Pounamu

Pounamu (or "greenstone" in New Zealand English) are several types of hard and durable stone found in southern New Zealand. They are highly valued by the Māori, and hardstone carvings made from pounamu play an important role in Māori culture. Geologically, pounamu are usually nephrite jade, bowenite, or serpentinite, but the Māori classify pounamu by colour and appearance.[2]

The main classifications are kawakawa, kahurangi, īnanga, and tangiwai. The first three are nephrite jade, while tangiwai is a form of bowenite.[3]

- Īnanga pounamu takes its name from a native freshwater fish (Galaxias maculatus) and is pearly-white or grey-green in colour and varies from translucent to opaque.[4]

- Kahurangi pounamu is highly translucent and has a vivid shade of green. It is named after the clearness of the sky and is the rarest variety of pounamu.[5]

- Kawakawa pounamu comes in many shades, often with flecks or inclusions, and is named after the leaves of the native kawakawa tree (Macropiper excelsum). It is the most common variety of pounamu.[6]

- Tangiwai pounamu is clear like glass but in a wide range of shades. The name comes from the word for the tears that come from great sorrow.[7]

In modern usage pounamu almost always refers to nephrite jade. Pounamu is generally found in rivers in specific parts of the South Island as nondescript boulders and stones.

Significance to Māori

Pounamu plays a very important role in Māori culture. It is considered a taonga (treasure) and therefore protected under the Treaty of Waitangi. Pounamu taonga increase in mana (prestige) as they pass from one generation to another. The most prized taonga are those with known histories going back many generations. These are believed to have their own mana and were often given as gifts to seal important agreements.

Pounamu taonga include tools such as toki (adzes), whao (chisels), whao whakakōka (gouges), ripi pounamu (knives), scrapers, awls, hammer stones, and drill points. Hunting tools include matau (fishing hooks) and lures, spear points, and kākā poria (leg rings for fastening captive birds); weapons such as mere (short handled clubs); and ornaments such as pendants (hei-tiki, hei matau and pekapeka), ear pendants (kuru and kapeu), and cloak pins. [8][9] Functional pounamu tools were widely worn for both practical and ornamental reasons, and continued to be worn as purely ornamental pendants (hei kakī) even after they were no longer used as tools.[10]

Pounamu is found only in the South Island of New Zealand, known in Māori as Te Wai Pounamu ("The [land of] Greenstone Water") or Te Wahi Pounamu ("The Place of Greenstone").[11] In 1997 the Crown handed back the ownership of all naturally occurring pounamu to the South Island iwi Ngāi Tahu,[12][13] as part of the Ngāi Tahu Claims Settlement.

Geological formation and location

Pounamu is found on the West Coast, Fiordland and western Southland.[14][15] It is typically recovered from rivers and beaches where it has been transported to after being eroded from the mountains. However, pounamu has also been quarried by Māori from the mountains, even above the snow line (Source??). The group of rocks where pounamu comes from are called ophiolites. Ophiolites are slices of the deep ocean crust and part of the mantle. When these deep mantle rocks (serpentinite) and crustal rock (mafic igneous rocks) are heated up (metamorphosed) together, pounamu can be formed at their contact.[16]

Pounamu has been formed in New Zealand in three main locations. The Dun Mountain Ophiolite Belt has been metamorphosed in western Southland and pounamu from this belt is found along the eastern and northern edge of Fiordland.[17] The Anita Bay Dunite near Milford Sound is a small but highly prized source of pounamu.[18] In the Southern Alps, the Pounamu Ultramafic Belt in the Haast Schist occurs as isolated pods which are eroded and found on West Coast rivers and beaches.[19]

Modern use

Jewellery and other decorative items made from gold and pounamu were particularly fashionable in New Zealand in the Victorian and Edwardian years in the late 19th and early 20th century.[20][21] It continues to be popular among New Zealanders and is often presented as gifts to visitors and to New Zealanders moving overseas.

Fossicking for Pounamu is a cultural activity in New Zealand and allowed only on designated beaches of the West Coast of the South Island (Te Tai o Poutini) and is limited to what can be carried unaided;[22][23] fossicking elsewhere in the Kai Tahu tribal area is illegal, while Nephrite jade can be sourced legally and freely from Marlborough and Nelson. In 2009 David Anthony Saxton and his son Morgan David Saxton were sentenced to two and a half years imprisonment for stealing greenstone, with a helicopter, from the southern West Coast.[24]

Viggo Mortensen, Aragorn in The Lord of the Rings, took to wearing a hei matau around his neck. Michael Hurst of the television programme Hercules was given a large and heavy pounamu manaia pendant necklace which he wore on the programme. During a particularly energetic action scene the pendant bumped his teeth. The producers felt the ornament suited the nature of the programme yet considered it a safety risk, and had it replaced with a latex replica.

In the 2016 animated movie Moana, Te Fiti's heart was a pounamu stone.

Gallery

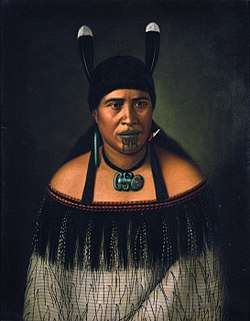

Māori woman with kiwi feather cloak and hei-tiki pendant.

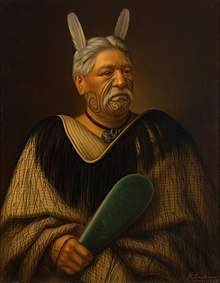

Māori woman with kiwi feather cloak and hei-tiki pendant. Māori chief holding a mere.

Māori chief holding a mere. Māori woman with tattooed chin wearing a pekapeka pendant.

Māori woman with tattooed chin wearing a pekapeka pendant. Hinepare, a woman of the Ngāti Kahungunu tribe. She is wearing a pounamu hei-tiki around her neck, and one pounamu earring and one shark tooth earring

Hinepare, a woman of the Ngāti Kahungunu tribe. She is wearing a pounamu hei-tiki around her neck, and one pounamu earring and one shark tooth earring- Ear pendant (pekapeka), Māori people, pounamu and red sealing wax

.jpg) Kataore, Mere pounamu (42 cm x 12 cm) named after a Ngāi Tahuchief killed by Te Rauparaha in the 1830s. Gifted by Riwai Te Ahu to Sir George Grey.

Kataore, Mere pounamu (42 cm x 12 cm) named after a Ngāi Tahuchief killed by Te Rauparaha in the 1830s. Gifted by Riwai Te Ahu to Sir George Grey. A portrait of Wahanui Reihana Te Huatare carrying a mere and wearing a heitiki made of pounamu

A portrait of Wahanui Reihana Te Huatare carrying a mere and wearing a heitiki made of pounamu A portrait of Rangi Topeora, wearing numerous pounamu items.

A portrait of Rangi Topeora, wearing numerous pounamu items. Nephrite pounamu hei-tiki

Nephrite pounamu hei-tiki- A kuru (straight earring). Kapeu are similar, but with curved ends, and are also used as teething aids.[25]

- A kākā pōria, a bird leg ring used to fasten decoy birds used in hunting.[26]

See also

- Greenstone (disambiguation)

- Hei-tiki

- Lingling-o

References

- "The Greenstone Waters, New Zealand". NASA. 22 May 2010. Retrieved 28 November 2017.

- "Pounamu – An iconic stone". Kura Pounamu Treasured stone of Aotearoa New Zealand. Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. Retrieved 21 November 2010.

- Keane, Basil (2 March 2009). "Pounamu – jade or greenstone – Pounamu – several names". Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Ministry for Culture & Heritage. Retrieved 21 November 2010.

- "Inanga pounamu". Kura Pounamu Treasured stone of Aotearoa New Zealand. Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. Retrieved 25 March 2019.

- "Kahurangi pounamu". Kura Pounamu Treasured stone of Aotearoa New Zealand. Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. Retrieved 25 March 2019.

- "Kawakawa pounamu". Kura Pounamu Treasured stone of Aotearoa New Zealand. Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. Retrieved 25 March 2019.

- "Tangiwai pounamu". Kura Pounamu Treasured stone of Aotearoa New Zealand. Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. Retrieved 25 March 2019.

- "Pounamu taonga". Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. Retrieved 25 March 2019.

- Keane, Basil (2 March 2009). "Pounamu – jade or greenstone – Implements and adornment". Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. New Zealand Ministry for Culture & Heritage. Retrieved 21 November 2010.

- Chris D. Paulin. "Porotaka hei matau — a traditional Māori tool?". Tuhinga. Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. 20: 15–21.

- "Māori names for North and South Islands approved". RNZ National. 10 October 2013. Retrieved 28 November 2017.

- "Pounamu Management Plan", Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu

- "Ngāi Tahu and pounamu", Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand

- Best, Elsdon (1912). The Stone Implements of the Maori. Government Printer. p. 410.

- Coleman, Robert Griffin (1966). New Zealand serpentinites and associated metasomatic rocks. Dept. of Scientific and Industrial Research, N.Z. Geological Survey. p. 101.

- Adams, C.J.; Beck, R.J.; Campbell, H.J. (2007). "Characterisation and origin of New Zealand nephrite jade using its strontium isotopic signature". Lithos. 97 (3–4): 307–322. doi:10.1016/j.lithos.2007.01.001. ISSN 0024-4937.

- Coombs, D. S.; Landis, C. A.; Norris, R. J.; Sinton, J. M.; Borns, D. J.; Craw, D. (1976). "The Dun Mountain ophiolite belt, New Zealand, its tectonic setting, constitution, and origin, with special reference to the southern portion". American Journal of Science. 276 (5): 561–603. doi:10.2475/ajs.276.5.561. ISSN 0002-9599.

- Coutts, P. J. F. (1971). "Greenstone: the prehistoric exploitation of bowenite from Anita Bay, Milford Sound". The Journal of the Polynesian Society. 80 (1): 42–73.

- Cooper, A.F.; Reay, A. (1983). "Lithology, field relationships, and structure of the Pounamu Ultramafics from the Whitcombe and Hokitika Rivers, Westland, New Zealand". New Zealand Journal of Geology and Geophysics. 26 (4): 359–379. doi:10.1080/00288306.1983.10422254. ISSN 0028-8306.

- "Pounamu – a special gift". Kura Pounamu Treasured stone of Aotearoa New Zealand. Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. Retrieved 21 November 2010.

- "Pounamu items from the history collection". Collections Online. Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. Retrieved 21 November 2010.

- "Greenstone rules". Otago Daily Times Online News. 2009-02-07. Retrieved 2020-01-15.

- "Ngāi Tahu Pounamu Resource Management" (PDF). Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu. Retrieved 16 January 2020.

- "Greenstone thieves sent to prison". www.stuff.co.nz.

- http://collections.tepapa.govt.nz/Topic/1988

- http://collections.tepapa.govt.nz/Topic/1989

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to New Zealand greenstone. |

- Photos of 40 Pounamu varieties with accompanying information

- Pounamu, Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu

- "Pounamu – jade or greenstone" in Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand

- Examples of pounamu taonga (Māori treasures) from the collection of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

- First over the Alps: The epic of Raureka and the Greenstone by James Cowan (eText)

- Photo of woman wearing a greenstone neck pendant

- Photo of greenstone tiki

- Photo of greenstone mere

- H. D. Skinner, Otago University Museum (1936). "New Zealand Greenstone". Transactions and Proceedings of the Royal Society of New Zealand. 65: 211–220.

- F. J. Turner, Otago University (1936). "Geological Investigation of the Nephrites, Serpentines, and Related "Greenstones" used by the Maoris of Otago and South Canterbury". Transactions and Proceedings of the Royal Society of New Zealand. 65: 187–210.