing. A wealth of ancient statuary was uncovered, including statues of Hercules, Athena, Diocletian and Constantine.[23]

In the years after the earthquake, the Izmit Provincial Cultural Directorate appropriated small areas for excavation, including the site identified as Diocletian's Palace and a nearby Roman theatre. In April 2016 a more extensive excavation of the palace was begun under the supervision of the Kocaeli Museum, which estimated that the site covers 60,000 square meters (196,850 square feet).[24]

See also

- 20,000 Martyrs of Nicomedia

- Nicaea (present-day İznik, another important city in Bithynia, and the interim Byzantine capital city between 1204 and 1261 (Empire of Nicaea) following the Fourth Crusade in 1204, until the recapture of Constantinople by the Byzantines in 1261. Earlier, the site of the Nicene Creed as well as the First Council of Nicaea and Second Council of Nicaea.)

- List of ancient Greek cities

References

- ""Nicomedia" in the American Heritage Dictionary". Archived from the original on 2014-09-30. Retrieved 2012-07-03.

- Peter Levi (ed.). Guide to Greece By Pausanias. p. 232. ISBN 0-14-044225-1.

- Cohen, Getzel M. The Hellenistic settlements in Europe, the islands, and Asia Minor. p. 400. ISBN 0-520-08329-6.

- "Belt Section with Medallions of Constantius II and Faustina". The Walters Art Museum.

- W.L. MacDonald (1976). "NICOMEDIA NW Turkey". The Princeton Encyclopedia of Classical Sites. Princeton University Press.

- Pliny the Younger, Epist. 10.42, 46.

- Timothy D. Barnes (1981). Constantine & Eusebius. p. 22.

- Patricia Southern (2001). The Roman Empire: From Severus to Constantine. p. 168.

- See C. Texier, Asie mineure (Paris, 1839); V. Cuenet, Turquie d'Asie (Paris, 1894).

- See Ammianus Marcellinus 17.7.1–8

- Kazhdan, Alexander, ed. (1991), Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium, Oxford University Press, pp. 1483–1484, ISBN 978-0-19-504652-6

-

- Kiminas, Demetrius (2009). The Ecumenical Patriarchate. Wildside Press LLC. p. 79. ISBN 978-1-4344-5876-6.

- Terezakis, Yorgos. "Diocese of Nicomedia (Ottoman Period)". Εγκυκλοπαίδεια Μείζονος Ελληνισμού, Μ. Ασία. Retrieved 13 November 2012.

- David Turner, The Politics of Despair: The Plague of 746–747 and Iconoclasm in the Byzantine Empire, The Annual of the British School at Athens, Vol. 85 (1990), p428

- Geoffrey de Villehardouin, translated by M. R. B. Shaw, Joinville and Villehardouin: Chronicles of the Crusades (London: Penguin, 1963), pp. 147, 154–56

- Libanius. Oratories. p. 61.7.18.

- Pliny the Younger. Epistulae. p. 10.37 & .38.

- Pliny the Younger. Epistles. p. 10.74.

- Pliny the Younger. Epistles. p. 10.49.

- Dio Cassius. Roman History. p. 73.12.2.

- Cassius Dio. Roman History. p. 51.20.7.

- "Ancient underground city in izmit excites archaeology world". Hürriyet Daily News. 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2018-01-14.

- "Ancient underground city in izmit excites archaeology world". Hürriyet Daily News. 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2018-01-14.

![]()