Netherlands in the Roman era

For around 450 years, from around 55 BC to around 410 AD, the southern part of the Netherlands was integrated into the Roman Empire. During this time the Romans in the Netherlands had an enormous influence on the lives and culture of the people who lived in the Netherlands at the time and (indirectly) on the generations that followed.[1]

Early history

During the Gallic Wars, the area south and west of the Rhine was conquered by Roman forces under Julius Caesar in a series of campaigns from 57 BC to 53 BC.[2] The approximately 450 years of Roman rule that followed would profoundly change the Netherlands.

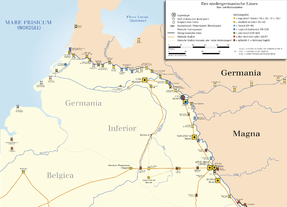

Starting about 15 BC, the Rhine in the Netherlands came to be defended by the Lower Limes Germanicus. After a series of military actions, the Rhine became fixed around 12 AD as Rome's northern frontier on the European mainland. A number of towns and developments would arise along this line.

The area to the south would be integrated into the Roman Empire. At first part of Gallia Belgica, this area became part of the province of Germania Inferior. The tribes already within, or relocated to, this area became part of the Roman Empire.

The area to the north of the Rhine, inhabited by the Frisii and the Chauci, remained outside Roman rule but not its presence and control. The Frisii were initially "won over" by Drusus, suggesting a Roman suzerainty was imposed by Augustus on the coastal areas north of the Rhine river.[3] Over the course of time the Frisii would provide Roman auxiliaries through treaty obligations, but the tribe would also fight the Romans in concert with other Germanic tribes (finally, in 296 the Frisii were relocated in Flanders and disappeared from recorded history).[4]

Native tribes

During the Gallic Wars, the Belgic area south of the Oude Rijn and west of the Rhine was conquered by Roman forces under Julius Caesar in a series of campaigns from 57 BC to 53 BC.[5] He established the principle that this river, which runs through the Netherlands, defined a natural boundary between Gaul and Germania magna. But the Rhine was not a strong border, and he made it clear that there was a part of Belgic Gaul where many of the local tribes were "Germani cisrhenani", or in other cases, of mixed origin. The approximately 450 years of Roman rule that followed would profoundly change the area that would become the Netherlands. Very often this involved large-scale conflict with the "free Germans" over the Rhine.

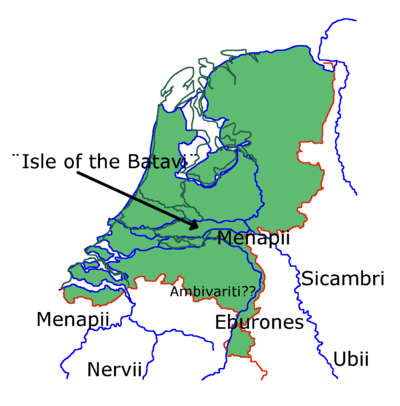

When Caesar arrived, various tribes were located in the area of the Netherlands, residing in the inhabitable higher parts, especially in the east and south. These tribes did not leave behind written records, so all the information known about them during this pre-Roman period is based on what the Romans and Greeks wrote about them. Julius Caesar himself, in his commentary Commentarii de Bello Gallico wrote in detail only about the southern area which he conquered. Two or three tribes who he described as living in what is now the Netherlands were:

- The Menapii, a Belgic tribe who stretched from the Flemish coast, through the south of the river deltas, and as far as the modern German border. In terms of modern Dutch provinces this means at least the south of Zeeland, at least the north of North Brabant, at least the southeast of Gelderland, and possible the south of South Holland. In later Roman times this territory seems to have been divided or reduced, so that it became mainly contained in what is now western Belgium.

- The Eburones, the largest of the Germani Cisrhenani group, whose territory stretched covered a large area between the rivers Maas and Rhine, and also apparently stretched close to the delta, giving them a border with the Menapii. Their territory may have stretched into Gelderland. Caesar claimed to have destroyed the name of the Eburones, but in Roman times Tacitus reports that the Germani Cisrhenani had taken up a new name, the Tungri. While exact borders are not known the territory of the Eburones, and later the Tungri, (the "Civitas Tungrorum") included all or most of the modern provinces of Dutch Limburg, and North Brabant. The part in North Brabant was apparently within what became known as Toxandria, the home of the Texuandri.

- The Ambivariti were apparently a smaller tribe, perhaps part of the Eburones, or Menapii, who Caesar mentions in passing as living west of the Maas, and therefore somewhere in or near North Brabant. (It is possible they lived in what is now Belgium.)

In the delta itself, Caesar makes a passing comment about the Insula Batavorum ("Island of the Batavi") in the Rhine river, without discussing who lived there. Later, in imperial times, a tribe called the Batavi became very important in this region. The island's easternmost point is at a split in the Rhine, one arm being the Waal the other the Lower Rhine/Old Rhine (hence the Latin name [6] Much later Tacitus wrote that they had originally been a tribe of the Chatti, a tribe in Germany never mentioned by Caesar.[7] However, archaeologists find evidence of continuity, and suggest that the Chattic group may have been a small group, moving into a pre-existing (and possibly non-Germanic) people, who could even have been part of a known group such as the Eburones.[8]

| Tribes named by Julius Caesar | Tribes during Roman empire |

|---|---|

|

|

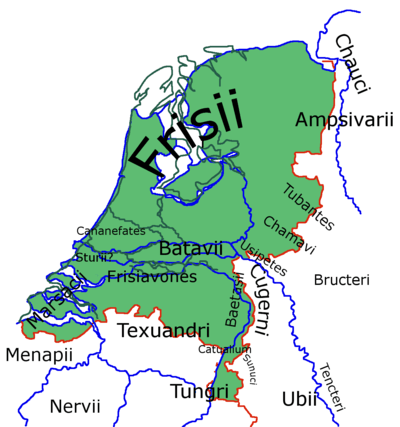

Other tribes who eventually inhabited the "Gaulish" islands in the delta during Roman times are mentioned by Pliny the Elder:[9]

- The Cananefates, whom Tacitus says were similar to the Batavians in their ancestry (and so presumably came from Germany). These lived to the west of the Batavi, sharing the same island, in what is today the province of South Holland.

- The Frisii, who also inhabited the Netherlands north of the delta, and thus covered a major part of the modern Netherlands, not only in modern Friesland, but also in North Holland and at least in parts of all the other northern Dutch provinces today.

- The Chauci, whose main territory was the north sea coast of Germany, bordering the Frisii on their east. They are thought to be ancestors of the later Saxons, and apparently only held a small part of the modern Netherlands in Roman times.

- The Frisiabones, who Pliny also counted as a people living in Gallia Belgica, to the south of the delta. They probably therefore lived in the north of North Brabant, perhaps stretching into Gelderland and South Holland.

- The Marsacii, who Tacitus refers to as neighbours of the Batavi. Pliny also apparently mentioned these as stretching on to the Flemish coast, and they probably inhabited what is today the province of Zeeland.

- The Sturii, who are not known from any other sources, but are thought to have lived near the Marsacii, therefore in modern Zeeland or South Holland.

As mentioned above, the northern Netherlands, above the Old Rhine, was dominated by the Frisii, with perhaps a small penetration of Chauci. While this area was not officially part of the empire for any long periods, military conscription and other impositions were made for long periods upon the Frisii. Several smaller tribes are known from the eastern Netherlands, north of the Rhine:

- The Tuihanti (or Tubantes) from Twenthe in Overijssel, had units serving in the Roman army in Britain.

- The Chamavi, from Hamaland in northern Gelderland, became one of the first tribes to be named as Frankish (see below).

- The Salians, also Franks, probably originated in Salland in Overijssel, before they moved into the empire, forced by Saxons in the 4th century, first into Batavia, and then into Toxandria.

- South of the Chamavi and on the Rhine the Usipetes lived for some time. Caesar reported that them already in his time as newcomers from the east. Eventually they appear to have been forced southeast under pressure from the Frankish Chamavi and Chatuarii.

In the south of the Netherlands the Texuandri inhabited most of North Brabant. The modern province of Limburg, with the Maas running through it, appears to have been inhabited by (from north to south) the Baetasii, the Catualini, the Sunuci and the Tungri.

Batavian revolt

About 38 BC, a pro-Roman faction of the Chatti (a Germanic tribe located east of the Rhine) was settled by Agrippa in an area south of the Rhine, now thought to be the Betuwe area. They took on the name of the people already living there—the Batavians.[2]

The relationship with the original inhabitants was on the whole quite good; many Batavians even served in the Roman cavalry. Batavian culture was influenced by the Roman one, resulting among other things in Roman-style temples such as the one in Elst, dedicated to local gods. Also the trade flourished: the salt used in the Roman empire was won from the North Sea and remains are found across the whole Roman empire.

However, this did not prevent the Batavian rebellion of 69 AD, a very successful revolt under the leadership of Batavian Gaius Julius Civilis. Forty castella were burnt down because the Romans violated the rights of the Batavian leaders by taking young Batavians as their slaves.[10]

Other Roman soldiers (like those in Xanten and the auxiliary troops of Batavians and Cananefates from the legions of Vitellius) joined the revolt, which split the northern part of the Roman army. In April 70, Vespasianus sent a few legions to stop the revolt. Their commander, Petilius Cerialis, eventually defeated the Batavians and started negotiations with Julius Civilis on his home ground, somewhere between the Waal and the Maas near Noviomagus (Nijmegen) or—as the Batavians probably called it—Batavodurum.[11]

Roman settlements in the Netherlands

During their stay in Germania Inferior, the Romans established a number of towns and smaller settlements in the Netherlands and reinforced the Limes Germanicus with military forts. More notable towns include Ulpia Noviomagus Batavorum (modern Nijmegen) and Forum Hadriani (Voorburg).

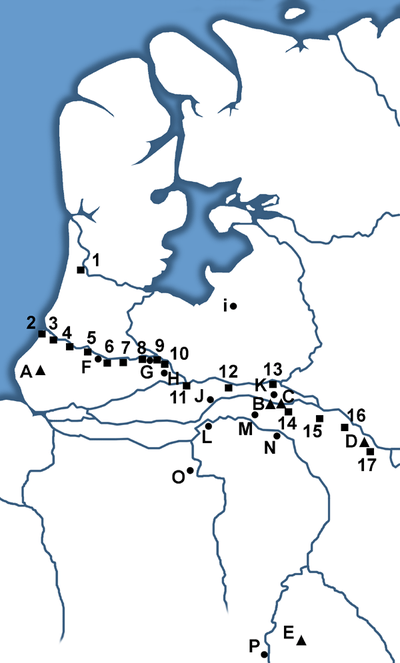

Roman forts in the Netherlands (squares on the map)

- Flevum (at modern Velsen) A harbour has been found here as well. (Disputed)

- Lugdunum Batavorum (Brittenburg at modern Katwijk aan Zee)

- Praetorium Agrippinae (at modern Valkenburg)

- Matilo (in the modern Roomburg area of Leiden)

- Albaniana (at modern Alphen aan den Rijn)

- Fort of an unknown name (near Bodegraven)

- Laurium (at modern Woerden)

- A fort perhaps called Fletio (at modern Vleuten)

- Traiectum (in modern Utrecht)

- Fectio (Vechten)

- Levefanum (at modern Wijk bij Duurstede)

- Carvo (at modern Kesteren in Neder-Betuwe)

- Fort of an unknown name at (Meinerswijk)

- Noviomagus (in modern (Nijmegen)

Towns in the Netherlands (triangles on the map)

A) Forum Hadriani, a.k.a. Aellium Cananefatum (modern Voorburg)

B) Ulpia Noviomagus Batavorum, a.k.a. Colonia Ulpia Noviomagus, (modern Nijmegen)

C) Batavorum (in modern Nijmegen)

D) Colonia Ulpia Trajana (in modern Xanten, Germany)

E) Coriovallum (in modern Heerlen)

Settlements or posts (circles on the map)

F) Nigrum Pullum (modern Zwammerdam)

G) settlement of an unknown name on the Leidsche Rijn

H) Haltna (modern Houten)

I) settlement of an unknown name (modern Ermelo)

J) settlement of an unknown name (modern Tiel)

K) Roman temples (modern Elst, Overbetuwe)

L) Temple possibly devoted to Hercules Magusannus (modern Kessel, North Brabant)

M) Temple (at an area called "De lithse Ham" near Maren-Kessel, now part of Oss)[12]

N) Ceuclum (modern Cuijk)

O) Roman era tombs 2km south of town center (modern Esch)

P) Trajectum ad Mosam, also known as Mosae Trajectum, (modern Maastricht)

Not marked on the map: a possible fort in modern Venlo and a settlement called Catualium[13] near modern Roermond

Franks

In the 3rd century the Franks, a warrior Germanic tribe, started to appear in the Netherlands. Their attacks happened in a time period with a catastrophic sea invasion of the area.

Another change was irreversible. During transgression phases, the sea is more aggressive than under normal circumstances. The third century saw the beginning of an era of increased violence from the sea. The canal between Lake Flevo and the Wadden Sea widened and the mud-flats of the north become wetlands. The Frisians and Chauci increased the height of the terps (the mounds on the alluvial plain on which they lived) but in vain. It seems that their country was largely depopulated, and the Frisians disappear from our sources. (It is unlikely that the inhabitants of modern Friesland are related to the ancient Frisians.).....The cause of this devastation (in Frisian lands) is easy to find: raids of a new Germanic tribe, the Franks.[14]

Frankish identity emerged at the first half of the 3rd century out of various earlier, smaller Germanic groups, including the Salii, Sicambri, Chamavi, Bructeri, Chatti, Chattuarii, Ampsivarii, Tencteri, Ubii, Batavi and the Tungri, who inhabited the lower and middle Rhine valley between the Zuyderzee and the river Lahn and extended eastwards as far as the Weser, but were the most densely settled around the IJssel and between the Lippe and the Sieg. The Frankish confederation probably began to coalesce in the 210s.[15]

Franks appear in Roman texts as both allies and enemies (laeti or dediticii). In 288 the emperor Maximian defeated the Salian Franks, Chamavi, Frisians and other Germans living along the Rhine and moved them to Germania inferior to provide manpower and prevent the settlement of other Germanic tribes.[16][17] In 292 Constantius defeated the Franks who had settled at the mouth of the Rhine. These were moved to the nearby region of Toxandria.[18] Around 310, the Franks had the region of the Scheldt river (present day west Flanders and southwest Netherlands) under control, and were raiding the Channel, disrupting transportation to Britain. Roman forces pacified the region, but did not expel the Franks, who continued to be feared as pirates along the shores at least until the time of Julian the Apostate (358), when Salian Franks were granted to settle as foederati in Toxandria, according to Ammianus Marcellinus.[19]

At the beginning of the 5th century, the Franks became the most important ethnic group in the region, just before the end of the Western Roman Empire.

See also

Notes

- The exact location of the shifting coastline in Roman times is unknown.

References

- Much of this article is derived from the Dutch Wikipedia article called Romeinen in Nederland

- Jona Lendering, "Conquest and Defeat", "Germania Inferior", https://www.livius.org/ga-gh/germania/inferior.htm#Conquest

- Lucius Cassius Dio.Book LIV, Ch 32 p. 365 <https://books.google.com/books?id=wa5fAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA365>

- Grane, Thomas (2007), "From Gallienus to Probus - Three decades of turmoil and recovery", The Roman Empire and Southern Scandinavia–a Northern Connection! (PhD thesis), Copenhagen: University of Copenhagen, p. 109

- Lendering, Jona, "Germania Inferior", Livius.org. Retrieved 6 October 2011.

- Caes. Gal. 4.10

- Cornelius Tacitus, Germany and its Tribes 1.29

- Nico Roymans, Ethnic Identity and Imperial Power. The Batavians in the Early Roman Empire. Amsterdam Archaeological Studies 10. Amsterdam, 2004. Chapter 4. Also see page 249.

- Plin. Nat. 4.29

- Jona Lendering, "The Batavian Revolt"

- Historiae by Tacitus, 1st century AD. Translation into Dutch by the Radboud Universiteit, Nijmegen Archived 2005-11-03 at the Wayback Machine

- http://www.omroepbrabant.nl/?news/56926822/Romeinse+vondsten+in+de+Lithse+Ham.aspx

- https://www.livius.org/articles/place/catualium-heel/

- Jona Lendering: Germania inferior (Livius.org)]

- Charles William Previté-Orton. The Shorter Cambridge Medieval History, vol. I. p. 151.

- Williams, 50–51.

- Barnes, Constantine and Eusebius, 7.

- Howorth 1884, pp. 215–216

- Previté-Orton. The Shorter Cambridge Medieval History, vol. I. pp. 51–52.

Bibliography

- Bernard Colebrander, MUST (redactie), Limes Atlas, (Uitgeverij 010, 2005 Rotterdam)

- Excerpta Romana. De bronnen der Romeinse Geschiedenis van Nederland