Nadia Comăneci

Nadia Elena Comăneci (UK: /ˌkɒməˈnɛtʃ(i)/,[2][3] US: /ˈkoʊməniːtʃ/,[3] Romanian: [ˈnadi.a koməˈnetʃʲ] (![]()

| Nadia Comăneci | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

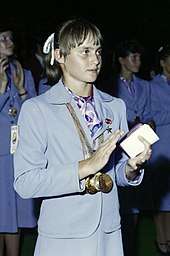

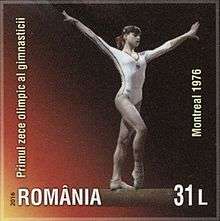

Comăneci at the 1976 Summer Olympics | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal information | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Full name | Nadia Elena Comăneci | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nickname(s) | Nana | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Country represented | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | 12 November 1961 Onești, Romania[1] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Spouse | Bart Conner | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Height | 5 ft 4 in (1.63 m)[1] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Discipline | Women's artistic gymnastics | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Level | Senior Elite | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Gym | National Training Center | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| College team | Politehnica University of Bucharest | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Former coach(es) | Béla Károlyi Márta Károlyi | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Choreographer | Geza Pozsar | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Eponymous skills | Comăneci salto (uneven bars) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Retired | 7 May 1984 (official) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Medal record

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Comăneci is one of the world's best-known gymnasts and is credited with popularizing the sport around the globe.[5] In 2000, she was named as one of the Athletes of the 20th Century by the Laureus World Sports Academy.[6] She has lived in the United States since 1989, when she defected from then-Communist Romania before its revolution in December that year. She later worked with and married American Olympic gold medal gymnast Bart Conner, who set up his own school. In 2001 she became a naturalized United States citizen, and has dual citizenship, also maintaining her Romanian citizenship.

Early life

Nadia Elena Comăneci was born on November 12, 1961, in Onești, a small town in the Carpathian Mountains, in Bacău County, Romania, in the historical region of Western Moldavia.[7][8] She was born to Gheorghe (1936–2012) and Ștefania Comăneci, and has a younger brother.[9] Her parents separated in the 1970s, and her father later moved to Bucharest, the capital.[10] She and her younger brother Adrian were raised in the Romanian Orthodox Church.[11] In a 2011 interview, Nadia's mother Ștefania said that she enrolled her daughter into gymnastics classes because she was a child who was so full of energy and active that she was difficult to manage.[12] After years of top-level athletic competition, Comăneci graduated from Politehnica University of Bucharest with a degree in sports education, which gave her the qualifications to coach gymnastics.[13]

Early gymnastics career

Comăneci began gymnastics in kindergarten with a local team called Flacăra ("The Flame"), with coaches Duncan and Munteanu.[14][15] At age 6, she was chosen to attend Béla Károlyi's experimental gymnastics school after Károlyi spotted her and a friend turning cartwheels in a schoolyard.[16][17] Károlyi was looking for gymnasts he could train from a young age. When recess ended, the girls quickly went inside and Károlyi went around the classrooms trying to find them; he eventually spotted Comăneci. (The other girl, Viorica Dumitru, developed in a different direction and became one of Romania's top ballerinas.)

By 1968, when she was seven, Comăneci had started training with Károlyi. She was one of the first students at the gymnastics school established in Onești by Béla and his wife, Márta. As a resident of the town, Comăneci was able to live at home for many years; most of the other students boarded at the school.

In 1970, Comăneci began competing as a member of her hometown team and, at age nine, became the youngest gymnast ever to win the Romanian Nationals. In 1971, she participated in her first international competition, a dual junior meet between Romania and Yugoslavia, winning her first all-around title, and contributing to the team gold. For the next few years, she competed as a junior in numerous national contests in Romania and dual meets with countries such as Hungary, Italy, and Poland.[18] At the age of 11, in 1973, she won the all-around gold, as well as the vault and uneven bars titles, at the Junior Friendship Tournament (Druzhba), an important international meet for junior gymnasts.[18][19]

Comăneci's first major international success came at the age of 13, when she nearly swept the 1975 European Women's Artistic Gymnastics Championships in Skien, Norway. She won the all-around and gold medals in every event but the floor exercise, in which she placed second. She continued to enjoy success that year, winning the all-around at the "Champions All" competition, and placing first in the all-around, vault, beam, and bars at the Romanian National Championships. In the pre-Olympic test event in Montreal, Comăneci won the all-around and the balance beam golds, as well as silvers in the vault, floor, and bars. Accomplished Soviet gymnast Nellie Kim won the golds in those events and was one of Comăneci's greatest rivals during the next five years.[18]

1976

American Cup

In March 1976, Comăneci competed in the inaugural edition of the American Cup at Madison Square Garden in Manhattan. She received rare scores of 10, which signified a perfect routine without any deductions, for her vault in the preliminary stage and for her floor exercise routine in the final of the all-around competition, which she won.[20] During this competition, Comăneci met American gymnast Bart Conner for the first time. While he remembered this meeting, Comăneci noted in her memoirs that she had to be reminded of it later in life. She was 14 and Conner was celebrating his 18th birthday.[21] They both won a silver cup and were photographed together. A few months later, they participated in the 1976 Summer Olympics that Comăneci dominated, while Conner was a marginal figure. Conner later said, "Nobody knew me, and [Comăneci] certainly didn't pay attention to me."[22]

Summer Olympics in Montreal

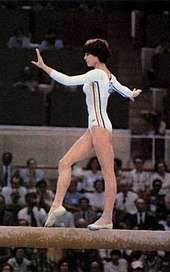

At Montreal [Comăneci] received four of her seven 10s on the uneven bars. The apparatus demands such a spectacular burst of energy in such a short time—only 23 seconds—that it attracts the most fanfare. But it is on the beam that her work seems more representative of her unbelievable skill. She scored three of her seven 10s on the beam. Her hands speak there as much as her body. Her pace magnifies her balance. Her command and distance hush the crowd.

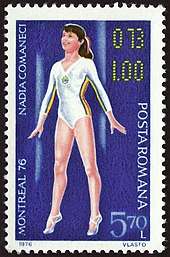

On 18 July 1976, Comăneci made history at the Montreal Olympics. During the team compulsory portion of the competition, she was awarded the first perfect 10 in Olympic gymnastics for her routine on the uneven bars.[23][24][25] But Omega SA, the traditional Olympics scoreboard manufacturer, had been led to believe that competitors could not receive a perfect ten, and had not programmed the scoreboard to display that score.[26] Comăneci's perfect 10 thus appeared as "1.00," the only means by which the judges could indicate that she had received a 10.[27][25]

During the remainder of the Montreal Games, Comăneci earned six additional "10s". She won gold medals for the individual all-around, the balance beam and uneven bars. She also won a bronze for the floor exercise and a silver as part of the team all-around.[28] Soviet gymnast Nellie Kim was her main rival during the Montreal Olympics; Kim became the second gymnast to receive a perfect ten, in her case for her performance on the vault.[29] Comăneci took over the media spotlight from gymnast Olga Korbut, who had been the darling of the 1972 Munich Games.

Comăneci's achievements are pictured in the entrance area of Madison Square Garden in Manhattan, where she is shown presenting her perfect beam exercise.

Comăneci was the first Romanian gymnast to win the Olympic all-around title. She also holds the record as the youngest ever Olympic gymnastics all-around champion. The sport has revised its age-eligibility requirements. Gymnasts must be at least 16 in the same calendar year of the Olympics in order to compete during the Games. When Comăneci competed in 1976, gymnasts had only to be 14 by the first day of the competition.[30] As a result of changes to age eligibility, Comăneci's record cannot be broken.

She was ranked as the BBC Overseas Sports Personality of the Year for 1976[31] and the Associated Press's 1976 "Female Athlete of the Year".[32] Back home in Romania, Comăneci was awarded the Sickle and Hammer Gold Medal for her success,[33] and she was named a Hero of Socialist Labor. She was the youngest Romanian to receive such recognition during the administration of Nicolae Ceaușescu.[14]

"Nadia's Theme"

"Nadia's Theme" refers to an instrumental piece that became linked to Comăneci shortly after the 1976 Olympics. It was part of the musical score of the 1971 film Bless the Beasts and Children, and originally titled "Cotton's Dream". It was also used as the title theme music for the American soap opera The Young and the Restless.

Robert Riger used it in association with slow-motion montages of Comăneci on the television program ABC's Wide World Of Sports. The song became a top-10 single in the fall of 1976, and composers Barry De Vorzon and Perry Botkin, Jr. renamed it as "Nadia's Theme" in Comăneci's honor.[34] Comăneci never performed to "Nadia's Theme", however. Her floor exercise music was a medley of the songs "Yes Sir, That's My Baby" and "Jump in the Line," arranged for piano.[17]

1977–1979

Comăneci successfully defended her European all-around title at the championship competition in 1977. When questions were raised at the competition about the scoring, Ceaușescu ordered the Romanian gymnasts to return home. The team followed orders amid controversy and walked out of the competition during the event finals.[14][35]

Following the 1977 Europeans, the Romanian Gymnastics Federation removed Comăneci from her longtime coaches, the Károlyis, and sent her to Bucharest on August 23 to train at the sports complex. She did not find this change positive, and was struggling with bodily changes as she grew older. Her gymnastics skills suffered, and she was unhappy to the point of losing the desire to live.[14][36] After surviving a suicide attempt,[37] Comăneci competed in the 1978 World Championships in Strasbourg "seven inches taller and a stone and a half [21 pounds] heavier" than she was in the 1976 Olympics.[26] A fall from the uneven bars resulted in a fourth-place finish in the all-around behind Soviets Elena Mukhina, Nellie Kim, and Natalia Shaposhnikova. Comăneci did win the world title on beam, and a silver on vault.[26]

After the 1978 "Worlds", Comăneci was permitted to return to Deva and the Károlyis' school.[38] In 1979, Comăneci won her third consecutive European all-around title, becoming the first gymnast, male or female, to achieve this feat. At the World Championships in Fort Worth that December, Comăneci led the field after the compulsory competition. She was hospitalized before the optional portion of the team competition for blood poisoning, which had resulted from a cut in her wrist from her metal grip buckle. Against doctors' orders, she left the hospital and competed on the beam, where she scored a 9.95. Her performance helped give the Romanians their first team gold medal. After her performance, Comăneci spent several days recovering in All Saints Hospital. She had to undergo a minor surgical procedure for the infected hand, which had developed an abscess.[39][40][41]

1980–1984

1980 Summer Olympics

Comăneci was chosen to participate in the 1980 Summer Olympics in Moscow, then the capital of the Soviet Union. As a result of the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, President Jimmy Carter declared that the United States would boycott the Olympics (several other countries also participated in the boycott, though their reasons varied). According to Comăneci, the Romanian government "touted the 1980 Olympic games as the first all-Communist Games." However, she also noted in her memoir, "in Moscow, we walked into the mouth of a lion's den; it was the Russians' home turf."[42] She won two gold medals, one for the balance beam and one for the floor exercise (in which she tied with Soviet gymnast Nellie Kim, against whom she had also competed in the 1976 Montreal Olympics) and other events. She also won two silver medals, one for the team all-around and one for individual all-around. Controversies arose concerning the scoring in the all-around and floor exercise competitions.[26]

Her coach, Bela Károlyi, protested that she was scored unfairly. His protests were captured on television. According to Comăneci's memoir, the Romanian government was upset about Károlyi's public behavior, feeling that he had humiliated them. Life became very difficult for Károlyi from that point forward.[43]

"Nadia '81"

In 1981, the Gymnastics Federation contacted Comăneci and informed her that she would be part of an official tour of the United States named "Nadia '81" and her coaches Béla and Márta Károlyi would lead the group.[44] During this tour, Comăneci's team shared a bus trip with American gymnasts; it was the third time she had encountered Bart Conner. They had earlier met in 1976. She later remembered thinking, "Conner was cute. He bounced around the bus talking to everyone—he was incredibly friendly and fun."[45]

Her coaches Béla and Márta Károlyi defected on the last day of the tour, along with the Romanian team choreographer Géza Pozsár. Prior to defecting, Károlyi hinted a few times to Comăneci that he might attempt to do so and indirectly asked if she wanted to join him. At that time, she had no interest in defecting, and said she wanted to go home to Romania.[46][47] After the defection of the Károlyis, life changed drastically for Comăneci in Romania, as she could not have predicted. Officials feared that she would also defect. Feeling she was a national asset, they strictly monitored her actions, refusing to allow her to travel outside the country.[48]

1984 Summer Olympics

The government did allow Comăneci to participate in the 1984 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles as part of the Romanian delegation. Although a number of Communist nations boycotted the 1984 Summer Olympics in a tit-for-tat against the U.S.-led boycott of the Olympics in Moscow four years before, Romania chose to participate. Comăneci later wrote in her memoir that many believed Romania went to the Olympics because an agreement had been made with the United States not to accept defectors. But Comăneci did not participate in the Games as a member of the Romanian team; she served as an observer (not a judge). She was able to see Károlyi's new protégé, American gymnast Mary Lou Retton, who dominated the Olympics. The Romanian delegation did not allow her to talk with Károlyi and closely watched her the entire time.[49]

1984–1990

The Romanian government continued to restrict Comăneci from leaving Romania, aside from a few select trips to Moscow and Cuba. She had started thinking about retiring a few years earlier, but her official retirement ceremony took place in Bucharest in 1984. It was attended by the chairman of the International Olympic Committee.[27]

She later wrote in her memoir:

Life took on a new bleakness. I was cut off from making the small amount of extra money that had really made a difference in my family's life. It was also insulting that a normal person in Romania had the chance to travel, whereas I could not…. when my gymnastics career was over, there was no longer any need to keep me happy. I was to do as I was instructed, just as I'd done my entire life…. If Bela hadn't defected, I would still have been watched, but his defection brought a spotlight on my life, and it was blinding. I started to feel like a prisoner.[50]

On the night of November 27, 1989, a few weeks before the Romanian Revolution, Comăneci defected with a group of other Romanians. They were guided by Constantin Panait, a Romanian who later became an American citizen after defecting. Their journey was mostly on foot and at night. They traveled through Communist Hungary and Austria and finally were able to take a plane to the United States.[14][28][51]

1990–present

.jpg)

Comăneci moved to Oklahoma in 1991 to help her friend Bart Conner, another Olympic gold medalist, with his gymnastics school. She lived with the family of Paul Ziert and eventually hired him as her manager.[52] Comăneci and Conner initially were just friends. They were together for four years before they became engaged.[53]

She returned to Romania for their 1996 wedding, which was held in Bucharest. This was after the fall of the Soviet Union and the establishment of an independent Romania; the government welcomed her as a national hero. The wedding was televised live throughout Romania, and the couple's reception was held in the former presidential palace.[28][54]

In 2006, the couple's son Dylan was born.[55][56] Comăneci became a naturalized US citizen in 2001, and is a dual citizen of Romania and the United States.[57]

She was the featured speaker at the 50th annual Independence Day Naturalization Ceremony on July 4, 2012 at Monticello, the first athlete invited to speak in the history of the ceremony.[58] In October 2017, an area in the Olympic Park in Montreal was renamed "Place Nadia Comaneci" in her honor.[59][60]

Leadership roles

Comăneci is a well-known figure in the world of gymnastics; she serves as the honorary president of the Romanian Gymnastics Federation, the honorary president of the Romanian Olympic Committee, the sports ambassador of Romania, and as a member of the International Gymnastics Federation Foundation. She and Conner own the Bart Conner Gymnastics Academy, the Perfect 10 Production Company, and several sports equipment shops, and are the editors of International Gymnast Magazine.

She is also still involved with the Olympic Games. During the 2004 Summer Olympics in Athens, one of her perfect-10 Montreal uneven bars routines was featured in a commercial for Adidas.[61] In addition, both Comăneci and her husband Bart Conner provided television commentary for the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing.[62] A few years later, on July 21, 2012, Comăneci, along with former basketball star John Amaechi, carried the Olympic torch to the roof of the O2 Arena as part of the torch relay for the 2012 Summer Olympics in London.[63] Prior to the 2016 Summer Olympics, in Rio de Janeiro (featuring gymnast Simone Biles), Comăneci appeared in a TIDE advertisement called "The Evolution of Power" with Biles and three-time Olympic gymnast Dominique Dawes.[64][65] She also offered daily analysis of the 2016 games (along with other Olympic champions such as Mark Spitz, Carl Lewis, and Conner), for the late-night show É Campeão, broadcast on Brazil's SporTV.[66]

In addition, Comăneci is highly involved in fundraising for a number of charities. She personally funded the construction and operation of the Nadia Comăneci Children's Clinic in Bucharest that provides low-cost and free medical and social support to Romanian children.[27] In 2003, the Romanian government appointed her as an honorary consul general of Romania to the United States to deal with bilateral relations between the two nations.[67] In addition, both Comăneci and Conner are involved with the Special Olympics.[68][69]

To raise money for charity, Comăneci participated in Donald Trump's reality show, The Celebrity Apprentice, season seven. Comăneci was a member of "The Empresario" team (all women), which lost to "The Hydra" team (all men) in the second episode. Trump responded to this loss by firing Comăneci,[70] thwarting her plan for raising money.[71] Comăneci later commented on her participation in the show, saying, "[she] had great fun. I only did it because it was all for charity."[72]

Honors and awards

- 1975 and 1976: The United Press International Athlete of the Year Award[73]

- 1976: Hero of Socialist Labour[74]

- 1976: Associated Press Athlete of the Year[75]

- 1976: BBC Overseas Sports Personality of the Year[76]

- 1983: The Olympic Order[77]

- 1990: International Women's Sports Hall of Fame[78]

- 1993: International Gymnastics Hall of Fame[79]

- 1998: Marca Leyenda[80]

- 1998: Flo Hyman Award[81]

- 2004: The Olympic Order[82]

- 2016: 2016 Great Immigrant Honoree: Carnegie Corporation of New York[83]

Special skills

Comăneci was known for her clean technique, innovative and difficult original skills, and her stoic, cool demeanor in competition.[17][84][85] On the balance beam, she was the first gymnast to successfully perform an aerial walkover and an aerial cartwheel-back handspring flight series. She is also credited as being the first gymnast to perform a double-twist dismount.[17][84] Her skills on the floor exercise included a tucked double back salto and a double twist.[84]

- Comăneci salto[86]

- Comăneci dismount[87]

Book and films

- Comăneci's 2004 memoir, Letters to a Young Gymnast, is part of the Art of Mentoring series by Basic Books.[88][89]

- Katie Holmes directed a short 2015 documentary for ESPN about Comăneci entitled Eternal Princess that premiered at the Tribeca Film Festival.[90][91]

- In 2016 Arte France produced a Pola Rapaport documentary about Comăneci entitled Nadia Comăneci, la gymnaste et le dictateur (Nadia Comăneci: The Gymnast and the Dictator).[92]

- In 1984, Comăneci was the subject of an unauthorized biopic television film, Nadia.[93] The film was developed without her involvement or permission (although the content was described to her by others). She later stated publicly that the producers "never made contact with me ... I sincerely don't even want to see it, I feel so badly about it. It distorts my life so totally."[93]

See also

References

Citations

- Nadia Comăneci. sports-reference.com

- "Comaneci". Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins. Retrieved May 20, 2019.

- "Comaneci, Nadia" (US) and "Comaneci, Nadia". Oxford Dictionaries UK Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Retrieved May 20, 2019.

- Gymnast Nadia Comăneci Became the Queen of the 1976 Montreal Games when she was Awarded the First Perfect Score.

- The Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia, 6th ed. (2007). "Gymnastics". infoplease.com. Retrieved September 6, 2007.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- "Nadia Comăneci". CNN. July 7, 2008.

- Lafon, Lola. "The Little Communist Who Never Smiled". Serpent's Tail/Profile Books. Retrieved August 27, 2016.

- "Gymnastics legend Nadia Comaneci wants to remind everyone she's from Romania". New York Daily News. August 6, 2016. Retrieved September 4, 2016.

- "Olympic Champion Nadia Comaneci". www.gymn-forum.net.

- http://www.evz.ro/tatal-nadiei-comaneci-a-murit-961238.html

- Comăneci, p. 5.

- "Ştefania Comăneci, mama Nadiei: "Sunt mândră de ea!" | Alte sporturi, Sport". Libertatea. November 11, 2011.

- Comăneci, pp. 94 and 121.

- Fisher, Barbara; Isbister, Jennifer (November 15, 2003). "Nadia Comaneci, a living legend..." Gymnastics Greats. Gymn.ca. Archived from the original on May 28, 2010. Retrieved October 20, 2014.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Comăneci

- Comăneci, pp. 17–19.

- Deford, Frank. "Nadia Awed Ya". Sports Illustrated. August 2, 1976.

- List of competitive results Gymn-Forum

- Comăneci, pp. 27–28.

- "Gymnast Posts Perfect Mark" Robin Herman, New York Times, March 28, 1976.

- Comăneci, p. 53.

- "The Adorable Way This Olympic Couple First Met". Oprah: Where Are They Now?. 2016. Retrieved August 19, 2016.

- "Nadia Comaneci's perfect 10 | Epic Olympic Moments". December 10, 2015 – via YouTube.

- "Biography: COMANECI, Nadia". U.S. Gymnastics Hall of Fame. Retrieved July 17, 2011.

- Cousineau, Phil (2003). The Olympic Odyssey: Rekindling the True Spirit of the Great Games. Quest Books. pp. 160–161. ISBN 0835608336.

- "50 stunning Olympic moments No5: Nadia Comaneci scores a perfect 10". The Guardian. December 14, 2011. Retrieved July 31, 2012.

- Ziert, Paul (2005). "Still A Perfect 10" (PDF). Olympic Review. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 27, 2008. Retrieved June 13, 2013.

- Legends: Nadia Comăneci International Gymnast magazine

- "Nellie Kim (URS)". Archived from the original on February 27, 2011.

- "Within the International Federations" (PDF). Olympic Review. 1980. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 8, 2010. Retrieved June 13, 2013.

- Dodd, Marc (August 1, 2008). "Top Five: Teenage Sensations". Metro. Retrieved January 11, 2009.

- "Associated Press Athletes of the Year". MSN.com. Archived from the original on April 7, 2009.

- "Decretul nr. 250/1976 privind conferirea de distinctii ale Republicii Socialiste Romania unor sportivi, antrenori si activisti din domeniul educatiei fizice si sportului" (in Romanian). Archived from the original on April 11, 2019. Retrieved April 6, 2014.

- "Nadia Comăneci: The Perfect 10" International Olympic Committee (IOC) website

- Comăneci, pp. 61–62.

- Comăneci, pp. 64–68.

- "Comaneci Confirms Suicide Attempt, Magazine Says". Los Angeles Times.

- Comăneci, pp. 68–72.

- "Nadia." The Epistle, (All Saints Episcopal Hospital), January 1980

- Comăneci, pp. 87–91.

- Little Girls in Pretty Boxes. Ryan, Joan. 1995, Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-47790-2.

- Comăneci, p. 98.

- Comăneci, pp. 99–105.

- "Miss Comăneci, 19, Makes Fresh Start". Ira Berkow, New York Times, March 6, 1981

- Comăneci, pp. 111–112.

- Little Girls in Pretty Boxes. Ryan, Joan. 1995, Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-47790-2, p. 201.

- Comăneci, pp. 113–120.

- Comăneci, pp. 120–125.

- Comăneci, pp. 125–6.

- Comăneci, p. 121.

- Comăneci, pp. 137–148.

- Comăneci, pp. 160–162.

- Comăneci, pp. 162–164.

- "Nadia Tumbles over Wedding" Cincinnati Post, April 6, 1996

- "Nadia Comăneci, Bart Conner Have a Boy, People, June 6, 2006

- "Former Gymnasts Nadia Comăneci and Bart Conner Baptized Their First Child, Dylan Paul" Archived July 26, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, Catalina Iancu, Jurnalul National, August 28, 2006

- "Nadia Comaneci on Winning Carnegie's Great Immigrant Award". Oprah.com. July 14, 2016. Retrieved March 20, 2018.

- "Olympic champion Nadia Comăneci to be featured July 4 speaker at Monticello". monticello.org. May 11, 2012. Retrieved April 21, 2013.

- Amadon, Brett (October 4, 2017). "Nadia Comaneci honored with public space next to Montreal's Olympic Stadium". Excelle Sports. Archived from the original on October 17, 2017. Retrieved October 12, 2017.

- "Montreal Olympic Park unveils plaza honouring gymnast Nadia Comaneci". Montreal Gazette. October 4, 2017. Retrieved October 12, 2017.

- "2004 Athens Games: Advertising". SFGate. August 12, 2004. Retrieved April 21, 2013.

- Roenigk, Alyssa (August 17, 2008). "The First Family of Gymnastics". ESPN The Magazine. Retrieved August 21, 2008.

- "London 2012 Olympics: The torch begins its journey across London". The Daily Telegraph. July 21, 2012. Retrieved March 15, 2013.

- "Dominique Dawes Predicts How Many Golds for Simone Biles?". June 30, 2016.

- "Olympic Gymnasts Simone Biles, Dominique Dawes, And Nadia Comaneci Partner In 'The Evolution of Power' Video". HuffPost. July 14, 2016.

- Staff, S. V. G. "Rio 2016: Globosat's SporTV Captivates Olympic Fans in Brazil". Sports Video Group.

- Honorary Consulates of Romania in the US Retrieved July 31, 2012.

- "Nadia Comaneci, Global Ambassador". Archived from the original on December 9, 2014. Retrieved October 16, 2016.

- "On Mats, Bars and Boards, Bart Conner and Nadia Comaneci Lead by Example". Archived from the original on September 11, 2017. Retrieved October 16, 2016.

- "Celebrity Apprentice: Ivanka Trump vs. Gene Simmons". PEOPLE.com.

- Oct 20, foxsports; ET, 2016 at 4:59p. "Sports stars on reality TV". FOX Sports.

- "Nadia travels from "10" to Trump". January 10, 2008.

- Gerry, Brown; Morrison, Michael, eds. (2003). ESPN Information Please Sports Almanac. New York City: ESPN Books and Hyperion (joint). ISBN 0-7868-8715-X.

- Laszlo, Erika (November 29, 1989). "Comaneci, darling of '76 Olympics, defects". United Press International. Retrieved July 16, 2018.

- "Simone Biles chosen as AP's Female Athlete of the Year". CBS News. December 26, 2016. Retrieved July 16, 2018.

- Dodd, Marc (August 1, 2008). "Top Five: Teenage Sensations". Metro. Retrieved January 11, 2009.

- "Olympic Awards presented at the 87th IOC Session", Olympic Review '84 (PDF), International Olympic Committee, retrieved May 15, 2015 – via LA84 Foundation

- "International Women's Sports Hall of Fame". Women's Sports Foundation. Archived from the original on March 5, 2017. Retrieved July 16, 2018.

- "Inductees". International Gymnastics Hall of Fame. Retrieved July 16, 2018.

- "MARCA Leyenda". Marca. Archived from the original on July 17, 2018. Retrieved July 16, 2018.

- Leibowitz, Elissa (February 6, 1998). "Comaneci Vaults Back Into the Spotlight; Olympic Gymnast Receives Women's Sports Foundation Award". The Washington Post. p. C2. Retrieved March 9, 2011.(subscription required)

- "A new trophy for Nadia Comaneci". International Olympic Committee. March 29, 2004. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved December 19, 2011.

- 2016 Great Immigrants Honorees: The Pride of America

- "A Great Leap Backward" Anita Verschoth, Sports Illustrated, April 12, 1976

- "The Games: Up in the Air" Time, August 2, 1976

- Comăneci, p. 1.

- Comăneci, p. 15.

- Comăneci

- Letters to a Young Gymnast. basicbooks.com

- "Eternal Princess". Archived from the original on September 16, 2016. Retrieved August 19, 2016.

- "Short Film Eternal Princess, Directed by Katie Holmes, Debuts on espnW". Archived from the original on September 10, 2016. Retrieved August 19, 2016.

- "Nadia Comaneci, la gymnaste et le dictateur". ARTE Boutique - Films et séries en VOD, DVD, location VOD, documentaires, spectacles, Blu-ray, livres et BD.

- Lindsey, Robert (July 29, 1984). "Nadia Comaneci Still Glows as Images of 1976 Recede". New York Times. Retrieved September 4, 2016.

Cited sources

- Comăneci, Nadia (2004). Letters to a Young Gymnast. The Art of Mentoring. Basic Books. ISBN 0-465-01276-0.

Further reading

- Kerr, Roslyn. "The Impact of Nadia Comaneci on the Sport of Women's Artistic Gymnastics." Sporting Traditions, Australian Society for Sports History. November 2006:87–102.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Nadia Comăneci. |

- Official website

- Nadia Comăneci on IMDb

- Voices of Oklahoma interview with Bart Conner. First person interview conducted on February 28, 2013, with Bart Conner, husband of Nadia Comăneci.

Video clips:

- Nadia Comăneci makes history at the Montreal 1976 Olympics – The Olympic Channel, 2010

- Nadia Comăneci – First Olympics Perfect 10 (Uneven Bars)- Montreal 1976 Olympics – The Olympic Channel, 2015

- Nadia Comăneci – Selections from all of her routines – Montreal 1976 Olympics (overview) – The Olympic Channel, 2012

- The Adorable Way This Olympic Couple First Met | Where Are They Now | Oprah Winfrey Network – Oprah Winfrey Network (U.S. TV channel), 2016

- Nadia Comaneci & Bart Conner Commentate on Their Perfect Olympic Routines | Take the Mic – The Olympic Channel, 2016

- Nadia Comaneci and Bart Conner, 11 Olympic Medals in this Olympic Family – The Olympic Channel, 2016

| Awards and achievements | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Irena Szewińska |

United Press International Athlete of the Year 1975, 1976 |

Succeeded by Rosemarie Ackermann |

| Preceded by Arthur Ashe |

BBC Overseas Sports Personality of the Year 1976 |

Succeeded by Niki Lauda |

| Preceded by Billie Jean King |

Flo Hyman Memorial Award 1998 |

Succeeded by Bonnie Blair |