Balance beam

The balance beam is a rectangular artistic gymnastics apparatus, as well as the event performed using the apparatus. Both the apparatus and the event are sometimes simply referred to as "beam". The English abbreviation for the event in gymnastics scoring is BB. The beam is a small, thin beam which is typically raised from the floor on a leg or stand at both ends. The balance beam is only performed by female gymnasts. Beams are usually covered with leatherlike material, and are only 4 inches wide.

Balance beams used in international gymnastics competitions must conform to the guidelines and specifications set forth by the International Gymnastics Federation Apparatus Norms brochure. Several companies manufacture and sell beams, including AAI (USA), Janssen Fritsen (Europe) and Acromat (Australia). Most gymnastics schools purchase and use balance beams that meet the FIG's standards, but some may also use beams with carpeted surfaces for practice situations. While learning new skills, gymnasts often work on floor beams that have the same dimensions and surface of regulation apparatus, but are set a very short distance from or on the ground. They may also work on medium beams, mini beams, road beams, or even lines on a mat.

Originally, the beam surface was plain polished wood.[1] In earlier years, some gymnasts competed on a beam made of basketball-like material. However, this type of beam was eventually banned due to its extreme slipperiness. Since the 1980s, beams have been covered in leather or suede. In addition, they are now also sprung to accommodate the stress of high-difficulty tumbling and turns and poses.[2]

Dimensions

Measurements of the apparatus are published by the Fédération Internationale de Gymnastique (FIG) in the Apparatus Norms brochure.

- Height: 125 centimetres (4.10 ft)[3]

- Length: 500 centimetres (16 ft)[3]

- Width: 10 centimetres (3.9 in)[3]

Evolutions

In the early days of women's artistic gymnastics, beam was based more in dance than in tumbling. Routines even at the elite level were composed with combinations of leaps, dance poses, handstands, rolls and walkovers. In the 1960s, the most difficult acrobatic skill performed by the average Olympic gymnast was a back handspring.

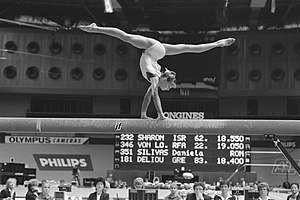

Balance beam difficulty began to increase dramatically in the 1970s. Olga Korbut and Nadia Comăneci pioneered advanced tumbling combinations and aerial skills on beam; other athletes and coaches began to follow suit. The change was also facilitated by the transition from wooden beams to safer, less slippery models with suede-covered surfaces. By the mid-1980s, top gymnasts routinely performed flight series and multiple aerial elements on beam.

Today, balance beam routines still consist of a mixture of acrobatic skills, dance elements, leaps and poses, but with significantly greater difficulty. It is also an individual medal competition in the Olympics.

International level routines

For detailed information on score tabulation, please see the Code of Points article.

A beam routine must consist of:[4]

- A connection of two dance elements, one a leap, jump, or hop with legs in 180 degree split

- A full turn on one foot

- One series of two acrobatic skills

- Acrobatic elements in different directions (forward/sideward and backward)

- A dismount

The gymnast may mount the beam using a springboard or from the mat; however the mount must come from the Code of Points.[4] The routines can last up to 90 seconds.[4]

Scoring and rules

Several aspects of the performance determine the gymnast's final mark. All elements in the routine, as well as all errors, are noted by the judges.

Deductions are taken for all errors made while on the beam, including lapses in control, balance checks (i.e., wobbling or stumbling to maintain balance), poor technique and execution, and failure to fulfill the required Code of Points elements. Falls automatically incur a deduction depending on the level the gymnast is on.[5]

Apparatus specific rules

The gymnast may compete barefoot or wear special beam shoes if she so chooses.[6] She may also chalk her hands and/or feet for added stability on the apparatus. Small markings may also be placed on the beam.[6]

Once the exercise has started, the gymnast's coach may not spot her or interfere in any way. The only time the gymnast may be accompanied on the podium is in the case of a mount involving a springboard. In this instance, the coach may quickly step in to remove the springboard from the area.[7]

In the event of a fall, once the athlete is on her feet, she has 10 seconds to remount the beam and continue the routine.[4] If she does not return to the beam within this time limit, she is not permitted to continue.[4]

Under FIG rules, the maximum allowed time for a balance beam routine is 1:30 minutes.[4] The routine is timed on the scoreboard timer, which is visible to both the gymnast and judges. In addition, a warning tone or bell is sounded 1:20 into the exercise.[4] If the gymnast has not left the beam by 1:30, another bell is sounded, and a score deduction is incurred which is 0.1.

References

- "History of Balance Beam". Archived from the original on 2009-06-18. Retrieved 2009-10-04.

- "Apparatus Norms". FIG. p. II/50. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-12-19. Retrieved 2009-10-04.

- "Apparatus Norms". FIG. p. II/51. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-12-19. Retrieved 2009-10-04.

- "WAG Code of Points 2009-2012". FIG. p. 26. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 12, 2009. Retrieved 2009-10-02.

- "WAG Code of Points 2009-2012". FIG. p. 15. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-12-19. Retrieved 2009-10-02.

- "WAG Code of Points 2009-2012". FIG. p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-12-19. Retrieved 2009-10-04.

- "WAG Code of Points 2009-2012". FIG. p. 3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-12-19. Retrieved 2009-10-02.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Balance beam. |