Minoan art

Minoan art is the art produced by the Minoan civilization from about 2600 to 1100 BC.[1]

The largest collection of Minoan art is in the museum at Heraklion, near Knossos, on the northern coast of Crete. Minoan art and other remnants of material culture, especially the sequence of ceramic styles, have been used by archaeologists to define the three phases of Minoan culture (EM, MM, LM).

Since wood and textiles have decomposed, the best-preserved (and most instructive) surviving examples of Minoan art are its pottery, palace architecture (with frescos which include landscapes), stone carvings and intricately-carved seal stones.

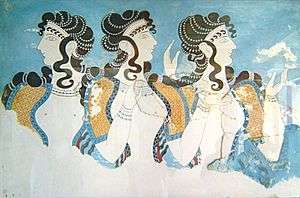

Painting

Frescoes were the stereotypical type of Art that depicted natural movements.[2] Several frescoes at Knossos and Santorini survive. Arthur Evans hired Swiss artist Emile Gilliéron and his son, Emile, as the chief fresco restorers at Knossos.[3] Spyridon Marinatos unearthed the ancient site at Santorini, which included frescoes which make it the second-most famous Minoan site.

In contrast to Egyptian frescoes, Crete had true frescoes. Probably the most famous fresco is the bull-leaping fresco.[4] They include many depictions of people, with sexes distinguished by color; the men's skin is reddish-brown, and the women's white.[5]

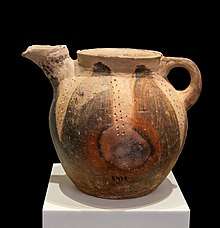

Pottery

Many different styles of potted wares and techniques of production are observable throughout the history of Crete. Early Minoan ceramics were characterized by patterns of spirals, triangles, curved lines, crosses, fish bones, and beak-spouts. However, while many of the artistic motifs are similar in the Early Minoan period, there are many differences that appear in the reproduction of these techniques through out the island which represent a variety of shifts in taste as well as in power structures.[6] During the Middle Minoan period, naturalistic designs (such as fish, squid, birds and lilies) were common. In the Late Minoan period, flowers and animals were still characteristic but more variety existed.

EM I Wares

One of the earliest styles in EM I was the Coarse Dark Burnished class. The dark burnished class most closely mimics the techniques of the Neolithic era. After new techniques allowed for the development of new styles of pottery in the early bronze age, Coarse Dark Burnished class remained in production, and while most wares from the Coarse Dark Burnished class are generally less extravagant than other styles that utilize the technological developments that emerged during EM I, some examples of intricate pieces exist.[7] This may suggest that there was a desire within the communities who produced Coarse Dark Burnished ware to separate themselves from the communities who produced wares with the new techniques.

The Aghious Onouphrios and the Lebena classes were two of the most widespread styles of pottery that used techniques of which there are no antecedent examples.[8] Both techniques utilized a variety of new techniques, for example the selection and handling of materials, the firing process, sapping and ornamentation. Both styles used fine patterns of lines to ornament the vessels. In the case of Aghious Onouphrios, vessel had a white backing and were painted with red lining. Conversely, in the case of the Lebena style white lines were painted above a red background.

Another EM I class was Pirgos ware. The style may have been imported,[9] and perhaps mimics wood. Pirgos wares utilize a combination of old and new techniques. Pirgos wares are a subdivision of the Fine Dark Burnished class that have characteristic burnished patterns. The patterning is likely due to an inability to effectively paint the styles' dark background.[10]

These three classes of EM I pottery adequately reveal the diversity of techniques that emerged during the period. The Coarse Dark Burnished class continued to use techniques that were already in use, the Aghious Onouphrios and Lebana class used completely new techniques, and the Fine Dark Burnished class used a combination of old and new techniques. However a variety of other EM I wares have been discovered, e.g. the Scored, Red to Brown Monochrome, and the Cycladic classes. Additionally, all of the classes utilized different shapes of pottery.

EM II-III Wares

In the first phase of Early Minoan, the Aghious Onouphrios ware is most common. Vasiliki ware is found in East Crete during the EM IIA period, but it is in the next period, EM IIB, that it becomes the dominant form among the fine wares throughout eastern and southern Crete.[11] Both styles contain a reddish wash.[12] However, Vasiliki ware has a unique mottled finish that distinguishes it from the EM I styles pottery. At times this mottled finish is deliberate and controlled and at others it seems uncontrolled. Like EM I, a variety classifications of Pottery emerged during this period. Koumasa ware is a development of Aghious and Lebana styles of pottery and was prominent in EM IIA, prior to Vasiliki wares' increased popularity. Additionally, gray wares continued to be produced throughout EMII and a Fine Gray class of wares emerges. The Fine Gray class follows the trend of the majority of EM II pottery and is a remarkably higher quality than previous wares.[13]

EM III, the final phase of the early Minoan period, is dominated by the White-On-Dark class. Some locations have been discovered that housed over 90% White-On-Dark ware. The class utilizes complex spirals and other ornate patterning that have naturalistic appearances. But not all producers of these wares used these patterns at the same time. Rather, the motifs caught hold over an extended period of time. These developments set the mood for the new classes that would emerge in the Middle Minoan period.

EM II-III are marked by a refining of the techniques and styles of pottery that emerged and evolved during EM I and these refinements would ultimately set the themes for the later works of Minoan and Mycenaean pottery.

MM Wares

Pottery became more common with the building of the palaces and the potter's wheel.[14] Kamares ware is most typical of this period. The MM period was dominated by the development of monumental palaces. These places centralized the production of potted wares. This centralization led artists to become more aware of what other craftsmen were producing and wares became more homogeneous in shapes in styles.[15]

While the pottery became more homogeneous in style during MM, the wares did not become any less ornate. Indeed, during the MM period the most elaborate decorations of any previous period emerge. These designs were likely inspired by the fresco that emerged during the palatial era.[16] The Kamares ware that came to dominated the period utilized flower, fish, and other naturalistic ornamentation, and although the White-On-Gray class had begun to articulate prototypes of these patterns in EM III, the new decorative techniques of this period have no parallel.

LM Wares

The palace style of the region around Knossos is characterized by geometric simplicity and monochromatic painting. LM wares continued the extravagance of decoration that became popular during the MM period. The patterns and images that were used to decorate pottery became more detailed and more varied. The Floral Style, Marine style, Abstract Geometric and the Alternating styles of decoration were prominent themes of this era. Additionally, potted wares that depicted animals, e.g. the head's of bulls, became popular during LM. These decorative pieces were painted with the popular patterns of the time creating some of the most elaborate of all Minoan potted goods.[17]

LM pottery achieved the full articulation of the themes and techniques that had existed since the neolithic era. Yet, this articulation was not the product of linear development. Rather, it was produced through the dynamic exchange of ideas and techniques and will to break away from, as well as to conform to, previous molds of production. Late Minoan art in turn influenced that of Mycenae. Minoan knowledge of the sea was continued by the Mycenaeans in their frequent use of marine forms as artistic motifs. The so marine style, perhaps inspired by frescoes, has the entire surface of a pot covered with sea creatures, octopus, fish and dolphins, against a background of rocks, seaweed and sponges.

Jewelry

The Minoans created elaborate metalwork with imported gold and copper.[18] Bead necklaces, bracelets and hair ornaments appear in the frescoes,[19] and many labrys pins survive. The Minoans apparently mastered faience and granulation, as indicated by a gold bee pendant. Minoan metalworking included intense, precise temperature, to bond gold to itself without melting it.

Metal vessels

Metal vessels were produced in Crete from at least as early as EM II (c. 2500) in the Prepalatial period through to LM IA (c. 1450) in the Postpalatial period and perhaps as late as LM IIIB/C (c. 1200),[20] although it is likely that many of the vessels from these later periods were heirlooms from earlier periods.[21] The earliest were probably made exclusively from precious metals, but from the Protopalatial period (MM IB – MM IIA) they were also produced in arsenical bronze and, subsequently, tin bronze.[22] The archaeological record suggests that mostly cup-type forms were created in precious metals,[23] but the corpus of bronze vessels was diverse, including cauldrons, pans, hydrias, bowls, pitchers, basins, cups, ladles and lamps.[24] The Minoan metal vessel tradition influenced that of the Mycenaean culture on mainland Greece, and they are often regarded as the same tradition.[25] Many precious metal vessels found on mainland Greece exhibit Minoan characteristics, and it is thought that these were either imported from Crete or made on the mainland by Minoan metalsmiths working for Mycenaean patrons or by Mycenaean smiths who had trained under Minoan masters.[26]

It is not clear what the functions of the vessels were, but scholars have proposed some possibilities.[27] Cup-types and bowls were probably for drinking and hydrias and pitchers for pouring liquids, while cauldrons and pans may have been used to prepare food, and other specialised forms such as sieves, lamps and braziers had more specific functions.[28] Several scholars have suggested that metal vessels played an important role in ritual drinking ceremonies and communal feasting, where the use of the valuable bronze and precious metal vessels by elites signified their high status, power and superiority over lower-status participants who used ceramic vessels.[29][30][31] During later periods, when Mycenaean peoples settled in Crete, metal vessels were often interred as grave goods.[32] In this type of conspicuous burial, they may have symbolised the wealth and status of the individual by alluding to their ability to sponsor feasts, and it is possible that sets of vessels interred in graves were used for funerary feasting prior to the burial itself.[33][34] Metal vessels may also have been used for political gift exchange, where the value of the gift reflects the wealth or status of the giver and the perceived importance of the recipient. This could explain the presence of Minoan vessels in the Mycenaean shaft graves of Grave Circle A and their depiction in an Egyptian Eighteenth Dynasty tomb at Thebes.[35]

Extant vessels from the Prepalatial to Neopalatial periods are almost exclusively from destruction contexts; that is, they were buried by the remains of buildings which were destroyed by natural or man-made disasters. By contrast, vessels remaining from Final Palace and Postpalatial periods, after Mycenaean settlement in Crete, are mostly from burial contexts.[32] This reflects, to a large extent, the change in burial practices during this time.[36] The significance is that vessels from the earlier settlement destruction contexts were accidentally deposited and may therefore reflect a random selection of the types of vessels in circulation at the time, but those from the later burial contexts were deliberately chosen and deposited, possibly for specific symbolic reasons which we are not aware of. This means that the extant vessels from this period are probably less representative of the varieties of vessel types that were in circulation at the time.[37]

Minoan metal vessels were generally manufactured by raising sheet metal, although some vessels may have been cast by the lost wax technique.[38] Research suggests that Minoan metalsmiths mostly used stone hammers without handles and wooden metalsmithing stakes to raise vessels.[39] Many vessels have legs, handles, rims and decorative elements which were cast separately and riveted onto the raised vessel forms. Separate pieces of raised sheet were also riveted together to form larger vessels. Some vessels were decorated by various means. Cast handles and rims of some bronze vessels have decorative motifs in relief on their surfaces,[40][41][42] and the walls of some vessels were worked in repoussé and chasing. Precious metal vessels were ornamented with repoussé, ornamental rivets, gilding, bi-metallic overlays and inlaying of other precious metals or a niello-type substance.[43] Motifs on metal vessels correlate to those found on other Minoan art forms such as pottery, frescoes, stone seals and jewellery, including spirals, arcades, flora and fauna, including bulls, birds and marine life. Minoan smiths probably also produced animal-head rhyta in metal, as they did in stone and ceramic, but none in metal are extant from Crete.[44] The iconographical significance of these motifs is largely unknown, although some scholars have identified general themes from the contexts in which they were used.[45][46]

Notes

- Sakoulas, Thomas. "Minoan Art". ancient-greece.org. Retrieved 2017-10-01.

- Sakoulas, Thomas. "Minoan Art". ancient-greece.org. Retrieved 2017-10-02.

- "Historic Images of the Greek Bronze Age".

- Smith, Gregory A. (2014-08-08). The Traveler's Guide to Greek Archaeology: Getting the Most from your Mediterranean Trip. ISBN 978-1-4602-4789-1.

- Hood, Sinclair (1985). "The Primitive Aspects of Minoan Artistic Convention". Bulletin de Correspondence Héllenique. Suppl. 11: 21–26.

- Castleden, Rodney (1993). Minoans: Life in Bronze Age. Routledge. p. 106.

- Betancourt, Philip (2009). The Bronze Age Begins. INSTAP. pp. 44–47.

- Betancourt, Philip (2009). The Bronze Age Begins. INSTAP. p. 43.

- Castleden, Rodney (2002-01-04). Minoans: Life in Bronze Age Crete. ISBN 978-1-134-88063-8.

- Betancourt, Philip (2009). The Bronze Age Begins. INSTAP. p. 56.

- Minoan settlement of Vasiliki minoancrete.com

- Pedley, pp. 36–37

- Betancourt, Philip (1985). The History of Minoan Pottery. Princeton University Press. pp. 35–38.

- Pedley, p. 52

- Betancourt, Philip (1985). The History of Minoan Pottery. Princeton University Press. p. 64.

- Higgins, Reynolds (1985). Minoan and Mycenaean Art. Thames and Hudson. p. 103.

- Betancourt, Philip (1985). The History of Minoan Pottery. Princeton University Press. pp. 144–149.

- Thomas Sakoulas. "Minoan Art".

- "Greek Jewelry – AJU".

- Hemingway, Séan (1 January 1996). "Minoan Metalworking in the Postpalatial Period: A Deposit of Metallurgical Debris from Palaikastro". The Annual of the British School at Athens. 91: 213–252. doi:10.1017/S0068245400016488. JSTOR 30102549.

- Rehak, Paul (1997). "Aegean Art Before and After the LM IB Cretan Destructions". In Laffineur, Robert; Betancourt, Philip P. (eds.). TEXNH. Craftsmen, Craftswomen and Craftsmanship in the Aegean Bronze Age / Artisanat et artisans en Égée à l'âge du Bronze: Proceedings of the 6th International Aegean Conference / 6e Rencontre égéenne internationale, Philadelphia, Temple University, 18-21 April 1996. Liège: Université de Liège, Histoire de l'art et archéologie de la Grèce antique. p. 145. ISBN 978-1-935488-11-8.

- Clarke, Christina F. (2013). The Manufacture of Minoan Metal Vessels: Theory and Practice. Uppsala: Åströms Förlag. p. 1. ISBN 978-91-7081-249-1.

- Davis, Ellen N. (1977). The Vapheio Cups and Aegean Gold and Silver Ware. New York: Garland Pub. ISBN 978-0-8240-2681-3.

- Matthäus, Hartmut (1980). Die Bronzegefässe der kretisch-mykenischen Kultur. München: C.H. Beck. ISBN 978-3-406-04002-3.

- Catling, Hector W. (1964). Cypriot Bronzework in the Mycenaean World. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 187.

- Davis 1977, pp. 328–352

- This paragraph is paraphrased from Clarke 2013, pp. 35–36

- Matthäus 1980, pp. 343–344

- Sherratt, Andrew; Taylor, Timothy (1989). "Metal Vessels in Bronze Age Europe and the Context of Vulchetrun". In Best, Jan Gijsbert Pieter; De Vries, Manny M. W. (eds.). Thracians and Mycenaeans: Proceedings of the Fourth International Congress of Thracology, Rotterdam, 24-26 September 1984. Leiden: Brill Archive. pp. 106–107. ISBN 9789004088641.

- Wright, James C. (2004). "A Survey of Evidence for Feasting in Mycenaean Society". Hesperia. 73 (2): 137–145. JSTOR 4134891.

- Soles, Jeffrey S. (2008). "Period IV: The Mycenaean Settlement and Cemetery: The Sites". Mochlos IIA: Period IV: The Mycenaean Settlement and Cemetery: The Sites. 23. INSTAP Academic Press. pp. 143, 155. ISBN 978-1-931534-23-9. JSTOR j.ctt3fgw67.

- Matthäus 1980, pp. 61–62

- Baboula, Evanthia (2000). "'Buried' Metals in Late Minoan Inheritance Customs". In Pare, C. F. E. (ed.). Metals Make the World Go Round: The Supply and Circulation of Metals in Bronze Age Europe : Proceedings of a Conference Held at the University of Birmingham in June 1997. Oxford: Oxbow. p. 74. ISBN 978-1-84217-019-9.

- Wright 2004, p. 147

- Clarke 2013, p. 36

- Preston, Laura (2008). "Late Minoan II to IIIB Crete". In Shelmerdine, Cynthia W. (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to the Aegean Bronze Age. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 311. doi:10.1017/CCOL9780521814447.014. ISBN 978-1-139-00189-2.

- Matthäus 1980, p. 61

- Matthäus 1980, pp. 326–327

- Clarke, Christina (2014). "Minoan Metal Vessel Manufacture: Reconstructing Techniques and Technology with Experimental Archaeology" (PDF). In Scott, Rebecca B.; Braekmans, Dennis; Carremans, Mike; Degryse, Patrick (eds.). 39th International Symposium on Archaeometry: 28 May – 1 June 2012 Leuven, Belgium. Leuven: Centre for Archaeological Sciences, KU Leuven. pp. 81–85.

- Catling 1964, p. 174

- Matthäus 1980, p. 329

- Evely, R.D.G. (2000). Minoan Crafts: Tools and Techniques: An Introduction. Jonsered: Paul Åström. p. 382. ISBN 9789170811555.

- Davis 1977, pp. 331–332

- Davis 1977, pp. 189–190

- Furumark, Arne (1972). Mycenaean Pottery I: Analysis and Classification (Reprint 1941 ed.). Stockholm: Åström. ISBN 9185086045.

- Crowley, Janice L. (1989). The Aegean and the East: An Investigation into the Transference of Artistic Motifs between the Aegean, Egypt, and the Near East in the Bronze Age. Göteborg: Åström. ISBN 9789186098551.

References

- Baboula, Evanthia (2000). "'Buried' Metals in Late Minoan Inheritance Customs". In Pare, C. F. E. (ed.). Metals Make the World Go Round: The Supply and Circulation of Metals in Bronze Age Europe : Proceedings of a Conference Held at the University of Birmingham in June 1997. Oxford: Oxbow. pp. 70–81. ISBN 978-1-84217-019-9.

- Catling, Hector W. (1964). Cypriot Bronzework in the Mycenaean World. Oxford: Clarendon Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Clarke, Christina F. (2013). The Manufacture of Minoan Metal Vessels: Theory and Practice. Uppsala: Åströms Förlag. ISBN 978-91-7081-249-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Clarke, Christina (2014). "Minoan Metal Vessel Manufacture: Reconstructing Techniques and Technology with Experimental Archaeology" (PDF). In Scott, Rebecca B.; Braekmans, Dennis; Carremans, Mike; Degryse, Patrick (eds.). 39th International Symposium on Archaeometry: 28 May – 1 June 2012 Leuven, Belgium. Leuven: Centre for Archaeological Sciences, KU Leuven. pp. 81–85.

- Crowley, Janice L. (1989). The Aegean and the East: An Investigation into the Transference of Artistic Motifs between the Aegean, Egypt, and the Near East in the Bronze Age. Göteborg: Åström. ISBN 9789186098551.

- Davis, Ellen N. (1977). The Vapheio Cups and Aegean Gold and Silver Ware. New York: Garland Pub. ISBN 978-0-8240-2681-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Furumark, Arne (1972). Mycenaean Pottery I: Analysis and Classification (Reprint 1941 ed.). Stockholm: Åström. ISBN 9185086045.

- Hemingway, Séan (1 January 1996). "Minoan Metalworking in the Postpalatial Period: A Deposit of Metallurgical Debris from Palaikastro". The Annual of the British School at Athens. 91: 213–252. doi:10.1017/S0068245400016488. JSTOR 30102549.</ref>

- Matthäus, Hartmut (1980). Die Bronzegefässe der kretisch-mykenischen Kultur. München: C.H. Beck. ISBN 978-3-406-04002-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pedley, John Griffiths (2012). Greek Art and Archaeology. ISBN 978-0-205-00133-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)*Preston, Laura (2008). "Late Minoan II to IIIB Crete". In Shelmerdine, Cynthia W. (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to the Aegean Bronze Age. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 310–326. doi:10.1017/CCOL9780521814447.014. ISBN 978-1-139-00189-2.

- Rehak, Paul (1997). "Aegean Art Before and After the LM IB Cretan Destructions". In Laffineur, Robert; Betancourt, Philip P. (eds.). TEXNH. Craftsmen, Craftswomen and Craftsmanship in the Aegean Bronze Age / Artisanat et artisans en Égée à l'âge du Bronze: Proceedings of the 6th International Aegean Conference / 6e Rencontre égéenne internationale, Philadelphia, Temple University, 18-21 April 1996. Liège: Université de Liège, Histoire de l'art et archéologie de la Grèce antique. p. 145. ISBN 978-1-935488-11-8.

- Sherratt, Andrew; Taylor, Timothy (1989). "Metal Vessels in Bronze Age Europe and the Context of Vulchetrun". In Best, Jan Gijsbert Pieter; De Vries, Manny M. W. (eds.). Thracians and Mycenaeans: Proceedings of the Fourth International Congress of Thracology, Rotterdam, 24-26 September 1984. Leiden: Brill Archive. pp. 106–134. ISBN 9789004088641.

- Soles, Jeffrey S. (2008). "Period IV: The Mycenaean Settlement and Cemetery: The Sites". Mochlos IIA: Period IV: The Mycenaean Settlement and Cemetery: The Sites. 23. INSTAP Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-931534-23-9. JSTOR j.ctt3fgw67.

- Wright, James C. (2004). "A Survey of Evidence for Feasting in Mycenaean Society". Hesperia. 73 (2): 133–178. doi:10.2972/hesp.2004.73.2.133. JSTOR 4134891.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)