Network length (transport)

In transport terminology, network length (or, less often, system length) refers to the total length of a transport network, and commonly also refers to the length of any fixed infrastructure associated with the network.

A measurement can be made of the network length of various different modes of transport, including rail, bus, road and air. The measurement may focus on one of a number of specific characteristics, such as route length, line length or track length.

Lines and routes

Continental European and Scandinavian transport network analysts and planners have long had a professional practice of using the following terminology (in their own languages) to draw a distinction between:

- a line – namely "an operational element of [a] public transport system";[1] and

- a route – as in "the route that [a] bus or rail vehicle follows through the city".[1]

In 2000, this terminology was adopted by an English language best practice guide to public transport, to minimise the risk of confusion.[1][2] Since then, a number of other English language specialist publications have adopted the same terminology, for the same reason.[1][3][4] The terminology is therefore also used in this article.

Route length

The route length of a transport network is the sum of the lengths of all routes in the network,[5] such as railways, road sections or air sectors. The U.S. Department of Transportation's Federal Transit Administration has also referred to this as "Directional Route Miles (DRM)".[6] Where a network is made up of railways, route length has also been defined, by at least one source, as the sum of the distances (in kilometres) between the midpoints of all stations on the network.[7]

In a measurement of route length, each route is counted only once,[5] regardless of how many lines pass over it, and regardless of whether it is single track or multi track, single carriageway or dual carriageway.[6]

If a transport network is made up of tangible routes owned or operated by the operator of the network (such as railways), then its route length is therefore the total length of the network's revenue earning fixed infrastructure.

Line length

In scheduled transport, a calculation may also be made of network's line length, which is the sum of the lengths of all of the lines in the network. Any route in the network that is shared by multiple lines is therefore counted more than once. As a result, the line length of a transport network is always greater than or equal to its route length.

Track length

If a network is made up of railways, tramways, or a combination of the two, its track length may also be calculated. The track length of a rail network is the combined length of all tracks in the network. Thus, a double track route will have a track length twice as long as its route length.[7]

Calculation example

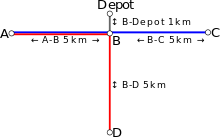

To illustrate how the three different calculations of network length are performed, here is a simple example:

- The tramway (streetcar) network of a small town has two lines.

- Maps of the network show line 1 in blue, and line 2 in red.

- Both lines begin at point A, and run on a common route 5 km (3.1 mi) long to point B.

- At point B, the two lines divide.

- Line 1 continues a further 5 km from point B to a terminus at point C.

- Line 2 similarly continues a further 5 km from point B, but to a different terminus, at point D.

- The entire network is double tracked, apart from a 1 km (0.62 mi) long single non-revenue track from point B to the depot (car barn).

The route length is:

5 km (A → B) + 5 km (B → C) + 5 km (B → D) ------- 15 km

The line length is:

10 km (A → B → C, line 1) + 10 km (A → B → D, line 2) ------- 20 km

The track length is:

10 km (A → B, double track) + 10 km (B → C, double track) + 10 km (B → D, double track) + 1 km (non-passenger carrying) ------- 31 km

See also

- Heuristic routing

- Interplanetary Transport Network

- Line length – about that expression as used in typography

- Routing

- Transportation network (graph theory)

References

- Nielsen, Gustav (2005). Public transport – Planning the networks. HiTrans Best practice guide 2. Stavanger, Norway: HiTrans. p. 94. ISBN 8299011132.

- Terzis, George; Last, Andrew (2000). Urban Interchanges - A Good Practice Guide: Final Report prepared for EC DG VII (PDF). Woking, Surrey, UK: MVA Limited.

- Mees, P; Stone, J; Imran, M; Nielsen, G (2010). Public transport network planning: a guide to best practice in NZ cities (PDF). Research report 396. Wellington: New Zealand Transport Agency. p. 20. ISBN 9780478352917.

- Dodson, Jago; Mees, Paul; Stone, John; Burke, Matthew (2011). The Principles of Public Transport Network Planning: A review of the emerging literature with select examples (PDF). Urban Research Program Issues Paper 15. Brisbane: Griffith University. p. 5. ISBN 9781921760365.

- "Chapter 19: Railways". Statistical Year Book, India 2013. New Delhi: Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, Government of India. 2013. paragraph 19.20. Retrieved 25 November 2013. External link in

|chapter=(help) - "National Transit Database Glossary". U.S. Department of Transportation Federal Transit Administration. 18 October 2013. Archived from the original on 13 November 2013. Retrieved 30 November 2013.

- Review of Developments in Transport in Asia and the Pacific 2007: Data and Trends (2nd revised ed.). Bangkok: United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific. 2008. p. 123. ISBN 9789211205343.